American ginseng

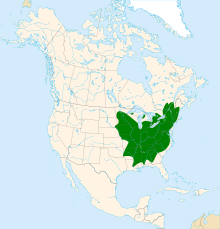

American Ginseng (Panax quinquefolius, Panacis quinquefolis) is a herbaceous perennial plant in the ivy family, commonly used as Chinese or traditional medicine. It is native to eastern North America, though it is also cultivated in China.[3][4] Since the 18th century, American ginseng (P. quinquefolius) has been primarily exported to Asia, where it is highly valued for its cooling and sedative medicinal effects. It is considered to represent the cooling yin qualities, while Asian ginseng embodies the warmer aspects of yang.[5]

| American ginseng | |

|---|---|

| |

| Panax quinquefolius[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. quinquefolius |

| Binomial name | |

| Panax quinquefolius | |

Description

The aromatic root of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) resembles a small parsnip that forks as it matures. The plant grows 6" to 18" tall, usually bearing three leaves, each with three to five leaflets, 2" to 5" long.

American Ginseng can be found in much of the eastern and central United States and in part of southeastern Canada.[6] It is found primarily in deciduous forests of the Appalachian and Ozark regions of the United States.[7] American ginseng is found in full shade environments in these deciduous forests underneath hardwoods.[8] Due to this very specialized growing environment and its demand in the commercial market it has started to reach an endangered status in some areas. It can be found throughout eastern Canada and the northeastern United States.[9]

In the United States, American ginseng is generally not listed as an endangered species, but it has been declared as a part of the endangered species scale by some states. States recognizing American ginseng as endangered: Maine, Rhode Island. States recognizing American ginseng as vulnerable: New York, Pennsylvania. States recognizing American ginseng as threatened: Michigan, New Hampshire, Virginia. States recognizing American ginseng as a special concern: Connecticut,[10] Massachusetts, North Carolina, Tennessee.[6]

Chemical components

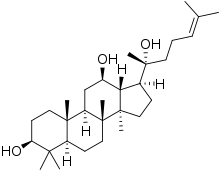

Like Panax ginseng, American ginseng contains dammarane-type ginsenosides, or saponins, as the major biologically active constituents. Dammarane-type ginsenosides include two classifications: 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (PPD) and 20(S)-protopanaxatriol (PPT). American ginseng contains high levels of Rb1, Rd (PPD classification), and Re (PPT classification) ginsenosides—higher than that of P. ginseng in one study.[11]

When taken orally, PPD-type ginsenosides are mostly metabolized by intestinal bacteria (anaerobes) to PPD monoglucoside, 20-O-beta-D-glucopyranosyl-20(S)-protopanaxadiol (M1).[12] In humans, M1 is detected in plasma starting seven hours after intake of PPD-type ginsenosides and in urine starting 12 hours after intake. These findings indicate M1 is the final metabolite of PPD-type ginsenosides.[13]

M1 is referred to in some articles as IH-901,[14] and in others as compound-K.[13]

Traditional medicine

The plant's root and leaves were used in traditional medicine by Native Americans. Since the 18th century, the roots have been collected by "sang hunters" and sold to Chinese or Hong Kong traders, who often pay high prices for particularly old wild roots.[15] Originally, American ginseng was imported into China via subtropical Guangzhou, the seaport next to Hong Kong. Since American ginseng was originally imported into China via a subtropical seaport, Chinese doctors believed American ginseng must be good for yin, because it came from a hot area. They did not know, however, that American ginseng can only grow in temperate regions. Nonetheless, the root is legitimately classified as more yin because it generates fluids.[16]

There is no evidence that American ginseng is effective against the common cold[17][18] or how severe the infections are.[18] There is tentative evidence that it may lessen the length of sickness when used preventively.[18]

Cold-fX is a product derived from the roots of North American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius). The makers of Cold-fX were criticized for making health claims about the product that have never been tested or verified scientifically. Health Canada's review of the scientific literature confirmed that this is not a claim that the manufacturer is entitled to make.[19]

Adverse effects

Individuals requiring anticoagulant therapy such as warfarin should avoid use of ginseng.[17] It is not recommended for individuals with impaired liver or renal function, or during pregnancy or breastfeeding.[17] Other adverse effects include: headaches, anxiety, trouble sleeping and an upset stomach.[17]

Recent studies have shown that through the many cultivated procedures that American ginseng is grown, fungal molds, pesticides, and various metals and residues have contaminated the crop. Though these contaminating effects are not considerably substantial, they do pose health concerns that could lead to neurological problems, intoxication, cardiovascular disease and cancer.[20]

Production

American ginseng was formerly particularly widespread in the Appalachian and Ozark regions (and adjacent forested regions such as Pennsylvania, New York and Ontario). Due to its popularity and unique habitat requirements, the wild plant has been overharvested, as well as lost through destruction of its habitat, and is thus rare in most parts of the United States and Canada.[21] Ginseng is also negatively affected by deer browsing, urbanization, and habitat fragmentation.[22] It can be grown commercially, under artificial shade, woods-cultivated, or wild-simulated methods, and is usually harvested after three to four years, depending on cultivation technique; the wild-simulated method often requires up to 10 years before harvest.

Ontario, Canada is the world's largest producer of North American ginseng.[23][24] Marathon County, Wisconsin, accounts for about 95% of production in the United States.[25] Woods-grown American ginseng programs in Vermont, Maine, Tennessee, Virginia, North Carolina, Colorado, West Virginia, and Kentucky,[26] have been encouraging the planting of ginseng both to restore natural habitats and to remove pressure from any remaining wild ginseng.

Names

The name ginseng derives from the Chinese herbalism term, jen-shen.[27] Other Chinese names are huaqishen (simplified Chinese: 花旗参; traditional Chinese: 花旗參; pinyin: huāqíshēn; Cantonese Yale: fākèihsām; lit.: 'Flower Flag ginseng') or xiyangshen (simplified Chinese: 西洋参; traditional Chinese: 西洋參; pinyin: xīyángshēn; Cantonese Yale: sāiyèuhngsām; lit.: 'west ocean ginseng').

Conservation status

American ginseng is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species to control international trade.[28]

Gallery

American ginseng in human figure.

American ginseng in human figure. Under wooden shade, American ginseng in late fall at Monk Garden in Wisconsin

Under wooden shade, American ginseng in late fall at Monk Garden in Wisconsin A picture of the American Ginseng plant with fruit.

A picture of the American Ginseng plant with fruit. American ginseng berries are ripe by late fall in Wisconsin.

American ginseng berries are ripe by late fall in Wisconsin. A drawn image of the fruit and leaf of the American Ginseng plant.

A drawn image of the fruit and leaf of the American Ginseng plant. A drawn image of the American ginseng plants leaves.

A drawn image of the American ginseng plants leaves. American wild ginseng root (Panax quinquefolius). This is a very old specimen, showing over 60 growth scars.

American wild ginseng root (Panax quinquefolius). This is a very old specimen, showing over 60 growth scars. American wild ginseng root (Panax quinquefolius). Very old roots, ranging from 40–60 growth scars.

American wild ginseng root (Panax quinquefolius). Very old roots, ranging from 40–60 growth scars. American wild ginseng root (Panax quinquefolius). This is a very old specimen, showing over 60 growth scars.

American wild ginseng root (Panax quinquefolius). This is a very old specimen, showing over 60 growth scars. American wild ginseng root (Panax quinquefolius). Very old roots, ranging from 40–65 growth scars.

American wild ginseng root (Panax quinquefolius). Very old roots, ranging from 40–65 growth scars.

References

- Panax_quinquefolius L., from "American medical botany being a collection of the native medicinal plants of the United States, containing their botanical history and chemical analysis, and properties and uses in medicine, diet and the arts" by Jacob Bigelow,1786/7-1879. Publication in Boston by Cummings and Hilliard,1817-1820.

- "Panax quinquefolius". NatureServe Explorer. NatureServe. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- Xiang, Q.; Lowry, P. P. (2007). "Araliaceae". In Wu, Z. Y.; Raven, P. H.; Hong, D. Y. (eds.). Flora of China (pdf). 13. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Botanical Garden Press. p. 491. ISBN 9781930723597.

- "Panax quinquefolius". eFloras.

- "History of Ginseng". Ontario Ginseng Growers Association. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- U.S. Government, USDA. "Panax quinquefolius L." Plants Database. USDA. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- U.S. Government, Fish and Wildlife Service. "American Ginseng". International Affairs. United States Fish and Wildlife Services. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Anderson, Kat. "American Ginseng" (PDF). Plant Guide. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "Taxon: Pana quinquefolius L." National Plant Germplasm System. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "Connecticut's Endangered, Threatened and Special Concern Species 2015". State of Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Bureau of Natural Resources. Retrieved 31 December 2017. (Note: This list is newer and updated from the one used by plants.usda.gov)

- Zhu, S.; Zou, K.; Fushimi, H.; Cai, S.; Komatsu, K. (2004). "Comparative study on triterpene saponins of ginseng drugs". Planta Medica. 70 (7): 666–677. doi:10.1055/s-2004-827192. PMID 15303259.

- Hasegawa, H.; Sung, J.-H.; Matsumiya, S.; Uchiyama, M. (1996). "Main ginseng saponin metabolites formed by intestinal bacteria". Planta Medica. 62 (5): 453–457. doi:10.1055/s-2006-957938. PMID 8923812.

- Tawab, M. A.; Bahr, U.; Karas, M.; Wurglics, M.; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M. (2003). "Degradation of ginsenosides in humans after oral administration". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 31 (8): 1065–1071. doi:10.1124/dmd.31.8.1065. PMID 12867496.

- Oh, S.-H.; Lee, B.-H. (2004). "A ginseng saponin metabolite-induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells involves a mitochondria-mediated pathway and its downstream caspase-8 activation and Bid cleavage". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 194 (3): 221–229. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2003.09.011. PMID 14761678.

- There is More to a Forest than Trees. research.vt.edu (Summer 2002)

- Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, Third Edition by Dan Bensky, Steven Clavey, Erich Stonger, and Andrew Gamble 2004

- "Asian ginseng". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. September 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Seida, JK; Durec, T; Kuhle, S (2011). "North American (Panax quinquefolius) and Asian Ginseng (Panax ginseng) Preparations for Prevention of the Common Cold in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011: 282151. doi:10.1093/ecam/nep068. PMC 3136130. PMID 19592479.

- Charlie Gillis (2007-03-26). "COLD-fX catches the sniffles again". Maclean's Magazine. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07.

- Wang, Zengui; Huang, Linfang (March 2015). "Panax quinquefolius: An overview of the contaminants". Phytochemistry Letters. 11: 89–94. doi:10.1016/j.phytol.2014.11.013.

- Beattie-Moss, M. (2006-06-19). "Roots and Regulations - The unfolding story of Pennsylvania ginseng". Pennstate news.

- McGraw, J. "Population Biology and Conservation Ecology of American Ginseng". West Virginia University.

- "Canadian Ginseng - It is in our Roots". Ontario Ginseng Growers Association. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- Recovery Strategy for American Ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) in Canada - 2015 (Proposed). Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series (Report). Environment Canada. 17 April 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Ginseng Prices at Highest in Decades". The Post Crescent. October 19, 2010.

- "Ginseng program". Kentucky Agriculture Department. 2017. Archived from the original on 2010-06-26. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- "Ginseng". Online Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper. 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- "Appendices I, II and III". Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. 2010-10-14. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Panax quinquefolius |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panax quinquefolius. |

- "Roots and Regulations: The Unfolding Story of Pennsylvania Ginseng", by Melissa Beattie-Moss