Battle of Alarcos

Battle of Alarcos (July 18, 1195),[2] was a battle between the Almohads led by Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur and King Alfonso VIII of Castile.[3] It resulted in the defeat of the Castilian forces and their subsequent retreat to Toledo, whereas the Almohads reconquered Trujillo, Montánchez, and Talavera.[2]

| Battle of Alarcos | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Reconquista | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Alfonso VIII of Castile Diego López de Haro |

Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur Pedro Fernández de Castro | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Order of Évora Order of Santiago |

Marinid volunteers Zenata Archers Hintata Andalusian Forces | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~30,000 (Al-Himyari) | unknown | ||||||

Background

In 1189 the Almohad caliph Yaqub al-Mansur returned from Marrakesh to fight the Portuguese who, with the help of a Christian alliance, had taken over Silves. He successfully recaptured the city and went back to his capital.

An armistice between the Almohads and the Christian kings of Castile and León ensued. At the expiration of the truce, and having received news that Yaqub was gravely ill in Marrakesh and that his brother Abu Yahya, the governor of Al-Andalus, had crossed the Mediterranean to declare himself king and take over Marrakesh, Alfonso VIII of Castile decided to attack the region of Seville in 1194.[4] A strong host under the archbishop of Toledo (Martín López de Pisuerga), which included the military Order of Calatrava, ransacked the province. Having successfully crushed his brother's ambitions, Yaqub al-Mansur was left with no choice other than to lead an expedition against the Christians, who were now threatening the northern province of his empire.[4]

On the first day of June, 1195, he landed at Tarifa. Passing through the province of Seville, the main Almohad army reached Cordova on June 30, reinforced by the few troops raised by the local governors and by a Christian cavalry contingent under Pedro Fernández de Castro, who held a personal feud against the Castilian king. On July 4 Ya'qub moved out of Cordova; his army crossed the pass of Muradal (Despeñaperros) and advanced through the plain of Salvatierra. A cavalry detachment of the Order of Calatrava, plus some knights from nearby castles, tried to gather news about the Almohad strength and its heading; they were surrounded by Muslim scouts and almost exterminated, but managed to supply information to the Castilian king.

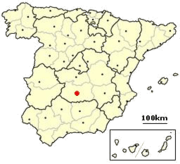

Alfonso gathered his forces at Toledo and marched down to Alarcos (al-Arak, in Arabic), near the Guadiana River, a place which marked the Southern limit of his kingdom and where a fortress was under construction. He intended on barring the access to the rich Tagus valley, and did not wait for the reinforcements the Kings Alfonso IX of León and Sancho VII of Navarre were sending.[3] When on July 16 the Almohad host came in view, Yaqub al-Mansur did not accept battle on this day or the day after, preferring to give rest to his forces; but early the day after that, Wednesday, July 18, the Almohad army formed for battle around a small hill called La Cabeza, two bow-shots from Alarcos.

Battle

Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur gave to his vizier, Abu Yahya ibn Abi Hafs, command of a very strong vanguard: on the first line the Bani Marin volunteers under Abu Jalil Mahyu ibn Abi Bakr, with a big body of archers and the Zenata Tribe; behind them, on the hill itself, the vizier with the Amir's banner and his personal guard, from the Hintata tribe; to the left the Arab host under Yarmun ibn Riyah; and to the right, the al-Andalus forces under the popular Caid Ibn Sanadid. Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur himself held command of the rearguard, which comprised the best Almohad forces commanded by Yabir ibn Yusuf, Abd al-Qawi, Tayliyun, Muhammad ibn Munqafad, and Abu Jazir Yajluf al-Awrabi and the black guard (of black Africans). It was a formidable army, whose strength Alfonso had badly underestimated. The Castilian king put most of his heavy cavalry in a compact body, about 8,000 strong, and gave its command to Diego López de Haro, lord of Vizcaya. The king himself would follow with the infantry and the Military Orders.

The Christian cavalry charge was somewhat disordered. The knights crashed against the Zanatas and Bani Marin and dispersed them; lured by the Amir's standard, they charged uphill: Vizier Abu Yahya was killed,[5] and the Hintata fell almost to a man trying to protect themselves. Most of the knights turned to their left and after a fierce struggle they routed the al-Andalus forces of Ibn Sanadid. Three hours had passed; just afternoon, in the intense heat, the fatigue and the missiles which kept falling on them took their toll of armoured knights. The Arab right under Yarmun had been enveloping the Castilian flank and rear; at this point the best of the Almohad forces attacked, with the sultan himself clearly visible in the front ranks; and finally the knights were almost completely surrounded.

Alfonso advanced with all his remaining forces into the melee, only to find himself assaulted from all sides and under a rain of arrows. For some time he fought hand-to-hand, until removed from the action, almost by force, by his bodyguard; they fled towards Toledo. The Castilian infantry was destroyed, together with most of the Orders which had supported them; the Lord of Vizcaya tried to force his way through the ring of enemy forces, but finally had to seek refuge in the unfinished fortress of Alarcos with just a fraction of his knights. The castle was surrounded with some 3,000 people trapped inside, half of them women and children. The king's enemy, Pedro Fernández de Castro, who had taken little part in the action, was sent by the Amir to negotiate the surrender; López de Haro and the survivors were allowed to go, leaving 12 knights as hostages for the payment of a great ransom.

The Castilian field army had been destroyed. Those killed included three bishops (from Avila, Segovia, and Siguenza);[3] Count Ordoño García de Roda and his brothers; Counts Pedro Ruiz de Guzmán and Rodrigo Sánchez; the Masters of the Order of Santiago, Sancho Fernández de Lemus, and of the Portuguese Order of Évora, Gonçalo Viegas. Losses for the Muslims included the death of the vizier and Abi Bakr, commander of the Bani Marin volunteers, who died of his wounds in the following year.

Aftermath

The outcome of the battle shook the stability of the Kingdom of Castile for several years. All nearby castles surrendered or were abandoned: Malagón, Benavente, Calatrava,[6] Caracuel, and Torre de Guadalferza, and the way to Toledo was wide open. However, Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur moved back to Seville to make good his own considerable losses; there he took the title of al-Mansur Billah ('The one victorious by God').

For the next two years, al-Mansur's forces devastated Extremadura, the Tagus valley, La Mancha and even the area around Toledo; they moved in turn against Montánchez, Trujillo, Plasencia, Talavera, Escalona and Maqueda. Some of these expeditions were led by the renegade Pedro Fernández de Castro. Most significantly, however, these raids did not lead to any territorial gains for the caliph, although Almohad diplomacy did obtain an alliance with King Alfonso IX of León (who had been enraged when the Castilian king had not waited for him before the battle of Alarcos) and the neutrality of Navarre. These alliances proved to be temporary only.

But the caliph was losing interest in the affairs of the Iberian Peninsula; he was in poor health, his objective of retaining a hold over al-Andalus appeared to be a complete success, and in 1198 he returned to Africa. He died in February 1199.

However, the success of the battle proved to be short-lived. When the Almohad caliph Muhammad al-Nasir attempted to build on it 16 years later with a new Iberian offensive, he was crushingly defeated in the more decisive Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa. This battle was to mark a turning-point that led to the end of Moorish rule in the Iberian Peninsula. The Almohad Empire itself collapsed a few years later.

References

Citations

- Battle of Alarcos, Theresa M. Vann, Medieval Iberia: An Encyclopedia, Ed. E. Michael Gerli and Samuel G. Armistead, (Taylor & Francis, 2003), 42.

- Britannica.com

- Medieval Iberia: an encyclopedia, 42.

- Abdelwahid al-Marrakushi "Al-Mojib fi Talkhis Akhbar al-Maghrib" [The Pleasant In Summarizing the History of the Maghreb" (1224), pp.136-137

- Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad Maqqarī, Ibn al-Khaṭīb, The history of the Mohammedan dynasties in Spain, (Johnson Reprint Corporation, 1843), lxv.

- King, Georgiana Goddard, A brief account of the military orders in Spain, (The Hispanic Society of America, 1921), 26.

Bibliography

- Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad Maqqarī, Ibn al-Khaṭīb, The history of the Mohammedan dynasties in Spain, Vol.2, Johnson Reprint Corporation, 1843.

- Britannica.com

- King, Georgiana Goddard, A brief account of the military orders in Spain, The Hispanic Society of America, 1921.

- Medieval Iberia: an encyclopedia, Ed. E. Michael Gerli and Samuel G. Armistead, Taylor & Francis, 2003.