Amadou Bamba

Ahmadou Bamba Mbacke (Wolof: Ahmadu Bamba Mbacke, Arabic: أحمد بن محمد بن حبيب الله Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Ḥabīb Allāh, 1853–1927)[1] also known to followers as Khādimu 'al-Rasūl (خادِم الرسول) or "The Servant of the Messenger" and Serigne Touba or "Sheikh of Tuubaa", was a Sufi saint (Wali) and religious leader in Senegal and the founder of the large Mouride Brotherhood (the Muridiyya).

Mbacke produced poems and tracts on meditation, rituals, work, and Quranic study. He led a pacifist struggle against the French colonial empire while not waging outright war on the French like several prominent Tijani marabouts had done.

Early life

Ahmadou Bamba was born in 1853 in the village of Mbacké (Mbàkke Bawol in Wolof) in Baol, the son of Habibullah Bouso Mbacke, a Marabout from the Qadiriyya, the oldest tariqa (Sufi order) in Senegal, and Maryam Bousso.[2]

Family and genealogy

Bamba was the second son of Maam Mor Anta Saly Mbacke and Maam Mariyama Bousso. Both of his parents were descended from the well-known patriarch Maam Mahram Mbacke, with their ancestors hailing from Fouta, northern Senegal. The following list of ancestors, descendants, and companions of Sheikh Bamba has been adapted from Mbacke (2016).[3]

Ancestors:[3]

- Maam Mor Anta Saly Mbacke (father). His master was Muhammad Sall, who hailed from Bamba village.

- Mame Diarra Bousso (Mama Diaara Bousso) (mother). Her family came from Golléré, a village near Fouta and Mbacké. Today, Mama Diaara is celebrated annually by hundreds of thousands of pilgrims at Porokhane, where she remains buried.

- Maam Mor Anta Saly (Mama Diaara Bousso's father) was a highly respected Islamic scholar.

- Maam Balla Aicha (paternal grandfather). He was the youngest son of Maam Mahram.

- Maam Mahram Mbacke (paternal great-grandfather). He was both a well-known qadi and the founder of Mbacké.

Descendants:[3]

- Sheikh Bachir Mouhamadoul (son) was Amadou Bamba's biographer.

- Sheikh Mouhamadou Lamine Bara Mbacke (1891-1936). Third son.

- Serigne Sidi Moukhtar Mbacké (grandson). Seventh caliph of the Mouride Brotherhood. Son of Sheikh Mouhamadou Lamine Bara Mbacke.

- Sheikh Mouhamadoul Bachir (1895–1966). Fourth son.

- Serigne Moustapha Mbacke Bassirou (grandson). Eldest son of Sheikh Mouhamadoul Bachir. He modernized Porokhane village, founded the Maam Diaara foundation, and set up a girls' boarding school in Porokhane that can accommodate 400 students.

- Serigne Mouhamadou Moustapha Mbacké (son). First caliph of the Mouride Brotherhood.[4]

- Serigne Sheikh Gaindé Fatma (grandson, and also the first caliph's eldest son). Gaindé Fatma founded French-language and Arabic-language schools, provided scholarships, and was an important community figure who focused on advancing education in Senegal.

- Serigne Mouhamadou Fallilou Mbacké (son). Second caliph of the Mouride Brotherhood.[5]

- Serigne Abdou Ahad Mbacké (son). Third caliph of the Mouride Brotherhood.[6]

- Serigne Abdou Khadr Mbacké (son). Fourth caliph of the Mouride Brotherhood.[7]

- Serigne Saliou Mbacké (son). Fifth caliph of the Mouride Brotherhood, and the last surviving son of Bamba.

- Serigne Mouhamadou Lamine Bara Mbacké. Sixth caliph of the Mouride Brotherhood, and the nephew of the fifth caliph Serigne Saliou Mbacké.

Siblings:[3]

- Maam Mor Diarra, uterine brother. Today, he is revered by his city, Sahm.

- Maam Thierno Birahim Mbacke, younger brother. He took care of Bamba's family and community while he was exiled by French colonial authorities. Today, he is revered by his city, Darou Mousti.

- Maam Sheikh Anta Darou Salam, a Mouride businessman. Today, he is revered by his city, Darou Salam.

- Serigne Massamba. He copied Bamba's writings.

- Serigne Afe Mbacke

Other important people associated with Bamba:[3]

- Sheikh Mouhamadou Lamine Diop Dagana, Bamba's biographer and companion

- Serigne Dame Abdourahmane Lo, teacher of Bamba's children

- Sheikh Adama Gueye, the first Mouride follower

- Maam Sheikh Ibrahima Fall, founder of the Baye Fall community

Foundation of Mouridiyya and Touba

Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba founded the Mouride brotherhood in 1883, with its capital is Touba, Senegal. Today, Touba serves as the location of the sub-Saharan Africa's largest mosque, which was built by the Mourides.[8]

Ahmadou Bamba's teachings emphasized the virtues of pacifism, hard work and good manners through what is commonly known as Jihādu nafs which emphasizes a personal struggle over "negative instincts."[1] As an ascetic marabout who wrote tracts on meditation, rituals, work, and Quranic study, he is perhaps best known for his emphasis on work and industriousness.

Bamba's followers call him a mujaddid ("renewer of Islam"), citing a hadith that implies that God will send renewers of the faith every 100 years (the members of all the Senegalese brotherhoods claim that their founders were such renewers).

Abdoul Ahad Mbacke, the third Caliph (Mouride leader) and son of Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, declared that Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba had met the prophet Muhammad in his dreams, a tale that has become an article of faith for Mouride believers. During the month of Ramadan 1895, Muhammed and his companions appeared to him in a dream in Touba to confer upon him the rank of mujaddid of his age,[9] and to test his faith.[10] From this, Bamba is said to also have been conferred the rank of "Servant of the Prophet."[11]

He founded the city of Touba in 1887. In one of his numerous writings, Matlabul Fawzeyni (the quest for happiness in both worlds), Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba describes the purpose of the city, which was intended to reconcile the spiritual and the temporal.

Facing colonial rule and exile

As Bamba's fame and influence spread, the French colonial government worried about his growing power and potential to wage war against them. He had stirred "anti-colonial disobedience"[12] and even converted a number of traditional kings and their followers and no doubt could have raised a huge military force, as Muslim leaders like Umar Tall and Samory Touré had before him. During this time, the French army and French colonial government were weary of Muslim leaders inciting revolts as they finished taking over Senegal.[12]

The phobia of the colonial administration at the place of any Islamic movement made the judgements given to the Privy Council often constitute lawsuits of intention to religious leaders. Stopped in Diéwol, Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba was transferred to the office of the Governor of the colonial administration in Saint-Louis (Senegal). On Thursday September 5, 1895, he appeared before the Privy Council (Conseil d'Etat) of Saint-Louis to rule on his case. Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba prayed two rakat in the Governor's office before addressing the Council, declaring his firm intention to be subjected to God alone. With this symbolic prayer and stance in the sanctuary of the deniers of Islam, Bamba came to embody a new form of nonviolent resistance against the aims of colonial evangelists.[13] Proof of Bamba having recited these prayers is not included in colonial archives, but is rather based on the testimonies of his disciples.[12] As a result of Bamba's prayers, the Privy Council decided to deport him to "a place where its fanatic preachings would not have any effect".[13] and exiled him to the equatorial forest of Gabon, where he remained for seven years and nine months. While in Gabon, he composed prayers and poems celebrating Allah.

From the beginning of the 19th century, the imperialist policy of France ended with the defeat of all the armed resistance movements in Senegal and the installation of a policy of Christianization and assimilation of the new colony to the cultural values of the metropolis. This led to a policy of exile or systematic elimination of the Muslim spiritual guides who openly spoke out against the colonial government. Thus, Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, whose only alleged crime was persisting in preaching his religion(Islam), was subjected to all manner of deprivation and trials for 32 years. Exiled for seven years to Gabon and five years to Mauritania and placed under house arrest in Diourbel, Senegal for fifteen years, Ahmadou Bamba nevertheless did not cease to defend the message of Islam until his death in 1927.[13]

In the political sphere, Ahmadou Bamba led a pacifist struggle against French colonialism while trying to restore a purer practice of Islam insulated from French colonial influence. In a period when successful armed resistance was impossible, Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba led a spiritual struggle against colonial culture and politics. Although he did not wage outright war on them as several prominent Tijaan marabouts had done, he taught what he called the jihād al-'akbar or "greater struggle," which fought not through weapons but through learning and fear of God.

As Bamba gathered followers, he taught that salvation comes through complete submission to God and hard work. The Mouride order has built, following this teaching, a large economic organisation, involved in many aspects of the Senegalese economy. Groundnut cultivation, the primary cash crop of the colonial period, was an early example of this. Young followers were recruited to settle marginal lands in eastern Senegal, found communities and create groundnut plantations. With the organisation and supplies provided by the Brotherhood, a portion of the proceeds were returned to Touba, while the workers, after a period of years, earned ownership over the plantations and towns.

Fearing his influence, the French sentenced him to exile in Gabon (1895–1902) and later in Mauritania (1903–1907). However, these exiles inspired stories and folk tales of Bamba's miraculous survival of torture, deprivation, and attempted executions, and thousands more flocked to his organization.[14]

By 1910, the French realized that Bamba was not interested in waging violent war against them, and was in fact quite cooperative, eventually releasing him to return to his expanded community. In 1918, they rewarded him with the French Legion of Honor for enlisting his followers in the First World War: he refused it. They allowed him to establish his community in Touba, believing in part that his doctrine of hard work could be made to work with French economic interests.

His movement continued to grow, and in 1926 he began work for the great mosque at Touba.

Death

After his death in 1927, he was buried in Touba at a site he had chosen, adjacent to the future location of The Grand Mosque.[15] He was succeeded by his descendants as hereditary leaders of the brotherhood with absolute authority over the followers. Currently, Serigne Mountakha Mbacké is the Khalifa-General, Ahmadou Bamba's oldest living grandson who holds the brotherhood's highest office.[8]

Legacy

As the founder of Mouridism, Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba is considered one of the greatest spiritual leaders in Senegalese history and of the biggest influences on contemporary Senegalese life and culture. Mouridism is today one of Senegal’s four Sufi movements, with four million devotees in Senegal alone and thousands more abroad, the majority of whom are emigrants from Senegal. Followers of the Mouride movement, an offshoot of traditional Sufi philosophy, aspire to live closer to God, in emulation of the Prophet Muhammad's example. Today, Ahmadou Bamba has an estimated following of more than 3 million people and parades occur around the world in his honor, including in various cities in the USA.[16] One such city is New York, where Muslims of West African descent have organized an "annual Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba Day parade" for over twenty years. Celebrations like these create platforms to "redefine the boundaries of their African identities, cope with the stigma of blackness, and counteract an anti-Muslim backlash".[17]

Every year, millions of Muslims from all over the world make a pilgrimage to Touba (known as the Magal), worshipping at the mosque and honoring the memory of Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba.[18][19]

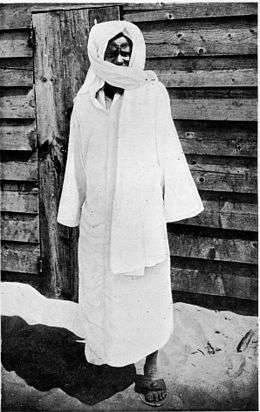

Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba has only one surviving photograph, in which he wears a flowing white robe and his face is mostly covered by a scarf. This picture is venerated and reproduced in paintings on walls, buses, taxis, etc. all over Senegal. This photo was originally taken in 1913 by "French colonial authorities".[20] As an art form and spiritual object, Bamba's photograph functions as more than a mere image, rather it is also "a living presence" through which his baraka flows.[21]

Modern Mourides contribute earnings to the brotherhood, which provides social services, loans, and business opportunities in return.[22]

Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba is also known to have invented Café Touba. Bamba traditionally mixed coffee and spices together for medicinal purposes, and served it to his followers.[23]

Senegalese musician Youssou N'Dour has claimed to be a follower of Mouridism. His 2004 Grammy-winning album Egypt features multiple songs that praise Bamba.[24]

Writings

Amadou Bamba is the author of various manuscripts, most of which are currently held at the library of the Great Mosque of Touba. Below is a selection of Bamba's writings:[25]

- Jawharu-n-nafis (The Precious Jewel)

- Mawâhibul quddûs (the Gifts of the Holy Lord)

- Jadhbatu-ç-çighâr (the Attraction of the Youth)

- Mulayyinu-ç-çudûr (The Softening of the Hearts)

- Jaawartu Lâh (Allah’s Neighborhood)

- Khâtimatu Munajât (The Ultimate Dialogue)

- Masâalik Al Jinân (The Itineraries to Paradise)

- Huqal Buka-u (Is it necessary to cry for the dead Sufi masters?)

- Munawwiru-ç-Cudûr (The Illumination of the Hearts)

- Maghâliqu-n-Nîrân wa Mafâtihul Jinân (The Locks of Hell and The Keys to Paradise)

- Tazawwudu-sh-Shubbân (Provisions of the Youth)

Poems honoring the Prophet Muhammad:

- Muqadimmatul Amdah (The Beginning of the Praises)

- Mawaahibu Naafi’u (The Gifts granted by the Beneficent Lord)

- Jasbul Quloob Ilâ Allâmil Ghuyûb (The Attraction of the Hearts Towards the Lord who Knows all the Hidden)

See also

- Mouride

- Muslim brotherhoods of Senegal

- Touba, Senegal

- Great Mosque of Touba

- Qasida

Further reading

- Reuters report of Touba and the Mourides.

- "Senegal's powerful brotherhoods". BBC News. 2005-09-22. Retrieved 2008-08-09. By Elizabeth Blunt BBC News, 22 September 2005.

- Norimitsu Onishi (2002-05-02). "Industrious Senegal Muslims Run a 'Vatican'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-09., The New York Times, Norimitsu Onishi, 2 May 2002.

- Susan Sachs (2003-07-28). "In Harlem's Fabric, Bright Threads of Senegal". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-09., The New York Times, Susan Sachs, 28 July 2003.

- Sect follows different brand of Islamic law. Reuters, May 22, 2007.

- Timeline of the events of Ahmadou Bamba's life from touba-internet.com.

- Cheikh Anta Babou . Fighting the Greater Jihad: Amadu Bamba and the Founding of the Muridiyya of Senegal, 1853-1913. Ohio University Press (2007) ISBN 978-0-8214-1766-9

- Christian Coulon. The grand Magal in Touba: A religious festival of the Mouride brotherhood of Senegal. African Affairs 98:195-210 (1999).

- John Glover. Sufism and Jihad in Modern Senegal: The Murid Order (Rochester Studies in African History and the Diaspora). University of Rochester Press (2007) ISBN 978-1-58046-268-6

- Mayke Kaag. Mouride Transnational Livelihoods at the Margins of a European Society: The Case of Residence Prealpino, Brescia, Italy. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Volume 34, Issue 2 March 2008, pages 271 - 285.

- Le Mouridisme by Pape N'Diaye, on afrology.com

- David Robinson: French 'Islamic' Policy and Practice in Late Nineteenth-Century Senegal in The Journal of African History, Vol. 29, No. 3 (1988), pp. 415–435.

- Sheik Ahmadu Bamba: Selected Poems. Edited and translated by Sana Camara. Brill Press, 2017. Forthcoming April 2017. ISBN 9789004339187

- Abdou Seye, Des hommes autour du Serviteur de l'Envoyé - Aperçu biographique de disciples de Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, Édition 1438 h / 2017

References

- Ngom, Fallou (2009-01-01). "Aḥmadou Bamba's Pedagogy and the Development of 'Ajamī Literature". African Studies Review. 52 (1): 99–123. doi:10.1353/arw.0.0156. JSTOR 27667424.

- Husain, Ed (2018). The House of Islam. New York: Bloomsbury. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-63286-639-4.

- Mbacke, Saliou (January 2016). The Mouride Order (PDF). World Faiths Development Dialogue. Georgetown University: Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- "Serigne Muhammadu Moustapha Mbacke (1927-1945)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- "Serigne Muhammadu Fadal Mbacke (1945-1968)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- "Serigne Abdul Ahad Mbacke (1968-1989)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- "Serigne Abdu Qadr Mbacke (1988-1989)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- Riccio, Bruno (2004-09-01). "Transnational Mouridism and the Afro‐Muslim Critique of Italy". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 30 (5): 929–944. doi:10.1080/1369183042000245624. ISSN 1369-183X.

- "Hizbut (2006). Contrat de l'exil. Retrieved March 24, 2006". Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- "Touba (2006). Sermon de Cheikh Abdoul Ahad Mbacke. Retrieved March 24, 2006". Touba-internet.com. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- "Hizbut (2006). Serviteur Privilegie. Retrieved March 24, 2006". Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- De Jong, Ferdinand (2016-02-01). "Animating the archive: the trial and testimony of a Sufi saint" (PDF). Social Anthropology. 24 (1): 36–51. doi:10.1111/1469-8676.12286. ISSN 1469-8676.

- Touba (2004). La mission du Cheikh. Retrieved March 15, 2006 , from http://www.touba-internet.com/bmb_martyr.htm#allevents

- Husain, Ed (2018). The House of Islam. New York: Bloomsbury. pp. 151–153. ISBN 9781408872291.

- Tim, Judah (4 August 2011). "Senegal's Mourides: Islam's mystical entrepreneurs". BBC News. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- Abdullah, Z. (2009). "Sufis on Parde: The Performance of Black, African, and Muslim Identities." Journal of American Academy of Religion 77(2): 199-237.

- Abdullah, Zain (2009-06-01). "Sufis on Parade: The Performance of Black, African, and Muslim Identities". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 77 (2): 199–237. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfp016. ISSN 0002-7189. PMID 20681085.

- "Pilgrimage to Touba". BBC.

- toubamica.org

- Roberts, Allen F.; Roberts, Mary Nooter (2008-03-01). "Flickering images, floating signifiers: optical innovation and visual piety in senegal". Material Religion. 4 (1): 4–31. doi:10.2752/175183408X288113. ISSN 1743-2200.

- "Black Studies Center: Information Site". gateway.proquest.com. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Tim, Judah (4 August 2011). "Senegal's Mourides: Islam's mystical entrepreneurs". BBC News. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- "Cafe Touba - Dakar, Senegal | Local Food Guide". Eatyourworld.com. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- Chadwick, Alex (2004-07-02). "Youssou N'Dour, 'Egypt' and Islam". npr.org. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- https://toubamica.org/shaykh-ahmadou-bamba-bibliography/ A short list of Ahmadu Bamba's bibliography]. Murid Islamic Community in America.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ahmadou Bamba. |

- (in French) The wird, its role and purpose by Shaykh Ahmadu Bamba (at-tawhid.net)

- Toubatoulouse.org to download khassaides, audio sounds and pictures

- The Online Murid Library (DaarayKamil.com)

- Passport to Paradise: Sufi Arts of Senegal and Beyond: exhibition and educational program from the Fowler Museum of Cultural History of the University of California at Los Angeles.

- Mouride.com

- daaramouride.asso.ulaval.ca

- Majalis.org

- La Non Violence de Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba

- International Sufi School Khidmatul Khadim

- Article on Shaykh Ahmadou Bamba as Peacemaker

- Official Home Page of the Muridiyya Khidmatul Khadim School

- A modest tribute from Tidjani Négadi (Oran University, Algeria)

- A rare book bridging NY and Touba, Senegal by Peter Bogardus.

- Ways Unto Heaven by Ahmadou Bamba, translation by Abdoul Aziz Mbacke

- Jihad For Peace, about Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, by Abdoul Aziz Mbacke