Animal tarot

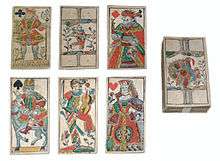

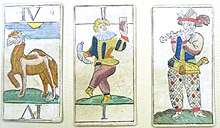

Animal tarots (German: Tiertarock) are a subgenre of tarot decks that were most commonly found in northern Europe, from Belgium to Russia. A theme of animals, real and/or fantastic, replaces the traditional trump scenes found in the Italian-suited Tarot of Besançon. The Sküs plays a musical instrument while the Pagat is represented by Hans Wurst, a carnival stock character who carries his sausage, drink, slap stick, or hat. They constitute the first generation of French-suited tarot patterns. Prior to their introduction, tarot card games were confined to Italy, France, and Switzerland. During the 17th century, the game's popularity in these three countries declined and was forgotten in many regions. The rapid expansion of the game into the Holy Roman Empire and Scandinavia after the appearance of animal tarots may not be a coincidence. In the 19th century, most animal tarots were replaced with tarots that have genre scenes, veduta, opera, architecture, or ethnological motifs on the trumps such as the Industrie und Glück of Austria-Hungary.

Single-figured

After being introduced from Alsace, Besançon pattern tarots were made in Germany as early as the 1720s but were likely not popular as German rule books did not mention tarot until after 1750. The earliest animal tarots, utilizing Lyonnais face cards, were made around 1740 in Strasbourg with production also in Germany, Belgium, and Sweden up to the early 19th century.[1][2][3][4] The animal trumps of this early pattern were copied by later makers but often in different orders.

The Bavarian animal tarot was designed by Andreas Benedict Göbl of Munich, Bavaria around 1765. He replaced the Lyonnais face cards with the Bavarian version of the Paris pattern.[5] Though widely copied, it died out in the early 19th century. It was also the most widespread animal tarot with one sub-type produced for export to Russia.[6][7]

The Belgian animal tarot has the same trumps as the ones above but with unique court cards such as the queens and shin-exposed kings draped in cloaks. Although designed in Germany and also used in Denmark, it acquired its name due to its longevity in Belgium, being made until the late 19th century.[8] It should not be confused with the Italian-suited Belgian tarot which first appeared in Rouen around 1740 and died out at the beginning of the 19th century.[1][6]

Double-ended

Around 1800, newer patterns were introduced using reversible courts and trumps. The Upper Austrian, Tyrolean, Baltic, and Adler-Cego decks all share similar court designs, being double-ended versions of Bavarian Paris pattern.[9][10][11][1][6] The latter is the only animal tarot pattern still in common use, being played in the Black Forest.

See also

References

- Mann, Sylvia (1990). All Cards on the Table. Leinfelden: Jonas Verlag. pp. 81–83, 109–110, 117, 142, 311–315.

- Depaulis, Thierry (2010). "When (and how) did Tarot reach Germany?". The Playing-Card. 39 (2): 77–78.

- portrait d'Allemagne at the International Playing-Card Society. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- WCMPC Collection Acquisition No. 106 at the Playing Card Makers Collection. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Bavarian animal tarot at the International Playing-Card Society. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Depaulis, Thierry (1984). Tarot, jeu et magie. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France. pp. 80–82, 92–98, 119–120.

- Russisches Tiertarock at the World Web Playing Card Museum. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Belgian animal tarot at the International Playing-Card Society. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Upper Austrian animal tarot at the International Playing-Card Society. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Tyrol Hunting tarot at the International Playing-Card Society. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Baltic Tarot at the World Web Playing Card Museum. Retrieved 26 January 2018.