AkzoNobel

Akzo Nobel N.V., trading as AkzoNobel, is a Dutch multinational company which creates paints and performance coatings for both industry and consumers worldwide. Headquartered in Amsterdam, the company has activities in more than 80 countries, and employs approximately 46,000 people. Sales in 2016 were EUR 14.2 billion.[2]

.jpg) AkzoNobel's headquarters in Amsterdam | |

| Naamloze Vennootschap | |

| Traded as | Euronext Amsterdam: AKZA |

| ISIN | NL0013267909 |

| Industry | Chemicals |

| Founded | 1994 |

| Headquarters | Amsterdam, Netherlands |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Thierry Vanlancker (CEO) Nils Smedegaard Andersen (Chairman of the supervisory board) |

| Products | Basic and industrial chemicals, decorative paints, industrial (re)finishing products, coatings |

| Revenue | €9.61 billion (2018)[1] |

| €5.157 million (2018)[1] | |

| €6.674 million (2018)[1] | |

| Total assets | €19.128 million (end 2018)[1] |

| Total equity | €11.834 million (end 2018)[1] |

Number of employees | 34,500 (end 2018)[1] |

| Website | www |

History

AkzoNobel has a long history of mergers and divestments. Parts of the current company can be traced back to 17th-century companies.[3] The milestone mergers and divestments are the formation of AKZO in 1969, the merger with Nobel Industries in 1994 forming Akzo Nobel, and the divestment of its pharmaceutical business and the merger with ICI in 2007/2008 resulting in current-day AkzoNobel.

History and formation of Akzo

In 1887 Zwanenberg's Fabrieken, a meat export factory based in Oss, Netherlands, was established. In 1923, Organon, pharmaceuticals company was founded by Saal van Zwanenberg in Oss, by 1947 both companies had merged to form Zwanenberg–Organon, which in 1953, with Royal consent, was renamed to Koninklijke Zwanenberg-Organon (KZO). In 1965, the company acquired the chemical company, Kortman and Schulte (Est. 1886) and Noury & Van der Lande (Est. 1838). In 1967 KZO merged with Koninklijke Zout Ketjen—itself the result of a merger of Ketjen (Est. 1835) and Koninklijke Nederlandse Zoutindustrie (KNZ) (Est. 1918)—and acquired Sikkens Lakken (Est.1792), forming Koninklijke Zout Organon.

In 1929 Vereinigte Glanzstoff Fabrike (Est. 1899) and Nederlandse Kunstzijdefabriek (Est. 1911) merged, forming Algemene Kunstzijde Unie (AKU). The latter, known as the ENKA, is universally acknowledged as the parent of AkzoNobel, which faced along with others technical problems in the manufacturing of synthetic fibers. Jacques Coenraad Hartogs, the founder of the Nederlandse Kunstzijdefabriek (ENKA), turned to Dutch industrialist and friend, Rento Hofstede Crull for a solution for which Hofstede Crull provided the answer. They created a joint venture, the NV I.S.E.M. whose success and profits laid the foundation for the ENKA's subsequent acquisitions and mergers, resulting in the AkzoNobel of today. NV I.S.E.M. was absorbed by the AKU in 1938 with Hofstede Crull's death.[4]

In 1969 Algemene Kunstzijde Unie and Koninklijke Zout Organon merged, forming Akzo. In the following years the company made a number of critical acquisitions; Armour and Company in 1970,[5] Levis Paints in 1985, specialty chemicals division of Stauffer in 1987 and divested its polyamides and polyesters plastics engineering business to DSM in 1992. In 1993, Akzo formed a joint venture with Harrisons Chemicals (UK) Ltd a subsidiary of Harrisons & Crosfield.

History and formation of Nobel

In 1646, the Swedish weapons manufacturer Bofors was established in Karlskoga. In 1893 the company became majority owned by Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel. In 1984 Bofors acquired KemaNobel, which had been established in 1841 and then existed as the result of mergers and acquisitions in 1970: Liljeholmens Stearinfabriks chemicals business (established 1841), Barnängen Tekniska Fabrik AB (1868) and Casco (1928).

In the late 70s and early 80s the company continued to make a number of acquisitions. In 1978 KemaNord acquired Swedish civil explosives chemical group Nitro Nobel and Liljeholmens Stearinfabrik; in 1981 it acquired Swedish electronics group Pharos from AGA and a year later the paints group Nordsjö. In 1983 the group consolidated the food systems groups of KenoGard and Kema Nobel to form Probel, later called Nobel Biotech. In 1984 Bofors acquired majority interest in KemaNobel, both companies have historic ties to Alfred Nobel, the 19th century Swedish inventor whose invention of dynamite gave a safe way to manage the detonation of nitroglycerin. By 1985 Bofors had integrated the entire KemaNobel group into itself and changed its name to Nobel Industries.

In 1986 the group divested its civil explosives business, Nitro Nobel, whilst acquiring paper and pulp group Eka AB. In 1988 the company acquired Berol Kemi from Procordia.

In 1986 the company acquired Elektrokemiska Aktiebolaget (Eka), another company founded by Alfred Nobel in 1895. Eka acquired Swedish forest company Iggesunds Bruk AB in 1951. In the late 80s a number subsidiary companies made various acquisitions; Casco Nobel acquired: Sadolin & Holmblad in 1987, Parteks adhesives and joint compound operations in 1988 and English paints group, Crown Berger in 1990. In 1990, Pharos acquired American electronics group Spectra-Physics. By the mid 90s, the company had begun to divest itself of non core businesses, streamlining itself: KVK Agro Chemicals was sold to Sandoz in 1991, the Nobel Consumer Goods (which consisted of: Barnängen Tekniska Fabrik, Liljeholms, Sterisol, and Vademecum, in the main) to the German group, Henkel, and NobelTech (the consolidated electronic business operation of the group) to Celsius Industries.

AkzoNobel formation

In 1994 Akzo and Nobel Industries agreed to merge, forming Akzo Nobel, with the new combined entity having 20 business entities a number of divestments were made: Nobel Chemicals, Nobel Biotech and Spectra-Physics. In 1995 the PET resins business was sold to Wellman, Inc.. In 1996 the group sold the crop protection business to Nufarm. In 1998 the company acquired industrial coatings and in synthetic fiber company Courtaulds, later divesting Courtaulds industrial coatings and Daejen Fine Chemicals. Courtaulds was merged with Akzo Nobel Fibres forming Acordis, which in December 1999 was divested CVC Capital Partners. In 1999 the company acquired the pharmaceutical business of Kanebo, the Italian pharmaceutical manufacturer, Farmaceutici Gellini, Nuova ICC and Hoechst Roussel Vet.

In the early 2000s the company began another wave of divestitures, first in 2000 with its stake in Rovin's VCM and PVC business to Shin-Etsu Chemical. In 2001 divests ADC optical monomers business to Great Lakes Chemical, in 2002 its printing inks business, in 2004 its catalyst business to Albemarle Corp., in 2005 its Ink & Adhesive Resins to Hexion and UV/EB Resins to Cray Valley, in 2007 its Akcros Chemicals to GIL Investments. In 2006 the group acquired Canadian decorative and industrial coatings company, SICO Inc. and a year later Canadian industrial coatings company, Chemcraft International, Inc.

In 2007 Organon International was sold to Schering-Plough for €11 billion and AkzoNobel delisted its shares from the US NASDAQ stock market. In 2008 Crown Paints was sold in a management buyout.[6]

In December 2012, AkzoNobel agrees to sell its North American Architectural Coatings business to PPG Industries for $1.1 billion[7]

Acquisition of Imperial Chemicals Industries (ICI)

In 2008 AkzoNobel acquired British Imperial Chemical Industries plc for $15.8 billion.[8]

ICI can trace its history back to four British-based chemical companies; British Dyestuffs Corporation, Brunner, Mond & Company, Nobel Explosives, and the United Alkali Company.[9] which merged in 1926, forming ICI. A year later, the newly merged entity employed over 33,000 employees in five main product areas: alkali products, explosives, metals, general chemicals, and dyestuffs. In 1933 the company "discovered" polyethylene, which is later patented and sold as an insulating material. In 1986 focusses to paint and specialty products with the purchase of Beatrice's Chemicals Division and Glidden Paint.

In 1993 ICI demerged its bioscience business, splitting into two the publicly listed companies: ICI and Zeneca—Zeneca would later go onto merge with Astra AB, forming the current pharmaceutical company, AstraZeneca. In 1997 ICI acquired four businesses from Unilever: National Starch, Quest, Uniqema, and Crosfield and began to divest its bulk commodity businesses. In 1999 five ICI businesses, were merged forming the health and personal care products company, Uniqema as well as selling polyurethanes, the titanium dioxide, the aromatics businesses and its share of the olefins supply at Wilton to Huntsman. In 2007, Uniquema was sold to Croda International.

In June 2010, AkzoNobel divested its National Starch business to Corn Products International.

Attempted acquisition by PPG Industries

In March 2017, PPG Industries launched an unsolicited takeover bid of €20.9bn, which was promptly rejected by AkzoNobel's management.[10] Days later, PPG again launched an increased bid of €24.5 billion ($26.3 billion), which was again rejected by AkzoNobel's management.[11] A number of shareholders urged the company to explore the offer and subsequent negotiations.[12][13] In April, activist investor, Elliot Investors' called for the removal of Chairman Antony Burgmans following Akzo's refusal to submit to discussing with PPG. Elliott, which has a 3.25% stake in the company, claimed it was one of a group of investors that met the Dutch legal threshold of 10% voting-share support, which is needed to call an extraordinary meeting to vote on a proposal to remove Burgmans.[14] On April 13, Templeton Global Equity said it was among another group of investors calling for an extraordinary meeting of AkzoNobel shareholders to discuss Burgmans continued tenure as Chairman.[15] Later, in the same month Akzo outlined its plan to separate its chemicals division and pay shareholders €1.6 billion in extra dividends, in order to attempt to hold-off PPG.[16][17] The new Akzo strategy was dismissed by PPG, which claimed that their offer represented better value for shareholders,[18][19] supported by activist Akzo shareholder, Elliot Advisors.[20] On April 24, a day before Akzo's annual meeting of shareholders, PPG increased its final offer by approximately 8% to $28.8 billion (€26.9 billion, €96.75 per share)—with Akzo's share pricing rising 6% to a record price of €82.95 per share.[21] Akzo shareholder, Columbia Threadneedle Investments, urged the company to open dialogue with PPG,[22] whilst PPG claimed that the deal would add to earning within its first year.[23] Days later one of Great Britain's largest pension scheme investors, Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS), urged Akzo to engage with PPG.[24] On 2 May, Reuters revealed that the supervisory board of Azko was meeting to discuss how to deal with PPGs third offer, still maintaining it did not value the company highly enough.[25]

In early May, Akzo again rejected PPGs bid, citing the deal still undervalued the company, as well as potentially facing antitrust risks, and not addressing other concerns such as "cultural differences". Under Dutch company law, PPG had to then decide to either make a formal bid or walkaway.[26] In early June, PPG chose to walk away from the potential deal.[27][28] As part of Akzo's defense to shareholders, many of whom pushed for the deal, chief executive Ton Büchner agreed to split Akzo in two and achieve increased financial targets.[29] Büchner stepped down as CEO in July 2017, citing health reasons. He was succeeded by Thierry Vanlancker, former chief of the company's chemicals division.[30]

Recent

The company AkzoNobel is focused on paints and coatings. On October 9, 2018 Specialty Chemicals was re-branded as a new company, Nouryon, after acquisition by the Carlyle Group.[31]

Organization

AkzoNobel consists of three main business areas, as well as corporate functions, with business responsibility and autonomy.

Currently, a seven-member-strong Executive Committee (ExCo) was established, which is composed of two members of the Board of Management (BoM) and five leaders with functional expertise, allowing both the functions and the business areas to be represented at the highest levels in the company.

The ExCo includes Chairman and CEO Thierry Vanlancker, CFO Maarten de Vries, Marten Booisma (responsible for Human Resources), Isabelle Deschamps (General Counsel), Werner Fuhrmann (responsible for Specialty Chemicals), Ruud Joosten (Chief Operating Officer, Paints & Coatings). The board holds office in Amsterdam. Prior to August 2007, the Executive Committee was headquartered in Arnhem.

Due to high revenues from the sales of its pharmaceutical business, AkzoNobel was the world's most profitable company in 2008.[32]

Decorative paints

This part of the business is mostly geographically organised:

- Europe, Middle East and Africa

- Latin America

- Asia

AkzoNobel markets their products under various brandnames such as Dulux, Bruguer, Tintas Coral, Hammerite, Herbol, Sico, Sikkens, International, Interpon, Casco, Nordsjö, Sadolin, Cuprinol, Taubmans, Lesonal, Levis, Glidden, Flood, Flora, Vivexrom, Marshall, and Pinotex among others. These products were used on London's Millennium Wheel, La Scala Opera House in Milan, the Öresund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden, the Beijing National Stadium, Airbus A380, and Stadium Australia in Sydney.

Performance coatings

AkzoNobel is a leading coatings company whose key products include automotive coatings, specialised equipment for the car repair and transportation market and marine coatings. The coatings groups consist of the following business units:[33]

- Marine Coatings

- Protective Coatings

- Vehicle Refinishes

- Specialty Coatings

- Metal Coatings

- Wood Coatings

- Powder Coatings

Specialty chemicals

The speciality chemicals group was sold in 2018 and is now named Nouryon.

It consisted of four business units.[33]

- Functional Chemicals (FC)

- Industrial Chemicals (IC), before 1 January 2009 known as Base Chemicals (BC)

- Pulp and Performance Chemicals, under brand name Eka (PPC)

- Surface Chemistry (SC)

The divestment of the former business unit of Chemicals Pakistan was completed in Q4 2012.

As chemicals producer, AkzoNobel was a world leading salt specialist, chloralkali products, and other industrial chemicals. Ultimately, AkzoNobel products were found in everyday items such as paper, ice cream, bakery goods, cosmetics, plastics and glass. Each business unit had an annual turnover of approximately EUR 1 billion to 1.9 billion.[34]

Expancel

Expancel is a unit within AkzoNobel.[35][36][37][38] Expancel produces expandable microspheres under the tradename "Expancel Microspheres". Expancel has its head office in Sundsvall, Sweden. Production, R&D, sales and marketing is located in Sundsvall. Expancel has sales offices in Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Russia, Italy, US, Brazil, Thailand, Singapore and China. The number of employees is about 200.

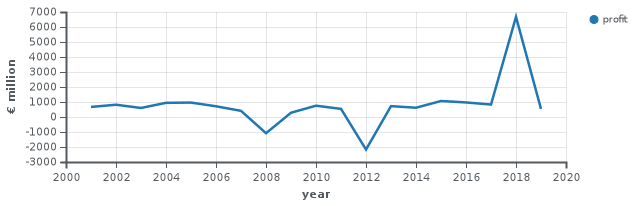

Turn-over and profit history

| Year | Turn-over | Profit |

|---|---|---|

| 2017[39] | ||

| 2016[2] | ||

| 2015[33] | ||

| 2014[34] | ||

| 2013 | ||

| 2012 | ||

| 2011 | ||

| 2010[40] | ||

| 2009[40] | ||

| 2008 | ||

| 2007 | ||

| 2006 | ||

| 2005 | ||

| 2004 | ||

| 2003 | ||

| 2002 | ||

| 2001 |

See also

- Herbol, an industrial coating brand by AkzoNobel

- Twaron, trade name of aramid synthetic fiber

- Teijin Aramid, producer of Twaron, former AkzoNobel company

- GLARE, composite material patented by AkzoNobel

- List of companies in the Netherlands

- List of companies of Sweden

References

- "AkzoNobel Report 2018" (PDF).

- "AkzoNobel Report 2016". AkzoNobel. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Tomorrow's answers today, AkzoNobel 2008 Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-90-902288-3-9, English version

- History of the NV I.S.E.M.: ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)); Jaap Tuik. Een bijzonder energiek ondernemer - Rento Wolter Hendrik Hofstede Crull (1863-1938): pioneer van de elektriciteits voorziening in Nederland Zutphen, Netherlands: Historisch Centrum Overijsssel & Walberg Pers, 2009. pp: 137- 138 ISBN 978-90-5730-640-2

- AkzoNobel company history Archived 20 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, fundinguniverse.com

- Tyler, By Richard (3 August 2008). "Akzo Nobel give up Crown Paints". Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- Kreijger, Sara Webb and Gilbert. "AkzoNobel sells North American paint arm to PPG for $1.1 billion". Archived from the original on 27 March 2017.

- "BBC NEWS - Business - Akzo Nobel ICI merger completed". Archived from the original on 20 May 2009.

- "ICI: History". ICI. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008.

- "Subscribe to read". Archived from the original on 26 March 2017.

- "PPG Makes Revised Proposal to Combine with AkzoNobel". Archived from the original on 28 March 2017.

- "AkzoNobel shareholders turn up the heat on Dulux owner over rejected PPG takeover bid". Archived from the original on 15 February 2018.

- Whitfield, Graeme (24 March 2017). "Largest shareholder at big North East employer AkzoNobel urges takeover talks". Archived from the original on 27 March 2017.

- Sherman, Natalie (12 April 2017). "Akzo Nobel faces call to axe chairman amid takeover battle". Archived from the original on 13 April 2017 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- Editorial, Reuters. "Another Akzo Nobel investor calls for meeting on chairman". Archived from the original on 16 April 2017.

- Sterlink, Toby (18 April 2017). "Akzo Nobel unveils plan to separate chemicals arm, pay special dividend". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- Editorial, Reuters. "Akzo Nobel beats on first quarter operating profit, sees 2017 growth". Archived from the original on 19 April 2017.

- Editorial, Reuters. "PPG Industries says Akzo Nobel's new plan is worse for shareholders". Archived from the original on 20 April 2017.

- Keidan, Toby Sterling and Maiya. "PPG dismisses Akzo Nobel defence, presses takeover case". Archived from the original on 19 April 2017.

- Editorial, Reuters. "Elliott calls Akzo Nobel strategic plan 'incomplete'". Archived from the original on 20 April 2017.

- Sterling, Toby. "PPG raises offer for Akzo Nobel to $29 billion". Archived from the original on 24 April 2017.

- Editorial, Reuters. "Akzo Nobel shareholder Columbia Threadneedle urges talks with PPG". Archived from the original on 25 April 2017.

- Editorial, Reuters. "Akzo Nobel purchase would add to earnings in first year - PPG CEO". Archived from the original on 25 April 2017.

- Editorial, Reuters. "Akzo Nobel investor USS backs call for PPG talks over revised bid". Archived from the original on 29 April 2017.

- Roumeliotis, Greg. "Exclusive - Akzo sees latest PPG bid inadequate, weighs options-sources". Archived from the original on 3 May 2017.

- Sterling, Toby. "Akzo Nobel declines third takeover proposal from PPG". Archived from the original on 8 May 2017.

- Barbaglia, Pamela. "How PPG lost its $29.5 billion bet on Dulux paint". reuters.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Sterling, Toby. "Akzo responds to PPG approach after takeover battle ends". reuters.com. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Pooler, Michael (4 June 2017). "Akzo faces tough battle after fending off PPG". Financial Times. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- Sterling, Toby (19 July 2017). "Akzo Nobel CEO quits, successor must deliver merger defense promises". Reuters. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Nouryon (9 October 2018). "AkzoNobel Specialty Chemicals is now Nouryon". GlobeNewswire News Room. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Top companies: Most profitable Archived 19 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, CNNMoney.com, Retrieved on 4 March 2009.

- "AkzoNobel Report 2015". AkzoNobel. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "AkzoNobel Report 2014" (PDF). AkzoNobel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

-

Dawson, Brian (27 January 2012). "Plastic Expansion". NYSE Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012.

Expancel microspheres from AkzoNobel can swell to as much as 60 times their original volume.

-

"AkzoNobel investing €30 million to meet demand for Expancel". Dutch Daily News. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011.

AkzoNobel is boosting capacity in Sweden for its Expancel expandable microspheres in order to meet growing global demand.

-

Gerlin, Helen (23 May 2001). "Akzo Nobel anmäls för arbetsmiljöbrott" [Akzo Nobel reported for safety violations]. Dagbladet. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

Expancel vid Akzo Nobel byggs ut och moderniseras – ett projekt som sysselsätter ett flertal arbetare från olika företag. (Expancel at Akzo Nobel is being expanded and modernized - a project that employs numerous workers from different companies.)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Scott, Alex. "Akzo Nobel adds capacity for Expancel spheres.(expandable polymer spheres, Sweden)(Brief Article)." Chemical Week. IHS Global, Inc. 2003. HighBeam Research. 2 Jun. 2012 <http://www.highbeam.com>. (subscription required) Archived 31 March 2002 at the Wayback Machine

- "AkzoNobel Report 2017". AkzoNobel. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Report for the 2010 and the 4th quarter Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

.svg.png)