Zubarah

Zubarah (Arabic: الزبارة), also referred to as Al Zubarah or Az Zubarah, is a ruined and ancient fort located on the north western coast of the Qatar peninsula in the Al Shamal municipality, about 105 km from the Qatari capital of Doha. It was founded by Shaikh Muhammed bin Khalifa, the founder father of Al Khalifa royal family of Bahrain, the main and principal Utub tribe in the first half of the eighteenth century.[1][2][3][4][5] It was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2013.[6]

Zubarah الزبارة Al Zubarah Az Zubarah | |

|---|---|

Ruined Town | |

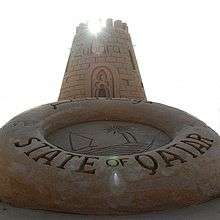

The iconic Zubarah Fort found in Zubarah. | |

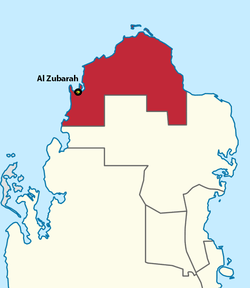

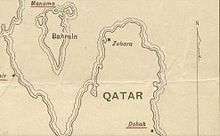

Geographical location of Zubarah. | |

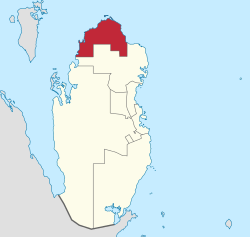

Al Shamal in Qatar. | |

Zubarah Geographical location of Zubarah. | |

| Coordinates: 25°58′43″N 51°01′35″E | |

| Country | Qatar |

| Municipality | Al Shamal |

| Zone no. | 78 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.6 km2 (1.8 sq mi) |

| • Land | 4 km2 (2 sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Zubaran Al Zubaran |

| Official name | Al Zubarah Archaeological Site |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 2013 (37th session) |

| Reference no. | 1402 |

| State Party | Qatar |

| Region | Western Asia |

It was once a successful center of global trade and pearl fishing positioned midway between the Strait of Hormuz and the west arm of the Persian Gulf. It is one of the most extensive and best preserved examples of an 18th–19th century settlement in the region. The layout and urban fabric of the settlement has been preserved in a manner unlike any other settlements in the Persian Gulf, providing an insight into the urban life, spatial organization, and the social and economic history of the Persian Gulf before the discovery of oil and gas in the 20th century.[7]

Covering an area of circa 400 hectares (60 hectares inside the outer town wall), Zubarah is Qatar’s most substantial archaeological site. The site comprises the fortified town with a later inner and an earlier outer wall, a harbour, a sea canal, two screening walls, Qal'at Murair (Murair fort), and the more recent Zubarah Fort.[8]

History

Early history

Zubarah, derived from the Arabic word for 'sand mounds', was presumably given its name due its abundance of sand and stony hillocks.[9] During the early Islamic period, trade and commerce boomed in northern Qatar. Settlements began to appear on the coast, primarily between the towns of Zubarah and Umm Al Maa. A village dating back to the Islamic period was discovered near the town.[10]

Between September 1627 and April 1628, a Portuguese naval squadron led by D. Goncalo da Silveira set a number of neighboring coastal villages ablaze. Zubarah's settlement and growth during this period is attributed to the dislodging of people from these adjacent settlements.[11]

Arrival of Al Khalifa of Utub tribe

There remains some uncertainty over the earliest mention of Zubarah in written documents. Qatar's Memorial, a 1986 Arabic history book, alleges that a functional self-governing town existed before the arrival of the Utub.[12][13] It supported this claim by invoking two purported historical documents, but they were later discovered to be forgeries produced by Qatar in an attempt to gain leverage over Bahrain in their long-standing dispute over the sovereignty of the town.[12]

Zubarah was founded and ruled by the Al Khalifa branch of Utub tribe,[2][3][1][4][5] whom have migrated from Kuwait to Zubarah in 1732,[14] helping to build a large town characterized by a safe harbour. It soon emerged as one of the principal emporiums and pearl trading centres of the Persian Gulf.[15][16][17]

Al Khalifa rule of Zubarah

The Al Khalifa, migrated from Kuwait and settled at Zubarah in 1732,[14] founded and ruled the town of Zubarah,[2][3][1][4][5] and its port making it one of the most important port and pearl trading centers in the Persian Gulf in the 18th Century. They also expanded their settlements, and constructed walls and a fort outside the town of Zubarah called Qal'at Murair (Murair Castle), the name is derived from a water spring in the Bani Sulaim area next to Madina Al Munawara in today's Saudi Arabia also known as Herat Bani Sulaim.

The Al Khalifa were the original dominant group controlling the town of Zubarah on the Qatar peninsula, they were a politically important group that moved backwards and forwards between Qatar and Bahrain,[18][19] originally the center of power of the Bani Utbah. The Al Bin Ali, another branch of Bani Utbah, were also known for their courage, persistence, and abundant wealth.[20]

Under their jurisdiction, the town developed trade links with India, Oman, Iraq and Kuwait. Many goods were transported through its ports, including dates, spices and metals.[21] The town soon became a favorite transit point for traders after the Utub abolished trade taxes. The town's prosperity further increased after the 1775–76 Persian occupation of Basra when merchants and other refugees fleeing from Basra settled in Zubarah.[22] Among these merchants was Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Husain ibn Rizq, participated in the administration the town for a period. He had requested his personal biographer, Uthman ibn Sanad al-Basri, to come to the town with him in order to serve as the supreme judge. Al-Basri's biography, first published in 1813, provides the reader with much information pertaining to the development of the town under ibn Rizq's administration. He also makes note of several prominent scholars who migrated to the town, such as Abd al-Djalil al-Tabatabai.[23]

Inhabitants from nearby settlements, including wealthy merchants, migrated to Zubarah en masse during the 1770s due to the prevalence of attacks and the plague in the Persian Gulf region.[24] Ongoing wars between Bani Khalid and the Wahhabis was also a contributing factor that helped Al Zubara flourish into an important trade center.[25] This prominent position led to conflicts with adjacent port towns.[25]

1783 Al Khalifa expansion to Bahrain

A quarrel arose in 1782 between the inhabitants of Zubarah and Persian-ruled Bahrain. Zubarah natives traveled to Bahrain to buy some wood, but an altercation broke out and in the chaos an Utub sheikh's slave was killed. The Utub and other Arab tribes retaliated on 9 September by plundering and destroying Manama.[22] A battle was also fought on land between the Persians and the Arab tribes, in which both sides suffered casualties. The Zubarans returned to the mainland after three days with a seized Persian gallivat that had been used to collect annual treaty. On 1 October, 1782, Ali Murad Khan ordered the sheikh of Bahrain to prepare a counter-attack against Zubarah and sent him reinforcements from the Persian mainland.[26]

About 2,000 Persian troops arrived in Bahrain by December 1782; they then attacked Zubarah on 17 May 1783. After suffering a defeat, the Persians withdrew their arms and retreated to their ships. An Utub naval fleet from Kuwait arrived in Bahrain the same day and set Manama ablaze. The Persian forces returned to the mainland to recruit troops for another attack, but their garrisons in Bahrain were ultimately overrun by the Utub.[26]

It is well known that the strategist of this battle was Shaikh Nasr Al-Madhkur, his sword fell into the hands of Salama Bin Saif Al Bin Ali after his army collapsed and his forces were defeated.[27]

The Alkhalifa conquered and expelled the Persians from Bahrain[28] after defeating them. After the invasion, the Al Khalifa migrated to Bahrain, with Zubarah remaining under their jurisdiction.[29] The Bani Utbah was already present at Bahrain at that time, settling there during summer season and purchasing date palm gardens.

Despite the instability surrounding Zubarah after the siege of Zubarah and the conquest of Bahrain in 1783, it flourished as a trading centre and its port grew to be larger than that of Qatif's by 1790.[29] Al Zubarah developed into a center of Islamic education during this century.[30][31]

The town came under threat from 1780 onward due to the intermittent raids launched by the Wahhabi on the Bani Khalid strongholds in nearby al-Hasa.[32] The Wahhabi speculated that the population of Zubarah would conspire against the regime in Al-Hasa with the help of the Bani Khalid. They also believed that its residents practiced teachings contrary to the Wahhabi doctrine, and regarded the town as an important gateway to the Persian Gulf.[33] Saudi general Sulaiman ibn Ufaysan led a raid against the town in 1787. In 1792, a massive Wahhabi force conquered Al Hasa, forcing many refugees to flee to Zubarah.[32][34] Wahhabi forces besieged Zubarah and several neighboring settlements two years later to punish them for accommodating asylum seekers.[32] The local chieftains were allowed to continue carrying out administrative tasks but were required to pay a tax.[35]

Communal life

Zubarah was at that time a well-organised town, with many of the streets running at right angles to one another and some neighbourhoods built according to a strict grid pattern. This layout suggests that the town was laid out and built as part of a major event, although seemingly constructed in closely dated stages.[36] An estimate of the population at the height of the town has been calculated to a maximum number of between 6,000 and 9,000 people.[8]

Most of the settler's dietary requirements were fulfilled from the consumption of livestock animals. Remnants of sheep, goat, birds, fish and gazelle were among the waste collected from the palatial compounds.[37] The wealthiest members of the community consumed mainly livestock, whereas the poorer residents relied on fish as their primary source of protein.[38] Social, economic and political activity was most likely centered in the souq.[37] The discovery of numerous ceramic tobacco pipe bowls indicate a reluctant acceptance and growing social addiction to smoking tobacco. Coffee pots, mainly of Chinese origin, were used by Zubarah's inhabitants to drink Arabic coffee.[37]

Later developments and decline (19th century)

.png)

The town was occupied by the Wahhabi in 1809.[9] After the Wahhabi amir was made aware of advancements by hostile Egyptian troops on the western frontier in 1811, he reduced his garrisons in Bahrain and Zubarah in order to re-position his troops. Said bin Sultan of Muscat capitalized on this opportunity and attacked the Wahhabi garrisons in the eastern peninsula. The Wahhabi fortification in Zubarah was set ablaze and the Al Khalifa were effectively returned to power.[39][40] Following the attack, the town was abandoned for a short period. However, later archaeological discoveries indicate that the town may have been partially abandoned shortly before the 1811 attack.[9]

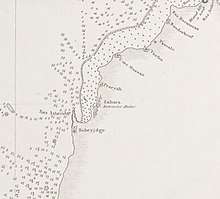

From c. 1810 onwards, the British Empire became more influential in the Persian Gulf area, stationing political agents in various ports and cities to protect their trading routes.[41] In one of the first descriptions of the salient towns in Qatar, Major Colebrook described Zubarah as such in 1820:[42]

- "protected by a tower and occupied at present merely for the security of fishermen that frequent it. It has a Khor (creek) with three fathoms water which Buggalahs may enter."

Captain George Barnes Brucks also gave his own account of Zubarah just four years later. He stated:[43]

- "(it was) a large town, now in ruins. It is situated in a bay, and has been, before it was destroyed, a place of considerable trade."

Zubarah was eventually resettled in the late 1820s. It remained a pearl fishing community, but on a significantly smaller scale than previously.[39] The reconstructed town barely covered 20% of its predecessor. A new town wall was constructed much closer to the shore than the earlier town wall. This phase of Zubarah was not as organized in the layout of the streets and its buildings. Houses were still built in the traditional courtyard form, but on a smaller scale and more irregular in their shape. Additionally, evidence of decorated plaster known from earlier buildings were not found in the newly constructed buildings.[44]

In 1868, the Al Khalifa launched a major naval attack on the eastern portion of Qatar. In the aftermath of this attack, a sovereignty treaty was signed between the Al Thani and the British, uniting the entire Qatari Peninsula under the leadership of the Al Thani. Nearly all of the authority that the Al Khalifa held in Zubarah was diminished, with the exception of informal treaties they had signed with a few local tribes.[45]

Al Khalifa contention

On 16 August 1873, assistant political resident Charles Grant falsely reported that the Ottomans had sent a contingent of 100 troops under the command of Hossein Effendi from Qatif to Zubarah. This report incensed the emir of Bahrain, as he had previously signed a treaty with the Naim tribe residing in Zubarah in which they agreed be his subjects, and the report implied that the Ottomans were encroaching on his territory. Upon being questioned by the emir, Grant referred him to political resident Edward Ross. Ross informed the sheikh that he believed he had no right to protect tribes residing in Qatar.[46] In September, the emir reiterated his sovereignty over the town and the Kubaisi and naim tribe. Grant replied by arguing that there was no special mention of the Kubaisi and naim or Zubarah in any British treaties signed with Bahrain. A government official agreed with his views and concurred "that it was desirable that the Chief of Bahrain should, as far as practicable abstain from interfering in complications on the mainland."[47]

The Al Khalifa witnessed another opportunity to renew their claim on the town in 1874 after a Bahraini opposition leader named Nasir bin Mubarak moved to Qatar. They believed that Mubarak, with the assistance of Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani, would attack the Kunaisi,s living in Zubarah as a prelude to an invasion of Bahrain. As a result, a body of Bahraini reinforcements were sent to Zubarah, much to the disapproval of the British who suggested that the emir was involving himself in complications. Edward Ross made it apparent that a government council decision advised the sheikh that he should not interfere in the affairs of Qatar.[48] However, the Al Khalifa remained in frequent contact with the Naim, drafting 100 members of the tribe in their army and offering them financial assistance.[49]

In September 1878, a number of Zubarans were involved in an act of piracy on a passing boat which resulted in the death of four people. Political resident Edward Ross demanded that the Ottoman authorities punish the townspeople for the crime, and extended an offer of British naval assistance. He held a meeting with wāli Abdullah Pasha in Basra to finalize the deal. Shortly after the British-Ottoman meeting, Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani and Nasir bin Mubarak attacked Zubarah with a force of 2,000 armed men. By 22 October, Jassim bin Mohammed's army, having sacked the town, now surrounded Murair Fort, which was fortified by 500 members of the Kubaisi tribe. The Kubaisi eventually surrendered to Jassim bin Mohammed's forces on unfavorable terms and most of the Zubarah's residents were relocated to Doha.[50][51] The incident aggravated the ruler of Bahrain due to his treaty with the Kubaisi tribe. There were reports in 1888 that Jassim intended to restore the city so that it could serve as a base for his son-in-law to attack Bahrain, but he renounced his plans after being warned by the British.[52]

Re-settlement of Al Bin Ali at Zubarah in 1895

At the request of Jassim bin Mohammed, several members of the Al Bin Ali, an Utub tribe, relocated from Bahrain to Zubarah in 1895 after renouncing their allegiance to the Bahraini sheikh. The Bahraini sheikh, fearful that Jassim bin Mohammed was preparing to launch an invasion, issued a warning to him and informed the political resident in Bahrain of the dispute. Upon being made aware of the proceedings, the British requested the Ottomans, who had been acting in concert with Jassim bin Mohammed, to abort the settlement. Much to the indignation of the Ottomans, the British sent a naval ship to Zubarah shortly after and seized seven of the Al Bin Ali's boats after the tribe's leader refused to comply with their directive. The Ottoman governor of Zubarah, under the belief that the British were infringing on Ottoman dominion, relayed the events to the Ottoman Porte who began assembling a large army near Qatif. Jassim bin Mohammed also congregated a large number of boats near the coast.[53] Subsequently, the governor of Zubarah declared Bahrain as Ottoman territory and threatened that the Porte would provide military support to Qatari tribes who were preparing to launch a naval invasion. This invoked a harsh reprisal from Britain, who, after issuing a written notice, opened fire on Zubarah's port, destroying 44 dhows. The incursion and subsequent Ottoman retreat prompted Jassim bin Mohammed and his army to surrender on unfavorable terms in which he was instructed to hoist the Trucial flag at Zubarah.[54] He was also ordered to pay 30,000 rupees.[55]

Abandonment (20th and 21st century)

With its population already depleted, much of the remaining population migrated to other regions in Qatar in the early 20th century due to the inadequate water supply in the town.[38]

J.G. Lorimer's Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf gives the following account of Zubarah in 1908:

"A ruined and deserted town on the west side of the Qatar Promontory, about 5 miles south of Khor Hassan. It stands at the foot of a deep bay of the same name, of which the western point is Ras 'Ashairiq and which contains a small island, also called Zubarah . The town was formerly the stronghold of the Al Khalifah ruling family of Bahrain : its site is still frequented by the Na'im of Bahrain and Qatar. The town was walled and some 10 or 12 forts stood within a radius of 7 miles round it, among them Faraihah, Halwan, Lisha, 'Ain Muhammad, Qal'at Murair, Rakaiyat, Umm-ash-Shuwail and Thaghab [...]. All of these are now ruinous and deserted, except Thaghab, which the people of Khor Hassan visit to draw water. Murair is said to have been connected with the sea by a creek which enabled sailing boats to discharge their cargoes at its gate, but the inlet is now silted up with sand."[56]

In 1937, a conflict broke out between Qatari loyalists and the Naim tribe who had defected to Bahrain, precipitating Bahrain's subsequent territorial claims to Zubarah. A recent proposal that Zubarah become an oil terminal was a contributing factor in the conflict.[57] Qatar's emir, Abdullah bin Jassim, referred to the Bahraini claim on Zubarah as "imaginary" and "not based on logic".[58] He also alleged that Bahrain provided assistance to the Naim in the form of arms and finances.[59] That year, in the aftermath of the conflict and subsequent out-migration, Abdullah bin Jassim commenced the construction of Zubarah Fort to compensate for the reduced garrison. It was completed in 1938.[60] Qal'at Murair, the hitherto principal fort of the town, was abandoned soon after Zubarah Fort was erected.[61]

In the mid 20th century, the political adviser in Bahrain, Charles Belgrave, reported that just a few Bedouin of the Nua‘imi (Naim) tribe lived, albeit nomadically, in the ruined town.[61] The area was gradually abandoned towards the end of the 20th century and was used primarily for beach camps.[62] The fort also housed a coast guard station until the 1980s.[63]

Geography

Zubarah encompasses a 400 hectare stretch the north western coast of the Qatar peninsula, and is located approximately 105 km from the Qatari capital Doha. It is situated over a low, coastal hillock. The two main habitat types are the sabkha and the stony desert. Historically, fresh water was of scarce availability. In an attempt to amass a water supply, Murair Fort was constructed 1.8 km eastward of the original settlement, on the margins of the desert scarp. The fort served to facilitate wells which tapped the shallow freshwater lenses.[64]

Holocene deposits are densely scattered in the sabkha and mud plain areas located near the city ruins and the sea. Most of the buildings in Zubarah were constructed using materials from these deposits. An area encompassing the city ruins and the project, which is labelled a proto-sabkha habitat, also contains large quantities of holocene fossils. Eocene limestone are predominant further inland where the habitat is a stony, arid desert.[65]

Zubarah Beach is located near the archaeological site, but is open only to those on guided tours.[66]

Flora and fauna

Vegetation in Zubarah is sparse, although three of the most recurrent species of seagrasses in the Persian Gulf have been collected and recorded in the area. This includes Halophila ovalis, Halophila stipulacea and Halodule uninervis.[65]

A total of c. 48 fish species, 40 mollusc species, 17 reptile species, and 170 arthropod species were recorded in the expanse of the town.[65] A preliminary investigation of Zubarah uncovered four previously unknown species of tardigrades.[65] Eleven species of Heterotardigrada, a class of the tardigrade, have been found to occur in the area.[65] Spiny-tailed lizards are the most prominent reptile species in the area. They are commonly spotted on vegetation. Mesalina brevirostris, a species of short-nosed lizard, is another reptile species which is densely scattered throughout the area.[65]

Economic history

Pearling activities

Zubarah was primarily an emporium and pearling settlement that capitalized on its proximity to pearl beds, possession of a large harbour and its central position on the Gulf routes. Its economy depended on the pearl diving season, which took place during the long summer months. Pearling would draw Bedouin from the interior of Qatar as well as the people from all over the Persian Gulf to dive, trade and safeguard the town from attack while the town’s men were at sea.[67][68]

Boats from Zubarah would sail out to the pearl beds found all along the southern shore of the Persian Gulf, from Bahrain to the United Arab Emirates. The trips lasted several weeks at a time. Men would work in pairs to harvest mollusks potentially hiding pearls inside them. A man would dive for about a minute and the other remained on the ship to pull the diver back to safety with his harvest.[67][68]

The archaeological evidence for pearling on site comes primarily from the tools used by the divers such, as pearl boxes, diving weights, and small measuring weights used during trading.[69]

Global trade

Zubarah was the focal point of an extensive regional trade network during its peak in the late eighteenth century.[70] Until the introduction of the cultured pearl in the early 1900s, the trade in pearls constituted the Persian Gulf’s most important industry, employing up to a third of the male population in the region. Zubarah, being one of the focal pearling and trading towns, contributed to the geopolitical, social, and cultural trajectories of Gulf history which shape the region today.[71][72]

Ceramics, coins, and the remains of foodstuffs from the excavations attest to Zubarah’s far reaching trade and economic links in the late 18th century, with material deriving from eastern Asia, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, Africa, Europe, and the Persian Gulf. Diving weights and other material culture show how closely the connection between the daily life in the town and the pearl fishing and trading were. The discovery of coffee cups and tobacco pipes in the excavations reveal the growing importance of these commodities all over the Persian Gulf during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The etching of a merchant’s dhow, the traditional wooden boat of Arabia, found incised into the plaster in a room of a courtyard building, details how intimately the town's inhabitants associated their daily lives with long-distance maritime trade and commerce.[71][72] Date trade also had an important role in the local economy.[37]

Marketplace

A complex array of small storage rooms have been identified as part of the souq (market) of Zubarah. The wide variety of trade objects that have been found in the rooms points towards the area's classification as a place of trade. The souq would have been the centre of the town and of its economy.[73] Various commodities, including ironsmithing, were sold at this souq.[9]

Historical architecture

Infrastructure

The architecture consisted mainly of courtyard houses, a traditional form of Arabic architecture which can be found throughout the Middle East. A series of small rooms were organized around a large central courtyard, where the majority of daily activity took place. Typically, a portico opened out onto the courtyard on the south side, which offered shelter from the sun. The houses of Zubarah were constructed from soft local stone, or from limestone quarried from the northern settlement of Freiha.[74] The stone was then protected by a thick gypsum plaster coating. Features such as doorways and niches were decorated with geometric stucco designs. Housing units were accessible by a doorway and a bent corridor, in order to avert unauthorized viewing into the household, and to prevent sand from blowing into the house. Traces of what seems to be tent placements and/or palm-leaf and palm-matt huts found near the beach may be associated with transient members of the Zubaran society. It is likely that these interim dwellings housed the people who were the primary producers of Zubarah’s wealth: the pearl fishers and mariners who harvested the pearl banks each season.[75]

The most impressive and colossal of the building complexes measures 110 m by 100 m in size and is commonly referred to as 'the palace'.[38] This structure follows the same form as the domestic architecture seen elsewhere in Zubarah, but on a much larger scale. Nine interconnected compounds, each comprising a courtyard surrounded by a range of rooms, made up the interior of this structure. Plaster stucco decoration was used to embellish internal entrances and rooms. The discovery of internal staircases indicates that the compounds were multi-storeyed. The nine compounds of the complex were enclosed by a high circuit wall with circular towers at the four corners, each of which were capable of supporting a small cannon.[76] The size and visual dominance of the palatial compound suggests that it was occupied by a family of wealthy and powerful sheikhs who were community leaders in the social and economic life of the town.[77]

Fortifications

Protection of the town and its peoples' wealth was a clear priority.[37] A large wall was built in the late-18th-century town and its bay in a 2.5 km arc from shore to shore. The wall was defended by 22 semi-circular towers placed at regular intervals. It was faced by parapet with a walkway, most likely to provide leverage for gunners.[37] Access to the town was limited to a few defended gateways from the landside, or via its harbour. There was no sea wall, but a stout fort defended the main landing area on the sandy beach.[78]

In spite of its defensive fortifications, Zubarah was attacked on several occasions.[74] In addition to two major attacks carried out at the behest of Nasr Al-Madhkur in 1778, and 1782, the residents of the town were engaged in a war with the Banu Kaab of Khuzestan during the late eighteenth century.[79][80]

Industry

A large number of date-presses (madbassat) are found in houses throughout the town. They are small rooms with ridged plastered floors sloping to one corner where a jar would have been placed. Dates were packed in sacks and placed on the floor with weights on top to squeeze out the date juice - a sweet sticky syrup (dibs). The jar would collect and preserve the syrup for later consumption or use in cooking.[36] In 2014, a site was excavated which revealed the largest yet-discovered date-pressing site in the country and region. There were 27 date presses found overall, including 11 found in one lone complex.[81]

Attractions

Zubarah Fort

Zubarah is well known for the fortress of 1938, which was officially named after the town. The Zubarah Fort follows a traditional concept with a square ground plan with sloping walls and corner towers. Three of the towers are round while the fourth, the south east tower, is rectangular; each is topped with curved-pointed crenellations, with the fourth as the most machicolated tower. The fort’s design recalls earlier features common in Arab and Gulf fortification architecture, but varies by being constructed on concrete foundations. It marks the transition from solely stone-built structures to cement-based one, albeit in a traditional design.[82]

Originally, the fort was built as a base for the Qatari military and police to protect Qatar’s north-west coast as part of a series of forts along Qatar’s coastline. It was restored in 1987 with the removal of a number of much later auxiliary buildings erected to house the Qatari forces. After opening, the fort quickly became a major heritage attraction and, for a while, a local museum. Due to the unsuitable conditions in the fort for displaying and storing finds, the objects were relocated to Doha in 2010. Starting in 2011, the Qatar Museums Authority conducted a project of monitoring and restoration to ensure the upkeep of the fort. Between 2010 and 2013, parts of the fort were inaccessible to visitors.[82]

Qal'at Murair

The Murair Fort (Qal'at Murair in Arabic), situated 1.65 km (1.03 mi) east of the town of Zubarah, was built shortly after the town's settlement. The fort served to espouse Zubarah and especially entrenched the town’s primary fresh water source: groundwater reached by shallow wells. Within the fortification walls were a mosque, domestic buildings and at least one large well. Around the fort, several enclosures attest to the presence of fields, plantations or holding pens for animals, suggesting that this was also an agricultural settlement.[83]

A brief instance after the foundation of Zubarah, two screening walls were constructed from the outer town wall toward Qal'at Murair. These two walls, oriented east-west, include round towers placed at regular intervals, which strengthened their defensive capabilities.[73] The screening walls likely served to secure the transportation of water from the wells inside Qal'at Murair to Zubarah. In the harsh, hot summers of the Persian Gulf, water was a most valuable and beneficial commodity. The walls also channeled general traffic to and fro the town over open salt flats.[73]

Tourism

Zubarah was added to UNESCO’s World Heritage tentative list in 2008.[84] Since 2009, the site had been the subject of joint research by the QIAH and the Copenhagen, and development as a protected heritage site.[84] For protection, most of the site is enclosed within a fenced area. Additionally, visitors must pass a guard in order to enter the heritage town.

Prior to its addition to the World Heritage List, there was no visitor centre in the town. Other visitor facilities were sparse. In a parking lot next to the Zubarah fort, an information stand provided an overview and introduction to the site, fort and town. There were restrooms located near the fort, but there were no refreshments available in the vicinity.[85]

On June 22, 2013, UNESCO added the site to its World Heritage List. The UNESCO report stated that the town was distinguished its degree of preservation and its evidenced sustainment by pearl diving and commerce.[6] Following its inclusion in the list, the partially restored fort was transformed into a visitor centre and a number of rooms were designated for showcasing the subjects of pearling and astronomy.[62]

Guided tours of the town are offered, and field trips to the site are being integrated into various schools' history curriculum. There is also a self-guided tour, where the visitor is guided by signposts.[62] Tourism increased rapidly after the town's renovations were completed in 2014, attracting more than 30,000 visitors in the first three months of the year. This was a 170% increase from the entire 2013 season.[86]

Sports

The town currently hosts the Tour of Al Zubarah, a men's one-day cycle race which was rated as 2.2 by the UCI and forms part of the UCI Asia Tour.[87][88] It was selected as the host of the tournament in order to procure more media attention to the region, thereby amplifying tourism.[89] In addition, Zubarah is one of the host cities of the ladies' and men's Tour of Qatar and has been described as one of the toughest and longest stages in the course.[90]

A horse racing event known as Al Zubarah Cup is staged in the town.[91] A horse breeding farm, which is planned to be one of the largest in the region, is currently being constructed in the town. The project is funded by the Qatar Racing and Equestrian Club.[92]

Education

The following school is located in Zubarah:

| Name of School | Curriculum | Grade | Genders | Official Website | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Zubara Boys Schools | Independent | Primary – Secondary | Male-only | N/A | [93] |

Developments

The planned Qatar–Bahrain Friendship Bridge, slated to be the longest fixed link in the world, will connect the northwest coast of Qatar near Zubarah with Bahrain, specifically, south of Manama. Its location several kilometres south of Zubarah is planned so as to have negligible impact on the heritage site. It is expected to be constructed by 2022.[94]

An expansion of Zubarah road, a one-lane road leading to the archaeological site, was announced in 2014 by the Public Works Authority. It is planned to introduce three additional lanes.[95]

Archaeology and conservation

In March 1956, the site of Zubarah was included in the first Danish expeditions of Qatar and a team of archaeologists from Aarhus University and Moesgård Museum provided preliminary reconnaissance of the area. In 1962, Moesgård Museum archaeologist Hans Jørgen Madsen returned to ruins in Zubarah and conducted further survey.[96]

The Qatar Museums Authority (QMA) and its predecessor carried out two excavation projects in Zubarah, with the first during the early 1980s, and the latter in 2002-2003. The excavations in the 1980s were the more comprehensive of the two.[97]

In 2009, the QMA jointly launched the Qatar Islamic Archaeology and Heritage Project (QIAH) with the University of Copenhagen. The QIAH is a ten-year research, conservation and heritage initiative with the objective of investigating archaeological sites, preserving their fragile remains and working towards the presentation of the sites to the public. The project is an initiative by the Qatar Museums Authority’s chairperson H.E. Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani and vice-chairperson H.E. Hassan bin Mohamed bin Ali Al Thani.[8]

The QIAH project carried out a complete topographic survey of the site of Zubarah, the adjacent site of Murair, and the Zubarah Fort. Archaeological excavations have been undertaken at Zubarah and Qal`at Murair, supported by landscape studies in the hinterland. Numerous sites belonging to different chronological periods have been identified and recorded, and exploratory excavations have been conducted at a number of important localities, especially Freiha and Fuwayrit.[8]

A team from the University of Hamburg recorded the architectural remains of Zubarah in great detail with a 3D scanner. To preserve the architectural remains, a restoration program has been launched using special, saline resistant mortar and plasters to maximise the visitor experience, while abiding by UNESCO heritage guidelines. The aim of the conservation work is to preserve the authenticity of the site, as well as to preserve areas that can be enjoyed by visitors to the site through, among other means, interactive displays on mobile devices.[8]

Sovereignty disputes

.png)

There have been separate claims made by Qatar and Bahrain over the territory of Zubarah since the time of Ottoman occupation. Following the signing of the 1868 sovereignty treaty by the Al Thani, the earliest recorded disagreement over ownership occurred in 1873, when the Bahraini emir claimed sovereignty over Zubarah after he received false news of a military party that was supposedly en route to sack Zubarah.[47] In 1937, Hamad ibn Isa Al Khalifa of Bahrain alerted the local political resident to the long-running dispute. He, in turn, referred the issue to the political resident in Bushehr. The political resident in Bushehr wrote back, stating:

Personally I am of opinion that Zubara definitely belongs to Qatar but I am writing to His Majesty's Government, pending their decision you should avoid giving any opinion at all to Bahrain Government on the matter including the fact that I am referring the question.[98]

Hamad ibn Isa wrote again to the political resident in Bahrain in 1939 to inform him that Abdullah Al Thani was constructing a fort in Zubarah. He contended that the construction was illegal because he held sovereignty over the land.[99] A settlement was reached in 1944 during a meeting mediated by the Saudis, in which Qatar recognized Bahrain's customary rights, such as grazing, and visiting with no formalities necessary. However, Abdullah broke the accord when he constructed a fort in the town. The strenuous relationship between the two countries improved in 1950 after Ali Al Thani ascended to the throne.[100]

In 1953, Bahrain again reiterated its claims over Zubarah when it sent a party of students and teachers to Zubarah who proceeded to write 'Bahrain' on the walls of Zubarah Fort. Furthermore, the Bahrain Education Department published maps which alleged Bahraini sovereignty over the entire northwest coast of the peninsula. Ali responded by occupying the fort in 1954 and later added police in 1956.[100]

Following the independence of Qatar in 1971 from the British Empire, Bahrain continued to dispute Qatari sovereignty over Zubarah until the case was settled in Qatar's favour with a ruling by the International Court of Justice in 2001.[101]

The issue of sovereignty came up again following the onset of the Qatar diplomatic crisis. In June 2018, the Bahrain Center for Strategic, International and Energy Studies (DERASAT) held a conference on the history of the Al Khalifa family's control of Qatar until 1868, during which they urged the Bahraini government to renew its claims over Zubarah.[102] In August, the King of Bahrain Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa publicly met with the Naim tribe, natives of Zubarah who in the past professed allegiance to the King of Bahrain, and said in a statement that "we will not forget the illegal aggression against Zubarah", referring to Sheikh Abdullah Al Thani's excursion against the Naim tribe in 1937.[103]

In popular culture

An independent and modernized Zubarah (spelled Zubara) is the setting for much of Larry Correia's and Micheal Kupari's military thriller Dead Six.[104]

See also

References

- تاريخ نجد – خالد الفرج الدوسري – ص 239

- Rihani, Ameen Fares (1930), Around the coasts of Arabia, Houghton Mifflin Company, page 297

- Arabian Frontiers: The Story of Britain’s Boundary Drawing in the Desert, John C Wilkinson, p44

- قلائد النحرين في تاريخ البحرين تأليف ناصر بن جوهر بن مبارك الخيري، تقديم ودراسة عبدالرحمن بن عبدالله الشقير،2003، ص 215.

- المصالح البريطانية في الكويت حتى عام 1939، أحمد حسن جودة، ترجمة حسن النجار، مطبعة الارشاد، بغداد، 1979، ص 35

- "Al Zubarah Archaeological Site". UNESCO. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Richter, T., Wordsworth, P. D. & Walmsley, A. G. 2011: Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah. P. 2. In Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, p. 1-16

- "Qatar Islamic Archaeology and Heritage Project". University of Copenhagen. 2010-10-11. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "The Pearl Emporium of Al Zubarah". Saudi Aramco World. December 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Rahman, Habibur (2006). The Emergence Of Qatar. Routledge. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0710312136.

- Rahman, p. 47

- Reisman, W. Michael (2014). Fraudulent Evidence before Public International Tribunals: The Dirty Stories of International Law (Hersch Lauterpacht Memorial Lectures). Cambridge University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-1107063396.

- "Court memorial submitted by Bahrain" (PDF). International Court of Justice. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- تاريخ آل خليفة في البحرين - الشيخ عبدالله بن خالد آل خليفة والدكتور علي أبا حسين، الجزء الثاني، ص 18

- Al Khalifa, A.b.K. & Hussain A.A. 1993. The Utoob in the eighteenth century. Pages 301–334 in A.b.K. Al Khalifa & M. Rice (eds), Bahrain through the ages: the history. London: Kegan Paul.

- Abu Hakima A.M. 1965. History of Eastern Arabia 1750–1800. The Rise and Development of Bahrain and Kuwait. Beirut: Khayats.

- Lorimer J.G. 1915. Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman and Central Arabia. i. Historical. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent Government Printing

- Wilkinson, John Craven (1991). Arabia's frontiers: the story of Britain's boundary drawing in the desert. I.B. Tauris. p. 44.

- Rihani, Ameen Fares (1930). Around the coasts of Arabia. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 297.

- Arabian Studies By R.B. Serjeant, R.L. Bidwell, p67

- Rahman, p. 50

- Rahman, p. 51

- "World Heritage" (PDF). Vol. 72. UNESCO. June 2014. p. 36. Retrieved 5 July 2018. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - Richter, T., Wordsworth, P. D. & Walmsley, A. G. 2011: Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah. P. 4. In Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, p. 1-16

- Khuri 1980, p. 24.

- Al-Qāsimī, Sulṭān ibn Muḥammad (1999). Power Struggles and Trade in the Gulf: 1620-1820. Forest Row. p. 168.

- Shaikh Hamad Bin Isa Al-Khalifa, First Light: Modern Bahrain and its Heritage, 1994 p41

- the Precis Of Turkish Expansion On The Arab Littoral Of The Persian Gulf And Hasa And Katif Affairs. By J. A. Saldana; 1904, I.o. R R/15/1/724

- Rahman, p. 52

- Al-Dabbagh, M. M. (1961). Qatar, its past and its present. p. 11.

- Abdulla Juma Kobaisi. "The Development of Education in Qatar, 1950–1970" (PDF). Durham University. p. 31. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- Vine, P. & Casey, P. 1992: The Heritage of Qatar. P. 29. IMMEL Publishing

- Rahman, p. 53

- "Arabia, Yemen, and Iraq 1700-1950". san.beck.org. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Rahman, p. 54

- Richter, T., Wordsworth, P. D. & Walmsley, A. G. 2011: Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah. P. 6-7 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, p. 1-16

- "World Heritage No. 72" (PDF). World Heritage Committee. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Gillespie, Frances; Al-Naimi, Faisal Abdulla (2013). Hidden in the Sands - Uncovering Qatar's Past. Medina Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 978-1909339064.

- Richter, T., Wordsworth, P. D. & Walmsley, A. G. 2011: Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah. P. 5 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, p. 1-16

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [843] (998/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- James Onley 2004: “The Politics of Protection in the Gulf: The Arab Rulers and the British Resident in the Nineteenth Century” (2004). P.31 in New Arabian Studies (Exeter University Press, 2004), Vol. 6, pp. 30–92

- Rahman, p. 35–37

- "The Pearl Emporium of Al Zubarah". saudiaramcoworld.com. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Richter, T., Wordsworth, P. D. & Walmsley, A. G. 2011: Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah. P. 5-6 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, p. 1-16

- Fromherz, Allen James (2012). Qatar: A Modern History. Georgetown University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-1589019102.

- "'Persian Gulf Gazetteer, Part I Historical and Political Materials, Précis of Bahrein Affairs, 1854-1904' [35] (54/204)". qdl.qa. 2014-04-04. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- "'Persian Gulf Gazetteer, Part I Historical and Political Materials, Précis of Bahrein Affairs, 1854-1904' [36] (55/204)". qdl.qa. 2014-04-04. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- Rahman, p. 141–142

- Rahman, p. 142–143

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [817] (972/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [818] (973/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- Bidwell, Robin (1998). Dictionary Of Modern Arab History. Kegan Paul. p. 455. ISBN 978-0710305053.

- "'Persian Gulf gazetteer. Part 1. Historical and political materials. Précis of Katar [Qatar] affairs, 1873-1904.' [26v] (52/92)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "'Persian Gulf gazetteer. Part 1. Historical and political materials. Précis of Katar [Qatar] affairs, 1873-1904.' [27r] (53/92)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Persian Gulf gazetteer. Part 1. Historical and political materials. Précis of Katar [Qatar] affairs, 1873-1904.' [27v] (54/92)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol. II. Geographical and Statistical. J G Lorimer. 1908' [1952] (2081/2084)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 February 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Peck, Malcolm C. (2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gulf Arab States. Scarecrow Press. p. 324. ISBN 978-0810854635.

- "'File 4/13 II Zubarah' [8r] (20/543)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- "'File 4/13 II Zubarah' [12r] (28/543)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- "Al Zubara Fort". The Peninsula Qatar. 19 July 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- Belgrave, C. 1960. Personal Column. London: Hutchinson, Ch. 15.

- Rosendahl, Sandra. "Al Zubarah Archaeological Site and the Qatar Islamic Archaeology and Heritage Project: Outreach and Presentation Strategies in an Open-Air Museum". academia.edu. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Amor, Kirsten (2 June 2011). "Exploring the Ancient Ruins of Qatar's Zubarah City". vagabondish.com. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "QULTURA MAGAZINE issue 1". issuu.com. Qultura Magazine. p. 64. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "Qatar islamic archaeology and heritage project" (PDF). University of Copenhagen and Qatar Museums Authority. 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "Al Zubarah Fort Qatar". New in Doha. 21 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Vine, P. & Casey, P. 1992: The Heritage of Qatar. P. 49-55. IMMEL Publishing

- Bowen R. Le B. 1951: The Pearl Fisheries of the Persian Gulf. In The Middle East Journal 5/2: 161–180.

- Walmsley, A.; Barnes, H. & Macumber, P. 2010: Al-Zubarah and its hinterland, north Qatar: excavations and survey, spring 2009. P. 65 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 40, p.55-68

- "Danske arkæologer udgraver skattely fra 1700-tallet". Videnskab.dk. 12 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Richter, T., Wordsworth, P. D. & Walmsley, A. G. 2011: Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah. P. 9 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, p. 1-16

- Walmsley, A.; Barnes, H. & Macumber, P. 2010: Al-Zubarah and its hinterland, north Qatar: excavations and survey, spring 2009. P. 63-65 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 40, p.55-68

- Rees, G., Walmsley, A. G. & Richter, T. 2011: Investigations in the Zubarah Hinterland at Murayr and Furayhah, North-West Qatar. P. 310 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, 309-316

- Gillespie, Frances; Al-Naimi, Faisal Abdulla (2013). Hidden in the Sands - Uncovering Qatar's Past (print ed.). Medina Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 978-1909339064.

- Richter, T., Wordsworth, P. D. & Walmsley, A. G. 2011: Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah. P. 12 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, p. 1-16

- Richter, T., Wordsworth, P. D. & Walmsley, A. G. 2011: Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah. P. 9-11 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, p. 1-16

- Richter, T., Wordsworth, P. D. & Walmsley, A. G. 2011: Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah. P. 11 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, p. 1-16

- Walmsley, A.; Barnes, H. & Macumber, P. 2010: Al-Zubarah and its hinterland, north Qatar: excavations and survey, spring 2009. P. 59-60 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 40, p.55-68

- Nyrop, Richard F. (2008). Area Handbook for the Persian Gulf States. Wildside Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-1434462107.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [1003] (1158/1782)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "Qatar Museums announces a new discovery at Al Zubarah". The Peninsula Qatar. 9 July 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "Al Zubarah Fort (archived version)". qma.org.qa. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Richter, T., Wordsworth, P. D. & Walmsley, A. G. 2011: Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah. P. 13 in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41, p. 1-16

- "Homing in on Heritage". behereonline.com. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Al-Kholaifi M.J. 1987: Athar. Al-Zubarah and Marwab. Doha: Ministry of Information, Department of Tourism and Antiquities. (in arabic)

- "Record visitor numbers at Al Zubarah". qatarisbooming.com. 29 May 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "2nd Tour of Al Zubarah (2.2)". procyclingstats.com. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "2015 Asia Tour". procyclingstats.com. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "Inaugural Tour of Zubarah from December 4". Gulf Times. 29 November 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "Lucy Garner's Ladies Tour of Qatar blog: stage two". cyclingweekly.co.uk. 4 February 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "O'Shea shines as Mekhbatt tops Al Zubarah Cup field". The Peninsula Qatar. 23 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- "Arabian Farm Tours". The 2014 WAHO Conference. p. 5. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "Qatari Schools". Supreme Education Council. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- "Qatar-Bahrain causeway faces delay, says minister". thepeninsulaqatar.com. 23 December 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Zubarah road expansion". Gulf Times. 15 February 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Kapel, Holger (1967). Atlas of the Stone-Age cultures of Qatar. Aarhue University Press. pp. 5–12.

- Al-Kholaifi M.J. 1987: Athar. Al-Zubarah and Marwab. Doha: Ministry of Information, Department of Tourism and Antiquities. (in Arabic)

- "'File 19/243 I (C 69) Zubarah' [3r] (16/416)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "'File 19/243 III (C 95) Zubarah' [78r] (166/462)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Crystal, Jill (1995). Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar. Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0521466356.

- "Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions between Qatar and Bahrain (Qatar v. Bahrain)". International Court of Justice. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- Mustafa Al Zarooni (1 July 2018). "Conference urges Bahrain to stake claim for lands under Qatar control". Khaleej Times. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- "Bahraini King's Comments on Qatar Provokes Controversy". Tasnim News. 19 August 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- Larry., Correia (2011-09-27). Dead Six. Kupari, Mike. New York. ISBN 9781451637588. OCLC 701811253.

Further reading

- Abu Hakima, A.M. (1965). History of Eastern Arabia 1750–1800. The Rise and Development of Bahrain and Kuwait. Khayats.

- Abu-Lughod, J.L. (1987). "The Islamic City — Historic Myth, Islamic Essence, and Contemporary Relevance". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 19/2 (2): 155–176. doi:10.1017/S0020743800031822.

- Al Khalifa, A.b.K.; Hussain, A.A. (1993). "The Utoob in the eighteenth century". In Al Khalifa, A.b.K.; Rice, M. (eds.). Bahrain through the ages: the history. London: Kegan Paul. pp. 301–334.

- Bibby, G. (1969). Looking for Dilmun. New York: Knopf.

- Bille, M., ed. (2009). End of the Season Report 2009, Vol. 1. Archaeological Excavations & Survey at az-Zubarah, Qatar. University of Copenhagen/Qatar Museums Authority.

- Bowen, R. Le B. (1951). "The Pearl Fisheries of the Persian Gulf". The Middle East Journal. 5/2: 161–180.

- Breeze, P.; Cuttler, R.; Collins, P. (2011). "Archaeological landscape characterization in Qatar through satellite and aerial photographic analysis, 2009 to 2010". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41.

- Brucks, G.B. (1865). "Navigation of the Gulf of Persia". In Thomas, R.H. (ed.). Arabian Gulf Intelligence. Selections from the Records of the Bombay Government. Concerning Arabia, Kuwait, Muscat and Oman, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and the Islands of the Gulf. Cambridge: The Oleander Press. pp. 531–580.

- Carter, R. (2005). "The History and Prehistory of Pearling in the Persian Gulf". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. Brill. 48 (2): 139–209. doi:10.1163/1568520054127149. JSTOR 25165089.

- Fuccaro, N. (2009). "Histories of City and State in the Persian Gulf: Manama since 1800". Cambridge Middle East Studies. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press. 30.

- Grey, Anthony (2011). "Late Trade Wares on Arabian Shores: 18thc to 20th century imported fine ware ceramics from excavated sites on the southern Persian Gulf coast". Post-medieval Archaeology. 45/2: 350–373.

- Lorimer, J.G. (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman and Central Arabia. i. Historical. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent Government Printing.

- Moulden, H.; Cuttler, R.; Kelleher, S. (2011). "Conserving and Contextualising National Cultural Heritage: The 3D digitisation of the Fort at Al Zubarah and Petroglyphs at Jebel Jassasiya, Qatar". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41.

- Onley, James (2004). "The Politics of Protection in the Gulf: The Arab Rulers and the British Resident in the Nineteenth Century". New Arabian Studies. Exeter University Press. 6: 30–92.

- Rahman, H. (2005). The Emergence of Qatar: the turbulent years 1627–1916. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Rees, G.; Walmsley, A. G.; Richter, T. (2011). "Investigations in the Zubarah Hinterland at Murayr and Furayhah, North-West Qatar". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41: 309–316.

- Richter, T., ed. (2010). Qatar Islamic Archaeology and Heritage Project. End of Season Report. Stage 2, Season 1, 2009-2010. University of Copenhagen/Qatar Museums Authority.

- Richter, T.; Wordsworth, P. D.; Walmsley, A. G. (2011). "Pearlfishers, townsfolk, Bedouin and Shaykhs: economic and social relations in Islamic Al-Zubarah". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41: 1–16.

- Walmsley, A.; Barnes, H.; Macumber, P. (2010). "Al-Zubarah and its hinterland, north Qatar: excavations and survey, spring 2009". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 40: 55–68.

- Warden, F. (1865). "Uttoobee Arabs (Bahrein)". In Thomas, R.H. (ed.). Arabian Gulf Intelligence. Selections from the Records of the Bombay Government. Concerning Arabia, Kuwait, Muscat and Oman, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and the Islands of the Gulf. Cambridge: The Oleander Press. pp. 362–425.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zubarah. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Zubarah. |

- Official website of Al Zubarah Archaeological Site

- Photos of Zubarah Fort

- Excavations at Zubara

- University of Copenhagen, Qatar Islamic Archaeology and Heritage Project

- UNESCO's tentative list

- Al-Zubarah Pearl of the Past. A documentary from 2011

- 360 degrees panoramic virtual tour of the Al Zubarah fort

- Culture and Heritage under Qatar Museums Authority: Al Zubarah fort

- James, Bonnie (March 24, 2012), "Zubarah's heritage list hopes get a lift", Gulf Times, retrieved March 30, 2012

- "Students gain insight into Al Zubarah's historic role", Gulf Times, February 25, 2012, retrieved March 30, 2012

- James, Bonnie (January 21, 2012), "New tools to unearth Zubarah secrets", Gulf Times, retrieved March 30, 2012

- "Hi-tech survey at Al Zubarah site", Gulf Times, January 21, 2012, retrieved March 30, 2012

- "Excavation at historic site uncovers date presses used to produce syrup", Gulf Times, February 25, 2011, retrieved March 30, 2012

- James, Bonnie (February 11, 2011), "Remains of palatial compound", Gulf Times, retrieved March 30, 2012

- Mogensen, Anna (March 12, 2010), "Danish-led Excavation in Qatar", FOCUS Denmark, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, retrieved March 30, 2012

- Walmsley, Alan (December 8, 2011). "The legacy of Zubarah". Qultura Magazine. Vega Media and Katara. 1: 58–65. Retrieved March 30, 2012.