Ambush

An ambush is a long-established military tactic in which combatants take advantage of concealment and the element of surprise to attack unsuspecting enemy combatants from concealed positions, such as among dense underbrush or behind hilltops. Ambushes have been used consistently throughout history, from ancient to modern warfare. In the 20th century, an ambush might involve thousands of soldiers on a large scale, such as over a choke point such as a mountain pass, or a small irregular band or insurgent group attacking a regular armed force patrol. Theoretically, a single well-armed and concealed soldier could ambush other troops in a surprise attack. Sometimes an ambush can involve the exclusive or combined use of improvised explosive devices, that allow the attackers to hit enemy convoys or patrols while minimizing the risk of being exposed to return fire.[1][2]

History

The use by early humans of the ambush may date as far back as two million years when anthropologists have recently suggested that ambush techniques were used to hunt large game.[3]

One example from ancient times is the Battle of the Trebia river. Hannibal encamped within striking distance of the Romans with the Trebia River between them, and placed a strong force of cavalry and infantry in concealment, near the battle zone. He had noticed, says Polybius, a "place between the two camps, flat indeed and treeless, but well adapted for an ambuscade, as it was traversed by a water-course with steep banks, densely overgrown with brambles and other thorny plants, and here he proposed to lay a stratagem to surprise the enemy". When the Roman infantry became entangled in combat with his army, the hidden ambush force attacked the legionnaires in the rear. The result was slaughter and defeat for the Romans. Nevertheless, the battle also displays the effects of good tactical discipline on the part of the ambushed force. Although most of the legions were lost, about 10,000 Romans cut their way through to safety, maintaining unit cohesion. This ability to maintain discipline and break out or maneuver away from a kill zone is a hallmark of good troops and training in any ambush situation. (See Ranger reference below).

Ambushes were widely utilized by the Lusitanians, in particular by their chieftain Viriathus. Their usual tactic, called concursare, involved repeatedly charging and retreating, forcing the enemy to eventually give them chase, in order to set up ambushes in difficult terrain where allied forces would be awaiting. In his first victory, he eluded the siege of Roman praetor Gaius Vetilius and attracted him to a narrow pass next to the Barbesuda river, where he destroyed his army and killed the praetor. Viriathus's ability to turn chases into ambushes would grant him victories over a number of Roman generals. Another famous Lusitanian ambush was performed by Curius and Apuleius on Roman general Quintus Fabius Maximus Servilianus, who led a numerically superior army complete with war elephants and Numidian cavalry. The ambush allowed Curius and Apuleius to steal Servilianus's loot train, although a tactic error in their retreat led to the Romans retaking the train and putting the Lusitanians to flight. Viriathus later defeated Servilianus with a surprise attack.[4]

Possibly the most famous ambush in ancient warfare was that sprung by Germanic warchief Arminius against the Romans at Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. This particular ambush was to affect the course of Western history. The Germanic forces demonstrated several principles needed for a successful ambush. They took cover in difficult forested terrain, allowing the warriors time and space to mass without detection. They had the element of surprise, and this was also aided by the defection of Arminius from Roman ranks prior to the battle. They sprang the attack when the Romans were most vulnerable; when they had left their fortified camp, and were on the march in a pounding rainstorm.

The Germans did not dawdle at the hour of decision but attacked quickly, using a massive series of short, rapid, vicious charges against the length of the whole Roman line, with charging units sometimes withdrawing to the forest to regroup while others took their place. The Germans also used blocking obstacles, erecting a trench and earthen wall to hinder Roman movement along the route of the killing zone. The result was mass slaughter of the Romans, and the destruction of three legions. The Germanic victory caused a limit on Roman expansion in the West. Ultimately, it established the Rhine as the boundary of the Roman Empire for the next four hundred years, until the decline of the Roman influence in the West. The Roman Empire made no further concerted attempts to conquer Germania beyond the Rhine.

There are many notable examples of ambushes during the Roman-Persian Wars. A year after their victory at Carrhae, the Parthians invaded Syria but were driven back after a Roman ambush near Antigonia. Roman Emperor Julian was mortally wounded in an ambush near Samarra in 363 during the retreat from his Persian campaign. A Byzantine invasion of Persian Armenia was repelled by a small force at Anglon who performed a meticulous ambush by using the rough terrain as force multiplier and concealing in houses.[5] Heraclius' discovery of a planned ambush by Shahrbaraz in 622 was a decisive factor in his campaign.

Arabia during Muhammad's era

According to Muslim tradition, Islamic Prophet Muhammad used ambush tactics in his military campaigns. His first such use was during the Caravan raids, in the Kharrar caravan raid Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas was ordered to lead a raid against the Quraysh. His group consisted of about twenty Muhajirs. This raid was done about a month after the previous. Sa'd, with his soldiers, set up an ambush in the valley of Kharrar on the road to Mecca and waited to raid a returning Meccan caravan from Syria. But the caravan had already passed and the Muslims returned to Medina without any loot.[6][7]

Arab tribes during Muhammad's era also used ambush tactics. One example retold in Muslim tradition is said to have taken place during the First Raid on Banu Thalabah. The Banu Thalabah tribe were already aware of the impending attack; so they lay in wait for the Muslims, and when Muhammad ibn Maslama arrived at the site. The Banu Thalabah, with 100 men ambushed them, while the Muslims were making preparation to sleep; and after a brief resistance killed all of Muhammad ibn Maslama's men. Muhammad ibn Maslama pretended to be dead. A Muslim who happened to pass that way found him and assisted him to return to Medina. The raid was unsuccessful.[8]

Procedure

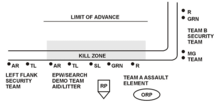

In modern warfare, an ambush is most often employed by ground troops up to platoon size against enemy targets, which may be other ground troops, or possibly vehicles. However, in some situations, especially when deep behind enemy lines, the actual attack will be carried out by a platoon, a company-sized unit will be deployed to support the attack group, setting up and maintaining a forward patrol harbour from which the attacking force will deploy, and to which they will retire after the attack.

Planning

Ambushes are complex multi-phase operations and are therefore usually planned in some detail. First, a suitable killing zone is identified. This is the place where the ambush will be laid. It is generally a place where enemy units are expected to pass, and which gives reasonable cover for the deployment, execution and extraction phases of the ambush patrol. A path along a wooded valley floor would be a typical example.

Ambush can be described geometrically as:

- Linear, when a number of firing units are equally distant from the linear kill zone.

- L-shaped, when a short leg of firing units are placed to enfilade (fire the length of) the sides of the linear kill zone.

- V-shaped, when the firing units are distant from the kill zone at the end where the enemy enters, so the firing units lay down bands of intersecting and interlocking fire. This ambush is normally triggered only when the enemy is well into the kill zone. The intersecting bands of fire prevent any attempt of moving out of the kill zone.[9]

Viet Cong ambush techniques

Ambush criteria: The terrain for the ambush had to meet strict criteria:

- provide concealment to prevent detection from the ground or air

- enable ambush force to deploy, encircle and divide the enemy

- allow for heavy weapons emplacements to provide sustained fire

- enable the ambush force to set up observation posts for early detection of the enemy

- permit the secret movement of troops to the ambush position and the dispersal of troops during withdrawal

One important feature of the ambush was that the target units should 'pile up' after being attacked, thus preventing them any easy means of withdrawal from the kill zone and hindering their use of heavy weapons and supporting fire. Terrain was usually selected which would facilitate this and slow down the enemy. Any terrain around the ambush site which was not favorable to the ambushing force, or which offered some protection to the target, was heavily mined and booby trapped or pre-registered for mortars.

Ambush units: The NVA/VC ambush formations consisted of:

- lead-blocking element

- main-assault element

- rear-blocking element

- observation posts

- command post

Other elements might also be included if the situation demanded, such as a sniper screen along a nearby avenue of approach to delay enemy reinforcements.

Command posts: When deploying into an ambush site, the NVA first occupied several observation posts, placed to detect the enemy as early as possible and to report on the formation it was using, its strength and firepower, as well as to provide early warning to the unit commander. Usually one main OP and several secondary OP's were established. Runners and occasionally radios were used to communicate between the OP's and the main command post. The OP's were located so that they could observe enemy movement into the ambush and often they would remain in position throughout the ambush in order to report routes of reinforcement and withdrawal by the enemy as well as his maneuver options. Frequently the OP's were reinforced to squad size and served as flank security. The command post was situated in a central location, often on terrain which afforded it a vantage point overlooking the ambush site.

Recon methods: Reconnaissance elements observing a potential ambush target on the move generally stayed 300–500 meters away. Sometimes a "leapfrogging" recon technique was used. Surveillance units were echeloned one behind the other. As the enemy drew close to the first, it fell back behind the last recon team, leaving an advance group in its place. This one in turn fell back as the enemy again closed the gap, and the cycle rotated. This method helped keep the enemy under continuous observation from a variety of vantage points, and allowed the recon groups to cover one another.[11]

See also

- Ambush predator

- Viet Cong and PAVN battle tactics

- Flanking maneuver

- Flypaper theory (strategy)

- List of military tactics

- Sniper

References

- Armor. U.S. Armor Association. 2004.

- "The improvised explosive solution - msnbc". www.nbcnews.com. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- Bunn, Henry T.; Alia N. Gurtov (February 16, 2014). "Prey Mortality Profiles Indicate That Early Pleistocene Homo at Olduvai Was an Ambush Predator". Quaternary International. 322–323: 44–53. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.11.002.

- Benjamín Collado Hinarejos (2018). Guerreros de Iberia: La guerra antigua en la península Ibérica (in Spanish). La Esfera de los Libros. ISBN 978-84-916437-9-1.

- Bury, John Bagnell (1889). A History of the Later Roman Empire: From Arcadius to Irene (395 A.D. to 800 A.D.). Macmillan and Company. p. 436.

- Mubarakpuri, The Sealed Nectar (Free Version), p. 127.

- Haykal, Husayn (1976), The Life of Muhammad, Islamic Book Trust, pp. 217–218, ISBN 978-983-9154-17-7

- Mubarakpuri, Saifur Rahman Al (2005), The Sealed Nectar, Darussalam Publications, p. 205

- FM 7-85 Chapter 6 Special Light Infantry Operations

- Terrence Maitland, A CONTAGION OF WAR: THE VIETNAM EXPERIENCE SERIES, (Boston Publishing Company), 1983, p. 180

- RAND Corp, "Insurgent Organization and Operations: A Case Study of the Viet Cong in the Delta, 1964–1966", (Santa Monica: August 1967)

- Extract from Lt Col Anthony B. Herbert's Soldiers handbook

- US Army Ranger Handbook section 5-14 for ambushes and 6-11 for reaction to ambushes