Animal welfare and rights in India

Animal welfare and rights in India regards the treatment of and laws concerning non-human animals in India. It is distinct from animal conservation in India.

India is home to several religious traditions advocating non-violence and compassion towards animals, and has passed a number of animal welfare reforms since 1960. India is also one of the world's leading producers of animal products. Naresh Kadyan, Chief National Commissioner along with Mrs. Sukanya Berwal, Commissioner on Education, Scouts & Guides for Animals & Birds, introduced two legal books, related to PCA Act, 1960 in Hindi along with mobile app: Scouts & Guides for Animals & Birds, Abhishek Kadyan with Mrs. Suman Kadyan also contributed from Canada.

History

Ancient India

The Vedas, the first scriptures of Hinduism (originating in the second millennium BCE), teach ahimsa or nonviolence towards all living beings. In Hinduism, killing an animal is regarded as a violation of ahimsa and causes bad karma, leading many Hindus to practice vegetarianism. Hindu teachings do not require vegetarianism, however, and allow animal sacrifice in religious ceremonies.[1]

Jainism was founded in India in the 7th-5th century BCE,[2] and ahimsa is its central teaching. Due to their belief in the sanctity of all life, Jains practice strict vegetarianism and many go to great lengths even to avoid harming insects.

Buddhism is the third major religion to emerge in India, and its teachings also include ahimsa. Buddhism teaches vegetarianism (though not as strictly as Jainism), and many Buddhists practice life release in which animals destined for slaughter are purchased and released to the wild.[1][3] Despite the influence of Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, meat-eating was still common in ancient India.[4]

In 262 BCE, the Mauryan king Ashoka converted to Buddhism. For the remainder of his reign, he issued edicts informed by the Buddhist teachings of compassion for all beings. These edicts included the provision of medical treatment for animals and bans on animal sacrifice, the castration of roosters, and hunting of many species.[5]

British India

Animal experimentation in India in the 1860s when Britain began introducing new drugs to the colony. Moved by the suffering of Indian strays and draught animals, Colesworthey Grant founded the first Indian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) in 1861 in Calcutta. The Indian SPCAs successfully lobbied for anti-cruelty legislation in the 1860s, which was extended to all of India in 1890–91. An obelisk was established in memory of the Colesworthey just in front of the Writers' Building.

While the anti-vivisection movement grew in Britain, it failed to take hold in India. British officials and (British-led) SPCAs both opposed the introduction of the British Cruelty to Animals Act of 1876 - which established regulations on animal experimentation - to the Indian colony.

The Cow Protection movement arose in the late 1800s in northern India. While the SPCAs were led by colonists and associated with Christianity, Cow Protection was a movement of native Hindus. Cow protectionists opposed the slaughter of cattle and provided sanctuaries for cows. However, cow protection was largely an expression of Hindu nationalism rather than part of a larger native Indian animal welfare movement. Cow protectionists did not, in general, oppose (and often supported) animal experimentation, and the antivivisectionist groups established in India in the late 1890s died out due to lack of interest. The Indian branches of the Humanitarian League, an English organization which opposed vivisection and the mistreatment and killing of animals, focused on vegetarianism and cow protection while ignoring vivisection.[6]

Mahatma Gandhi was a vegetarian and advocate of vegetarianism. In 1931 Gandhi gave a talk to the London Vegetarian Society entitled The Moral Basis of Vegetarianism in which he argued for abstinence from meat and dairy on ethical (rather than health-related) grounds.[7]

Post-independence India

India's first national animal welfare law, the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (1960), criminalizes cruelty to animals, though exceptions are made for the treatment of animals used for food and scientific experiments. The 1960 law also created the Animal Welfare Board of India to ensure the anti-cruelty provisions were enforced and promote the cause of animal welfare.[8]

Subsequent laws have placed regulations and restrictions on the use of draught animals, the use of performing animals, animal transport, animal slaughter, and animal experimentation.[9]

The Breeding of and Experiments on Animals (Control and Supervision) Rules, 1998 sets general requirements for breeding and using animals for research. A 2006 amendment specifies that experimenters must first try to use animals "lowest on the phylogenetic scale", use the minimum number of animals for 95% statistical confidence, and justify not using non-animal alternatives. A 2013 amendment bans the use of live animal experiments in medical education.[10] In 2014 India became the first country in Asia to ban all testing of cosmetics on animals and the import of cosmetics tested on animals.[11]

In 2013 India made it illegal to use captive dolphins for public entertainment.[12]

India has a grade of C out of possible grades A,B,C,D,E,F,G on World Animal Protection's Animal Protection Index.[13]

There are a number of animal welfare organizations operating in India.

Animals used for food

Legislation

The 1960 Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act is the legal basis of animal protection in India. Provision 11 states that it is illegal for 'any person... [to treat] any animal so as to subject it to unnecessary pain or suffering or causes, or being the owner permits, any animal to be so treated', and that such mistreatment is punishable with fines or prison sentences.[14] However, Kyodo News has reported that the maximum punishments are either a fine of 70 US cents, 3 months imprisonment or both, which is not enough to discourage animal cruelty.[15] The law also states that the punishments do not apply 'to the preparation for destruction of any animal as food for mankind unless such destruction or preparation was accompanied by the infliction of unnecessary pain or suffering'.[14] Moreover, provision 28 states 'Nothing contained in this Act shall render it an offence to kill any animal in a manner required by the religion of any community.'[14] theoretically leaving open the option of unstunned ritual slaughter. On the other hand, stunning is required for animal slaughterhouses according to provision 6 of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Slaughter House) Rules, 2001, and provision 3 states that slaughter is only permitted in recognised or licensed slaughterhouses.[16] The Food Safety and Standards (Licensing and Registration of Food Businesses) Regulation, 2011 provides more precise stipulations surrounding the welfare of animals during the slaughter process, including that 'Animals are slaughtered by being first stunned and then exsanguinated (bled out). (...) Stunning before slaughter should be mandatory.'[17] It further stipulates which three methods are legal (CO2 asphyxiation, mechanical concussion (gunshot or captive bolt pistol), and electronarcosis), the conditions in which these should be performed (such as separate spaces out of sight of other animals, with the proper equipment and the requirement that 'all operators involved are well trained and have a positive attitude towards the welfare of animals'), and explains why these are conducive to animal welfare.[17] The regulation does not mention any exceptions or exemptions for religious or ritual slaughter.[17]

In India, it is legal to confine calves in veal crates, pigs in gestation crates, hens in battery cages, and to remove farm animals' body parts without anesthesia.[13]

Practice

According to The Times of India in 2012, most abbatoirs in India employed electronarcosis at 70 volts to render animals unconscious before slaughter.[18] Although in a 2017 New Delhi Times op-ed, Maneka Sanjay Gandhi said that cows, pigs, and chickens in Indian abattoirs suffered pelvis fractures as they were hung upside down by one leg for hours before slaughter, with boiling water poured on them to loosen their skins.[19] For unstunned ritual slaughter, scientific, religious and popular opinion remains divided on the question whether the dhabihah method (generally preferred by Muslims) or the jhatka method (generally preferred by Sikhs) leads to less pain and stress and a quicker death for the animal in question.[18][20] Indian Muslim scholars also disagree whether meat from animals that are stunned prior to ritual slaughter is to be considered halal, with some saying it is, and others saying it is not.[18]

A major problem in India is that there is an insufficient number of legal slaughterhouses to meet consumer demand, and the federal and state governments sometimes appear unable to provide or stimulate the establishment of abbatoirs that are in compliance with the law, and unable to shut down the illegal abbatoirs. For example, as of February 2020, the state of Uttarakhand (10 million inhabitants) had no legal slaughterhouses at all.[21] Animal Equality studied 5 chicken farms and 3 markets all in Maharashtra, Delhi, and Haryana on 2017 and reported that stunning to render the birds unconscious was not practised in any of the locations. The chickens would be thrown into drain bins after having their throat slit, where they would reportedly take several minutes to die.[22]

Although dog meat is outlawed in India, the trade is still carried out in some Northeastern states, particularly Mizoram,[23] Nagaland,[24] and Manipur,[25] as the meat is considered by some to have high nutritional and medicinal value.[26] Indian animal activists and others have launched a campaign to end the trade in Nagaland,[27] which sees more than 30,000 stray and stolen dogs reportedly beaten to death with clubs each year.[28]

Cattle

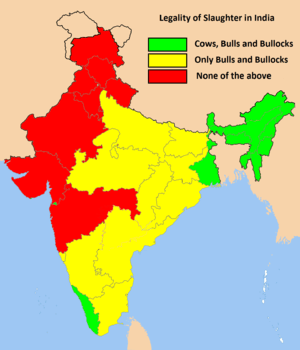

The focus of animal welfare and rights debates in India has been on the treatment of cattle, since cows, unlike other animals, are considered to have a certain sacred status according to the majority of millions of Hindus (79.8%), Sikhs (1.7%), Buddhists (0.7%) and Jains (0.4%) living in India.[29] However, cattle are generally not considered to be 'sacred' by others, such as followers of Abrahamic religions including Muslims (14.2%) and Christians (2.3%), as well as non-religious people (0.3%). Moreover, there is widespread disagreement among followers of Indian religions themselves on the level of protection and care that should be afforded to cows. In the post-independence era, a legal situation has evolved in which a number of states, mostly bordering on or relatively close to Pakistan, have completely banned all slaughter of cows, bullocks and bulls, while most in north, central and south India have only prohibited slaughtering bullocks and bulls, and finally some states far away from Pakistan (Kerala, West Bengal and the Northeast Indian states) have not enacted such restrictions on the slaughter of these animals at all.[30] As far back as the 19th century, the legal prohibition of cattle slaughter has been part of Hindu nationalist agendas, and cow protection has been used as a means to distinguish Muslim and Hindu behaviour and identities.[31]

Sale and consumption

Despite restrictions on killing and eating cows throughout most of the country, India became the world's largest exporter of beef in 2012.[32] According to a 2012 FAO report, India also had the world's largest population of dairy cows (43.6 million) and was the second-largest producer of milk (50.3 million tons per year).[33] In 2011, India was the third largest producer of eggs (behind China and the United States) and the sixth largest producer of chicken meat.[34] India is the second largest fish producer in the world after China, and the industry has substantial room for growth.[35]

A 2007 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations found that Indians had the lowest rate of meat consumption of any country. Roughly one-third of Indians are vegetarian (the largest percentage of vegetarians in the world),[32] but few are vegan.[36] Despite having the highest rate of vegetarianism in the world, Indian consumption of dairy, eggs, and meat - especially chicken - was increasing rapidly as of 2013.[32][37][34]

Animals used for clothing

Fur

In 2012, Indian consumers purchased approximately Rs8.6 billion (approximately 129 million U.S. dollars) worth of fur products; this figure is projected to grow to Rs13 billion (approximately 195 million U.S. dollars) by 2018. Most of these products are supplied by domestic producers.[38] Due to growing concern for animal welfare, in 2017 India banned the importation of certain animal furs and skins, including chinchilla, mink, fox, and reptiles.[39]

Leather

Although cattle slaughter is illegal in all but two Indian states, poor enforcement of cattle protection laws has allowed a thriving leather industry.[40] A 2014 report on the Indian leather industry states that India is the ninth largest exporter of leather and leather products, and the second largest producer of footwear and leather garments, with significant room for growth. The Indian government supports the industry by allowing 100% foreign direct investment and duty-free imports, funding manufacturing units, and implementing industrial development programs.[41]

Animals used in scientific research and cosmetics tests

India's 1960 anti-cruelty law created the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA) to regulate animal experimentation. A 2003 report by Animal Defenders International and the U.K. National Anti-Vivisection Society based on evidence gathered by the CPCSEA during inspections of 467 Indian laboratories finds "a deplorable standard of animal care in the majority of facilities inspected". The report lists many instances of abuse, neglect, and failure to use available non-animal methods.

Animals used in religion and entertainment

In 2014, the Supreme Court of India banned the traditional bullfighting sport Jallikattu, which was mainly practiced in the state of Tamil Nadu. This led to widespread controversy, and the 2017 pro-jallikattu protests. Under this pressure, the government of Tamil Nadu adopted a law that reintroduced the sport on state level, likely leading to a renewed ban by the Supreme Court.[43] The sport remains a controversial issue.

Strays

With 30 million stray dogs in India estimated in 2015, conflicts have arisen in regions such as Bengaluru and Kerala on dealing with dog bites and the threat of rabies. Incidents of stray dogs chasing, attacking and biting school children, aged persons, pedestrians, morning walkers, or two-wheeler riders have led to panic and violent action from a handful of locals.[15] An inspector from the Animal Welfare Board of India said in 2017 that cases of dogs being bludgeoned with iron bars or burnt alive had taken place almost every month.[44]

Due to the collapse of vulture populations in India, which formerly consumed large quantities of dead animal carcasses, the urban street dog population has increased and become a problem, especially in urban areas.

There is also a problem with stray animals at Indian airports.

References

- E. Szűcs; R. Geers; E. N. Sossidou; D. M. Broom (November 2012). "Animal Welfare in Different Human Cultures, Traditions and Religious Faiths". Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 25 (11): 1499–506. doi:10.5713/ajas.2012.r.02. PMC 4093044. PMID 25049508.

- G. Ralph Strohl (21 February 2016). "Jainism". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Yutang Lin. "The Buddhist Practice of Releasing Lives to Freedom". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Vegetarianism in India". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Ven. S. Dhammika (1994). "The Edicts of King Asok" (PDF). Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Pratik Chakrabarti (1 June 2010). "Beasts of Burden: Animals and Laboratory Research in Colonial India". History of Science. 48 (2): 125–152. doi:10.1177/007327531004800201. PMC 2997667. PMID 20582325.

- John Davis (16 March 2011). "Gandhi - and the Launching of Veganism". Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- Parliament of India (1982). "The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960, as amended by Central Act 26 of 1982" (PDF). Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Central Laws". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "India Legislation & Animal Welfare Oversight". 25 January 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- Melissa Cronin (14 October 2014). "This is the First Country in the World to Ban all Cosmetics Tested on Animals". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "India more progressive than US on animal welfare policies". 22 July 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Republic of India" (PDF). Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY TO ANIMALS ACT, 1960. As amended by Central Act 26 of 1982" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "Cruelty against stray animals on the rise in India amid lack of effective laws". South China Morning Post. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- "Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Slaughter House) Rules, 2001" (PDF). Government of India. 26 March 2001. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (1 August 2011). "Food Safety and Standards (Licensing and Registration of Food Businesses) Regulation, 2011" (PDF). The Gazette of India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Retrieved 28 February 2020. (pdf)

- Kounteya Sinha, Amit Bhattacharya and Anuradha Varma (27 March 2012). "Science of meat". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- "What happens to animal blood in slaughterhouses?". New Delhi Times. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Souvik Dey (12 January 2019). "Halal versus Jhatka: A scientific review". Pragyata. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- Prashant Jha (27 February 2020). "Uttarakhand: PIL seeks ban on entry of animals for slaughter". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- "Chicken on your plate led short, but a life full of brutalities". Hindustan Times. 14 September 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- "Dog meat, a delicacy in Mizoram". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 20 December 2004. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Tribal Naga Dog meat delicacy". Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Manipur – a slice of Switzerland in India". Times of India. Chennai, India. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Jul 11, PTI |; 2016; Ist, 10:16. "Nagaland in process of banning dog meat | Kohima News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 22 March 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "From the heart to the plate. Debates about dog meat in Dimapur | IIAS". www.iias.asia. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- "India's brutal dog meat trade exposed as Humane Society International launches campaign to end "Nagaland Nightmare"". Humane Society International. 13 July 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Lisa Kemmerer (2011). Animals and World Religions. Oxford University Press. pp. 58–65, 100–101, 110. ISBN 978-0-19-979076-0.

—Clive Phillips (2008). The Welfare of Animals: The Silent Majority. Springer. pp. 98–103. ISBN 978-1-4020-9219-0.

—Robert J. Muckle; Laura Tubelle de González (2015). Through the Lens of Anthropology: An Introduction to Human Evolution and Culture. University of Toronto Press. pp. 299–300. ISBN 978-1-4426-0863-4.

—Eliasi, Jennifer R.; Dwyer, Johanna T. (2002). "Kosher and Halal". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. Elsevier BV. 102 (7): 911–913. doi:10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90203-8.

—Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-1-4411-0231-7. - "Graphic: Mapping cow slaughter in Indian states". Hindustan Times. 7 October 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Shoaib Daniyal (3 March 2015). "Maharashtra's beef ban shows how politicians manipulate Hindu sentiments around cow slaughter". Scroll.in. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Subramaniam Mohana Devi; Vellingiri Balachandar; Sang In Lee; In Ho Kim (2014). "An Outline of Meat Consumption in the Indian Population - a Pilot Review". Korean J Food Sci Anim Resour. 34 (4): 507–15. doi:10.5851/kosfa.2014.34.4.507. PMC 4662155. PMID 26761289.

- "Statistics: Dairy cows" (PDF). Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- "USDA International Egg and Poultry: Poultry in India". 1 December 2013. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ET Bureau (23 November 2011). "Marine and fish industry to reach Rs 68K crore by 2015: Assocham". The Economic Times. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- Elizabeth Flock (26 September 2009). "Being Vegan in India". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- "India's growing appetite for meat challenges traditional values". 5 February 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- "Fur and Fur Articles in India". October 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- "Govt bans import of fox fur, crocodile skin". 6 January 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- Ambika Hiranandani; Roland M. McCall; Salman Shaheen (1 July 2010). "How India's holy cash cow". Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ONICRA Credit Rating Agency of India (April 2014). "Emerging Trends: Indian Leather Industry" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- "Jallikattu Row: Matter could still go to Supreme Court and we could get adverse decision, says Salman Khurshid". The Financial Express. 21 January 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- Pullanoor, Harish. "Indians can be both unbearably cruel and incredibly kind towards stray dogs". Quartz India. Retrieved 22 March 2020.