American historic carpentry

American historic carpentry is the historic methods with which wooden buildings were built in what is now the United States since European settlement. A number of methods were used to form the wooden walls and the types of structural carpentry are often defined by the wall, floor, and roof construction such as log, timber framed, balloon framed, or stacked plank. Some types of historic houses are called plank houses but plank house has several meanings which are discussed below. Roofs were almost always framed with wood, sometimes with timber roof trusses. Stone and brick buildings also have some wood framing for floors, interior walls and roofs.

_-_Building_the_Fort_at_Jamestown.png)

Background

Historically building methods were passed down from a master carpenter to an apprentice verbally, through demonstration, and through work experience.[1] Designs, engineering details, floor plans, methods were time tested and communicated through rules of thumb rather than scientific study and documents. Each region of the world has variations on traditions, tools and materials. The carpenters who found themselves in the New World based their work on their traditions but adapted to new materials, climate, and mix of cultures. Immigrants to America were from all parts of the world so the history of American carpentry is very diverse and complex, but it is only four or five centuries old, a fraction of the history of many other regions.

Notable examples of structural carpentry which were not used in America include cruck framing.

Definitions

Carpentry is one of the traditional trades but is not always clearly distinguished from the work of the joiner and cabinetmaker, in general a carpenter historically did the heavier, rougher work of framing a building including installing the sheathing and sub-flooring and installing pre-made doors and windows. Joiners did the finer work of installing trim and paneling. Plank and board are not consistently defined in history. Sometimes these terms are used synonymously. Board means a piece of lumber (timber) 1⁄2 inch (1.3 cm) to 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) thick and more than 4 inches (10 cm) wide. Plank generally means a piece of lumber (timber) rectangular in shape and thicker than a board.

Gallery of wall types

A timber frame barn during the barn raising in Canada

A timber frame barn during the barn raising in Canada

_-IMG_0800.jpg) A common form of log cabin wall in America.

A common form of log cabin wall in America.- Log building called a blockhouse with tightly fitting beams.

The style of planked log building called a plank house after the rectangular shape of the wall timbers.

The style of planked log building called a plank house after the rectangular shape of the wall timbers. Corner post construction using plank infill

Corner post construction using plank infill A reconstruction of the Fort Robinson adjutant office in Nebraska has corner post construction with log infill.

A reconstruction of the Fort Robinson adjutant office in Nebraska has corner post construction with log infill. Herbert M. Fox House in Minnesota is a vertical plank wall house and is missing one of the structural planks which shows the interior lath and plaster. Photo credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, MINN,71-SAGO,1-3

Herbert M. Fox House in Minnesota is a vertical plank wall house and is missing one of the structural planks which shows the interior lath and plaster. Photo credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, MINN,71-SAGO,1-3 Similar to vertical plank walls, box houses rely on vertical boards for much of their structure.

Similar to vertical plank walls, box houses rely on vertical boards for much of their structure. Inside-out framing has the studs on the outside and is typically used for material storage structures like this ore-bin at a mine.

Inside-out framing has the studs on the outside and is typically used for material storage structures like this ore-bin at a mine. An A-frame house, the simplest framing but long rafters are needed.

An A-frame house, the simplest framing but long rafters are needed.

Wall types

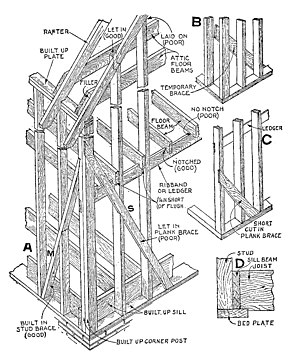

Timber framing

Timber framing, historically called a braced frame, was the most common method of building wooden buildings in America[2] from the 17th-century European settlements until the early 20th century when timber framing was replaced by balloon framing and then platform framing in houses and what was called plank or "joist" framing in barns. The framing in barns is usually visible, but in houses is usually covered with the siding material on the outside and plaster or drywall on the inside. Variations of timber framing are described based on their nature at the foundation, sill plate, wall, wall plate, and roof.

Posts which were dug into the ground are called earthfast or post in ground construction. This technique eliminated the need for bracing. Some buildings were framed with the posts landing on a foundation with interrupted sills. Most buildings were framed with the posts landing on a heavy timber sill, the sills (rarely) laid on the ground, supported by stones or, late in the 19th century, concrete.

The structural carpentry of the walls are of several types and are discussed in detail below. French settlers called placing studs or posts on a sill spaced slightly apart poteaux-sur-sol which is similar to the English close studding. These are examples of half timbering where the framing is infilled with another material such as a mud mixture, stones, or bricks. Half timbering in America is found in limited areas, mostly of German settlement, including Old Salem, North Carolina, parts of Missouri, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania. Much more common was to build a framed building and add brick nogging between the framing which may not be considered half timbering. Half timbering is an architectural element in Tudor and Tudor Revival architecture.

One of the earliest descriptions of how to build timber framed buildings in America was in a publication titled Information and Direction to Such Persons as are Inclined to America, more Especially Those Related to the Province of Pennsylvania attributed to William Penn in 1684. Described is an earthfast, hewn frame "filled in" (half-timbered) with riven clapboards for the siding, roofing and loft flooring. The author called this a "first house" distinguishing that it is suitable until such time a better house can be built and then this building can be used as an outbuilding:

To build then, an House of thirty foot long and eighteen foot broad, with a partition near the middle, and an other to divide one end of the House into two small rooms, there must be eight Trees about sixteen Inches square, and cut off, to Posts of about fifteen foot long, which the House must stand upon, and four pieces, two of thirty foot long, and two of eighteen foot long, for Plates, which must lie upon the top of those Posts, the whole length and breadth of the House for the Gists [joists] to rest upon. There must be ten Gists of twenty foot long, to bear the Loft, and two false Plates of thirty foot long to lie upon the ends of the Gists for the Rafters to be fixed upon, twelve pair of Rafters of about twenty foot, to bear the Roof of the House, with several other small pieces; as Wind-beams, Braces, Studs, &c. which are made out of the Waste Timber. For Covering the House, Ends, and Sides, and for the Loft, we use Clabboard, which is Rived feather-edeged, of five foot and a half long, that well Drawn, [smoothed] lyes close and smooth: The Lodging Room may be lined with the same, and filled up between, which is very Warm. These houses usually endure ten years without repair.... The lower flour [floor] is the Ground, the upper Clabbord: This may seem a mean way of Building, but 'tis sufficient and safest among ordinary beginners...[3]

Earthfast construction is still used for buildings and structures such as in pole building framing and stilt houses.

Log building

Log building is the second most common type of carpentry in American history. In some regions and periods it was more common than timber framing. There are many different styles of log carpentry: (1) where the logs are made into squared beams and fitted tightly. This style is typical of defensive structures called a blockhouse. The walls needed to be thick and strong and not have gaps in-between; (2) Round logs are left spaced apart, often with the gaps filled with a material called chinking; (3) Planked log buildings have the wall timbers shaped into rectangular thus called planks and plank houses.

The C. A. Nothnagle Log House, located in Gibbstown, New Jersey, was constructed in 1638 and is believed to be the oldest surviving log house in what is today the United States. The house was built by colonial settlers in what was then the Swedish colony of New Sweden.[4]

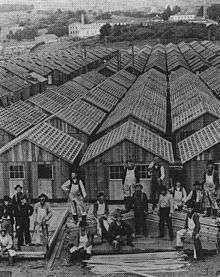

Balloon framing

Balloon framing originated in the American Mid-west near Chicago in the 1830s. It is a rare type of American historic carpentry which was exported from America. Balloon framing is very important in history as the beginning of the transition away from the centuries-long method of timber framing to the common types of wood framing now in use.

Corner post construction

Corner post construction is known by many names listed below, but particularly as pièce sur pièce and it blurs the line between timber framing and log building. This type of carpentry has a frame with horizontal beams or logs tenoned into slots or mortises in the posts. Pièce sur pièce en coulisse: Literally piece on piece in a groove is a widespread type of carpentry which blurs the lines between log, plankwall and framing techniques, thus is classified as any of the above. "The support of horizontal timbers by corner posts is an old form of construction in Europe. It was apparently carried across much of the continent from Silesia by the Lausitz urnfield culture in the late Bronze Age."[5] Examples also persist in southern Sweden, in the Alps, Hungry, Poland, Denmark, and Canada. Usually the origin of corner post construction is credited to the immigrants of the far-Eastern French in Canada and Alpine-Alemannic Germans or Swiss in the U. S.[6] This technique is best known in German as standerbohlenbau or bohlenstanderbau.

Horizontal wood pieces (poles, beams, planks) tenoned into grooves in posts. This type of construction allows shorter timbers to be used and a building can be extended an indefinite length by adding more bays, typically measuring ten feet. Similar methods of construction are found in most if not all Viking settled regions and was common in Scandinavia. It is one of the earliest building types of French-Canada used extensively by the Hudson's Bay Company for trading posts across Canada. It became a common, widespread building method in Canada. Other French names reflect the shape of wood (bois) used between the posts such as planche en coulisse, madriers-, or pieux-. Also recorded in French as bois en coulisse, poteaux en coulisse, madriers en coulisse, poteaux entourées de pieux, charpente entourée de madriers, poteaux entourées de madriers, en poteaux et close de pieux, en pieux sur pieux. (Lessard and Vilandré 1974:117) and “piece-sur-piece de charpente“ (French Canadian). Piece sur piece literally means piece on piece and also describes log building with notched corners or any kind of stacked construction.

Used in the United States predominantly in early French forts and settlements along the Mississippi River, though examples also occur in other states including Maine, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Ohio, Wyoming, Maryland, and Michigan where the it is the construction method of oldest house in the state (Navarre-Anderson Trading Post, 1789). A particularly interesting example is the Golden Plough Tavern (c. 1741), York, York County, PA, which has the ground level of corner-post construction, the second floor of fachwerk (half timbered) and was built for a German with other Germanic features[7]

"This sophisticated system, which uses carefully constructed mortise-and-tenon joints, was common from the 1820s to the 1860s and represents some 5 percent of the log houses built in western Maryland.”[8] Occasionally these buildings have earthfast posts. James Hébert incorrectly presented it as “an entirely Canadian style".[9] Also known other parts of central Europe, Medieval British Isles, including (Switzerland, Austria and S. Germany),. The Norman French were credited with the introduction of this building technique to Canada, though this technique is found in northwest Europe, the Alps to Hungry. It was used in Pennsylvania and North Carolina by German immigrants.

There are many names for corner post construction in many languages:

- French: Pièce sur pièce poteaux et pièce coulissante (piece on piece sliding in a groove) Pièce sur pièce en coulisse, poteaux et piece coulissante, pieces sur pieces,

- German, (Southern Germany, Switzerland, Austria): blockstanderbau, standerblockbau, ständerbohlenbau (post plank construction), bohlenständerbau (plank post construction)

- Polish: sumikowo-latkowej (planks sumiki, sumikami, palcami, post latki)

- English: Corner-post log construction, corner post construction, corner posting technique, post cornering, vertical-post log construction, post and log, post and panel, Red River frame, Hudson's Bay style, Hudson's Bay corners, Rocky Mountain frame, Manitoba Frame, “Métis” style, the “French” style, slotted post construction, panel construction, section panel, running mortise and tenon (or tongue)

- Swedish: Sleppvegg (slip wall?), skiftesverk (shift work)

- Danish: bulhus (bole house which means plank house)

- Spanish: a ritti e panconi

An example of corner post construction is the Cray House in Stevensville, Maryland.

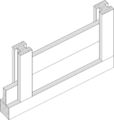

Plank-frame houses

Plank-frame house construction has a timber frame with the walls made of vertical planks attached to the frame. These houses may simply be called plank houses. Some building historians prefer the term plank-on-frame. Plank-frame houses are known from the 17th century with concentrations in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. The carpentry consists of a timber frame with vertical planks extending from sill to plate. Sometimes there are studs at the doors but mostly the vertical planks replace the studs. Both wood shingle or clapboard exterior siding and interior lath and plaster attach directly to the planks.[10] Some examples of plank frame houses are the oldest house in New Hampshire, the Richard Jackson House, Thomas and Esther Smith House in Massachusetts.

Palisade construction

A palisade is a series of vertical pales (stakes) driven or set into the ground to form a fence or barrier. Palisade construction is a palisade or the similar use of timbers set on a sill; an example in England being the original portion of the ancient Greensted Church and the early type of stave church known as a palisade church. It was common for Native Americans and Europeans to build a palisade as part of a fort or to protect a village. Palisade construction is alluded to as a method of building of early dwellings.[11] The nature of planting one end of a timber in the ground is called earthfast or post in ground construction which was a common way to build worldwide. A benefit of earthfast construction is the ground holds the posts from swaying which eliminates the need for bracing and anchors the structure to the ground. The French settlers called this carpentry en pieux or poteaux en terre[12] and log on end.[13] This type of carpentry may not considered framing. The French method of poteaux en terre was different than palisade construction in that the timbers were hewn two sides and spaced slightly apart with the gaps filled with a material called bousillage[12]

Palisade construction is similar in concept to vertical plank wall construction.

Vertical Plank wall

Vertical plank wall buildings are sometimes also called plank houses. In Australia houses with vertical plank walls are called slab huts and the technique is similar to the American counterpart except in America these buildings may be two stories.

Some plank-wall houses or creole cottages in the New Orleans area are called bargeboard[14] or flatboat board[15] houses because the vertical planks used to build the walls were reused planks from barges (flatboats) floated down the Mississippi River loaded with cargo and then broken up and the lumber sold. (Note the possibility of confusion with the different carpentry element called a bargeboard).

Stacked plank and stacked board construction

Another carpentry method which is sometimes called plank wall, board wall, plank-on-plank, horizontal plank frame is the stacking of horizontal planks or boards to form a wall of solid lumber. Sometimes the planks were staggered or spaced apart to form keys for a coat of plaster. This method was recommended by Orson Squire Fowler for octagon houses in his book The Octagon House: A Home for All in 1848.[10] Fowler mentions he had seen this wall type being built in central New York state while traveling in 1842.

Box houses

Box houses (boxed house, box frame,[16] box and strip,[17] piano box, single-wall, board and batten, and many other names) have minimal framing in the corners and widely spaced in the exterior walls, but like the vertical plank wall houses, the vertical boards are structural.[18] The origins of boxed construction is unknown. The term box-frame was used in a reconstruction manual in 1868 after the American Civil War.[19]

Box house may also be a nickname for Classic Box or American Foursquare architectural styles in North America, and is also not to be confused with a general type of timber framing called a box frame.

A variation on boxed construction is used on the Wesleyan Grove cottage: cottages around Oak Bluffs (Cottage City), Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts, are built of vertical, tongue and groove planks without battens usually in a gothic style. This method was “inspired by the tent frame construction”[20] of the original "board tents" used for Methodist Camp Meetings beginning in 1835.

A-frame buildings

An A-frame building has framing with little or no walls, the rafters join at the ridge forming an A shape. This is the simplest type of framing but has historically been used for inexpensive cottages and farm shelters until the A-frame house was popularized in the 1950s as a style of vacation home in the United States.

Inside-out framing

Inside-out framing has the sheathing boards or planks on the inside of the framing.[21] This type of structure was used for structures intended to contain bulk materials like ore, grain or coal.

Plank-framed barns

Plank-framed barns[22] are different than a plank-framed house. Plank framed barns developed in the American Mid-West, such as the patente in 1876 (#185,690) by William Morris and Joseph Slanser of La Rue, Ohio, shows (several other patents followed). Sometimes they were also called a joist frame, rib frame and trussed frame barns. Built of a “Construction in which none of the material used is larger than 2 inches thick.”[23] rather than solid timbers. The reduction in availability of timber for barn building and experience with scantling framing resulted in the development of this lightweight barn framing using planks (“joists”) rather than timbers. Some stated advantages: cheaper, faster, no interior posts needed, use any length lumber, less skill, less lumber (either purchased or self-produced), “stronger”, lighter, all lumber can be purchased from a lumber yard, less labor, heavy timber getting scarce. Also, they were often similar to the Jennings barn design of 1879 (patent #218,031) with no tie beam so there were no beams to interfere with a hay fork (horse fork) on a track system (hay carrier) for pitching hay which became popular c. 1877. The gambrel roof shape lends itself to plank truss construction and became the most popular roof type. Plank frame barns were available by mail-order by 1910 from Chicago. Syn joist-frame, Shawver plank-frame and Wing plank-frame. “In large construction, such as barn framing, there are two general systems, the braced, pin-joint frame, made of heavy timbers, and the plank frame, made up of two inch planking, either in the form of the ‘plank truss’ or the ‘balloon frame.’” (Architectural Drawing and Design of Farm Structures, 1915)

Types of structural roof carpentry

Timber roof trusses

Plank framed trusses

Plank framed truss was the name for roof trusses made with planks rather than timber roof trusses. In the 20th century it was typical for carpenters to make their own trusses by nailing planks together with wood plates at the joints. Today similar trusses are manufactured to engineering standards and use truss connector plates.

Types of structural floor carpentry

Single and double floor timber framing

In timber framing a single floor is a floor framed with single set of joists. A double floor is generally used for longer spans and joists, called bridging beams or joists, are supported by other beams called binding beams: the two layers of timbers providing the name double floor. In a double floor there may be two sets of joists, one for the floor above and one for the ceiling below.

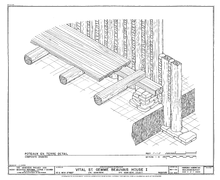

Plank and beam construction

Plank and beam construction or framing is a type of framing with no joists but widely spaced beams spanned by heavy planks. This method developed in the early 19th century for industrial mill floors but may also be found in timber framed roofs. Also known as Slow burning construction, mill construction, and heavy timber construction originated in industrial mills in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The joists are eliminated by the use of heavy planks saving time and strength of the timbers because the joists notches were eliminated. The beams are spaced 4 feet (1.2 m) to 18 feet (5.5 m) apart and the planks are 2 inches (5.1 cm) or more thick possibly with another layer of 1 inch (2.5 cm) on the top as the finished flooring could span these distances. The planks may be laid flat and tongue and grooved or splined together or laid on edge called a laminated floor.[24] The name slow burning construction was coined in 1870[25] by Factory Mutual insurance company[26] because large, smooth timbers with chamfered edges ignite slower and last longer in a fire allowing fire suppression crews more time to extinguish a fire. These beams are designed to be self-releasing in case of fire, that is if they burn through and collapse the connection with the masonry wall and joint at the post should allow the beam to fall away without pulling the wall or post down.[24] A common way to join a beam and a masonry wall in this regard is a fire cut, an angled cut on the end of the beam.[27]

Wooden bridges

.jpg)

A timber bridge or wooden bridge is a bridge that uses timber or wood as its principal structural material. One of the first forms of bridge, those of timber have been used since ancient times. Wooden bridges could a deck only structure or a deck with a roof. Wooden bridges were often a single span, but could be of multiple spans. A trestle bridge is a bridge composed of a number of short spans. Each supporting frame is a bent. Timber and iron trestles (i.e. bridges) were extensively used in the 19th century.[28] A covered bridge is a timber-truss bridge with a roof, decking, and siding, which creates a nearly complete enclosure.[29] The purpose of the covering is to protect the wooden structural members from the weather. Uncovered wooden bridges typically have a lifespan of only 20 years because of the effects of rain and sun, but a covered bridge could last 100 years.[30]

Other wooden structures

Other wooden structures do not necessarily have names for types of carpentry, but deserve mention. Carpenters were needed to build a variety of durable or temporary wooden structures such as a falsework and many other non-building structures.

Traditional carpentry tools

Square, saw, hammer, and a rule are the essentials for any carpenter old or new.

Education and organizations

See also

References

- Noble, Allen George. Traditional buildings a global survey of structural forms and cultural functions. London: I.B. Tauris, 2007. 7. Print.

- Hawkins, Reginald R., and Charles H. Abbe. New houses from old: a guide to the planning and practice of house remodeling.. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1948. Print.

- "Information and Direction to Such Persons as are Inclined to America, more Especially Those Related to the Province of Pennsylvania", reprinted in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography Vol. IV. 1880. Philadelphia. The Pennsylvania Historical Society. 329-342. Print.

- OLDEST - Log House in North America - Superlatives on Waymarking.com

- Dell Upton, John Michael Vlach. Common places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture, referencing V. Gordon Childe, The Bronze Age, NY, Macmillan, 1930, pp. 206-8

- Jordan, Terry. "Alpine, Alemannic, and American Log Architecture", Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 70(1980), pp. 154-80

- Nancy S. Shedd. “Corner-Post Log Construction: Description, Analysis, and Sources” Archived 2013-09-25 at the Wayback Machine, A Report to Early American Industries Association. March 10, 1986, and updated 2011. A very interesting report discussing numerous examples found in PA, some examples with the rare feature of bracing which is also found in MD and Poland.

- Gordon Bock and Douglass C. Reed, “Repairing a Historic Log Cabin: A variety of materials and methods work together in the structural repair of an 1850s log cabin”, Old House Journal, March/April 2001

- "Culture built upon the land : a predictive model of nineteenth-century Canadien/Métis farmsteads." Archived April 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Oregon State University Thesis 2007

- Garvin, James L.. A building history of northern New England. Hanover: University Press of New England, 2001. 21. Print.

- Kimball, Fiske. Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the Early Republic. New York: Dover Publications, 1966. 7. Print. quoting S. Smith. History of New Jersey 1765 and "The disposition of George Dunbar...", A state of the province of Georgia; attested upon oath in the Court of Savannah November 10, 1740. 7. print.

- Whiffen, Marcus, and Frederick Koeper. American Architecture. Volume 1: 1607-1860. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1983. 25. Print.

- Dwyer, Charles P. The Economic Cottage Builder: Or, Cottages for Men of Small Means. Buffalo: Wanzer, McKim, 1856. Print.

- "New Orleans Bargeboard", a blog with several interior photos showing the vertical plank walls

- Wilson, Samuel, Roulhac Toledano, and Sally Kittredge Evans. New Orleans architecture, volume IV: the Creole faubourgs. Gretna, La.: Pelican Pub. Co., 1974. 42. Print.

- Stephen B. Jordan. "Houses Without Frames: The Uncommon Technique of Plank Construction", Old House Journal vol XXI, n. 3. May/June 1993. 36-41. Print.

- Willard B. Robinson, "BOX AND STRIP CONSTRUCTION," Handbook of Texas Online (https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/cbb01), accessed April 15, 2014. Uploaded on June 12, 2010. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

- Noble, Allen George. Traditional buildings a global survey of structural forms and cultural functions. London: I.B. Tauris, 2007. Print.

- C. Thurston Chase. A Manual on School-houses and Cottages for the People of the South. 1868. Washington: Government Printing Office. 26-28. Print.

- Weiss, Ellen. City in the woods: the life and design of an American camp meeting on Martha's Vineyard. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. Print.

- Vlach, John Michael. Barns. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.;, 2003. 338. Print.

- Radford, William A., and Alfred S. Johnson. Framing; a practical manual of approved up-to-date methods of house framing and construction, together with tested methods of heavy timber and plank framing as used in the construction of barns, factories, stores, and public buildings; strength of timbers; and principles of roof and bridge trusses.. Chicago, Ill.: The Radford architectural Co., 1909. Print.

- Carter, Deane G., and W. A. Foster. Farm buildings. 3. ed. New York: Whiley and Sons, 1948. Print.

- Dewell, Henry Dievendorf. Timber framing. San Francisco: Dewey Pub. Co., 1917. 207. Print.

- Bradley, Betsy H.. The works: the industrial architecture of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. 127. Print.

- Randolph Langenbach "Better than Steel? (Part 2): Tall Wooden Factories and the Invention of “Slow-burning” Heavy Timber Construction"

- Brannigan, Francis L., and Glenn P. Corbett. Brannigan's building construction for the fire service. 4th ed. Sudbury, MA: National Fire Protection Association :, 2007. Print.

- Walter Loring Webb, Railroad Construction -- Theory and Practice, 6th Ed., Wiley, New York, 1917; Chapter IV -- Trestles, pages 194-226

- "Covered bridge". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- "Ohio's Vanishing Covered Bridges". Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved 8 January 2019.