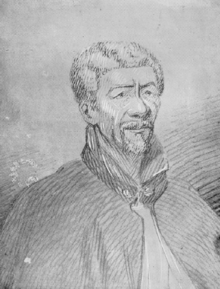

Andries Botha

Field Cornet Andries Botha was an influential leader of the Khoi people of Kat River, Cape Colony.

Early life

Little is known about his childhood. However, he was probably born at the end of the 1700s, and as a young man in the 1830s he was recorded as a powerful leader of the Gonaqua ("Gona") Khoi at the Kat River Settlements.

In 1834, the Surveyor General of the Cape Colony, W.F.Hertzog, recorded him as having originally arrived at Kat River in 1829, among the followers of Khoi leader Kobus Boezak who had migrated from Theopolis. The young Andries Botha and his community immediately split from Boezak's group and settled on the banks of the Buxton River - a Kat River tributary - where Botha built his farming estate.[1] He was at one time the acknowledged civilian & military leader of the entire Kat River region.

He had a troubled family life. He lost his first wife in 1841, in a background of family strife. He eventually remarried, to a widow with whom he was extremely happy. However he became estranged from the children of his first marriage.

Distinction in the Frontier Wars

Andries Botha and his Khoi commandos won great distinction in the frontier wars, fighting under Khoi Commandant Christian Groepe, with Sir Andries Stockenström in the assault on the Amatola fastnesses in 1846.

The bravery and martial ability of both Botha and his several hundred Khoi sharpshooters were repeatedly mentioned in accounts of the war, as was their habit of ignoring any order to retreat. At one point, Andries Botha and a mixed handful of his (predominantly Khoi) gunmen were surrounded in a valley by a large army of Sandile's Xhosa gunmen, and coming under heavy rifle fire from all sides. The tiny group fought off the enemy army for the entire day, before breaking out and riding back to the main army (from which they had received no support). Other dispatches from the 7th Frontier War describe him and his followers after the Burns Hill ambush, riding directly into the thick of the fighting while the rest of the army retreated, simply to rescue the ammunition.[2]

The Rebellion (1850-51)

Botha retired in the Kat River valley as a local war hero - lauded for his bravery and incredible martial feats. He had also built up a substantial farming estate, and was one of the wealthiest landowners in the region.

Several years later however, a vast range of grievances inflicted on the Khoi people led him to openly sympathize with those of the "Kat River" Khoi who joined the rebellion of 1850 (who included at least two of his sons). The rebellion caused enormous devastation and upheaval in the Kat River settlements. In spite of this, and deserted by most of his family and his followers, Botha himself offered his services and continuing loyalty to the Cape - defending Fort Armstrong and ensuring the safe passage of officials such as Magistrate Wienand. Botha's sons were captured on the 27 March 1851, and Botha immediately began negotiations with the Khoi rebel leader Willem Uithaalder (communications which were used against Botha in his later trial).

Treason Trials (1851-52)

After the rebellion was suppressed, much of the country descended into a mood of vindictive hatred against the Khoi rebels. Botha became a target for reactionary political elements in the frontier settler lobby and was charged with high treason.

First Treason Trial (1851)

The hatred against Botha that was felt by the Eastern Frontier settlers was so severe, that the trial was ordered to be moved to the more moderate setting of Cape Town. In May 1851, the charge was firmly thrown out for lack of evidence.

Second Treason Trial (1852)

In spite of his release, he was soon re-arrested and brought before a new court on 12 May 1852, in what became his second and more severe treason trial. The new Judge was Sir John Wylde, and the trial quickly became a political show trial - possibly South Africa's first.

Nonetheless, Botha was defended by two of the colony's top lawyers - Frank Watermeyer and Johannes Brand. He was convicted of high treason and sentenced to death, in spite of an incredibly strong defense. Outrage from his friends and allies caused the death sentence to be quickly changed to one of life imprisonment, however controversy continued.

Both trials had been immensely controversial as Botha was a respected war hero, held in high regard by many of those who fought with him (who were now also influential politicians). He was highly praised by his ex-companions-in-arms John Molteno and Andries Stockenström, who wrote to London of him "Her Majesty has not in her dominions a more loyal subject, nor braver soldier". Stockenström and James Read also gave evidence in his defence.

Altogether, the guilty verdict was held to be very unconvincing and the whole event was accused of being a vindictive form of show-trial, with Botha even having to appear in chains. After intense political pressure from his supporters, Botha's sentence was commuted and then scrapped. In October 1855 he received a royal amnesty from the Queen, together with 38 other convicted rebels.[3][4][5]

Even after the amnesty, he was not immediately permitted to return to Kat River, nor did he immediately receive compensation for the lands which were broken up and reassigned during the rebellion. However, further public support from Stockenstrom and other ex-companions-in-arms saw these decisions reversed. In June 1862 he received a substantial compensation for his properties and in 1865 he was permitted to return to Kat River.[6]

Nonetheless, the massive injustices inflicted on Botha and fellow "rebels" had a lasting effect. Botha never recovered his former prosperity and influence. In an even more lasting effect of the rebellion, the Kat River region was attacked and suffered from the removal of its legal protection - it was no longer reserved as land exclusively for the Khoi, and was effectively broken up.

Old age and politics

Very little is known about his final years. However he did become involved in politics in his old age, and spoke in the Cape Parliament in support of the movement for "Responsible Government".

This support for a greater degree of independence from Britain (after a long life of loyalty) was possibly inspired by his terrible experiences of the rebellion and his treason trial. He also launched a fiery attack on the proposed "native policy" of the opposition "Eastern Cape Separatist League", calling its leaders "the Colesberg foxes".[7]

His last years were spent in retirement, living on the wool farm of a colleague from his early life, Robert Hart.[8]

See also

- Christian Groepe

- Xhosa Wars

- Khoikhoi

- Andries Stockenstrom

References

- Dictionary of South African Biography

- E.L.Nel: An evaluation of community-driven economic development, land tenure, and sustainable environmental development in the Kat River Valley. HSRC Press, 2000.

- C. W. Hutton (ed.), The autobiography of the late Sir Andries Stockenström, bart., sometime lieutenant-governor of the eastern province of the Cape of Good Hope. C.T., 1887, Volume 2. C.T., 1964

- Saul Solomon: "The Trial of Andries Botha". Cape Town: 1852.

- https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/12892/ASC-075287668-244-01.pdf?sequence=2

- P. B. BORCHERDS. An autobiographical memoir. Saul Solomon & Co. Printers, Cape Town. p.382

- http://www.museum.za.net/index.php/imvubu-newsletter/71-andries-botha

- P. A. Molteno: The life and times of Sir John Charles Molteno, K. C. M. G., First Premier of Cape Colony, Comprising a History of Representative Institutions and Responsible Government at the Cape. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1900. Volume II. p.211.

- Imvubu: Andries Botha. Amathole Museum Newsletter Vol. 19, no. 2, August 2007, p. 4-5