Marsden Hartley

Marsden Hartley (January 4, 1877 – September 2, 1943) was an American Modernist painter, poet, and essayist. Hartley developed his painting abilities by observing Cubist artists in Paris and Berlin.[1]

Marsden Hartley | |

|---|---|

Marsden Hartley in 1939 | |

| Born | Edmund Hartley January 4, 1877 Lewiston, Maine, USA |

| Died | September 2, 1943 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Cleveland Institute of Art, National Academy of Design |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | American Modernism |

Early Life and Education

Hartley was born in Lewiston, Maine,[2] where his English parents had settled. He was the youngest of nine children.[3] His mother died when he was eight, and his father remarried four years later to Martha Marsden.[4] His birth name was Edmund Hartley; he later assumed Marsden as his first name when he was in his early 20s.[3] A few years after his mother's death when Hartley was 14, his family moved to Ohio, leaving him behind in Maine to work in a shoe factory for a year.[5] These bleak occurrences led Hartley to recall his New England childhood as a time of painful loneliness, so much so that in a letter to Alfred Stieglitz, he once described the New England accent as "a sad recollection [that] rushed into my very flesh like sharpened knives."[6]

After he joined his family in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1892, Hartley began his art training at the Cleveland School of Art, where he held a scholarship.[2][7]

In 1898, at age 22, Hartley moved to New York City to study painting at the New York School of Art under William Merritt Chase, and then attended the National Academy of Design.[2] Hartley was a great admirer of Albert Pinkham Ryder and visited his studio in Greenwich Village as often as possible. His friendship with Ryder, in addition to the writings of Walt Whitman and American transcendentalists Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, inspired Hartley to view art as a spiritual quest.[2]

Maturation and New York Exhibitions

Hartley moved to an abandoned farm near Lovell, Maine, in 1908.[2] He considered the paintings he produced there his first mature works, and they also impressed New York photographer and art promoter Alfred Stieglitz.[2] Hartley had his first solo exhibition at Stieglitz's 291 in 1909,[2] and exhibited his work there again in 1912. Stieglitz also provided Hartley's introduction to European modernist painters, of whom Cézanne, Picasso, and Matisse would prove the most influential upon him.[2]

Hartley in Europe

.jpg)

Hartley first traveled to Europe for the first time in April 1912, and he became acquainted with Gertrude Stein's circle of avante-garde writers and artists in Paris.[2] Stein, along with Hart Crane and Sherwood Anderson, encouraged Hartley to write as well as paint.[3]

In a letter to Alfred Stieglitz, Hartley explains his disenchantment of living abroad in Paris. A single year has passed since he began living overseas. "Like every other human being I have longings which through tricks of circumstances have been left unsatisfied... and the pain grows stronger instead of less and it leaves one nothing but the role of spectator in life watching life go by-having no part of it but that of spectator."[8] Hartley wanted to live within the noiseless countryside and an invigorating city.[9]

German Sympathies

In April 1913 Hartley relocated to Berlin, the capital of the German Empire, where he continued to paint and befriended the painters Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc.[2] He also collected Bavarian folk art.[10] His work during this period was a combination of abstraction and German Expressionism, fueled by his personal brand of mysticism.[2] Many of Hartley's Berlin paintings were further inspired by the German military pageantry then on display, though his view of this subject changed after the outbreak of World War I, once war was no longer "a romantic but a real reality."[10] The earliest of his Berlin paintings were shown in the landmark 1913 Armory Show in New York.[4]

In Berlin, Hartley developed a close relationship with a Prussian lieutenant, Karl von Freyburg, who was the cousin of Hartley's friend Arnold Ronnebeck. References to Freyburg were a recurring motif in Hartley's work,[10] most notably in Portrait of a German Officer (1914).[11] Freyburg's subsequent death during the war hit Hartley hard, and he afterward idealized their relationship.[10] Many scholars interpreted his work regarding Freyburg as embodying his homosexual feelings for him.[4] Hartley lived in Berlin until December 1915.[12]

Hartley returned to the U.S. from Berlin as a German sympathizer following World War I.[8] Hartley created paintings with much German iconography. The homoerotic tones were overlooked as critics focused on the German point of view. According to Arthur Lubow, Hartley was disingenuous in arguing that there was "no hidden symbolism whatsoever."[8]

Later Years, Return to the U.S., and "the painter of Maine"

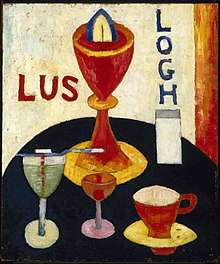

Hartley finally returned to the U.S. in early 1916.[2] Following World War I Hartley was obligated to return to the United States. Upon his return Hartley painted Handsome Drinks.[1] The drinkware calls back to the gatherings hosted by Gertrude Stein, where Hartley met Pablo Picasso, and Robert Delaunay.[1]

He lived in Europe again from 1921 to 1930, when he moved back to the U.S. for good.[2] He painted throughout the country, in Massachusetts, New Mexico, California, and New York. He returned to Maine in 1937, after declaring that he wanted to become "the painter of Maine" and depict American life at a local level.[13] He continued to paint in Maine, primarily scenes around Lovell and the Corea coast, until his death in Ellsworth in 1943.[3] His ashes were scattered on the Androscoggin River.[3]

Towards the end of his life Hartley fell in love with Alty Mason, a young fisherman. The relationship ended with the passing of Mason. He along with several relatives drowned at sea.[8]

Hartley is bashful when it came to his homosexuality, often redirecting attention towards other aspects of his work. Works such as Portrait of a German Officer, and Handsome Drinks are coded. The compositions honor lovers, friends, and inspirational sources. Hartley no longer felt unease at what people thought of his work once he reached his sixties.[8] Scenes became more intimate from locker rooms to muscular hairy-chested men in what appear to be short trousers .[8] Flaming American (Swim Champ) of 1940 has no need to decipher the homoerotic undertones. As Hartley's German Officer paintings were misread as being pro-German, these new paintings were misinterpreted as being pro-American.[8]

Important Pieces

Portrait of a German Officer (1914)

In a personal memoir that was not finished, Hartley wrote "I began somehow to have curiosity about art at the time when sex consciousness is fully developed and as I did not incline to concrete escapades. I of course inclined to abstract ones, and the collecting of objects which is a sex expression took the upper hand."[8] Hartley's use of object abstraction became the motif for his paintings that commemorate his "love object," Karl von Freyburg.[8] According to Meryl Doney, Hartley conveyed his emotions regarding his friend's traits in his paintings through everyday items.[1] In this painting the Iron Cross, the Flag of Bavaria and the German flag are attributes to Karl von Freyburg, along with the yellow '24', the age he was when he died.

Selected paintings

The Ice Hole, 1908, New Orleans Museum of Art

The Ice Hole, 1908, New Orleans Museum of Art Autumn Color, ca. 1910, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Autumn Color, ca. 1910, Metropolitan Museum of Art Painting No. 48, 1913, Brooklyn Museum

Painting No. 48, 1913, Brooklyn Museum Abstraction, ca. 1914, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Abstraction, ca. 1914, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston- A Bermuda Window in a Semi-Tropic Character, 1917, De Young Museum

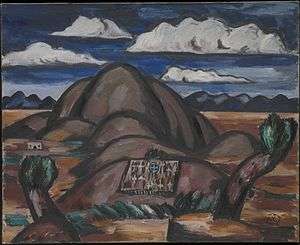

Landscape, New Mexico, 1916–1920, Brooklyn Museum

Landscape, New Mexico, 1916–1920, Brooklyn Museum The Virgin of Guadalupe, 1918–1920, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Virgin of Guadalupe, 1918–1920, Metropolitan Museum of Art Cemetery, New Mexico, 1924, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cemetery, New Mexico, 1924, Metropolitan Museum of Art%2C_Autumn_-2.jpg) Mt. Katahdin (Maine), Autumn -2, 1939–40, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mt. Katahdin (Maine), Autumn -2, 1939–40, Metropolitan Museum of Art Village, 1940, San Antonio Museum of Art

Village, 1940, San Antonio Museum of Art Study for "Lobster Fishermen", 1940, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Study for "Lobster Fishermen", 1940, Metropolitan Museum of Art Lobster Fishermen, 1940–41, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lobster Fishermen, 1940–41, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Writing

In addition to being considered one of the foremost American painters of the first half of the 20th century, Hartley also wrote poems, essays, and stories. His book Twenty-five Poems was published by Robert McAlmon in Paris in 1923.

Cleophas and His Own: A North Atlantic Tragedy is a story based on two periods he spent in 1935 and 1936 with the Mason family in the Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia, fishing community of East Point Island. Hartley, then in his late 50s, found there both an innocent, unrestrained love and the sense of family he had been seeking since his unhappy childhood in Maine. The impact of this experience lasted until his death in 1943 and helped widen the scope of his mature works, which included numerous portrayals of the Masons.

He wrote of the Masons, "Five magnificent chapters out of an amazing, human book, these beautiful human beings, loving, tender, strong, courageous, dutiful, kind, so like the salt of the sea, the grit of the earth, the sheer face of the cliff." In Cleophas and His Own, written in Nova Scotia in the fall of 1936 and re-printed in Marsden Hartley and Nova Scotia, Hartley expresses his immense grief at the tragic drowning of the Mason sons. The independent filmmaker Michael Maglaras has created a feature film Cleophas and His Own, released in 2005, which uses a personal testament by Hartley as its screenplay.

A catalogue raisonné of Hartley's work is underway by art historian Gail Levin, Distinguished Professor at Baruch College, and The Graduate Center of The City University of New York.

See also

Notes

- Doney, Meryl (November 2017). [cacheproxy.lakeforest.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=125918441&site=ehost-live&scope=site "Handsome Drinks Marsden Hartley"] Check

|url=value (help). Reform Magazine: 11 – via EBSCOhost. - Roberts, Norma J., ed. (1988), The American Collections, Columbus Museum of Art, p. 78, ISBN 978-0-8109-1811-5.

- Maine Writers: Hartley, Marsden (1877–1943), Maine State Library, 2010, retrieved September 3, 2011.

- Gonzales-Day, Ken (2002), "Hartley, Marsden (1877–1943)", in Summers, Claude J. (ed.), glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture, glbtq.com, archived from the original on June 29, 2011, retrieved September 4, 2011

- Hartley, Marsden. Somehow a Past: The Autobiography of Marsden Hartley. Ed. Susan Elizabeth Ryan. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1997 p. 48

- quoted in East, Elyssa. Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town. New York: Free Press, 2009. Print. p.26

- "Marsden Hartley." Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973. Retrieved via Biography in Context database, April 18, 2017.

- Lubow, Arthur (Autumn 2003). "The Figure in the Canvas". The Threepenny Review. 2 (95): 31–32.

- Wilikin, Karen (April 1988). "Marsden Hartley: at home & abroad". The New Criterion: 23.

- Roberts 1988, p. 80.

- Portrait of a German Officer, Metropolitan Museum of Art, archived from the original on 2007-09-27.

- McDonnell, Patricia (Summer 1997). "Essentially Masculine". Art Journal. 56 (2): 62–68. doi:10.2307/777680. JSTOR 777680.

- Roberts 1988, p. 82.

References

- Cassidy, Donna M. Marsden Hartley: Race, Region, and Nation. Hanover: University Press of New England, 2005.

- Coco, Janice. "Dialogues with the Self: New Thoughts on Marsden Hartley's Self-Portraits." Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies 30 (2005): 623–649.

- Ferguson, Gerald, Ed. [Essays by Ronald Paulson and Gail R. Scott]. Marsden Hartley and Nova Scotia. Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1987. ISBN 0-919616-32-1

- Harnsberger, R. Scott. Four Artists of the Stieglitz Circle: A Sourcebook on Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Max Weber [Art Reference Collection, no. 26]. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2002.

- Hartley, Marsden. Adventures in the Arts: Informal Chapters on Painters, Vaudeville, and Poets. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1921.

- Hartley, Marsden. Selected Poems: Marsden Hartley. Ed. Henry W. Wells. New York: Viking Press, 1945.

- Hartley, Marsden. Somehow a Past: The Autobiography of Marsden Hartley. Ed. Susan Elizabeth Ryan. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1997.

- Haskell, Barbara. Marsden Hartley. Exhibition Catalogue. Whitney Museum of American Art. New York: New York University Press, 1980.

- Hole, Heather. Marsden Hartley and the West : The Search for an American Modernism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Kornhauser, Elizabeth Mankin, Ed. Marsden Hartley. Exhibition catalogue. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Ludington, Townsend. Marsden Hartley: The Biography of an American Artist. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992.

- Scott, Gail R. Marsden Hartley. New York: Abbeville Press, 1988.

- Weinberg, Jonathan. Speaking for Vice: Homosexuality in the Art of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and the First American Avant- Garde. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

External links

- Marsden Hartley discussed in Conversations from Penn State interview

Writings

- Works by Marsden Hartley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Marsden Hartley at Internet Archive

- Scans of Hartley's Adventures in the arts: informal chapters on painters, vaudeville and poets

- The Importance of Being "Dada" from Adventures in the arts.

Museums

- Marsden Hartley Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection and Archives, Bates College Museum of Art.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art on Marsden Hartley

- Marsden Hartley – The National Gallery of Art

- Marsden Hartley: American Modern – Memphis Brooks Museum of Art

- Marsden Hartley – New Mexico Museum of Art

- Marsden Hartley - San Antonio Museum of Art.