ABC (medicine)

ABC and its variations are initialism mnemonics for essential steps used by both medical professionals and lay persons (such as first aiders) when dealing with a patient. In its original form it stands for Airway, Breathing, and Circulation.[1] The protocol was originally developed as a memory aid for rescuers performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and the most widely known use of the initialism is in the care of the unconscious or unresponsive patient, although it is also used as a reminder of the priorities for assessment and treatment of patients in many acute medical and trauma situations, from first-aid to hospital medical treatment.[2] Airway, breathing, and circulation are all vital for life, and each is required, in that order, for the next to be effective. Since its development, the mnemonic has been extended and modified to fit the different areas in which it is used, with different versions changing the meaning of letters (such as from the original 'Circulation' to 'Compressions') or adding other letters (such as an optional "D" step for Disability or Defibrillation).

In 2010, the American Heart Association and International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation changed the recommended order of CPR interventions for most cases of cardiac arrest to chest compressions, airway, and breathing, or CAB.[3]:S642[4]

Medical use

At all levels of care, the ABC protocol exists to remind the person delivering treatment of the importance of airway, breathing, and circulation to the maintenance of a patient's life. These three issues are paramount in any treatment, in that the loss (or loss of control of) any one of these items will rapidly lead to the patient's death. The three objectives are so important to successful patient care that they form the foundation of training for not only first aid providers but also participants in many advanced medical training programs.[5][6][7][8][9]

Hypoxia, the result of insufficient oxygen in the blood, is a potentially deadly condition and one of the leading causes of cardiac arrest. Cardiac arrest is the ultimate cause of clinical death for all animals[10] (although with advanced intervention, such as cardiopulmonary bypass a cardiac arrest may not necessarily lead to death), and it is linked to an absence of circulation in the body, for any one of a number of reasons. For this reason, maintaining circulation is vital to moving oxygen to the tissues and carbon dioxide out of the body.

Airway, breathing, and circulation, therefore work in a cascade; if the patient's airway is blocked, breathing will not be possible, and oxygen cannot reach the lungs and be transported around the body in the blood, which will result in hypoxia and cardiac arrest. Ensuring a clear airway is therefore the first step in treating any patient; once it is established that a patient's airway is clear, rescuers must evaluate a patient's breathing, as many other things besides a blockage of the airway could lead to an absence of breathing.

CPR

The basic application of the ABC principle is in first aid, and is used in cases of unconscious patients to start treatment and assess the need for, and then potentially deliver, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

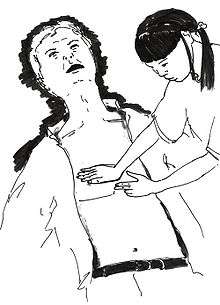

In this simple usage, the rescuer is required to open the airway (using a technique such as "head tilt - chin lift"), then check for normal breathing.[11] These two steps should provide the initial assessment of whether the patient will require CPR or not.

In the event that the patient is not breathing normally, the current international guidelines (set by the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation or ILCOR) indicate that chest compressions should be started.

Previously, the guidelines indicated that a pulse check should be performed after the breathing was assessed, and this made up the 'circulation' part of the initialism, but this pulse check is no longer recommended for lay rescuers. Some trainers continue to use circulation as the label for the third step in the process, since performing chest compressions is effectively artificial circulation, and when assessing patients who are breathing, assessing 'circulation' is still important. However, some trainers now use the C to mean Compressions in their basic first aid training.

Airway

Unconscious patients

In the unconscious patient, the priority is airway management, to avoid a preventable cause of hypoxia. Common problems with the airway of patient with a seriously reduced level of consciousness involve blockage of the pharynx by the tongue, a foreign body, or vomit.

At a basic level, opening of the airway is achieved through manual movement of the head using various techniques, with the most widely taught and used being the "head tilt — chin lift", although other methods such as the "modified jaw thrust" can be used, especially where spinal injury is suspected,[12] although in some countries, its use is not recommended for lay rescuers for safety reasons.[11]

Higher level practitioners such as emergency medical service personnel may use more advanced techniques, from oropharyngeal airways to intubation, as deemed necessary.[13]

Breathing

Unconscious patients

In the unconscious patient, after the airway is opened the next area to assess is the patient's breathing,[11] primarily to find if the patient is making normal respiratory efforts. Normal breathing rates are between 12 and 20 breaths per minute,[14] and if a patient is breathing below the minimum rate, then in current ILCOR basic life support protocols, CPR should be considered, although professional rescuers may have their own protocols to follow, such as artificial respiration.

Rescuers are often warned against mistaking agonal breathing, which is a series of noisy gasps occurring in around 40% of cardiac arrest victims, for normal breathing.[11]

If a patient is breathing, then the rescuer will continue with the treatment indicated for an unconscious but breathing patient, which may include interventions such as the recovery position and summoning an ambulance.[15]

Conscious or breathing patients

In a conscious patient, or where a pulse and breathing are clearly present, the care provider will initially be looking to diagnose immediately life-threatening conditions such as severe asthma, pulmonary oedema or haemothorax.[14] Depending on skill level of the rescuer, this may involve steps such as:[14]

- Checking for general respiratory distress, such as use of accessory muscles to breathe, abdominal breathing, position of the patient, sweating, or cyanosis

- Checking the respiratory rate, depth and rhythm - Normal breathing is between 12 and 20 in a healthy patient, with a regular pattern and depth. If any of these deviate from normal, this may indicate an underlying problem (such as with Cheyne-Stokes respiration)

- Chest deformity and movement - The chest should rise and fall equally on both sides, and should be free of deformity. Clinicians may be able to get a working diagnosis from abnormal movement or shape of the chest in cases such as pneumothorax or haemothorax

- Listening to external breath sounds a short distance from the patient can reveal dysfunction such as a rattling noise (indicative of secretions in the airway) or stridor (which indicates airway obstruction)

- Checking for surgical emphysema which is air in the subcutaneous layer which is suggestive of a pneumothorax

- Auscultation and percussion of the chest by using a stethoscope to listen for normal chest sounds or any abnormalities

- Pulse oximetry may be useful in assessing the amount of oxygen present in the blood, and by inference the effectiveness of the breathing

Circulation

Once oxygen can be delivered to the lungs by a clear airway and efficient breathing, there needs to be a circulation to deliver it to the rest of the body.

Non-breathing patients

Circulation is the original meaning of the "C" as laid down by Jude, Knickerbocker & Safar, and was intended to suggest assessing the presence or absence of circulation, usually by taking a carotid pulse, before taking any further treatment steps.

In modern protocols for lay persons, this step is omitted as it has been proven that lay rescuers may have difficulty in accurately determining the presence or absence of a pulse, and that, in any case, there is less risk of harm by performing chest compressions on a beating heart than failing to perform them when the heart is not beating.[16] For this reason, lay rescuers proceed directly to cardiopulmonary resuscitation, starting with chest compressions, which is effectively artificial circulation. In order to simplify the teaching of this to some groups, especially at a basic first aid level, the C for Circulation is changed for meaning CPR or Compressions.[17][18][19]

It should be remembered, however, that health care professionals will often still include a pulse check in their ABC check, and may involve additional steps such as an immediate ECG when cardiac arrest is suspected, in order to assess heart rhythm.

Breathing patients

In patients who are breathing, there is the opportunity to undertake further diagnosis and, depending on the skill level of the attending rescuer, a number of assessment options are available, including:

- Observation of color and temperature of hands and fingers where cold, blue, pink, pale, or mottled extremities can be indicative of poor circulation

- Capillary refill is an assessment of the effective working of the capillaries, and involves applying cutaneous pressure to an area of skin to force blood from the area, and counting the time until return of blood. This can be performed peripherally, usually on a fingernail bed, or centrally, usually on the sternum or forehead

- Pulse checks, both centrally and peripherally, assessing rate (normally 60-80 beats per minute in a resting adult), regularity, strength, and equality between different pulses

- Blood pressure measurements can be taken to assess for signs of shock

- Auscultation of the heart can be undertaken by medical professionals

- Observation for secondary signs of circulatory failure such as edema or frothing from the mouth (indicative of congestive heart failure)

- ECG monitoring will allow the healthcare professional to help diagnose underlying heart conditions, including myocardial infarctions

Variations

Nearly all first aid organisations use "ABC" in some form, but some incorporate it as part of a larger initialism, ranging from the simple 'ABCD' (designed for training lay responders in defibrillation) to 'AcBCDEEEFG' (the UK ambulance service version for patient assessment).

ABCD

There are several protocols taught which add a D to the end of the simpler ABC (or DR ABC). This may stand for different things, depending on what the trainer is trying to teach, and at what level.[20] The D can stand for:

ABCDE

Additionally, some protocols call for an 'E' step to patient assessment. All protocols that use 'E' steps diverge from looking after basic life support at that point, and begin looking for underlying causes.[27] In some protocols, there can be up to 3 E's used. E can stand for:

- Expose and Examine[2][22] — Predominantly for ambulance-level practitioners, where it is important to remove clothing and other obstructions in order to assess wounds.

- Environment[28][29] — only after assessing ABCD does the responder deal with environmentally related symptoms or conditions, such as cold and lightning.

- Escaping Air — Checking for air escaping, such as through a sucking chest wound, which could lead to a collapsed lung.

- Elimination[26]

- Evaluate — Is the patient "time-critical" and/or does the rescuer need further assistance.

ABCDEF

An 'F' in the protocol can stand for:

- Fundus — relating to pregnancy, it is a reminder for crews to check if a female is pregnant, and if she is, how far progressed she is (the position of the fundus in relation to the bellybutton gives a ready reckoning guide).[30]

- Family (in France) — indicates that rescuers must also deal with the witnesses and the family, who may be able to give precious information about the accident or the health of the patient, or may present a problem for the rescuer.

- Fluids[26] — A check for obvious fluids (blood, cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) etc.)

- Fluid resuscitation[29]

- Final Steps[31] — Consulting the nearest definitive care facility

ABCDEFG

A 'G' in the protocol can stand for

- Go Quickly! — A reminder to ensure all assessments and on-scene treatments are completed with speed, in order to get the patient to hospital within the Golden Hour

- Glucose — The professional rescuer may choose to perform a blood glucose test, and this can form the 'G' or alternately, the 'DEFG' can stand for "Don't Ever Forget Glucose"[32][33]

- Girl Check — Is also used as a reminder that all women of child-bearing age need to be tested for potential pregnancy, as this may guide treatment.

AcBC

Some trainers and protocols use an additional (small) 'c' in between the A and B, standing for 'cervical spine' or 'consider C-spine'.[34] This is a reminder to be aware of potential neck injuries to a patient, as opening the airway may cause further damage unless a special technique is used.

CABC

The military frequently use a CABC approach, where the first C stands for "catastrophic haemorrhage". Violent trauma cases indicate that major blood loss will kill a casualty before an airway obstruction, so measures to prevent hypovolemic shock should occur first.[35] This is often accomplished by immediately applying a tourniquet to the affected limb.

DR ABC

One of the most widely used adaptations is the addition of "DR" in front of "ABC", which stands for Danger and Response.[36] This refers to the guiding principle in first aid to protect yourself before attempting to help others, and then ascertaining that the patient is unresponsive before attempting to treat them, using systems such as AVPU or the Glasgow Coma Score. As the original initialism was devised for in-hospital use, this was not part of the original protocol.[37]

In some areas, the related SR ABC is used, with the S to mean Safety.[19]

DRsABC

A modification to DRABC is that when there is no response from the patient, the rescuer is told to send (or shout) for help and to send some signal to your location' [38][39]

DRSABCD

Incorporates the additional S for shout and D for defibrillation.[40]

MARCH

An expansion on CABC that accounts for the significantly increased risk of hypothermia by a patient due to hypovolemia and the body's subsequent cold weather-like reaction.

- Massive Haemorrhage

- Airway

- Respiratory

- Circulation

- Head injury/Hypothermia

History

The 'ABC' method of remembering the correct protocol for CPR is almost as old as the procedure itself, and is an important part of the history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Throughout history, a variety of differing methods of resuscitation had been attempted and documented, although most yielded very poor outcomes.[41] In 1957, Peter Safar[42] wrote the book ABC of Resuscitation,[1] which established the basis for mass training of CPR.[43] This new concept was distributed in a 1962 training video called "The Pulse of Life" created by James Jude,[44] Guy Knickerbocker and Peter Safar. Jude and Knickerbocker, along with William Kouwenhouen[45] developed the method of external chest compressions, while Safar worked with James Elam to prove the effectiveness of artificial respiration.[46] Their combined findings were presented at annual Maryland Medical Society meeting on September 16, 1960, in Ocean City, and gained rapid and widespread acceptance over the following decade, helped by the video and speaking tour the men undertook. The ABC system for CPR training was later adopted by the American Heart Association, which promulgated standards for CPR in 1973.

As of 2010, the American Heart Association chose to focus CPR on reducing interruptions to compressions, and has changed the order in its guidelines to Circulation, Airway, Breathing (CAB).[47]

See also

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Artificial respiration

- Recovery position

- First aid

References

- Wright, Pearce (2003-08-13). "Obituary: Peter Safar". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- "A systematic approach to the acutely ill patient". Resuscitation Council (UK). June 2005. Archived from the original on 18 July 2005. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, et al. (November 2010). "Part 1: executive summary: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S640–56. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970889. PMID 20956217.

- Hazinski MF, Nolan JP, Billi JE, et al. (October 2010). "Part 1: executive summary: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations". Circulation. 122 (16 Suppl 2): S250–75. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970897. PMID 20956249.

- "First Aid (City of Dearborn MI FD website)". Archived from the original on December 9, 2007. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- Marianne Gausche-Hill (2004). Pediatric airway management. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-2066-7.

- "Emergency Scene Management". Archived from the original on 2009-02-03. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- American College of Physicians; American Academy of Pediatrics (2003). APLS: The Pediatric Emergency Medicine Resource (Fourth ed.). Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7637-3316-2.

- Smith, Roger K.; Joseph S. Sanfilippo (2007). Primary care in obstetrics and gynecology a handbook for clinicians. Norwell: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-387-32327-5.

- Kastenbaum, Robert (2006). "Definitions of Death". Encyclopedia of Death and Dying. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- "Adult Basic Life Support" (PDF). Resuscitation UK Guidelines. Resuscitaton Council (UK): 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2005. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- "Airway Management". Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Grande, Christopher M.; Søreide, Eldar (2001). Prehospital trauma care. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker. pp. 211. ISBN 978-0-8247-0537-4.

- Soar, J; Nolan, J; Perkins, G; Scott, M; Goodman, N; Mitchell, S (2006). Immediate Life Support. Resuscitation Council(UK). ISBN 978-1-903812-12-9.

- "Recovery Position". Archived from the original on 2009-02-03. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- "New CPR Standards". Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- "Emergency Action Plan". Parasol EMT. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- "Assessor's guide to passing your First Aid at Work exam". Mediaid Training Services. Archived from the original on 2018-10-05. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- "The Priority Action Plan". St John New Zealand. Archived from the original on 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- "First Aid: Prehospital Care (Student BMJ website)". Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Cayley, William E Jr (2006-05-01). "Practice guidelines: 2005 AHA guidelines for CPR and Emergency Cardiac Care". American Family Physician. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008.

- Wilkinson, Douglas A; Skinner, Marcus W (2000). Primary Trauma Care (PDF). Primary Trauma Care Foundation. ISBN 978-0-9539411-0-0. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- "Remote Area First Aid Course". Rift Valley Adventures. Archived from the original on 26 January 2004. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- "Emergency First Aid with Level C CPR". Western Canada Fire & First Aid Inc. Archived from the original on 2008-06-09. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- "Cardiac Arrest associated with Pregnancy" (PDF). Circulation. 112: 150–153. 2005-11-28. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.105.166570. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-25. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- Livingston, EH; Livingston, EH; Passare, EP Jr (January 1991). "Resuscitation. Revival should be the first priority". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 89 (1): 117–20. doi:10.1080/00325481.1991.11700789. ISSN 0032-5481. PMID 1985304.

- Tilton, Buck (2004). Wilderness first responder: how to recognize, treat and prevent emergencies in the backcountry. Helena, Mont: Falcon. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7627-2801-5.

- Cass, D; Dubinsky, I; Thompson, M; Freedman, M; Klompas, M (2000). Emergency Medicine (PDF). MCCQE. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- Accident Compensation Corporation (June 2007). Management of burns and scalds in primary care. New Zealand Guidelines Group.

- Fisher, Joanne; Brown, Simon; Cooke, Matthew; Walker, Alison; Moor, Fionna; Crispin, Pam. UK Ambulance Services Clinical Practice Guidelines 2013. Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee/Association of Ambulance Chief Executives/Class Professional Publishing.

- "Pediatric clinical practice guidelines for nurses in primary care". Health Canada. Archived from the original on 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- Clive Roberts. "Acute Poisoning".

- "The perfect crime". Student BMJ.

- Occupational First Aid. Level 5 (PDF). Further Education and Training Awards Council. July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- The military's use of advanced medical techniques in emergency care on the battlefield

- "The primary survey". St John Ambulance. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- Committee on CPR of the Division of Medical Sciences, National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, JAMA 1966;198:372-379 and 138-145.

- Stebbing, James. "The Primary Survey" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-21. Retrieved 2008-12-19.(website no longer in operation)

- Gibson, Tracey; Cole, Elaine; McLeod, Anne. "Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation" (PDF). Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning.

- Morley, J and Sprenger C (2012), First Aid Handbook, Highfield

- "Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (Charles University School of Medicine website)". Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Mitka, M (May 2003). "Peter J. Safar MD "Father of CPR" Innovator, Teacher, Humanist". JAMA. 289 (19): 2485–2486. doi:10.1001/jama.289.19.2485. PMID 12759308.

- Robinson, K. "A student paramedic's tribute to Peter Safar" (PDF). Journal of Emergency Primary Health Care. 1 (1–2). Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- "A Shock to the System". Archived from the original on 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- "The Engineer Who Could (Hopkins Medical News website)". Archived from the original on 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Safar, P; Escarraga L; Elam J (1958). "A comparison of the mouth to mouth and mouth to airway methods of artificial respiration with chest pressure arm lift methods". N Engl J Med. 258 (14): 6710–6717. doi:10.1056/NEJM195804032581401. PMID 13526920.

- Hazinski, M. F., ed. (October 2010). Highlights of the 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resucitaion and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. American Heart Association. pp. 2–7.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: First Aid |