Al Wakrah (municipality)

Al Wakrah Municipality (also spelled Al Wakra Municipality; Arabic: بلدية الوكرة Baladīyat al-Wakrah) is a municipality of Qatar located bordered by the municipalities of Doha and Al Rayyan. The municipal seat is Al Wakrah city.

Al Wakrah Municipality بلدية الوكرة | |

|---|---|

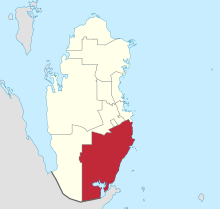

Map of Qatar with Al Wakrah highlighted | |

| Coordinates (Al Wakrah): 25°10′48″N 51°36′36″E | |

| Country | |

| Capital | Al Wakrah city |

| Zones | 7 |

| Government | |

| • Director | Mansour Ajran Al-Buainain |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 2,577.7 km2 (995.3 sq mi) |

| Population (2015)[1] | |

| • Municipality | 299,037 |

| • Density | 120/km2 (300/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+03 (East Africa Time) |

| ISO 3166 code | QA-WA |

Etymology

The municipality was named after the city of Al Wakrah, which derives its name from the Arabic word "wakar", which roughly translates to "bird's nest". According to the Ministry of Municipality and Environment, this name was given in reference to a nearby hill which accommodated the nests of several birds.[2]

History

On 17 July 1972, the creation of the municipalities of Ar Rayyan, Al Wakrah, Al Khawr and Thakhira, Al Shamal, and Umm Salal were issued. This law identified Al Wakrah Municipality as a legal district.[3] The municipal board has a president and four members. The current president of the Municipal board is Mansour Ajran Al-Buainain.[4]

Geography

The southern end Al Wakrah is characterized by dense sand sheets sand dunes. Unlike northern Qatar where most areas lie close to sea level, much of the southern and central portions of Al Wakrah are at elevations of 40 to 60 meters above sea level. Water is scarce in most areas as the water table is relatively low. Although there are some rawdas (depressions), they are rare when compared to northern Qatar. Furthermore, the southern groundwater is often saline. As a result, permanent settlements were far and few between, with some exceptions being found at Al Kharrara, Traina and Al Furayah north of Khawr al Udayd.[5]

Many nomadic camps were created in Al Wakrah's south in past times; these sites can often be identified by the presence of small, open mosques. It is likely that Bedouins visited the region mainly during times of suitable weather, such as the rainy season. Herdsman were able to nourish their camels with the saline water, which would, in turn, yield drinkable milk.[5]

According to the Ministry of Municipality and Environment (MME), the municipality accommodates 192 rawdas, 13 wadis, four jeris (places where water flows), seven plains, 14 hills, four highlands, seven sabkhas, four bays, and three coral reefs. The only cape recorded here is Ras Al Maharef. Two islands are found off its shores: Sheraouh Island and Al Aszhat Island.[6] One of the most prominent of its hills is Jebel Al Wakrah, an 85-feet high rocky hill located one mile south of the city of Al Wakrah.[7] The Naqiyan Hill Range dominates the southern quarter of the municipality in Khawr al Udayd.[8]

Protected areas

The UNESCO-recognized Khawr al Udayd is Qatar's largest nature reserve and is located on the south-east corner of the municipality.[9] Also known by its English name Inland Sea, the area was declared a nature reserve in 2007 and occupies an area of approximately 1,833 km².[10] Historically, the area was used for camel grazing by nomads, and is still used for the same purpose to a lesser extent. Various flora and fauna are supported in its ecosystem, such as ospreys, dugongs and turtles. Most notable is the reserve's unique geographic features. The appearance and the quick formation of its sabkhas is distinct from any other system of sabkhas, as is the continuous infilling of its lagoon.[11]

Climate

The following is climate data for the city of Mesaieed, south of the capital Al Wakrah City.

| Climate data for Mesaieed | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 20 (68) |

22 (72) |

25 (77) |

30 (86) |

36 (97) |

38 (100) |

38 (100) |

37 (99) |

34 (93) |

32 (90) |

27 (81) |

20 (68) |

30 (86) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 11 (52) |

12 (54) |

15 (59) |

18 (64) |

23 (73) |

25 (77) |

26 (79) |

27 (81) |

24 (75) |

21 (70) |

17 (63) |

11 (52) |

19 (67) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 10 (0.4) |

2 (0.1) |

2.5 (0.10) |

6 (0.2) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.5 (0.02) |

13.5 (0.53) |

24 (0.9) |

59.5 (2.25) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 66 | 55 | 51 | 43 | 41 | 48 | 62 | 60 | 64 | 65 | 70 | 58 |

| Source: Qatar Statistics Authority[12] | |||||||||||||

Administration

Al Wakrah Municipality was established in 1972 and supervises the city of Al Wakrah in addition to other settlements in the municipality. The municipality has four sections: Financial and Administrative Affairs Section, Health Affairs Section, General Affairs Section and the Technical Affairs Section.[3] Al Thumama is geographically located in both Al Wakrah Municipality and Doha Municipality.[2]

The municipality is divided into 7 zones which are then divided into 1410 blocks.[14]

Administrative zones

The following administrative zones are found in Al Wakrah Municipality:[1]

| Zone no. | Settlements | Area (km) | Population (2015) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | Al Wakrah | 75.8 | 87,970 |

| 91 | Al Thumama Al Wukair Al Mashaf | 203.4 | 165,214 |

| 92 | Mesaieed | 133.2 | 37,548 |

| 93 | Mesaieed Industrial Area | 60.7 | 106 |

| 94 | Shagra | 497.2 | 4,714 |

| 95 | Al Kharrara | 902.4 | 3,478 |

| 98 | Khawr al Udayd | 705 | 7 |

| Municipality | 2577.7 | 299,037 | |

Districts

Other settlements in Al Wakrah include:[15]

- Abu Sulba (Arabic: بو صلبة)

- Al Afja Mesaieed (Arabic: العفجة مسيعيد)

- Barwa Al Baraha (Arabic: بروة البراحة)

- Birkat Al Awamer (Arabic: بركة العوامر)

- Muaither Al Wukair (Arabic: معيذر الوكير)

- Ras Abu Fontas (Arabic: راس بو فنطاس)

- Traina (Arabic: ترينة)

- Umm Al Houl (Arabic: ام الحول)

- Umm Besher (Arabic: ام بشر)

- Wadi Aba Seleel (Arabic: وادي ابا الصليل)

- Wadi Jallal (Arabic: وادي جلال)

Education

Public schools in Al Wakrah amounted to 19 in 2016 as recorded in that year's education census – 9 were exclusively for girls and 10 were for boys. Male students (4,017) slightly outnumbered the 3,993 female students.[16]

Healthcare

According to the 2015 government census, there were 4 registered healthcare facilities in the municipality.[17] Primary healthcare centers are located in Al Wakrah City[18] and Al Thumama.[19] Al Wakrah Hospital was established in 2012 and serves the southern region of the country. It is based in Al Wakrah City and is the largest hospital building in Qatar.[20]

Eleven pharmacies were recorded in the municipality in 2013 by Qatar's Supreme Council of Health.[21]

Economy

Mesaieed Industrial Area, an industry hub, is located in Al Wakrah Municipality.[22] Umm Al Houl, another industrial city located in the municipality which is near to Mesaieed, hosts Qatar's main seaport Hamad Port,[23] and is the site of construction for what will eventually be Qatar's largest electricity and desalination plant.[24] A third industrial area containing some of Qatar's most important power stations and desalination plants is Ras Abu Fontas.[25]

A 6.3 km² "regional logistics hub" was launched in the southern portion of the municipality in 2016. The development of this hub will take place in Birkat Al Awamer and Aba Saleel, which are in close proximity to Hamad Port and Mesaieed Industrial Area. Among the facilities in this hub will be car workshops, labor camps, and commercial offices.[26] Construction of the hub will be managed by Qatari company Manateq.[27] The Doha Marketing and Services Company established a car stockyard in Birkat Al Awamer with a capacity of 1,700 cars in September 2016.[28]

Maritime industries such as fishing and pearling comprised the economic foundation of Al Wakrah's coastal settlement in the past.[29] Further inland, nomadic pastoralism dominated.[30] At present, agriculture plays only a minor role in Al Wakrah's economy. Farmland in Al Wakrah only accounted for 4.6% of Qatar's total farmland in 2015. There were 71 farms spread out over 2,188 hectares, with the majority (38) being used to grow crops, 3 being used to raise livestock and the remaining 30 being split between livestock and crops.[31] The municipality had a livestock inventory of 14,946, of which 8,375 were sheep and 6,093 were goats.[32]

In terms of artisanal fishing vessels, Al Wakrah city had the second-highest amount out of the major cities surveyed in 2015 at 179 vessels. However, its fleet has been significantly reduced from earlier years, for earlier in 2010 it had accommodated the most fishing vessels out of all cities surveyed with 237 vessels. The number of sailors was 1,186 in 2015, but this figure too had been decreasing over the years.[33]

Sports

Qatar Stars League team Al-Wakrah SC, founded in 1959, is based in Al Wakrah City.[34] They club plays its home games at the 12,000 capacity Saoud bin Abdulrahman Stadium.[35]

One of the proposed twelve venues for the 2022 FIFA World Cup is projected to be built in Al Wakrah City. Called Al Wakrah Stadium, it has a planned seating capacity of 40,000 and will replace Saoud bin Abdulrahman Stadium as Al Wakrah SC's home stadium.[36]

Visitor attractions

Due to the unique ecosystem and landscape of Khawr al Udayd, it serves as one of the most important ecotourism site in the country.[37]

Sealine Beach Resort, located on the coast in Mesaieed, was the first tourist resort to be established in the country.[38] The resort has 37 rooms, 1 hectare of green space, a gym, a spa and 95 square meter multi-purpose hall.[39]

According to the Ministry of Municipality and Environment, the municipality accommodates 6 parks as of 2018.[40]

Demographics

The following table is a breakdown of registered live births by nationality and sex for Al Wakrah. Places of birth are based on the home municipality of the mother at birth.[41]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- "2015 Population census" (PDF). Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. April 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "District map". The Centre for Geographic Information Systems of Qatar. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "Al Wakrah Municipality". Ministry of Municipality and Environment. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Ashghal announces the completion of 4 roads and infrastructure projects in Al Wakra Municipality". qatarisbooming.com. 19 January 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Phillip G. Macumber (2015). "Water Heritage in Qatar" (PDF). Cultural Heritages of Water: Thematic Study on The Cultural Heritages of Water in the Middle East and Maghreb. UNESCO World Heritage Convention. UNESCO. p. 235. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "Geonames Sortable Table". arcgis.com. Geographic Information Systems Department (Qatar). Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- The Persian Gulf pilot: comprising the Persian Gulf, Gulf of Omán; and Makran coast. Great Britain: Hydrographic Dept. 1890. p. 122.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol. II. Geographical and Statistical. J G Lorimer. 1908' [1509] (1624/2084)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Anisha Bijukumar (15 April 2017). "Approx 23 per cent of Qatar area is nature reserve". The Peninsula. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- "Khor Al Adaid Reserve". Qatar eNature. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- "Khor Al-Adaid natural reserve". UNESCO. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- "Temperature/Humidity/Rainfall". Qatar Statistics Authority. Archived from the original on 2013-03-22. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- "District map". The Centre for Geographic Information Systems of Qatar. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Administrative boundary map". Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- "Qatar Development Atlas - Part 1" (PDF). Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. 2010. p. 10. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- "Chapter IV: Education Statistics" (PDF). Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- "The Simplified Census of Population, Housing & Establishments 2015" (PDF). Ministry of Municipality and Environment. April 2015. pp. 65–66. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "Al Wakra HC". Primary Health Care Corporation. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Al Thumama HC". Primary Health Care Corporation. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Al Wakra Hospital - About". Hamad Medical Corporation. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Qatar Healthcare Facilities: Master Plan 2013-2033" (PDF). Supreme Council of Health (Qatar). September 2014. p. 107. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Turloch Mooney (19 April 2017). "Gulf ports set for consolidation, says Sohar CEO". Fairplay. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Kim Kemp (2 March 2015). "Hamad Port will become fully operational in 2016". Construction Week Online. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Peter Kovessy (25 May 2015). "Consortium to build Qatar's largest power and desalination plant". Doha News. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- "ACCIONA takes part in the opening ceremony of the construction work for its first desalination plant in Qatar". ACCIONA. 11 December 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "Qatar announces regional logistics hub". Freight Week. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- "Wheels of Progress". The Business Year. 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- "Domasco opens new stockyard". Gulf Times. 5 September 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- "Al-Wakrah". Abbey Travel. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- Mohammed Jassim Al-Maslamani (December 2008). "Assessment of Atmospheric Emissions Due to Anthropogenic Activities In The State Of Qatar (PHD Thesis)". Institute for the Environment at Brunel University: 33. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.427.2056. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Environmental statistics in State of Qatar" (PDF). Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. 2015. p. 30. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Environmental statistics in State of Qatar" (PDF). Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. 2015. p. 38. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Environmental statistics in State of Qatar" (PDF). Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. 2015. p. 84–85. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Al Wakrah Club". Qatar Football Association. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Saoud Bin Abdulrahman Stadium (Al-Wakrah Stadium)". Soccerway. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Al Wakrah Stadium". Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Khor Al Adaid". Qatar Tourism Authority. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Sealine Beach Resort get a facelift; showcases new facilities". The Peninsula. 23 February 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Sealine Beach Resort Hotel". Qatar Tourism Authority. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "تطور غير مسبوق في تصميم وإنشاء الحدائق العامة بالدولة" (in Arabic). Ministry of Municipality and Environment. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Home page". Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1984" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). September 1985. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1985" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). June 1986. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1986" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). June 1987. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1987" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). June 1988. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1988" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). June 1989. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1989" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). May 1990. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1990" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). May 1991. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1991" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). June 1992. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1992" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). June 1993. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1993" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). April 1994. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1995" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). May 1996. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1996" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). June 1997. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1997" (PDF). Central Statistical Organization (Qatar). June 1998. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1998" (PDF). The Planning Council of the General Secretariat. June 1999. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 1999" (PDF). The Planning Council of the General Secretariat. July 2000. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 2000" (PDF). The Planning Council of the General Secretariat. April 2001. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 2001" (PDF). The Planning Council of the General Secretariat. June 2002. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 2002" (PDF). The Planning Council of the General Secretariat. June 2003. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 2003" (PDF). The Planning Council of the General Secretariat. April 2004. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 2004" (PDF). The Planning Council of the General Secretariat. June 2005. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 2005" (PDF). The Planning Council of the General Secretariat. September 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 2006" (PDF). Qatar Statistics Authority. August 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 2007" (PDF). Qatar Statistics Authority. July 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 2008" (PDF). Qatar Statistics Authority. 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births & Deaths): 2009" (PDF). Qatar Statistics Authority. July 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Al Wakrah. |