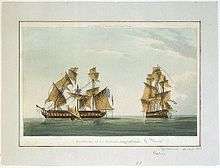

Action of 10 August 1805

The Action of 10 August 1805 was a minor naval engagement between two frigates of the British Royal Navy, HMS Phoenix and the French Navy Didon as part of the Napoleonic wars.[3] After an hour of action Didon surrendered to Phoenix.[1]

Background

Thomas Baker took command of HMS Phoenix on 28 April 1803.[4][5] He was assigned to the Channel Fleet under Admiral William Cornwallis, and on 10 August 1805 he came across the 40-gun French frigate Didon off Cape Finisterre.[4][6]

Prior to the sighting Phoenix had intercepted an American merchant, en route from Bordeaux to the United States. The American master had been invited onto Phoenix, sold the British some of his cargo of wine, and had toured Phoenix before being allowed to continue on his way.[7] Phoenix had at this time been altered to resemble from a distance a large sloop-of-war. Didon, which was carrying despatches instructing Rear-Admiral Zacharie Allemand's five ships of the line to unite with the combined Franco-Spanish fleet under Vice-Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve, intercepted the American merchant and from him received news that a 20-gun British ship was at sea and might be foolish enough to attack Didon.[7]

Didon's commander, Captain Captain Pierre Milius, decided to await the arrival of the British ship, and take her as a prize.[7]

Battle

On 10 August 1805, the two vessels met off Cape Finisterre. Phoenix was able to approach and engage Didon before the French realised that she was a larger frigate than they had anticipated.[7] At 8am Didon hoisted French colours and an hour later the fighting commenced. Didon opened fire upon Phoenix still coming down but Phoenix made no return and Captain Baker intended to pass and engage to leeward of the French ship. In the meantime Didon raked the British frigate while Baker therefore determined to close with his adversary.[7] Phoenix ranged up alongside Didon and engaged within pistol shot but was to far windward and having too much way upon her soon drew ahead of the French ship.[1] Didon took advantage of this by luffing across the stern of Phoenix and poured in a raking broadside.[2] She then bore up and again raked Phoenix and was about to do this again but Baker counteracted the movement. The French crew then made a vigorous but unsuccessful attempt to board in which the Royal Marines were able to repel the French boarders.[8] After this had lasted about three quarters of an hour a breeze sprung up and caused Didon to forge ahead by which more guns from Phoenix were brought to bear and they became again engaged broadside to broadside. The superiority of the fire of Phoenix however soon began to tell and after a short time the two ships separated.[1]

Phoenix, having repaired her damages, was about to renew the action when Didon's foremast soon toppled over. This caused more damage to the already damaged foremast leaving her an unmanageable wreck.[8] With this situation and the heavy casualties Didon soon struck her colours at 43°16′N 12°14′W.[3]

The action lasted several hours, with Baker on one occasion having his hat shot off his head.[8] Phoenix had twelve killed and 28 wounded; the French sustained losses of 27 killed and 44 wounded.[2]

Consequences

By intercepting the ship carrying the despatches for Allemand, Baker had unwittingly played a role in bringing about the Battle of Trafalgar, but he was to play an even greater role a few days later, possibly even staving off an invasion of England.[1][6] In 1847 the Admiralty awarded the Naval General service Medal with clasp "Phoenix 10 Augt. 1805" to all surviving claimants from the action.

While sailing to Gibraltar with his prize in tow, Baker fell in with the 74-gun HMS Dragon on 14 August.[6][9] The following day the combined fleet under Villeneuve, heading for Brest and then on to Boulogne to escort the French invasion forces across the Channel sighted the three British ships. Villeneuve mistook the British ships for scouts from the Channel Fleet and fled south to avoid an action.[6][10][11] A furious Napoleon raged 'What a Navy! What an admiral! All those sacrifices for nought!'[10] Villeneuve's failure to press north was a decisive point of the Trafalgar Campaign as far as the invasion of England went, for abandoning all hope of fulfilling his plans to secure control of the Channel Napoleon gathered the Armée d'Angleterre, now renamed the Grande Armée, and headed east to attack the Austrians in the Ulm Campaign.[10][12]

The British ships altered their course and made for Plymouth, where they arrived on 3 September, having prevented an attempt by their French prisoners to capture Phoenix and retake Didon.[13]

Citations

- The Naval and military sketch book, and history of adventure by flood and field. Oxford University. pp. 228–29.

- "No. 15840". The London Gazette. 3 September 1805. p. 1115.

- "No. 15838". The London Gazette. 27 August 1805. p. 1091.

- Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1794–1817. p. 130.

- Tracy (2006), 20.

- Tracy (2006), 20

- James. The Naval History of Great Britain. p. 164.

- James. The Naval History of Great Britain. pp. 168–9.

- James. The Naval History of Great Britain. p. 170.

- Adkin. The Trafalgar Companion. p. 57.

- Mostert. The Line Upon the Wind. p. 470.

- Mostert. The Line Upon the Wind. p. 471.

- James. The Naval History of Great Britain. p. 171.

Bibliography

- Adkin, Mark (2007). The Trafalgar Companion: A Guide to History's Most Famous Sea Battle and the Life of Admiral Lord Nelson. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 1-84513-018-9.

- Dodsley, James (1854). Annual Register. 95. London: F. J. Rivington.

- Barton, Mark (2013). McGrath, John (ed.). British Naval Swords and Swordsmanship. Seaforth Publishers. ISBN 9781848321359.

- James, William (1837). The Naval History of Great Britain: From the Declaration of War by France in 1793 to the Accession of George IV. 4. London: R. Bentley.

- Mostert, Noel (2008). The Line Upon a Wind: The Greatest War Fought At Sea Under Sail: 1793-1815. London: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-7126-0927-2.

- Tracy, Nicholas (2006). Who's who in Nelson's Navy: 200 Naval Heroes. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-244-5.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships of the Age of Sail 1794–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 1-86176-246-1.

_(14773044471).jpg)