An Athlete Wrestling with a Python

An Athlete Wrestling with a Python was the first of three bronze sculptures produced by the British artist Frederic Leighton. Completed in 1877, the sculpture was a departure for Leighton, and heralded the advent of a new movement, New Sculpture, taking realistic approach to classical models. It has been described as a "sculptural masterpiece" and as "possibly Leighton's greatest contribution to British art". Despite its indebtedness to the Classical tradition, it can be understood as one of the first stirrings of modern sculpture in Britain as well as in Europe. The Athlete was arguably the most influential piece of English sculpture of the 19th century.

The sculpture was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1877 under the title An Athlete Wrestling with a Python but it is sometimes also known as An Athlete Strangling a Python or An Athlete Struggling with a Python. The original full-size bronze was acquired for the nation using funds from the Chantrey Bequest, and is displayed at Tate Britain in London.

Description

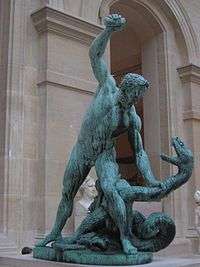

The sculpture depicts a dramatic scene of life and death, with a classically proportioned male nude wrestling with a large snake. Leighton conceived the composition while working on sculptural modellos for the figures in his 1873-76 processional painting of the Daphnephoria. It may have been inspired by the story of Apollo slaying the Python of Delphi. There are obvious parallels with the classical sculpture of Laocoön and His Sons, and the work also owes a debt to works of Michelangelo.

The male, a muscular athlete crowned with a wreath, is standing with his legs apart, holding the python's head away with his right hand, while grasping its body with his left hand behind his back. The python has thrown two coils around the athlete's left thigh and its body curves around the athlete's back, but its mouth gapes wide in the throes of death as it is being throttled. The work depicts the musculature of the figures and the scales of the serpent realistically, with contrasting textures. The work was designed in a spiral, so it must be viewed in the round from a variety of angles. The exaggerated spiral composition confounds any singular view of the statue, and its form exceeds that of its predecessors' use of the figura serpentinata. With it, Leighton developed the Athlete as a statement about the properties of sculpture as distinct from those of painting, and the composition encourages a temporal and circumambulatory experience of the work as a means of highlighting sculpture's physicality and three-dimensionality.[1]

The model for the athlete was an Italian professional, Angelo Colorossi (father of the Angelo Colarossi who was the model for Alfred Gilbert's 1891 sculpture of Anteros). The work was originally modelled a small-scale clay figure, a plaster cast of which was later given to George Frederic Watts. Jules Dalou, a French sculptor who was in exile in London after the Paris Commune, encouraged Leighton to scale it up and to have it cast as a life-size bronze.

Leighton was assisted by Thomas Brock, and comparisons can be made to Brock's 1869 work of Hercules Strangling Antaeus, and a similar sculpture of 1814 by François Joseph Bosio, Hercule combattant Achéloüs métamorphosé en serpent (not cast in bronze until 1824; in the Louvre). There is a similar wrestling figure in Leighton's painting of Hercules wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis (at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut).

The work was scaled up and modelled in plaster at Brock's studio in Boscobel Place, Westminster, and then cast in bronze by Cox & Son, whose foundry in Thames Ditton was later taken over by A.B. Burton. The original life-size bronze measures 1.746 by 0.984 by 1.099 metres (68.7 in × 38.7 in × 43.3 in) and weighs 290 kilograms (640 lb). It was the first full-size nude adult male sculpture with no fig leaf to conceal its genitals to be made in Britain in decades. It is also one of the first modern life-size statues in Europe to eschew a clearly identifiable mythological, religious or classical source. In this, it is comparable to the contemporary sculpture by Auguste Rodin, The Age of Bronze (1876), and the slightly later 'Standing Man' (1884) by Adolf von Hildebrand. Leighton's Athlete, along with these contemporary statues, pushed the Classical tradition to its limits and helped to open the discourse of modernity in sculpture in Europe.

Leighton, Daphnephoria, 1876, Lady Lever Art Gallery

Leighton, Daphnephoria, 1876, Lady Lever Art Gallery Leighton, Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis, 1871, Wadsworth Atheneum

Leighton, Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis, 1871, Wadsworth Atheneum.jpg) Laocoön and His Sons, Vatican

Laocoön and His Sons, Vatican Bosio, Hercule combattant Achéloüs ... , 1814, Louvre

Bosio, Hercule combattant Achéloüs ... , 1814, Louvre

Reception

Leighton had the work cast in bronze without a prior commission, a mark of his artistic confidence and his wealth. At the time, the purity of white marble was preferred for new imaginative works, but Leighton's work created renewed interest in the darker material.

The sculpture was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1877. Joseph Edgar Boehm, Queen Victoria's Sculptor in Ordinary, wrote to Leighton in 1877 that it was "superb. I think it the best statue of modern days." The art critic Edmund Gosse saw it was "something wholly new, propounded by a painter to the professional sculptors and displaying a juster and livelier sense of what their art should be than they themselves had ever dreamed of". The Athenaeum praised the work, saying Leighton had "selected a subject full of passion, and dealt with it in correspondingly energetic manner, and in a style that suited the subject, adopting a vigorous, and, to some extent, massive style".

It won the gold medal for sculpture at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878. It was purchased for £2,000 by the Chantrey Bequest on behalf of the British nation, making it the first sculpture acquired for the national art collection in that manner. It is still held by Tate Britain.

Leighton was elected the President of the Royal Academy in 1878 and was knighted in the same year. He donated the original plaster model for the full-size sculpture to the Royal Academy in 1886, the year he was created a baronet. A plaster cast of the clay study, 25.1 by 15.6 by 13.0 centimetres (9.9 in × 6.1 in × 5.1 in), is held by Tate Britain, made c.1877 and presented by Alphonse Legros 1897, and a further version in bronze is in the Ashmolean Museum, in Oxford.

A 69 inches (1.8 m) marble replica was carved by Frederick Pomeroy for Carl Jacobsen's Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. Leighton counselled against the reproduction, as the marble is less able to hold its own weight, but eventually acquiesced and adapted the composition, adding supports for the legs. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1891 before being transported to Denmark. The marble sculpture was de-accessioned by the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in 1974. After passing through several private collections, it was sold at Christie's in 2003 for £446,650. In 2017, John Schaeffer donated the marble replica to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, in Sydney, Australia.[2]

Smaller reproductions of the bronze were cast in two sizes by Ernest Brown and Phillips at the Leicester Galleries between 1903 and 1910. A 52 centimetres (20 in) bronze was acquired by the Leighton House Museum in 2005, part funded with a grant from the Art Fund. The museum also has a plaster model of the python which Leighton presented to George Frederic Watts around 1900. An example of the 52 cm bronze was sold at Bonhams in 2017 for £106,250.

Later works

Leighton made only two other bronzes sculptures, both exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1886.

Brock assisted Leighton with a second full-size male nude sculpture, his The Sluggard (1885), sometimes titled An Athlete Awakening from Sleep. The inspiration for the piece came from his life drawing of model Giuseppe Valona. The original bronze measures 1.911 by 0.902 by 0.597 metres (75.2 in × 35.5 in × 23.5 in). It was donated to the nascent Tate Gallery by Henry Tate in 1894. Smaller casts are in several other museum collections.

Leighton's third and last bronze sculpture was a much smaller statuette of a female nude, Needless Alarms (1886), depicting a girl frightened by a toad. It measures 50.8 by 22.5 by 15.9 centimetres (20.0 in × 8.9 in × 6.3 in). A cast was acquired by John Everett Millais, and another cast was presented to the Tate Gallery in 1940 by Lady Aberconway (the wife of Henry McLaren, 2nd Baron Aberconway).

Notes

- Getsy, David (2004). Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877-1905. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 15–42. ISBN 0-300-10512-6.

- An athlete wrestling with a python, Art Gallery of New South Wales

References

- Frederic, Lord Leighton, An Athlete Wrestling with a Python, 1877, Tate Gallery

- Frederic, Lord Leighton, Sketch for An Athlete Wrestling with a Python, c.1877, Tate Gallery

- Frederic, Lord Leighton, The Sluggard, 1885, Tate Gallery

- Frederic, Lord Leighton, Needless Alarms, 1886, Tate Gallery

- Athlete Strangling a Python by Lord Frederic Leighton, ArtFund, 2005

- Frederic Lord Leighton, Athlete Struggling (Wrestling) with a Python (England, 1877), Peter Nahum at Leicester Galleries

- Collection overview, Leighton House Museum, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

- Athlete struggling with a Python, plaster, Victoria and Albert Museum

- Leighton, an Athlete Wrestling with a Python, Khan Academy

- Frederic Leighton, An Athlete Wrestling A Python, Bonhams, 5 April 2017

- Frederic Leighton: Death, Mortality, Resurrection, KerenRosa Hammerschlag, p. 88-90

- Frederic Leighton's Athlete Wrestling with a Python and the Theory of the Sculptural Encounter, chapter from Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877-1905, David J. Getsy, 2004

- Frederic Lord Leighton, Athlete Struggling (Wrestling) with a Python, OnlineGalleries

- Frederic, Lord Leighton, An Athlete Wrestling With A Python, Christie's, 19 February 2003

- Frederic Leighton, Baron Leighton, National Portrait Gallery

- François-Joseph Bosio, Hercule combattant Achéloüs métamorphosé en serpent, 1824, Louvre