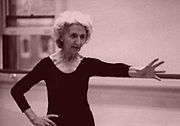

Irmgard Bartenieff

Irmgard Bartenieff (1900 Berlin – 1981 New York City) was a dance theorist, dancer, choreographer, physical therapist, and a leading pioneer of dance therapy. A student of Rudolf Laban, she pursued cross-cultural dance analysis, and generated a new vision of possibilities for human movement and movement training. From her experiences applying Laban’s concepts of dynamism, three-dimensional movement and mobilization to the rehabilitation of people affected by polio in the 1940s, she went on to develop her own set of movement methods and exercises, known as Bartenieff Fundamentals.[1]

Irmgard Bartenieff | |

|---|---|

Irmgard Bartenieff | |

| Born | February 24, 1900 Berlin, Germany |

| Died | August 27, 1981 New York City, United States |

| Occupation | physical therapist, movement analyst, researcher, dance therapist, writer |

| Notable works | Body movement - Coping with the environment (1980) |

Bartenieff incorporated Laban's spatial concepts into the mechanical anatomical activity of physical therapy, in order to enhance maximal functioning. In physical therapy, that meant thinking in terms of movement in space, rather than by strengthening muscle groups alone. The introduction of spatial concepts required an awareness of intent on the part of the patient as well, that activated the patient's will and thus connected the patient's independent participation to his or her own recovery. "There is no such thing as pure “physical therapy” or pure “mental” therapy. They are continuously interrelated."[2]

Bartenieff’s presentation of herself was quiet and, according to herself, she did not feel comfortable marketing her skills and knowledge. Not until June 1981, a few months before she died, did her name appear in the institute’s title: Laban/Bartenieff Institute of Movement Studies (LIMS), a change initiated by the Board of Directors in her honor.[3]

Biography

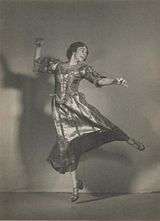

Irmgard Bartenieff (born February 24, 1900 in Berlin, Germany, d. August 27, 1981 in New York City) was a dancer, physical therapist, cross-cultural scholar and pioneer in the field of dance/movement therapy. A Renaissance woman who enjoyed weaving disciplines together, she was always ready to investigate movement in a variety of fields—including child development, ethnic dances, nonverbal communication and physical rehabilitation.

Laban

In her two-year program with Laban and his colleagues, Bartenieff studied Choreutics (Space Harmony) with Gertrude Loeser, Eukinetics (Effort) with Dussia Bereska, dance technique with Herman Robst and notation and composition with Laban.[4]

Between 1933 and 1936 when political restrictions in Germany limited her work, she made plans to emigrate. She and her second husband, who were Jewish, had a thriving dance company, but their dancers, threatened by the Nazis with expulsion from the union, were forced to resign. During the years when the company was disbanded, Bartenieff worked on modern and historical dance notations, constructing eighteenth-century dances recorded by Raoul Auger Feuillet. The Bartenieffs left Germany the first time for New York on visitor’s visas leaving her sons in the care of her family. The children left Germany in 1939 on the last peacetime ship before World War II began.[5]

Bartenieff brought the work of Laban and his colleagues to North America, where she created a setting for teaching and training the Laban theory. Furthermore she augmented Laban's work with what came to be known as Bartenieff Fundamentals™.

Polio Patients

Her first appointment in the United States was as Chief Physical Therapist for the Polio Service of New York City at Willard Parker Hospital. She combined her Laban-based understanding of movement with her physical therapy training in the clinical setting.

As Bartenieff observed her first polio patients she became intensely aware of their individuality in coping with the sudden loss of function and changes in self-image. "The unity of the functional and expressive aspects of movement behavior became increasingly clarified."[2] Both aspects had to be dealt with in the rehabilitation setting.

In the treatment process of polio, hot packs and hydrotherapy in Hubbard tanks was replacing bracing and casting. Passive stretching was also used to lengthen muscles that were developing contractures. "In stretching the stiff (polio) back, we found that by extending movement possibilities beyond forward flexion of the trunk to include lateral (sideward) flexion and rotation (twisting) we were able to establish full flexibility of the spine in all directions. We therefore moved the trunk passively in a sequence of lateral, rotary, flexion gradually into sitting up."[2] In this way the normal length of the back muscles was restored. Bartenieff described her method in an article in 1955[6] on this mobilizing technique that she taught in many hospitals.

From 1968, at Bellevue Hospital Center Bartenieff’s work involved cases of the control/restoration of movement patterns governed by the central nervous system rather than the treatment of peripheral problems in the affected muscles of polio patients (polio is a peripheral motor neuron disease). "My focus was on the restoration of Shaping (the body’s ability to adapt its form or shape) possibilities by restoring verticality, and the ability to support body-limb shaping from that verticality. This was in contrast to the more traditional focus on muscular activity without spatial reference."[2]

Handicapped Children

Seven years after her appointment at Willard Parker Hospital, she became chief therapist and coordinator of activity programs (1953–1957) at Blythedale Children's Hospital in Valhalla, New York under the direction of Dr. A.D. Gurewitsch. Blythedale was a small, private, residential treatment center for orthopedically and neurologically handicapped children (ages 5–14). Her job was to coordinate every aspect of the child’s long period of hospitalization that involved therapeutic, recreational and educational components.

To the physical handicaps of the children were added the emotional impact of “the climate of stasis and regression” of the hospital itself. The patients were removed from their normal growing experiences: "Imagination, initiative, social development was suspended... My task... was to find ways of keeping alive the movement impulse — the root of all development of a thinking, feeling, acting human being... and foster the emotional climate. I had to stimulate their natural action potential... innate curiosity, a desire to change, the discovery of alternate ways of functioning, relating to others, taking initiative, resisting, asserting—all in both physical and emotional modes—and especially, enjoying play."[2] This work led to developmental studies on newborns and infants at Long Island Jewish Hospital in collaboration with Dr. Judith Kestenberg.[7]

Connective Tissue Massage

Coincident with the Blythedale appointment, Bartenieff also worked at the Institute for the Crippled and Disabled. In this setting she learned connective tissue massage[5] and continued her work with a whole-body focus: "We tried to replace wherever possible—and that means medically feasible—the conventional type of localized exercise by total movement patterns based on dance fundamentals."[8]

Back to Study

While maintaining an active practice in physical therapy, Bartenieff resumed study with Laban and his colleagues in England in the 1950s. There she added to her knowledge of Laban’s Effort theory and the emerging Shape theory of Warren Lamb. Back in New York, she applied these ideas in her own physical therapy practice and set up training programs for dance therapists and other movement professionals.

Dance Therapy

She held a position of dance therapy research assistant (1957–1967)[8] to Dr. Israel Zwerling at the Day Hospital Unit of Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Zwerling, a psychiatrist [...] was very receptive to further exploration of dance as a therapeutic tool for defusing aggression and anxiety. What particularly reinforced his interest in her was that she had a vocabulary and a notation for recording observations of movement. This became a vital factor in daily observations through the one-way screen, especially of family and therapeutic groups.[2]

Dance therapy was then an emerging field of adjunctive therapy. Bartenieff’s special contribution was in bringing Laban’s work to a field very much in need of movement documentation: [It] provided a method of movement analysis and a system of notation which placed dance therapists on their own professional ground, giving them a language for describing patients’ movements, and eliminating the need to rely on less accurate jargon borrowed from other disciplines.[9]

Laban-based Training Program

In her sixty-fifth year Bartenieff established the first North American training program in Laban-based movement theory at the Dance Notation Bureau. It was known as the Effort/Shape Certification program. Students learned a means of observing and describing the qualitative and spatial aspects of movement which Laban and his colleagues in England had been using in various applications since the 1940s. In her own teaching, however, Bartenieff found her students lacking the whole body integration, or “connectedness” as she called it, necessary to fully experience the range of Effort qualities. Thus, as a remedial measure she began to teach classes in “correctives” which eventually came to be known as Bartenieff Fundamentals.

Choreometrics project

Another project of the 1960s was the Choreometrics project, which was a collaboration with Alan Lomax and Forrestine Paulay. This project took Bartenieff into cross-cultural studies of movement, expressed in work and dance activities. An educational film entitled “Dance and Human History” (1976)[10] demonstrates the concepts of the Choreometrics team.[11] This project was the first to adapt Laban-based movement analysis to observation of cultural/geographic differences. It is only one example of Bartenieff’s acute awareness of the differences among peoples of the world. In 1977–1978 she conducted a study of cross-cultural methods of movement fundamentals, presenting her findings in a major conference paper.[12] It was the first demonstration of Fundamentals to Bartenieff’s peers in dance research. These projects contributed significantly to the theoretical development of Effort/Shape and Fundamentals.

Laban Institute of Movement Studies (LIMS)

The Effort/Shape program outgrew its home at the Dance Notation Bureau, where the last year-long certificate program ran in 1977–1978. It was re-formed and relocated as the Laban/Bartenieff Institute of Movement Studies (LIMS). The founding board of directors created LIMS specifically as a place where Bartenieff, then in her seventy-eighth year, could continue her research, writing and teaching. In 1980 her book Body movement: coping with the environment, written with Dori Lewis, was published as a study of human movement from a whole-person perspective and a rich account of Bartenieff’s own experiences in movement work.

“Up to the last six months of her life, when she became ill, Bartenieff maintained a private physical therapy practice and lectured and taught around the country."[13]

She died on 27 August 1981[14] of complications from Raynaud’s disease.

Bartenieff Fundamentals

Bartenieff Fundamentals is not a system of set exercises. It is an approach to basic body training that deals with principles of anatomical body function within a context that encourages personal expression and full psychophysical functioning as an integral part of total body mobilization.[1]

Irmgard Bartenieff said, “Body movement is not a symbol for expression, it is the expression. Anatomical and spatial relationships create sequences of Effort rhythms with emotional concomitants. The functional and the expressive are one in the human being.”[15]

Bartenieff Fundamentals utilizes the entire Laban Movement Analysis (LMA) framework to develop movement efficiency and expressiveness. It emphasizes mobility process rather than muscle strength to achieve maximally efficient and expressive movement.[1]

For further details, see Bartenieff Fundamentals

References

- From an article by Hackney, P. published in Fitt, S. S. Dance Kinesiology (1996). Hackney, P. Schirmer/Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-0028645070

- Bartenieff, I., Lewis, D. Body movement - Coping with the environment (1980, 2002). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-677-05500-5

- "Tobin, S. Irmgard Bartenieff (2009). Courtesy of Association for Cultural Equity". Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- Groff, E. Laban Movement Analysis: an historical, philosophical, and theoretical perspective (1990). M.F.A. thesis, Connecticut College.

- Pforsich, J. and Diaz, M. A. Irmgard Bartenieff: personal history (1980). Audiotaped interview, 15 May. Laban/Bartenieff Institute of Movement Studies Library.

- Bartenieff, I. Functional approach to the early treatment of poliomyelitis (1955). Physical Therapy Review 35:12

- Bartenieff, I. and Davis, M. Effort-Shape analysis of movement: the unity of function and expression. Research approaches to movement and personality (1972). New York: Arno Press.

- Bartenieff, I. How is the dancing teacher equipped to do dance therapy? (1957). Music Therapy

- Levy, F. Dance movement therapy: a healing art (1988). Reston, VA: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance.

- Dance and Human History (1976). Motion Picture. Berkeley: University of California Extension Media Center, 40 min. color, 16mm, sound. Subject: The Choreometrics project of Lomax, Bartenieff and Paulay.

- Bartenieff, I. and Paulay, F. Research in anthropology: a study of dance styles in primitive cultures. (1967). In Research in dance, problems and possibilities. New York: Committee on Research in Dance.

- Bartenieff, I. and Lamb, T. Principles for studying the basis of movement in diverse cultures. (1978). Unpublished paper. CORD/ADG conference, Honolulu, HI, July. Laban/Bartenieff Institute of Movement Studies Library.

- Moore, C-L. Biography (1981). Laban/Bartenieff News, (December).

- Irmgard Bartenieff obituary (1981). Dance Magazine, November.

- Bartenieff, I. Body/Space/Effort: The Art of Body Movement as a Key Perception (1979). Unpublished Manuscript.

General references

- Folk Song Style and Culture. With contributions by Conrad Arensberg, Edwin E. Erickson, Victor Grauer, Norman Berkowitz, Irmgard Bartenieff, Forrestine Paulay, Joan Halifax, Barbara Ayres, Norman N. Markel, Roswell Rudd, Monika Vizedom, Fred Peng, Roger Wescott, David Brown. Washington, D.C.: Colonial Press Inc, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Publication no. 88, 1968.

- Kabat, H. Studies on neuromuscular dysfunction: XV. The role of central facilitation in restoration of motor function in paralysis. (1952). Archives of Physical Medicine 33: 521-33, (September).

- Laban, R. Modern educational dance (1975). Third edition. L. Ullmann, ed. London: Macdonald and Evans.

- Valvano, J. and Long, T. Neurodevelopmental treatment: a review of the writings of the Bobaths. (1991). Pediatric Physical Therapy 3:3 (Fall)

- Voss, D. E., Ionta, M. K. and Myers, B. J. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation: patterns and techniques (1985). Third edition. New York: Harper and Row.

- Woodruff, D. L. Bartenieff Fundamentals™: A somatic approach to movement rehabilitation (1992). The Union Institute. Dissertation placed with University Microfilms International.