Alecu Filipescu-Vulpea

Alecu Filipescu-Vulpea, also known as Aleco Filipescul, Alecsandru R. Filipescu[1] or Alexandru Răducanu Filipescu[2] (1775 – November 1856), was a Wallachian administrator and high-ranking boyar, who played an important part in the politics of the late Phanariote era and of the Regulamentul Organic regime. Beginning in the 1810s, he took an anti-Phanariote stand, conspiring alongside the National Party and the Filiki Eteria to institute new constitutional norms. Clashing with the National Party over the distribution of spoils, and only obtaining relatively minor positions in the administration of Bucharest, Filipescu eventually joined a clique of boyars that cooperated closely with the Russian Empire. His conditional support for the Eterists played out during the Wallachian uprising of 1821, when Vulpea manipulated all sides against each other, ensuring safety for the boyars. He returned to prominence under Prince Grigore IV Ghica, but sabotaged the monarch's political reform effort and also seduced his wife Maria. She was probably the mother of his only son, Ioan Alecu Filipescu-Vulpache.

Alecu Filipescu-Vulpea | |

|---|---|

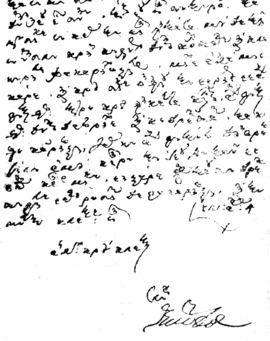

Anton Chladek's portrait of Vulpea, ca. 1830 | |

| Finance Minister of Wallachia | |

| In office March – April 1821 | |

| In office 1828 – ca. 1830 | |

| Justice Minister (Logothete) of Wallachia | |

| In office ca. 1828 – ca. 1833 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1775 Bucharest |

| Died | November 1856 (aged 80 or 81) |

| Nationality | Wallachian |

| Political party | Filiki Eteria (ca. 1816) National Party (ca. 1816–1820) |

| Relations | Ioan Alecu Filipescu-Vulpache (son) Mitică Filipescu (nephew) Gheorghe Bibescu (co-father-in-law) |

| Profession | Civil administrator, philanthropist, innkeeper |

Both Vulpea and Vulpache had important roles in political life under the Russian occupation of 1829–1854. Filipescu Sr worked for the beautification of Bucharest under Pavel Kiselyov, then presided over the departments of Justice and Foreign Affairs. The owner of lucrative estates and an inn in the Bucegi Mountains, he was also a philanthropist, and served for decades on the Wallachian school board alongside his protegé Petrache Poenaru. Although perceived as a committed Russophile, Alecu was a pragmatic conservative who continued seeking alternatives to Russian control, also envisaging a political unification of the Danubian Principalities. He mounted the opposition to Alexandru II Ghica, reluctantly siding with Gheorghe Bibescu and Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei, before running against them in the 1842 election for the Wallachian throne. Bibescu emerged as the winner and then co-opted Vulpea into his circle, making Vulpache his son-in-law. The three of them oversaw the charity established for Princess Zoe, Așezămintele Brâncovenești.

In 1845, Vulpea was created Ban, but was only marginally active before and after the Wallachian Revolution of 1848. Serving Prince Știrbei as adviser on agrarian matters, he died three years before Wallachia's incorporation into the United Principalities, whose administration co-opted his son. His profile endures in political theater from as early as the Phanariote period, and was revived to serve as the antagonist in literary works by Camil Petrescu.

Biography

Eteria and 1821 revolt

Born in Bucharest as the scion of boyar aristocracy, Alecu was the son of Medelnicer Radu (or Răducan) Filipescu, and probably the grandson of Logothete Pană.[3] Their core demesne was the eponymous Filipeștii de Târg, which their ancestors founded ca. 1600,[4] with another ancestral home in Bucharest, on the western side of Podul Mogoșoaiei.[5] In addition to land of this category, Alecu inherited a number of estates in Prahova County, including parcels of the Bucegi Mountains: Jepii, Sorica and Vârful lui Găvan.[6] His mother Maria, from the Văcărescu family,[7] also gave Radu two other sons, Grigore and Nicolae.[8] Early on, Alecu received a thorough education both at home and abroad, and was well-versed in Latin, Ancient and Modern Greek, French and Italian.[9] He was later schooled in the Austrian Empire, with Félix Colson as his tutor and Iancu Văcărescu for a colleague,[10] returning to Wallachia and rising to the post of great Stolnic in 1804. During the 1806 war with Russia, he crossed into Moldavia, and later into Russia.[11]

By 1816, he was in contact with Greek immigrant circles, and reportedly joined the secret society known as Filiki Eteria, which wanted to have the Balkans, Wallachia included, removed from the Ottoman Empire.[12] Nevertheless, Filipescu remained a Romanian nationalist opposed to Wallachia's Hellenization, and also frequented the National Party of Dionisie Lupu, Metropolitan of Wallachia.[13] He and his entire family opposed Prince John Caradja, a Phanariote, who took special measures to have them silenced.[14] Apparently, Filipescu was also personal friends with another Caradja adversary, the innkeeper Manuc Bei, with whom he engaged in land speculation.[15] In 1818, he also set up his own business as a restaurateur, founding his own inn-and-salon near Sorica.[16]

In 1820, under Prince Alexandros Soutzos, Filipescu detached himself from the National Party, joining the Russophiles. He was widely seen as a liaison for the Russian consul, Alexander Pini, who mediated between the Wallachian boyardom and the Eteria conspirators.[17] Within the Boyars' Divan, Alecu and Iordache Filipescu now opposed the National Party, whose chiefs were Grigore Brâncoveanu and Barbu Văcărescu. The latter group managed to win Soutzos' favors and took the top boyar offices, with Filipescu settling for the title of Vornic.[18] This job saw him taking over the administration of Bucharest, effectively as City Mayor.[19] With Iordache Golescu, he audited the city finances, discovering that Bucharest was unable to pay for new bridges.[20] His distant relative and political friend Iordache Filipescu held him in high regard, and viewed him as a trusted confidant.[11]

According to some reports, Vulpea was one of the three Caimacami (regents) upon Soutzos' death.[21] His brother Grigore, also credited as a Caimacam, was himself involved in the Russian conspiracy during those months. He was unreliable from Pini's perspective, and looked to Austria for additional guidance.[22] As the Eterists and the National Party colluded in the build-up to the Greek Revolution, the Filipescus withdrew from the intrigues. In June 1820, by his own admission, Dimitrie Macedonski wanted to co-opt Alecu into a rebellion against Soutzos and the Phanariotes. Filipescu agreed on principle that "it would be possible and rather good that we remove this country of ours from the yoke of [Phanariote] tyrants";[23] still, he adamantly refused to be involved beyond this statement, feeling himself betrayed by the National Party.[24] However, with Pini's assurances and possibly seeking appointment in a revolutionary government, he abetted the Eterists, without formally rejoining their movement.[25]

Vladimirescu's rebellion

Ultimately, in 1821, a Wallachian anti-Phanariote rebellion erupted in conjunction with an Eterist invasion by the Sacred Band. Filipescu may have played a role in its instigation, being described by author Constantin V. Obedeanu as a "protector and ally" of the rebel leader, Tudor Vladimirescu.[26] At Ciorogârla, Dinicu Golescu presented Vladimirescu with a letter of support from 77 nationalist boyars—including himself and Filipescu. The document, rendered compromising upon Vladimirescu's radicalization and defeat, was probably absconded and destroyed.[27] As he advanced on Bucharest in February 1821, Vladimirescu took a stand against those boyars he viewed as accomplices of the Phanariotes, and publicly announced that he wanted Iordache Filipescu and others beheaded.[28] Alecu and Iordache Filipescu, alongside Metropolitan Dionisie, expressed their alarm in a letter to Pini, asking for protection and guidance—they believed that the rebels were controlled by Russia, until Pini denied that this was the case.[29] With most notabilities, including his two brothers,[30] fleeing into the Principality of Transylvania, Alecu Filipescu stayed behind in Bucharest, alongside Bishop Ilarion Gheorghiadis, Nae Golescu, and Mihalache Manu.[31]

Taking control of the treasury by March 14, Filipescu began supplying the Eterist troops already present in Bucharest with salaries, lodgings, and horse fodder.[32] The first two meetings between the rebel and the Vornic, at Cotroceni, were tense: on March 20, Vladimirescu informed him that he could not discern any Russian support for Wallachia's government, and asked that the boyars surrender Bucharest. This they did the following day.[33] According to oral history, when Filipescu voiced his fear, Vladimirescu's secretary, Nicolae Popescu, informed him that if the rebels had wanted him dead, he would already have been "slashed".[34] Subsequently, Filipescu became a representative of his boyar class to Vladimirescu's headquarters. He performed his mission so well that the nickname Vulpea ("the fox") was bestowed.[35] In March, Filipescu, Metropolitan Dionisie, and Gheorghiadis signed their names to a pledge of allegiance, effectively recognizing Vladimirescu as head of state, while preserving an administrative role for the Boyars' Divan.[36] Filipescu won Vladimirescu's confidence, and relayed his demands to the Divan;[37] his own secretary, Pitar Teodorache, became Vladimirescu's scribe, while Gheorghiadis translated his manifestos into French.[26]

Within a few weeks, the Eterist–Wallachian insurgencies elicited a military response from the Ottoman Army. Faced with this peril, and possibly influenced by Vulpea (who feared that antagonizing the Ottomans would destroy all remaining Wallachian autonomy),[38] Vladimirescu sought to relieve himself of his alliance to the Eteria. In letters he exchanged with Filipescu in the early days of April, he declared his loyalty to the Ottomans, and insisted that he could persuade them to topple the Phanariotes.[39] On April 4, he allowed Vulpea and Gheorghiadis to send letters of submission to the Sublime Porte, but would not openly associate himself with them.[40]

By April 10, soon after Vladimirescu had met with the Ottoman envoys, Filipescu was informed that Ottoman forces held Roșiorii de Vede.[41] Alongside the Metropolitan, Vulpea then asked that the Divan be granted safe passage to Transylvania. Vladimirescu allowed them to exit Bucharest under armed guard, but only to detain them at Golescu's Belvedere Manor, outside Ciurel. Here, they were besieged by warlord Binbaşı Sava Fochianos, who led a crew of Arnauts and militarized tanners; eventually, the boyars persuaded Fochianos to withdraw.[42] Historian Emil Vârtosu believes that Filipescu and the others were arrested when Vladimirescu realized that they would not support his egalitarian agenda, and that they still believed themselves unbound by his rules.[43] However, in the notebooks kept by Ivan Liprandi, Filipescu and Gheorghiadis appear as a double-dealers who influenced Vladimirescu and the "intellectually frail" Metropolitan to take decisions that favored the Divan. Thanks to their intercession, the boyars could escape to safety before the violent fallout between Vladimirescu and Fochianos, which resulted in the scattering of Wallachian forces.[44]

By October 1822, Filipescu, Gheorghiadis and Dionisie had rejoined the other boyar refugees at Kronstadt. They were guests of Kaiser Francis I, who allowed them to have their own private police.[45] Financially insecure, they asked for loans from the Transylvanian Saxons, and eventually appealed to Grigore IV Ghica, the new Prince of Wallachia, to sponsor their return to Bucharest.[46] During this post-Phanariote reign, alongside the prince's brothers (Mihalache, Alexandru and Costache), Vulpea joined a literary society for the promotion of Romanian culture—founded and led by Dinicu Golescu.[47] In late 1826, following the Akkerman Convention, through which Russia imposed reforms of Wallachia, Prince Ghica selected Vulpea, Ioan Câmpineanu, Alexandru Vilara, and other members of Golescu's society, to serve on his personal committee for modernization.[48] In 1827, he also appointed Vulpea Great Logothete of the Upper Country,[11] which was roughly the Ministry of Religious Affairs.[21]

Regulamentul adoption

The reform initiative had unintended consequences, with the committee ignoring its stated objectives and openly criticizing Ghica's policy in distributing pensions. However, the very existence of such a body irritated Sultan Mahmud II, who viewed the boyars as pawns of Russian influence.[49] Vulpea also encountered hostility from the Ghica family: he had seduced the prince's wife, Maria Hangerli-Ghica, who was reportedly the mother of his son, Ioan Alecu, or simply Alecu.[50] According to other sources, his mother was actually Tarsița Filipescu, a distant relative of Alecu's.[51] Also known as Vulpache ("little fox"), Ioan was born in Bucharest on May 12, 1809,[52] although some early records have 1811[53] or 1800.[54] To contemporaries, Vulpache was known as Alecu's adoptive son.[55]

The reform committee was largely stagnant by 1828,[56] with Vulpea also focused on his other princely assignments—he was the posthumous custodian of Dositei's estate, with Neofit Geanoglu at his side.[57] Months later, Wallachia and Moldavia fell to a Russian military occupation. Filipescu took over as Finance Minister and Vornic in the new cabinet imposed by the Russians, replacing Mihalache Ghica.[58] The new Russian supervisor, Pavel Kiselyov, also appointed him to a Russo–Wallachian commission which oversaw the paving of Bucharest streets in cobblestone.[59] He was additionally a member of the beautification and sanitation committee, with Constantin Cantacuzino and Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei.[60] In addition to his old home, he now owned a villa in the area currently known as Dorobanți;[61] and a townhouse east of Podul Mogoșoaiei, near Popa-Cozma Church, where he was neighbors with Barbu Văcărescu and Barbu Catargiu.[62]

While Kiselyov was in the country in the late 1820s and early 1830s, Filipescu was Minister of Justice (Logothete). Under Kiselyov's watch, he helped draft Regulamentul Organic, the Wallachian constitution.[63] He was also one of three caretakers (efori) of the national school board, alongside Știrbei and Ștefan Bălăceanu. Their program of education was directly inspired from a letter drafted in 1831 by Kiselyov, and called for the designation of at least one public school in each locality.[64] In June 1828, Filipescu obtained a state scholarship for the aspiring engineer Petrache Poenaru to study at the Paris Conservatory of Arts and Crafts, later appointing him to teach at Saint Sava.[65] He later donated stone quarried on his Bucegi property for writing slates, to be used in rural schools across Wallachia.[66] From May 1832, Vulpea involved himself in settling disputes over the ownership and trading of Roma slaves.[67] He also helped to capture and sentence the bandit Gheorghe sin Medrea in June 1833—possibly the last case of birching to be recorded in Wallachia.[68] Together with other administrators, in 1836 he gave the order to recolonize Severin, which soon replaced Cerneți as the capital of Mehedinți County.[69]

Vulpea later transferred to the Foreign Ministry. He had become especially powerful, but owed his influence to his "absolute adherence to the Russian political line in Wallachia."[70] During the 1830s, he befriended Kiselyov's aide, Karneev, who was passionate about coin collecting. Vulpea fed this hobby by providing the Russian with coins dug up at Caracal and elsewhere, which Karneev transported to his museum in Saint Petersburg.[71] Meanwhile, however, Vulpea continued his marginal contribution to the nationalist project when, as Logothete, he donated "a years' worth" of estates' socage to Câmpineanu's Philharmonic Society,[72] and allegedly wanted to have Wallachia ruled by a foreign prince, as a guarantee against Russian and Ottoman interference.[73] He also continued to have fights with the other boyars, especially so in 1835, when he asked treasurers Câmpineanu and Iancu Filipescu-Buzatu for a refund of his alleged expenses and damages incurred in 1821, which he claimed ran at 287,000 thaler.[74]

Grigore Filipescu wanted the throne for himself, but was ignored by the Russians and had to settle for the position of chief justice.[11] Vulpache, meanwhile, was a student in Paris, where he immersed himself in liberal-nationalist politics, alongside colleagues Ion Ghica and Nicolae Crețulescu.[75] He also began his administrative career during the early Regulamentul years: in 1835 or 1842, he served as Ilfov County judge.[76] He was a protege of Kiselyov's, who obtained for him the office of Aga (or prefect) of the Bucharest police.[77] From 1838, he was also Bucharest's Mayor, with the title of Vornic, and from 1842 led the Commune Council.[77]

1840s intrigues

Although favored by Kiselyov, Alecu Filipescu was detested by the Russian-appointed prince, Alexandru II Ghica, who was Grigore Ghica's son and possibly Vulpache's half-brother. According to his younger friend, Grigore Lăcusteanu, Vulpea only protected himself from Ghica by embracing the Russophile agenda: "[Ghica] would have otherwise beheaded me".[78] As early as October 1838, he instigated a complaint against Ghica, which the boyars sent to Nicholas I of Russia. The liberal boyar Alexandru G. Golescu contended that theirs was an absurd position: "I could not understand how these people with some common sense, all of whom detest the Russian government, but at the same time caress it, could produce such an imprudent and base action".[79] According to the same Golescu, Vulpea circulated rumors that Ghica was under a formal Russian investigation. The claim was baseless, but Vulpea hoped "to take revenge on the prince" by tarnishing his reputation.[80]

This was also the period when Mitică Filipescu, his brother Grigorie's only son,[81] was arrested for conspiring against the throne. According to Lăcusteanu, the incident was part of a Russophile and Filipescu-family intrigue, rather than a liberal or nationalist revolt.[82] Similarly, the Andronescu brothers, clients of Grigore Filipescu, recorded a rumor that "all the Filipescu clan was in on that conspiracy."[83] An ex officio member of the reconstructed Divan (or Ordinary Assembly), Vulpea helped maneuver the opposition against Ghica, alongside Vilara and the young jurist Gheorghe Bibescu: immediately after the legislative election of 1841, they drafted a special report, presented to Ghica by the entire Assembly.[84] It depicted Ghica as an anti-patriot and a foreigner, emphasizing his Albanian origins.[85] Ghica was eventually disgraced by Sultan Abdulmejid I and deposed in October 1842. Alongside Câmpineanu, Vilara, and Ion Ghica, Vulpea suggested the appointment of Mihail Sturdza, the reigning Prince of Moldavia, for the throne in Bucharest. Their proposed personal union was quickly vetoed by Russia.[86]

Subsequently, Vulpea became one of 21 candidates in the princely election of December 1842, seen by contemporaries as the "boyar party" (or anti-National Party) favorite.[87] Mistrusted as a Muscal, aging, and visibly suffering from hernia, he was credited with few chances, and was aware of it; however, he reportedly informed Lăcusteanu that he was only in the race to prevent either of the "Oltenian" brothers, Bibescu and Știrbei, from winning the throne.[88] Vulpea came second in the first pool of candidates, losing to Iordache Filipescu 63 to 84.[89] Bibescu emerged as the winner, but soon found that his legislative project were being blocked by a coalition of Ghicas and Filipescu. He responded by isolating the former and coaxing the latter into cooperation.[90] By 1844, Bibescu had made Alecu his great Ban.[91]

In June 1843, Vulpea was elected President of the Most-High Divan, the supreme court of justice, with Vilara as the Justice Minister.[92] He also continued his work at the national school board, which was now supervised by Constantin Cantacuzino (later replaced with Mihai Ghica), and also included Poenaru.[93] In October 1843, he sided with Bibescu, supporting the controversial Russian prospector Alexander Trandafiloff, and allowed him to work on his own estates.[94] These had increased in number since 1834, when he had bid on Cazacu Mountain, outside Brebu.[95] In 1844, Vulpea also purchased land outside Bușteni, Clăbucetul Taurului, Duțca and Râșnoava, previously owned by the Sachelarie boyars; the same year, however, he also donated Clăbucetul to Predeal Monastery.[96]

Also in 1844, the Assembly appointed him, together with Vilara and Emanoil Băleanu, to oversee Așezămintele Brâncovenești. This was a charity set up for Bibescu's estranged wife Zoe Brâncoveanu, whom the prince had declared insane.[97] His support for the Prince was countered by the other senior Filipescus. Their vocal opposition contributed to Bibescu's suspension of the Assembly for two years.[98] Power then shifted toward the princely camarilla. As noted by Poenaru, Vulpea's own accumulation of offices was harming Wallachian education: the Assembly's judgments caused resentment among the lesser boyars, who took revenge by sabotaging efforts to create new schools.[99] Bibescu also became Alecu's in-law in January 1845, when Vulpache, who simultaneously served as Finance Minister and Bucharest Council chairman,[100] married Bibescu's daughter Eliza.[101] The marriage was loveless: Eliza, who had been romantically involved with the British diplomat Robert Gilmour Colquhoun, registered her objection.[55] Later that year, at Brăila, Vulpea handled the reception of Bibescu's new bride, Marițica Văcărescu-Ghica.[55]

Later career and death

After 1846, the regime tried to reconcile with young liberals, and Vulpache emerged as a mediator between the two sides.[102] Nevertheless, tensions between the conservatives and the liberals brought down the regime: a Wallachian Revolution erupted in mid 1848, and Bibescu was forced to abdicate and leave into exile. Vulpache also fled the country,[103] returning after pacification with the Imperial Russian Army, which controlled part of Bucharest, and serving for a while as Minister of the Interior.[104] His father stayed behind in Bucharest. As the revolutionary government fell and Cantacuzino, as Caimacam, inaugurated a conservative regime, he was reappointed to the school board alongside Poenaru, Băleanu, and, from 1851, Apostol Arsache and Ion Emanuel Florescu.[105] While there, he ordered budget cuts, sacking teachers who had participated in the Revolution and were unrepentant. His son, as Secretary of State, carried out the order,[106] and, as records of the time suggest, the number of active schools dropped rapidly.[107] Meanwhile, Vulpea was also given a position on a committee which evaluated the agrarian issue. Composed of conservatives, it outlined the standard alternative to land reform, suggesting a gradual termination of socage and corvée through boyar–peasant contracts.[108]

The new prince, Știrbei, appointed Vulpache Finance Minister,[109] then Foreign Minister, and eventually Minister of Justice.[103] In 1852, he was also chief justice.[110] Father and son, alongside Ioan Manu and Mihalache Cornescu, served together as caretakers of Așezămintele Brâncovenești. In this capacity, they fought for continued ownership of Brâncoveanu's slaves.[111] During the interregnum sparked by the Crimean War, Vulpache served on the Administrative Council, alongside Constantin and Ion C. Cantacuzino, as well as Constantin Năsturel-Herescu.[112] When Știrbei was replaced with Alexandru Ghica, who returned as Caimacam, Filipescu Jr served as President of the Bucharest Assembly Commission from 1856,[103] also taking over for his father on the school board.[113] Vulpea died the same year,[103] a date not shown in full on his grave at Mavrogheni Church, Bucharest—which simply has "November".[54]

Ahead of the January 1859 election, Vulpache himself became one of the three Caimacami. In this capacity, he channeled support for both Bibescu and Știrbei,[114] or, according to one account, was a candidate in his own right.[115] A prominent conservative, he returned as Prime Minister and Justice Minister of Wallachia after its integration into the United Principalities.[116] Retiring as a councilor for the Court of Cassation,[7] he died in August 1863, and was buried at Mavrogheni Church, next to his father.[54] His son Alexandru died without heirs,[61] but the Filipescu line was notably maintained through Nicolae Filipescu. Married to Safta Hrisoscoleu, he was the paternal grandfather of Conservative Party politico Nicolae G. Filipescu, and the maternal grandparent of Ion G. Duca, leader of the National Liberal Party.[117]

The Dorobanți villa, rebuilt by Alexandru Filipescu in 1913, was left to Constantin Basarab Brâncoveanu, and went on to serve as the head offices of the National Liberal Party. The street is known as Modrogan,[61] which was also Vulpea's alternative nickname.[118] Vulpea's life and deeds had already made a mark on literature and the theater, beginning in 1818 with the comedy Generalul Ghica, possibly written by Costache Faca. It shows Vulpea as a sex symbol, with Sultana Ghica swooning over his portrait.[119] Vulpea was also an unseen character in an unpublished play by his former colleague Iordache Golescu, which romanticizes his encounter with Vladimirescu.[120] Ion Ghica also relayed fictionalized anecdotes about Vulpea as the protector of barbers and the object of adulation by the clinically insane.[121]

Much later, in 1921, Nicolae Iorga also made Vulpea a character in his five-act drama, Tudor Vladimirescu.[122] In the 1950s, Camil Petrescu wrote him into the socialist-realist play Nicolae Bălcescu, as an antagonist. Marcel Anghelescu appeared as Vulpea in the early stagings, showing him as a man of "somnolent cruelty", "decrepit, bloated, and haughty".[123] The Ban is also present in Petrescu's novel Un om între oameni as one of the "nefarious" Russophile characters, even though the Russians themselves are depicted as savior-like figures.[124]

Notes

- Achim et al., pp. 63–64, 138, 158

- Preda, p. 54

- Iorga (1902), pp. XXX–XXXI

- Brătescu et al., p. 201

- Papazoglu, p. 67

- Brătescu et al., pp. 108, 246, 249–250, 315, 459–460, 485, 534–535, 633

- Fotino, p. 123

- Iorga (1902), pp. XXX–XXXI, XXXVI–XXXVII

- Rosetti, p. 74

- Ghica & Roman, p. 342

- Iorga (1902), p. XXXVII

- Vianu & Iancovici, p. 74

- Xenopol, p. 49

- Andronescu et al., p. 46; Camariano & Capodistria, pp. 101, 104; Ghica & Roman, p. 147; Golescu & Moraru, pp. 29–30, 70, 429; Ploscaru, p. 94

- Camariano & Capodistria, p. 101

- Brătescu et al., p. 108

- Ploscaru, pp. 91–94, 98

- Ploscaru, pp. 92–93

- Potra (1990, I), p. 505

- Golescu & Moraru, pp. 67, 433

- Papazoglu, p. 90

- Iorga (1902), pp. XXXVI–XXXVII. See also Vârtosu (1932), p. 4

- Vianu & Iancovici, p. 75

- Ploscaru, p. 94

- Ploscaru, p. 98

- Obedeanu, p. 26

- Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 78, 81

- Vianu & Iancovici, p. 80. See also Hêrjeu, p. 38

- Filitti, pp. 46, 54; Obedeanu, pp. 29–31; Vârtosu (1932), pp. 140–141

- Filitti, pp. 64–65; Iorga (1902), p. XXXVII; Obedeanu, p. 29–31; Xenopol, pp. 124–125

- Golescu & Moraru, pp. 54–55, 433; Iorga, Izvoarele contemporane..., pp. 57–58, 257, 284

- Vârtosu (1932), pp. 65–66

- Obedeanu, p. 31. See also Filitti, p. 54

- Octavian Ungureanu, "Tudor Vladimirescu în conștiința argeșenilor. Momente și semnificații", in Argessis. Studii și Comunicări, Seria Istorie, Vol. VIII, 1999, p. 171

- Bodin, p. 28; Golescu & Moraru, pp. 54–55; Rosetti, p. 74

- Filitti, pp. 54–55; Obedeanu, pp. 31–32; Tascovici, pp. 180–181

- Filitti, p. 55; Tascovici, p. 177

- Filitti, pp. 2, 46, 51–54, 66

- Filitti, p. 66

- Bodin, p. 21

- Obedeanu, pp. 33–34

- Iorga, Izvoarele contemporane..., pp. 67–68, 284–285

- Vârtosu (1932), pp. XIV–XV

- Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 81–82

- Papazoglu, p. 87

- Vârtosu (1932), pp. 167–172

- Hêrjeu, p. 68; Xenopol, pp. 134, 147–148

- Filitti, pp. 140–142, 146; Xenopol, pp. 134, 147–148

- Xenopol, pp. 147–148

- Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 229. See also Filitti, p. 137; Iorga (1902), p. XXXVII

- Andronescu et al., p. 105

- Angelescu, p. 32

- Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 279; Rosetti, p. 74

- Nicolae Iorga, Inscripțiĭ din bisericile Romănieĭ, p. 283. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1905. OCLC 606281810

- Iorga (1938), p. 77

- Filitti, p. 140; Xenopol, p. 148

- "Apel la Romania, pentru ospitalitatea que se dă de dênsa avereĭ rĕposatutui Dositie Filitis (Mitropolit)", in Romanulu, January 8, 1864, (annex) pp. 1–2

- Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, pp. 42–43, 229

- Potra (1990, I), p. 230

- Potra (1990, I), pp. 292, 371; (1990, II), p. 196

- (in Romanian) Alexandru Popescu, "Casele Bucureștilor (IX). Palate și case boierești, nobiliare", in Ziarul Financiar, October 1, 2015

- Dan Berindei, "Înființarea Societății Academice și localurile Academiei", in Buletinul Monumente și Muzee, Vol. I, Issue 1, 1958, pp. 242–243

- Iorga (1902), p. XXXVII; Rosetti, p. 74

- Urechia, p. 34

- Potra (1963), pp. 43, 85, 302, 323

- Urechia, pp. 6, 52

- Achim et al., pp. 10–11, 63–64

- Potra (1990, II), pp. 187, 332

- V. Demetrescu, Istoria orașului Severin, pp. 97–99. Severin: Tipografia Emil J. Knoll, 1883. OCLC 895229423

- Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 229

- Emil Vârtosu, "Glosa numismatică", in Buletinul Societății Numismatice Române, Nr. 57–58/1926, pp. 21, 23

- Potra (1990, I), p. 527

- Hêrjeu, p. 94; Xenopol, p. 175

- Bodin, p. 36

- Ghica & Roman, pp. 14, 197

- Angelescu, p. 34; Rosetti, p. 75

- Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 279

- Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 137

- Bodea, p. 212

- Bodea, p. 213

- Angelescu, p. 32; Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, pp. 123, 254

- Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, pp. 123–124

- Andronescu et al., p. 83

- Andronescu et al., pp. 88–89; Anghel Demetriescu, "Barbu Katargiu", in Barbu Catargiu, Discursuri parlamentare. 1859–1862 iunie 8, p. 20. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1914. OCLC 8154101

- Preda, pp. 58–59

- Hêrjeu, pp. 97–98; Xenopol, p. 181. See also Ghica & Roman, pp. 215–216

- Hêrjeu, p. 99

- Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, pp. 137–138

- Andronescu et al., pp. 93–94; Preda, p. 54

- Iorga (1938), pp. 71, 73

- Iorga (1938), p. 71; Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 229; Rosetti, p. 74

- Andronescu et al., pp. 99–100

- Potra (1963), pp. 138–139, 143, 203, 310, 349–352

- Andronescu et al., p. 102

- Brătescu et al., p. 92

- Brătescu et al., pp. 128–129, 159, 189, 460, 485

- Andronescu et al., pp. 104–105

- Iorga (1938), pp. 75–76, 79–80

- Potra (1963), p. 143

- Potra (1990, I), p. 299; II, p. 42

- "Tages Nachrichten", in Mitauische Zeitung, Nr. 2/1845, p. 8

- Iorga (1938), p. 142

- Rosetti, p. 75

- Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, pp. 188, 191

- Potra (1963), pp. 166–167, 170; Urechia, pp. 79, 84, 85

- Urechia, pp. 79, 82

- Nicolae Gh. Teodorescu, "Muzeul din Mușătești, județul Argeș, mărturie a contribuției satului la istoria patriei", in Muzeul Național (Sesiunea Științifică de Comunicări, 17–18 Decembrie 1973), Vol. II, 1975, p. 110

- Angela-Ramona Dumitru, "Principele Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei (1849–1856). Precursor al conservatorismului românesc", in Revista de Științe Politice, Nr. 13/2007, p. 68

- Achim et al., p. 151

- Angelescu, p. 34

- Achim et al., pp. 137–138, 158

- Nicolae Ciachir, "Unele aspecte privind orașul București în timpul războiului Crimeii (1853—1856)", in București. Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie, Vol. III, 1965, p. 200

- Potra (1963), p. 175

- Hêrjeu, pp. 197–199; Xenopol, p. 377

- Iorga (1938), pp. 339–340

- Angelescu, p. 34; Xenopol, pp. 389, 394

- Fotino, pp. 44, 279, 297

- Papazoglu, p. 169

- Eugen Simion, "Tot despre modelul grec în cultura română: parabole mitologice, comedii de moravuri. Belphegor în lumea balcanicã (II)", in Caiete Critice, Nr. 2/2011, p. 5

- Golescu & Moraru, pp. 54–55

- Ghica & Roman, pp. 91–92, 96–97, 355

- Nicolae Iorga, Tudor Vladimirescu. Dramă în cinci acte. Craiova: Ramuri, [1921]

- Florin Tornea, "Drumul spre Hlebnikov", in Revista Teatrul, Nr. 1/1956, p. 28

- (in Romanian) Alex. Ștefănescu, "Camil Petrescu – scrierile postbelice", in România Literară, Nr. 13/2004

References

- Venera Achim, Raluca Tomi, Florina Manuela Constantin (eds.), Documente de arhivă privind robia țiganilor. Epoca dezrobirii. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 2010. ISBN 978-973-27-2014-1

- Șerban Andronescu, Grigore Andronescu (contributor: Ilie Corfus), Insemnările Androneștilor. Bucharest: National History Institute, 1947. OCLC 895304176

- Constantin Angelescu, "Contribuții la istoria învățământului. Studenți români la Paris în 1820—1840", in Revista Generală a Învățământului, Nr. 1–2/1932, pp. 31–35.

- Cornelia Bodea, Lupta românilor pentru unitatea națională, 1834–1849. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 1967. OCLC 1252020

- D. Bodin, "Premize la un curs despre Tudor Vladimirescu", in Revista Istorică Română, Vol. XIV, Part I, 1944, pp. 15–39.

- Paulina Brătescu, Ion Moruzi, C. Alessandrescu (eds.), Dicționar geografic al județului Prahova. Târgoviște: Tipografia și Legătoria de Cărți Viitorul, Elie Angelescu, 1897. OCLC 55568758

- Nestor Camariano, Jean Capodistria, "Trois lettres de Jean Capodistria, ministre des affaires étrangères de Russie, envers Manouk Bey (1816–1817)", in Balkan Studies, Vol. 11, 1970, pp. 97–105.

- Ioan C. Filitti, Frământările politice și sociale în Principatele Române de la 1821 la 1828 (Așezământul Cultural Ion C. Brătianu XIX). Bucharest: Cartea Românească, 1932. OCLC 876309155

- George Fotino, Din vremea renașterii naționale a țǎrii românești: Boierii Golești. II: 1834–1849. Bucharest: Monitorul Oficial, 1939.

- Ion Ghica (contributor: Ion Roman), Opere, I. Bucharest: Editura pentru literatură, 1967. OCLC 830735698

- Iordache Golescu (contributor: Mihai Moraru), Scrieri alese. Teatru, Pamflete, Proză, Versuri, Proverbe, Traduceri, Excerpte din Condica limbii rumânești și din Băgări de seamă asupra canoanelor grămăticești. Bucharest: Cartea Românească, 1990. ISBN 973-23-0114-7

- N. N. Hêrjeu, Istoria Partidului Național Liberal; De la origină până în zilele noastre. Volumul 1. Bucharest: Institutul de Arte Grafice Speranța, 1915. OCLC 38789356

- Nicolae Iorga,

- "Prefață", in Constantin Căpitanul Filipescu, Istoriile domnilor Țării-Românești cuprinzînd istoria munteană de la început până la 1688, pp. I–XXXVIII. Bucharest: I. V. Socecu, 1902. OCLC 38610972

- Izvoarele contemporane asupra mișcării lui Tudor Vladimirescu. Bucharest: Librăriile Cartea Românească & Pavel Suru, 1921. OCLC 28843327

- Istoria românilor. Volumul 9: Unificatorii. Bucharest & Vălenii de Munte: Așezământul Grafic Datina Românească, 1938. OCLC 490479129

- Grigore Lăcusteanu (contributor: Radu Crutzescu), Amintirile colonelului Lăcusteanu. Text integral, editat după manuscris. Iași: Polirom, 2015. ISBN 978-973-46-4083-6

- Constantin V. Obedeanu, Tudor Vladimirescu în istoria contimporană a României. Craiova: Scrisul Românesc, 1929. OCLC 895213203

- Dimitrie Papazoglu, Istoria fondării orașului București. Istoria începutului orașului București. Călăuza sau conducătorul Bucureștiului. Bucharest: Fundația Culturală Gheorghe Marin Speteanu, 2000. ISBN 973-97633-5-9

- Cristian Ploscaru, "Tradiție și inovație în demersul politic al lui Tudor Vladimirescu (I)", in Analele Universității din Craiova. Seria Istorie, Vol. XV, Issue 1, 2010, pp. 87–100.

- George Potra,

- Petrache Poenaru, ctitor al învățământului în țara noastră. 1799–1875. Bucharest: Editura științifică, 1963.

- Din Bucureștii de ieri, Vols. I–II. Bucharest: Editura științifică și enciclopedică, 1990. ISBN 973-29-0018-0

- Cristian Preda, Rumânii fericiți. Vot și putere de la 1831 până în prezent. Iași: Polirom, 2011. ISBN 978-973-46-2201-6

- Dimitrie R. Rosetti, Dicționarul contimporanilor. Bucharest: Editura Lito-Tipografiei Populara, 1897.

- Radu Tascovici, "Participarea Episcopului Ilarion Gheorghiadis al Argeșului la Revoluția lui Tudor Vladimirescu", in Mitropolia Olteniei, Nr. 1–4/2012, pp. 171–183.

- V. A. Urechia, Scólele satesci în Romănia. Istoricul lor de la 1830—1867. Cu anesarea tuturorŭ documentelorŭ relative la cestiune. Bucharest: Tipografia Naționale, Întreprind̦etor C. N. Rădulescu, 1868. OCLC 465916431

- Emil Vârtosu, 1821: Date și fapte noi. Bucharest: Cartea Românească, 1932. OCLC 895101736

- Al. Vianu, S. Iancovici, "O lucrare inedită despre mișcarea revoluționară de la 1821 din țările romîne", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Nr. 1/1958, pp. 67–91.

- A. D. Xenopol, Istoria partidelor politice în România. Bucharest: Albert Baer, 1910.