2015 Ocotlán ambush

On 19 March 2015, a convoy of the National Gendarmerie, a subdivision of the Mexican Federal Police (PF), was ambushed by gunmen of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), a criminal group based in Jalisco, Mexico. The attack occurred in a residential neighborhood in Ocotlán, Jalisco. Five policemen, four CJNG gunmen, and two civilian bystanders were killed. According to police reports, as the PF convoy pulled up next to a parked vehicle, gunmen shot at them from the vehicle and from rooftops. The police attempted to shield themselves using their patrol cars, but reinforcements from the CJNG arrived at the scene and overwhelmed them. The shootout lasted between thirty minutes to two hours before the CJNG fled the scene.

| 2015 Ocotlán ambush | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mexican Drug War | |||

State of Jalisco in Mexico | |||

| Date | 19 March 2015 9:15 p.m. (approximately) | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Unconfirmed; multiple motives suggested | ||

| Resulted in | 11 dead; 5 wounded; 26 vehicles and 31 houses damaged | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

| 2 (civilian bystanders) | |||

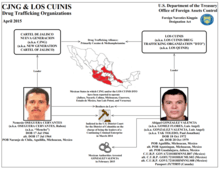

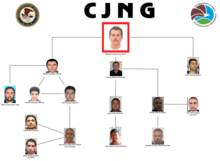

The attack was one of the deadliest incidents against security forces during the administration of President Enrique Peña Nieto, and the first and deadliest against the National Gendarmerie, at that time the newest police force in Mexico, in the ongoing Mexican Drug War. The attack made national headlines and prompted reactions from the highest levels of the Mexican government. The motives behind the ambush remain unclear, but many have been proposed, including one that suggests that the gunmen ambushed the police to protect their leader, Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes (alias "El Mencho"), who was reportedly in the vicinity.

Over the years, multiple suspects have been arrested, including high-ranking members of El Mencho's security group and officers from Ocotlán's municipal police force. Authorities believe the policemen arrested worked for the CJNG and aided them during the ambush. Law enforcement presence in Ocotlán increased after the ambush, but violent confrontations between the CJNG and security forces continued throughout the rest of 2015 in Jalisco and neighboring states.

Background and possible motives

The attack was one of the deadliest incidents against security forces during the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto (2012–2018),[1] and the first and deadliest against the National Gendarmerie (es) – at that time the newest police force in Mexico – in the ongoing Mexican Drug War (2006–present).[2][3] In addition, the attack was the third deadliest against any part of the Mexican Federal Police (PF) force since 2006.[4] The National Gendarmerie was created on 22 August 2014 by Peña Nieto to combat crime in Mexico.[5] All of the officers had received training from the Army and had not been part of any other police force prior to joining.[6] The cadets were mostly young, college-educated recruits, and they were recruited without previous police training under the rationale that this prevented corruption in the National Gendarmerie's ranks.[7] The commanders of the units were trained by police forces in the United States, Colombia, Chile, Spain, and France.[6] The force was initially made up of 5,000 officers,[8] and was a subdivision of the PF, which consisted of roughly 36,000 members when the National Gendarmerie was created. Though members were required to have military training, the National Gendarmerie was intended to be a civil police force capable of a rapid response to crime.[7]

Since late November 2014, around 300 National Gendarmerie officials had been stationed in Ocotlán to safeguard the borders of Jalisco–Michoacán and Jalisco–Guanajuato, and prevent the incursion of the Knights Templar Cartel, a Michoacán-based criminal group and a rival gang to the CJNG.[9][10] They conducted patrols after there were reports of cargo theft in the region.[11] Weeks prior to the ambush, law enforcement officers carried out several covert operations in Ocotlán and the entire Ciénega area. According to intelligence reports, they had information that the suspected CJNG leader, Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes (alias "El Mencho"), was in the area.[9] On the day of the attack, the police reportedly had information that El Mencho was in a meeting in Oxnard street, in the neighborhood where the attack occurred.[12] Investigators believe that the CJNG carried out the attack to restrict the mobility of the security forces and allow El Mencho to escape from the area.[13] They also suspected that the CJNG planned the attack as a retaliation for attempted crackdowns against El Mencho, who became one of Mexico's most-wanted following the arrest of Servando Gómez Martínez (alias "La Tuta"), the suspected leader of the Knights Templar Cartel.[9]

Besides the proposal that the PF was in the area to apprehend El Mencho, other sources suggested different motives. One version suggests that the policemen were in the neighborhood investigating a previous attack against the local police.[14][15] Another account states the policemen were heading to a house in Centenario street.[16] An account cited by a PF official stated that the attack was carried out because the CJNG was moving a large shipment of narcotics to Ocotlán and wanted to prevent the police from intervening.[17] Another report suggests that the CJNG was in the area for a meeting with municipal policemen from Ocotlán. After the meeting went wrong, the policemen called the PF as reinforcements, and the CJNG did the same with their gunmen; when the PF reached the scene, the shootout reportedly broke out.[18] An account cited by federal government sources suggests that the policemen were ambushed after one of the senior officers in the convoy noticed that a woman was being abused by a man. When the policemen got out of their vehicles and tried to stop the man, they noticed he was armed and guarded by a large number of gunmen, who outnumbered them; the shootout reportedly broke out after this.[19]

The attack set a precedent for the PF, as it had not recorded casualties in Jalisco prior to the attack. According to government sources, the PF had two deadlier attacks prior to the incident in Ocotlán: on 27 May 2008 in Culiacán, Sinaloa, 8 PF officers were killed in a shootout with gunmen from the Beltrán Leyva Cartel;[20][21] on 13 July 2009 in La Huacana, Michoacán,[22] 12 PF officers were killed by La Familia Michoacana.[lower-alpha 1][20] However, the attack in Ocotlán demonstrated to police that the manpower and level of coordination of the CJNG was greater than they had expected.[23] Investigators analyzed the offensive actions of the CJNG after the Ocotlán incident, and drew comparisons with their modus operandi during the 6 April 2015 attack that left 15 PF officers dead in San Sebastián del Oeste. They concluded that in their ambushes against security forces, the CJNG was employing a similar strategy. The CJNG would cut off their victim's vehicles from the road, have numerical superiority in foot soldiers and vehicles, and use a large arsenal of weapons and explosives to attack and overwhelm security forces.[24]

Ambush and shootout

.png)

At 9:15 p.m. on 19 March 2015,[25] seven vehicles from the National Gendarmerie drove through a street in the La Mascota neighborhood of Ocotlán, Jalisco.[lower-alpha 2][27] As one of the police vehicles moved alongside a white car parked near the sidewalk, several gunmen from that vehicle began shooting at the police officers with high-caliber rifles.[28] Other gunmen reportedly shot at the officers from rooftops.[29] The ambush forced the policemen to take cover, using their vehicles as shields while they prepared to return fire.[30] However, as the policemen tried to protect themselves from the gunfire, twelve vehicles with additional gunmen arrived at the scene and began attacking them from several directions.[31] In total around 40 CJNG gunmen participated in the attack.[29] The shootout lasted between thirty minutes and two hours.[lower-alpha 3] It extended to nearby streets as the gunmen continued to fire their weapons while attempting the flee the scene.[10] Eleven people were killed in the attack:[33] five of them were officers from the National Gendarmerie;[34] four were from the CJNG; and two were civilian bystanders who were killed in the crossfire.[35] Five officers were wounded,[36] though only one of them was reportedly in a serious condition;[37] all of them were hospitalized.[38][39]

During the shootout, a person in the neighborhood recorded the sound of the gunfire for approximately a minute-and-a-half.[40] After the shootout, Mexican authorities seized eighteen assault rifles, ten handguns, two fragmentation grenades,[lower-alpha 4][42] and five vehicles used by the perpetrators.[43] The Jalisco attorney general, Luis Carlos Nájera Gutiérrez de Velasco, said that twenty-nine vehicles and thirty-one houses in the neighborhood were damaged by the gunfire.[44] Seven of the twenty-nine vehicles damaged were owned by the National Gendarmerie, seventeen were owned by civilians, two were motorcycles, and three had allegedly been used by the gunmen.[42][45] The damaged vehicles were removed from the neighborhood the next day.[46] The street where the attack took place had several large bloodstains from those killed and wounded.[47] According to investigators from the Jalisco Institute of Forensic Sciences (IJCF), over 2,000 bullet casings were found at the scene, most of them from high-caliber rifles. The investigation and evidence collection at the scene was first conducted by the Government of Jalisco,[48] but the case was transferred to federal jurisdiction and given to Mexico's Attorney General's Office (PGR).[lower-alpha 5][11]

The government did not immediately state which criminal group it believed was responsible for the attack.[38] The Jalisco State Police and the Mexican Army arrived in Ocotlán after the attack and conducted a search along the area's dirt roads and highways close to the border with Michoacán, one of the states adjacent to Jalisco, in an attempt to locate those responsible.[50] Law enforcement explained that the Jalisco State Police took longer than usual to arrive at the scene after the National Gendarmerie called them for support because they were at the Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 2 (also known as "Puente Grande"), a maximum-security prison in Jalisco, carrying out an inspection.[42]

Immediate reactions

Immediately after the shootout ended, the neighborhood was flooded with police officers and ambulances. Only two Televisa reporters and one cameraman were able to reach the ambush scene to report what occurred on national television, but an officer warned them to stay away from the scene because law enforcement was on high alert for a further attack. Local people who were on their way home were not able to get there due to several police roadblocks. The Mexican Red Cross team in Ocotlán said that fireworks from a festival the previous night at the San José Church, a congregation close to where the ambush occurred, had masked the gunfire noises from the ambush. The head of the Red Cross said his team was not able to provide first aid for an attack of this scale, hence they had contacted the Red Cross in Guadalajara to provide assistance. Through the night, police checkpoints were set up in Ocotlán, and at least two military helicopters flew over the neighborhood for several hours.[51] Electricity supply and telephone service was cut off for the entire night because lightpoles had been damaged by the gunfire.[29]

On 20 May, the PF, Army, PGR, and Jalisco state authorities conducted an investigation at the scene and patrolled the vicinity before leaving without making an official announcement. Information about the attack continued to only be provided by media outlets and civilians, who shared images of the corpses, the property damage, and the bloodstained streets on social media.[52] Municipal policemen also patrolled Ocotlán in police cars or on motorcycles or bicycles. Neighbors highlighted the fact that the local policemen were unusually calm and were not wearing bullet-proof vests. They stated that the PF, on the other hand, looked nervous. Others said they saw several CJNG scouts monitoring the area and passing on information to their superiors regarding the presence and mobility of law enforcement personnel.[18]

Later that afternoon, the PF chief Enrique Francisco Galindo Ceballos (es) confirmed the attack in a joint communiqué with the National Security Commission (CNS) (es). On Twitter, Galindo Ceballos honored the officers killed, and stated that they gave their lives to protect their communities.[53] He also asked civilians to anonymously report any information about the Ocotlán ambush to the police.[54] Secretary of the Interior Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong also condemned the attack and issued condolences to the families of the police officers killed. He reiterated that efforts against organized crime would continue. Nájera Gutiérrez de Velasco confirmed that the attack was carried out by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG).[11] He also admitted that Ocotlán was a major hub for cargo theft, though he clarified that investigators did not have information about an organized crime group with the capacity of the CJNG operating in the area.[30] Following the attack the authorities stated that they were coordinating their efforts with the Mexican Navy and Army to increase security measures in the region.[43]

Interviews and testimonies

Residents interviewed at the scene stated they were surprised and scared by the shootout.[55] One of them explained that when the shootout occurred outside her home, everyone in her household threw themselves to the ground to avoid being shot. They said they were unaware that one of the houses in the neighborhood, No. 562, was being used by an organized crime group.[46] Others complained that the bloodstains on the street from those wounded or killed during the ambush were not cleaned by the authorities after the attack.[56] Some of them said that the CJNG took several of those wounded from the scene.[16] A number of them told the press that the casualties from the shootout were thereby higher than the government had reported;[9] according to several residents, seven National Gendarmerie members were killed, and there were between fourteen and sixteen casualties in total.[57] At the San Vicente Hospital, a private hospital in Ocotlán, unconfirmed reports stated that twenty people were hospitalized after the shootout. At the Mexican Social Security Institute, thirty more were reported. Sources consulted by the press were not able to determine if the people in these two hospitals were there to receive medical attention for gunshot wounds, minor injuries, or shock, as both hospitals were unable to provide information without legal authorization from the government.[9]

In addition, school classes were cancelled in Ocotlán on 20 May after authorities recommended it as a "preventative measure".[17] This included the University Center of the Ciénega.[9] The local police reported that at one of the schools, students found abandoned assault rifles on the floor. They believe these weapons were left behind by the suspects involved in the shootout as they tried to escape the scene.[17] The shootout occurred on Thursday, and classes restarted on Monday, 23 March.[58] The mayor of Ocotlán, Enrique Robledo Sahagún, spoke to the press about the attacks and refuted the idea that the city was going through a "cockroach effect",[59] a term used in Mexico to describe how the presence police efforts in one area allows organized crime to operate more freely elsewhere.[60] He denied that organized crime members from Michoacán were using Ocotlán, which lies on the Jalisco–Michoacán border, as a corridor. He claimed the attack was an "isolated incident" and that he would make sure the families of the civilians killed received support from the local government.[59] He also said it was natural for civilians in Ocotlán to be scared, that the situation would return to normality, that he had not received any death threats, and that he was not collaborating with organized crime.[61]

There were several rumors circulating in Jalisco's Ciénega Region (es), where Ocotlán is located, of other shootouts between security forces and organized crime groups.[39] Many businesses and schools did not open the following day due to rumors and fears of other attacks. The same day, authorities received several calls and messages on social media with allegations of attacks by organized crime.[62] However, authorities clarified that the rumors were false.[39] Nájera Gutiérrez de Velasco criticized the rumors and said that he believed they were likely started by organized crime groups to cause confusion. He specifically said that organized crime groups may create rumors to force law enforcement to deploy to other areas and facilitate their operations where security measures are high. To prevent this from occurring, he said that federal authorities were coordinating with the local police to spread their presence and prevent organized crime from having operational flexibility.[63] Nájera Gutiérrez de Velasco mentioned two days after the shootout that civilians were able to renew their daily activities as usual, but did recognize that the risk of civilian bystanders being caught in a crossfire existed.[62]

Reactions

Civilian

A week after the attacks, on 26 March, several students from Ignacio Manuel Altamirano Middle School No. 24, the school where one of the civilians killed had studied, created an art piece on the school grounds using sawdust. The artwork was intended to promote peace awareness.[64] The students also wrote several cards to the mayor of Ocotlán, asking him to help restore peace in their city and to ask the security forces to leave Ocotlán.[65] On 27 March, a local TV station uploaded a short video online in memory of the deceased student.[66] The following day, between 200 and 300 civilians dressed in white organized a peaceful march to protest against the violence in Ocotlán.[lower-alpha 6][68] The marchers gathered at the city's main square after organizing their efforts through Facebook.[69] The organizers stated that the march was apolitical in nature; they also stated they were not only protesting against violence, but asking for peace and the demilitarization of Ocotlán. Among the protesters were relatives of the civilians killed in the ambush, who complained that no one in the Mexican government, including the mayor, had reached out to them to provide assistance. Other protesters complained that the military operations and home invasions were disturbing the tranquility of their community.[67] When they gathered at the main square, the protesters read a pamphlet that was signed by several locals and directed to the authorities. However, the protesters were upset that the mayor was not present during the event. They gave the document to one of the mayor's public security heads.[57]

On 30 March, civilians organized a second march in Ocotlán; this time with over 5,000 attendees, including Cardinal Francisco Robles Ortega.[57] He was accompanied by 10 priests from the archdiocese.[70] Robles Ortega told the protesters that it was the duty of the government to protect civilians as part of the social contract between both parties. He also stated that praying was not enough: "It's not only about asking. It's not only about praying; it's also about acting". This second march was also organized online and by local churches across Ocotlán.[57] The march concluded in the evening with a mass conducted in the city's main square. Most of the attendees were dressed in white and were from all age groups. In the religious ceremony, Robles Ortega asked the families to take care of their children because they could easily fall prey to organized crime. He also asked citizens to be brave and report crimes to the authorities, and that not doing so made them accomplices of criminal activity. Before the mass concluded, the attendees read a prayer together, and Robles Ortega closed the ceremony by talking about the importance of building a peaceful society together.[71]

Government

On 20 March, Secretary of the Interior Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong posted a message in his Twitter account thanking the five officers killed in the ambush for their commitment to their duty.[72] He also sent his condolences to the officers' families and colleagues,[73] and stated that the government was working diligently to ensure public security.[74] The same day the head of the CNS, Renato Sales Heredia, instructed National Gendarmerie chief Manelich Castilla Craviotto and Jalisco attorney general Jesús Eduardo Almaguer Ramírez to hold a ceremony at the scene where the ambush occurred in memory of the officers killed. Along with the mayor of Ocotlán, members of the Mexican Army, and other members of the PF, they publicly recognized their work, and stated that the crimes would not go unpunished. They stated that the government was committed to restoring peace in Mexico and that the ambush had helped to unify Mexico's security forces. At the end of the ceremony, civilians and government officials held a moment of silence in memory of the officers and civilians killed. This ceremony was carried out simultaneously with others at the PF headquarters in Mexico City and in other National Gendarmerie stations.[75]

The following day, Galindo Ceballos held another ceremony in memory of the officers at the PF hangar in the Mexico City International Airport.[76] The bodies of the five officers lay inside coffins, wrapped in the flag of Mexico. Galindo Ceballos thanked the officers for their services, and then went directly to the victims' families and told them that the government would support them.[77] Osorio Chong and former CNS chief Monte Alejandro Rubido García also expressed their solidarity with the officers' families. During the ceremony, Galindo Ceballos read the names the officers killed while the officers present yelled "present" for each of them. The PF then performed a three-volley salute and gave the family members a flag of Mexico and a sculpture. The ceremony concluded after the PF played their anthem and the Mexican National Anthem.[78] On 24 March, the Senate of the Republic held a moment of silence as a senate tribune in memory of the officers and civilian bystanders killed in the ambush. They condemned the attacks and wrote a decree stating that the government should pursue an investigation to bring the perpetrators to justice.[79]

Nájera Gutiérrez de Velasco explained that attacks against security forces were "nothing new" in Jalisco. He told the press that civilians should only be concerned if the government were inactive and suspected gangsters were roaming the streets freely, and suggested that this was the case in some parts of Jalisco.[63] He explained that when security forces crack down on organized crime, they run the risk of suffering attacks like the one in Ocotlán.[80] He emphasized that the government had a responsibility to go after organized crime despite these risks. He clarified that the attacks were directed towards law enforcement and not against civilians. He went on to blame criminal groups for carrying out attacks against law enforcement personnel where civilians were at high risk, and stated that law enforcement officers in Mexico were attempting to operate with more caution than organized crime when dealing with civilians. He concluded the interview by asking civilians to remain calm and trust law enforcement efforts against organized crime groups.[63]

On 22 March, a few days after the ambush occurred, Gutiérrez de Velasco asked Ocotlán residents to ignore rumors of shootouts in the area and to stay alert for phone extortions. He stated that there were multiple rumors of shootouts in the area, and that organized crime members were creating them to distract security forces and allow some of their members to escape from the area that the authorities had under surveillance. Itzcoatl Tonatiuh Bravo Padilla, the rector of the University of Guadalajara, confirmed that classes would restart at all schools in Ocotlán the following day. He said that schools were working with the government to coordinate their security measures, and that additional security would be sent to their campuses. The majority of their student body had not attended classes since 19 March, when the shootout occurred, because of fears of future attacks.[81]

On the anniversary the attacks, the PF held another ceremony in the street where the ambush took place.[82] In a speech, Castilla Craviotto said that they held the ceremony there because the ambush scene was important for the National Gendarmerie since it was the first time in the police force's history that they had lost members while on official duty. He added that the National Gendarmerie was committed to continuing their fight against organized crime. Almaguer Ramírez, other state officials, and members of the Army's 92 Infantry Battalion attended the ceremony. Ocotlán's mayor, Paulo Gabriel Hernández Zague, spoke to the press during the ceremony and expressed his discontent with the lack of support from the federal government. He said that the federal government had reduced public funding for Ocotlán after the attacks; the funding removed was for the Subsidy for Municipal Public Security (Spanish: Subsidio para la Seguridad en los Municipios, SUBSEMUN), and included over MXN$11 million in equipment for Ocotlán's municipal security forces. He stated that Ocotlán needed this funding to continue its security efforts.[83]

Memorial for officers

As part of the commemorations, the PF published a report with the photos and names of the officers, and a short biography of their service:[84][85]

| Name | Hometown | Rank | Short description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salvador Flores Bautista | Atlixtac, Guerrero | Lead officer | Commemorated by the PF for his conviction, professionalism, and objectivity. | [86] |

| José Adán Álvarez Hernández | San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosí | Police officer (3rd Rank) | Commemorated by the PF for his discipline and trustworthiness. | [86] |

| Enrique González Santa María | Mexico City | Police officer (3rd Rank) | Commemorated by the PF for his service to civilians and his dedication. | [86] |

| César Gómez Cruz | Puebla, Puebla | Police officer (2nd Rank) | Commemorated by the PF for his courage, dedication, and loyalty. | [86] |

| Cristhian Yobani López Becerril | State of Mexico | Police officer (3rd Rank) | Commemorated by the PF for his altruism and public service activities. | [86] |

Police reforms in Ocotlán

On 24 March 2015, the Government of Jalisco discussed the possibility of taking over government functions in Ocotlán and disarming the Ocotlán Municipal Police; measures similar to those they had taken with the police forces of Cocula and Casimiro Castillo in December 2014. In an interview with the press, Gutiérrez de Velasco stated they were investigating possible links between local officials and organized crime, but was unable to give them more details on the case. He stated that they were working with the federal government on any measures to be taken.[87] However, consideration of taking over the public security functions in Ocotlán began months prior to the ambush. Since 2014, Jalisco's State Public Security Council (Spanish: Consejo Estatal de Seguridad Pública, CESP) had identified two policemen in Ocotlán, out of the 1,324 registered officers, as "high risk" employees who it was thought likely that they had colluded with organized crime groups.[4]

Other issues in Ocotlán's police force caught the attention of the state government after that. On 24 January 2015, four officers from Ocotlán's police force were arrested for their alleged participation in the sexual harassment of a sixteen-year-old girl. According to the testimonies of the detainees, Ocotlán policemen forced the minor to engage in sexual activities with them and other members of the police force for at least two years. The officers involved in the plot were charged with sexual harassment of a minor and human trafficking.[4] The disarmament discussion became a priority in early 2017, when several high-profile violent incidents occurred in Ocotlán.[88] In early 2017, a 17-year-old high school medical student from Ocotlán was killed in a shootout after armed men attacked him and a group of friends. Weeks later, several employees from Reporte Jalisco newspaper were intimidated by the CJNG.[89] Reporte Jalisco print distributors were told by the CJNG to leave Ocotlán or they would be "disappeared". Página 24, another newspaper in the area, also received threats from the CJNG for its coverage of violence in Ocotlán.[90]

On 14 March 2017, the Government of Jalisco disarmed the entire Ocotlán police force and took control of the city's public security functions.[91] According to Ocotlán's mayor Pablo Gabriel Hernández, the ninety-three police officers stationed in Ocotlán were taken to Guadalajara for further training. He stated that none of them were being investigated for potential links with organized crime, though he clarified that ten officers had been dismissed earlier that year after failing performance evaluations.[90] The mayor, however, complained that during the disarmament, state officials were "prepotent" and did not follow established collaboration protocols. He said that state officials "took" the police installations and did not give them time to prepare.[92] Some Ocotlán residents protested in the city's square against the replacement of Ocotlán's police by state level personnel. They stated that they did not want the Jalisco State Police in Ocotlán because of the alleged abuses they carried out against residents. The mayor asked civilians to report any abuses to the local government; protesters complained their past reports had not been responded to.[93]

On 29 April 2017, fifty-three officers from Ocotlán's police force completed training and resumed activities in the city. The training they received included arrest and detention protocols, physical fitness, vehicle inspection, vehicle chases, weapon use, and understanding of Mexico's New Criminal Justice System (Spanish: Nuevo Sistema de Justicia Penal, NSJP). The mayor stated that several of the officers did not have training in these areas or were not up-to-date on their training prior to the disarming the month before. The state government stated in the police officers' graduation ceremony that this training was intended to help officers restore order in Ocotlán and help the municipality grow in economic prosperity.[94]

Investigation and crackdowns

Operations and raids

During the first week after the attack, law enforcement agencies carried out daily operations in Ocotlán with the intention of arresting members of the CJNG.[95] On 22 March,[96] Jalisco state authorities confirmed that they had discovered a property with a zoo in Ocotlán that was presumed to be owned by organized crime gang members.[97] The property was found after the state police patrolled the area close to Ocotlán's toll road booths on the highway that connects Guadalajara with Mexico City.[96][97] Inside the property they recovered three exotic animals: a lion, a tiger, and a bear. Investigators said that the animals were in excellent condition. No suspects were arrested during the operation. The animals were handed over to the Federal Attorney's Office of Environmental Protection (PROFEPA).[98]

On 26 March, police raided a house in the neighborhood where the ambush took place. The military entered the property illegally since they did not have a search warrant, breaking the windows of the door; it was empty as the owner of the house was at work. The mother of the home owner went to the property and told the soldiers that her son worked in the fields and was not involved in organized crime.[64] Outside the house, the military seized a black Ford vehicle that they suspected belonged to the house owner.[95] They later confirmed that the vehicle had been abandoned by the gunmen during the shootout. Neighbors told the press that the military had raided at least ten houses, seized multiple vehicles, and arrested several people that week. The government did not make an official statement about these operations. The Governor of Jalisco, Jorge Aristóteles Sandoval Díaz, told the public that they were actively providing assistance to home owners affected by the attack. However, the neighborhood residents said that the government had not reached out to them for assistance seven days after the attack, and that they had not provided them with assistance to repair the walls of their homes, which were damaged by the gunfire during the shootout.[64]

Arrests and charges

Following the attacks, the PF ordered its seven departments to work on the case, and pledged that they would work diligently to arrest those involved.[99] The federal government ordered an increase in the number of federal troops in Jalisco and the area close to the border with Michoacán by bringing in additional PF members and requesting additional support from the Mexican Army, the Jalisco State Police, and municipal forces. These reinforcements conducted patrols and erected checkpoints to neutralize organized crime groups operating in the area.[100] The Jalisco State Police carried out multiple investigations across the Región Alto area of Jalisco.[101] For security reasons, the government did not disclose the number of reinforcements they had sent to Jalisco. They did confirm that the government would pay for the damages caused by the attack.[100]

On 23 March, the PF arrested two people in Ocotlán for their alleged participation in the ambush. Both of them were in possession of military-exclusive weapons, which is forbidden by Mexican federal law. One of them was sent to Puente Grande, while the other was sent to a special facility for minors as he was underage. Their names were not released to the press; the state government said it was not authorized to do so as the case was under federal jurisdiction.[101] On 31 March 2015, the PF arrested six suspects in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, for alleged participation in the attack.[102]

On 9 June 2015, the PGR arrested four municipal policemen for their alleged participation in the ambush: Raúl Romero Ramírez; David Vázquez Estévez; José Guadalupe Echavarría Arcos; and Jonnathan Alejandro González González.[103] According to investigators, the policemen were working for the CJNG. Authorities confirmed that the arrest was a result of intelligence sharing between the PGR and the PF.[104] Three of the officers were arrested in Jalisco,[105] while one of them was arrested in Puebla after he attempted to escape.[106] They were charged with involvement in organized crime and homicide.[106] The CNS confirmed that additional public servants from Ocotlán were being investigated and had pending arrest warrants.[105] A former municipal police officer, Abraham Pérez Murguía,[107] was arrested about a year later in Ocotlán for his alleged participation in the attack and his involvement in organized crime.[108][109] After his arrest, the officer confirmed that he worked for the CJNG and was involved in the ambush.[110][111]

On 1 September 2015, federal authorities stationed in Zapotlán, Jalisco, confirmed the arrest of Javier Guerrero Covarrubias (alias "El Javi"), a suspected regional leader of the CJNG whom the authorities believe masterminded the Ocotlán ambush.[112] Javier was part of a clan within the CJNG that investigators believe was responsible for providing armed protection to El Mencho.[lower-alpha 7][114] He was also wanted for drug trafficking, extortion, homicide, and kidnapping. At the scene, authorities found him in possession of two assault rifles, one of them equipped with sniper lenses, two handguns, a .38 Super and a 9mm parabellum, and thirteen cartridges.[115] El Javi avoided arrest for at least five months by coordinating his organized crime activities through intermediaries based in several municipalities in Jalisco and Michoacán.[112] Upon his arrest, he was handed over to the Assistant Attorney General's Office for Special Investigations on Organized Crime (SEIDO), Mexico's anti-organized crime investigatory agency, in Mexico City.[112]

On 9 November 2015, the PF was involved in a shootout with alleged affiliates of the CJNG in Ocotlán. In the aftermath, they captured two men who they suspected were involved in the ambush; another gunman who was with them was killed by security forces.[116] According to residents from the Arboledas neighborhood, where the shootout occurred, the house where the suspects were found served as a gathering place for the CJNG. This account was later confirmed by the national press. The PF had gathered intelligence that there were armed men entering and exiting the house. They arrested one individual outside the house and eventually proceeded inside. Once indoors, they were attacked by the CJNG but were able to neutralize them.[117] At the scene, authorities seized one assault rifle, one handgun, and multiple cocaine packages. The three men were part of El Javi's mercenary group; one of them was reportedly the CJNG head of an assassin and extortion squad based in Ocotlán.[116]

On 15 June 2016, undercover PF members arrested Fernando Castillo Rodríguez (alias "El Toro Valencia"), a suspected regional leader of the CJNG.[118] He was believed to have been involved in the ambush.[119] He is the brother of Julio Alberto Castillo Rodríguez, a high-ranking leader of the CJNG and an in-law of El Mencho.[120] According to intelligence reports, Castillo Rodríguez operated in Jalisco but had planned to relocate to the state of Colima, where he was arrested, after security forces came close to discovering his whereabouts. Castillo Rodríguez was arrested without gunfire.[121] While Castillo Rodríguez was being taken into custody, confusion among law enforcement personnel triggered a shootout between the undercover PF officers who apprehended Castillo Rodríguez and state policemen who arrived at the scene. Amid the confusion, one undercover PF officer was killed and another was wounded after they were reportedly believed to be organized crime gang members. Castillo Rodríguez was taken to Mexico City and handed over to the SEIDO, and the PF opened a case to investigate the shootout between the two police forces.[122]

On 31 July 2018, the PF arrested fourteen members of the CJNG in Ocotlán and Cancún, Quintana Roo, in two separate operations.[123] The first operation, which was part of the military-led campaign known as Operation Escudo Titán, was conducted in Ocotlán.[124] Authorities arrested six suspects; according to investigators, these suspects were enforcers of the inner circle of Alonso Guerrero Covarrubias (alias "El 08"), a high-ranking CJNG member and head of El Mencho's security group.[125][126] The CNS stated that they were involved in the ambush as well as in other attacks against security forces. Authorities seized eight assault rifles, more than 1,000 rounds of ammunition, and two stolen vehicles equipped with M-60 machine gun attachments. In Cancún, authorities arrested eight suspects and also seized multiple weapons. This group was charged with twenty homicide cases and extortions in Cancún, but they were not linked to the ambush in Ocotlán.[123]

Aftermath

After the attacks, the government announced that they were increasing their law enforcement presence in the region with more troops from the Army and Navy.[127] Federal authorities said that the CJNG had a geographical advantage by being based in Jalisco and the Guadalajara area. They said that this gave the group access to major drug production areas and drug smuggling routes in the Bajío, the Pacific Ocean, and in the states of Sinaloa, Colima, Nayarit, Guerrero, and Michoacán. These areas were once largely controlled by the Sinaloa Cartel, a Sinaloa-based criminal group, but the CJNG was able to gain access to these areas years prior to 2015.[128]

The Ocotlán ambush was the start of a series of armed conflicts between the PF and the CJNG throughout 2015.[129][29] On 23 May 2015, Heriberto Acevedo Cárdenas (alias "El Gringo"), a suspected regional leader of the CJNG,[130] was killed in a shootout with the Jalisco State Police in Zacoalco de Torres, Jalisco.[131] Three other CJNG members were also killed.[132] According to investigators, El Mencho reportedly ordered the CJNG to carry out attacks against government security forces in Jalisco as retaliation for El Gringo's death.[133][134] On 30 March, suspected CJNG members carried out an attack against Jalisco's security commissioner, Francisco Alejandro Solorio Aréchiga, while he was driving in Zapopan, Jalisco.[135] Over 100 shots were fired in total,[136] but Solorio Aréchiga's bodyguards were able to repel the CJNG's attack and he was unharmed.[135] Investigators confirmed that this was an assassination attempt against Solorio Aréchiga, and that it stemmed from the government crackdowns on the CJNG's leadership.[136] A few days after this incident, the CJNG carried out an ambush in San Sebastián del Oeste and killed fifteen PF officers.[137]

On 22 May, the PF raided a ranch located in Ecuandureo, Michoacán, close to the border with Tanhuato.[138] They suspected that a CJNG cell responsible for the Ocotlán ambush was stationed there.[139][140] Forty-two suspects and one PF officer were killed. The official government account stated that the PF responded to a request to investigate the ranch, where they were attacked.[141] However, human rights organizations and the family of the victims stated that the one-sided victory of the PF suggested that the gunmen were extrajudicially killed, likely as vengeance for previous attacks against law enforcement officers.[142][143] The families stated that some of the corpses were tortured and burned, and that others had their fingers, eyes, or teeth removed.[142] It was later discovered that more than half of the CJNG victims were originally from Ocotlán.[143] The PF denied that the shootout was an extrajudicial killing and stated that the police response was proportionate.[144]

With the death toll of the ambush, the homicide record in Ocotlán for 2015 surpassed the one from the previous year. According to numbers provided by the IJCF after the shootout, Ocotlán registered ten homicides in 2014. The ambush resulted in eleven dead, which increased the death toll for 2015 to twelve. The number of people killed in the ambush, according to the IJCF, equaled the total number of people killed in Ocotlán in all of 2011. The highest death toll registered in Ocotlán in the previous three years was in 2013, when the municipality registered thirteen homicides. Of the forty-eight homicides registered in 2012, 62.5 percent of them were carried out with a firearm, according to figures presented by the IJCF to the press.[145] In Jalisco, 2015 ended with a 10.5 percent increase in complaints of violence from civilians compared to the previous year. In 2014, Jalisco registered 996 complaints; this increased to 1,101 in 2015. In 2016, complaints increased to 1,129, the highest number of complaints registered since 2009.[146]

Two years after the ambush, Ocotlán mayor Hernández Zague stated Ocotlán was still working to recover from the attack. "We are undertaking corrective and preventative measures to change what we once saw in Ocotlán", the mayor said. "But this change does not happen overnight. It is a long process."[146]

See also

Notes

- The source confuses the date with 2010 and the place with Zamora, Michoacán.[20]

- Other sources state that the shootout occurred in the San Juan neighborhood.[26]

- Sources state that the shootout lasted between 30 minutes and over 2 hours.[32][26]

- Other sources stated that authorities seized 7 assault firearms and 4 fragmentation grenades.[41]

- Another source stated that the investigation was undertaken by the PGR and the National Security Commission (CNS) (es).[49]

- Another source stated that there were approximately 50 protesters.[67]

- This group was known as Los Guerreros (The Warriors) and was responsible for a number of attacks against security forces.[113]

References

- Aguiar, Rodrigo (20 March 2015). "Emboscada a policías federales deja al menos 10 muertos en el occidente de México". CNN en Español (in Spanish). Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- "Dan primer golpe a gendarmes". El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015.

- "Tiroteo en Ocotlán deja 10 muertos; 5 eran gendarmes". Hora Cero (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017.

- Herrera, Luis (23 August 2015). "Trata y traición en la Policía". Reporte Índigo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 11 November 2017.

- "Nueve claves para entender la Gendarmería, el nuevo cuerpo policial mexicano". CNN en Español (in Spanish). Turner Broadcasting System. 23 August 2014. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017.

- "Mexico creates special federal force of 5,000 gendarmes to combat widespread economic crime". Fox News Channel. Associated Press. 22 August 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018.

- Archibold, Randal C. (22 August 2014). "Elite Mexican Police Corps Targets Persistent Violence, but Many Are Skeptical". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018.

- Zamarroni, Ulises (20 March 2015). "Mexico ambush kills 10, including 5 federal police". Yahoo! News. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Ocotlán: violencia y miedo". Proceso (in Spanish). 3 April 2015. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- "Policía Federal ajusta a 11 cifra de muertos tras emboscada en Ocotlán". Diario 24 Horas (in Spanish). 20 March 2011. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "El Cártel de Jalisco, detrás del ataque a gendarmes: Fiscal". La Razón (in Spanish). 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018.

- Ferrer, Mauricio (7 April 2015). "Jalisco… ¿en Código Rojo?". Reporte Índigo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 October 2017.

- "La costosa Operación Jalisco". El Diario de Coahuila (in Spanish). 3 May 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- "5 gendarmes, 3 agresores y 3 civiles mueren tras un tiroteo en Jalisco". CNN Expansión (in Spanish). Turner Broadcasting System. 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018.

- "Cinco agentes y un estudiante, víctimas de emboscada en Jalisco". Diario de Juárez (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 11 August 2015.

- "La noche más violenta de Ocotlán, relatan vecinos". El Informador (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017.

- Castillo García, Gustavo; Partida, Juan Carlos (21 March 2015). "Movimiento de droga en Jalisco causó emboscada a gendarmes: PF". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- Levario, Juan (1 April 2015). "Resanado, pintura y silencio sobre balacera en Ocotlán". NTR Guadalajara (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Alzaga, Ignacio (10 June 2015). "Caen 4 municipales por asesinato de gendarmes en Jalisco". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 October 2015.

- Herrera, Luis (5 April 2015). "El asalto a Ocotlán". Reporte Índigo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Cabrera Martínez, Javier (27 May 2008). "Reportan 11 personas muertas tras balacera en Sinaloa". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Castillo, Gustavo (15 July 2009). "Miembros de La Familia mataron a los 12 policías federales: SSP". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 25 June 2017.

- Torres, Raúl (8 April 2015). "Policias, objetivo de cartel; en 20 dias matan a 21". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 March 2017.

- Ángel, Arturo (8 April 2015). "El Cártel de Jalisco pasa a la ofensiva: van 24 elementos policiales muertos en emboscadas". Animal Político (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 September 2015.

- "Gendarmes fueron emboscados en Ocotlán". Un1ón Cancún (in Spanish). El Universal. 23 March 2015. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017.

- Ornelas, Víctor Hugo (21 March 2015). "Ocotlán, un día después del enfrentamiento". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Confirma Policía Federal cinco agentes muertos en Jalisco". Diario de Juárez (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015.

- Flores, Raúl; Luna, Adriana (21 March 2015). "Matan a cinco gendarmes en emboscada en Jalisco". Excélsior (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 25 December 2015.

- Pineda, Leticia (17 April 2015). "Mexico's 'New Generation' cartel takes police head-on". Yahoo! News. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Suman 11 muertos por balacera en Ocotlán". Proceso (in Spanish). 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017.

- "Mueren 10 en enfrentamiento; 5 eran gendarmes". Eje Central (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016.

- "Suman once muertos tras enfrentamiento en Ocotlán, Jalisco". MVS Comunicaciones (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Serrano, Sonia (20 March 2015). "Ya son 11 personas muertas tras balacera en Ocotlán". Milenio Televisión (in Spanish) – via YouTube.

- "Emboscada contra policías deja 10 muertos en Ocotlán, Jalisco". El Financiero (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015.

- "Caen 6 del CJNG por ataques a Policía Federal". Zócalo Saltillo (in Spanish). 1 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018.

- Rello, Maricarmen (23 March 2015). "Dan de alta a policías heridos tras enfrentamiento en Ocotlán". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 31 December 2015.

- Zamarroni, Ulises (20 March 2015). "Once muertos, cinco de ellos gendarmes, en una emboscada en oeste de México" (in Spanish). Yahoo! News. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015.

- "Enfrentamiento entre policías y sicarios deja 11 muertos en Jalisco, México". Univision (in Spanish). 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018.

- "Suman ya 11 decesos por balacera en Ocotlán". Zócalo Saltillo (in Spanish). 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Graban balacera entre sicarios y gendarmes en Ocotlán (+video)". Diario 24 Horas (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Diaz, Lizbeth (20 March 2015). "Gunfight kills 10 after ambush on Mexican police". Reuters.

- Torres, Raúl; Muedano, Marcos (21 March 2015). "Emboscan a gendarmes en Ocotlán". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 August 2015.

- Alzaga, Ignacio; Serrano, Sonia (21 March 2015). "Suman 11 muertos por emboscada en Ocotlán". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 September 2017.

- Tucker, Duncan; Ornelas, Víctor Hugo (10 April 2015). "How the Jalisco New Generation Cartel Is Terrorizing the People of Western Mexico". VICE. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016.

- "CJNG responsable de balacera en Ocotlán". Un1ón Jalisco (in Spanish). El Universal. 21 March 2015.

- Espinoza de los Monteros, Hiram (21 March 2015). "Dan a conocer resultados de enfrentamiento en Ocotlán". Televisa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 July 2018 – via YouTube.

- "Una emboscada narco dejó 10 muertos en México". Infobae (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 13 December 2015.

- "Suman ya 11 decesos por balacera en Ocotlán, Jalisco; autoridades hallan más de 2 mil casquillos". Sin Embargo (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 February 2016.

- "PGR y CNS investigan agresión a federales en Ocotlán, Jalisco". W Radio (in Spanish). 23 March 2015.

- G. Partida, Juan Carlos (20 March 2015). "Balacera entre policías y presuntos sicarios deja 10 muertos en Jalisco". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Rondán, Osvaldo; Suro, Érika (20 March 2015). "Crónica de una balacera de terror en Ocotlán, Jalisco". Revista Zócalo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 March 2015.

- Ornelas, Víctor Hugo (20 March 2015). "Violencia deja marca en Ocotlán". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 January 2016.

- "Confirma PF que efectivos fueron emboscados en Ocotlán". El Universal (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015.

- López Dóriga, Joaquín (20 March 2015). "Confirma PF 10 personas muertas por ataque en Ocotlán". Radio Fórmula (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 July 2015.

- "Enfrentamiento en Ocotlán deja al menos tres muertos y ocho lesionados". Televisa (in Spanish). 20 March 2015 – via YouTube.

- "Campo de batalla". Proceso (in Spanish). 28 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Ramírez Herrera, Marcelo (4 April 2015). "Crece la indignación ocotlense". Proceso (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Reanudarán clases en Ocotlán". Mural (in Spanish). Reforma. 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Alcalde de Ocotlán niega que emboscada a gendarmes sea por 'efecto cucaracha'". La Razón (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Hope, Alejandro (3 November 2011). "¿Existe el efecto cucaracha?". Animal Político (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 15 August 2017.

- Becerra-Acosta, Juan Pablo (8 May 2015). "Del cielo de Jesucristo al infierno de 'El Mencho'". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- "Llega la sicosis tras balacera en Ocotlán". Periódico AM (in Spanish). 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015.

- "Suman 11 muertos por enfrentamiento en Ocotlán, Jalisco". El Diario de Juárez (in Spanish). 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015.

- Martínez, Jorge (27 March 2015). "Operativos invaden Ocotlán luego del enfrentamiento". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 August 2016.

- Hernández, René (27 March 2015). "Temen que se vuelva a repetir la balacera". La Crónica de Hoy (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 July 2018.

- "Isaac Esau Solís, 1999–2015". Vision TV Ocotlán Canal 112 (in Spanish). 27 March 2015. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018 – via YouTube.

- "Se manifiestan contra la violencia en Octotlán". El Financiero (in Spanish). 28 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Zúñiga, Norma (28 March 2015). "Marchan por la paz en Ocotlán". Mural (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 July 2018.

- Quintanilla, Carolina (25 March 2015). "Organizan marcha por la paz en Ocotlán". El Informador (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Jaime, Mariana (30 March 2015). "Pide Ocotlán por la seguridad". Mural (in Spanish). Reforma. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Ortega Camacho, Rebecca (30 March 2015). "Marchan por la paz en Ocotlán, Jalisco" (in Spanish). Vicaría Diocesana de Pastoral. Archived from the original on 20 November 2017.

- "Destaca Osorio valor de policías caídos en Ocotlán". El Universal (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015.

- "Osorio Chong lamenta muerte de gendarmes en Ocotlán". El Informador (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- González Correa, Jorge (20 March 2015). "Osorio da pésame a familias de policías asesinados". Un1ón Hidalgo. El Universal. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015.

- "Rinden homenaje póstumo a elementos de la División de Gendarmería que perdieron la vida en Ocotlán, Jalisco" (in Spanish). Government of Mexico. 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018.

- "Rinden homenaje a gendarmes asesinados". Reforma (in Spanish). 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Rinde homenaje Policía Federal a gendarmes caídos en Ocotlán". Info 7 (in Spanish). 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Ceremonia luctuosa en honor de los elementos de la División de Gendarmería caídos en cumplimiento del deber" (in Spanish). Government of Mexico. 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018.

- "Senado guarda minuto de silencio por elementos de la gendarmería caídos en Ocotlán, Jalisco" (in Spanish). Senate of the Republic. 24 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Pineda Bahena, Teódulo (30 March 2015). "En Ocotlán, alto riesgo de perder la vida en la calle: Fiscal de Jalisco". Los Ángeles Press (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 March 2016.

- "Alertan en Ocotlán por extorsionadores". El Norte (in Spanish). 22 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Rinde Gendarmería homenaje a 5 policías muertos en Ocotlán, Jalisco". Agencia Quadratín (in Spanish). 20 March 2016. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016.

- "Rinden homenaje a gendarmes emboscados en Ocotlán". Milenio (in Spanish). 19 March 2016. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016.

- "Destaca PF semblanza de gendarmes caídos en Ocotlán". El Universal (in Spanish). 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015.

- "Destaca PF semblanza de gendarmes caídos en Ocotlán". El Siglo de Durango (in Spanish). 20 March 2016. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015.

- "Semblanza de los cinco elementos integrantes de la División Gendarmería caídos ayer en el cumplimento de su deber en Ocotlán, Jalisco" (in Spanish). Secretariat of the Interior. 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017 – via Scribd.

- Nájera, Luis Carlos (24 March 2015). "Estudia FGE tomar Ocotlán". Mural (in Spanish). CICSA. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Martínez, Jorge (15 March 2017). "Violencia en Ocotlán llevó a la Fiscalía a intervenir policía". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 November 2018.

- "Por ataque a estudiantes, intervención de la FUR en Ocotlán". Página 24 Jalisco (in Spanish). 16 March 2017. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018.

- Martínez, Jorge (14 March 2017). "Fiscalía interviene policía de Ocotlán". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Blanco, Sergio (14 March 2017). "Fiscalía desarma ahora a Policía de Ocotlán". El Informador (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 November 2018.

- Blanco, Sergio (15 March 2017). "Presidente de Ocotlán se queja por desarme de su Policía". El Informador (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Navarro, Martín (15 March 2017). "Ciudadanos se manifiestan contra Fuerza Única Regional en Ocotlán". RadioUDG (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018 – via University of Guadalajara.

- Ornelas, Víctor Hugo (29 April 2017). "Concluye capacitación de la policía de Ocotlán". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 November 2018.

- "Operativos invaden Ocotlán luego del enfrentamiento". Milenio Televisión (in Spanish). 27 March 2015 – via YouTube.

- "Hallan 'narcozoo' en Ocotlán tras el enfrentamiento". Milenio (in Spanish). 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016.

- G. Partida, Juan Carlos (26 March 2015). "Rescatan animales exóticos de finca del narco en Jalisco". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 November 2017.

- Martínez, Jorge (26 March 2015). "FGE confirma incautación de animales exóticos en Ocotlán". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 August 2016.

- Martínez, César (13 April 2015). "Busca PF a agresores de emboscada". Reforma (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 July 2018.

- Nácar, Jonathan (23 March 2015). "Buscan a los responsables de emboscada en Ocotlán". Diario 24 Horas (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Cae uno por ataque a PF en Ocotlán". El Norte (in Spanish). 23 March 2015. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018.

- Santos, Javier (31 March 2015). "Detienen a seis presuntos delincuentes por hechos violentos ocurridos en Ocotlán". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Dávila, Patricia (9 June 2015). "Caen cuatro policías municipales por emboscada a Gendarmería en Jalisco". Proceso (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Vicenteño, David (9 June 2015). "Caen policías municipales por ataque a Gendarmería en Ocotlán". Excélsior (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 December 2015.

- Huerta, Juan Carlos (9 June 2015). "Caen cuatro implicados en emboscada a policías federales en Jalisco". El Financiero (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 18 August 2015.

- Neri, Antonio (10 June 2015). "Tres policías de Ocotlán detenidos por su presunta participación en emboscada a federales en Jalisco". AF Medios (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 October 2015.

- Baranda, Antonio (10 April 2016). "Cae otro ex policía por ataque a PF". Reforma (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Capturan a ex policía vinculado a emboscada de federales en Ocotlán". Periódico La Verdad (in Spanish). 10 April 2016. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Detienen a expolicía por emboscada contra Gendarmería en Ocotlán". SDP Noticias (in Spanish). 11 April 2016. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016.

- "Detienen a expolicía de Ocotlán por ataque contra elementos federales en Jalisco". López-Dóriga Digital (in Spanish). 11 April 2015. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016.

- "Cae expolicía por muerte de cinco gendarmes en Ocotlán". El Informador (in Spanish). 11 April 2016. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018.

- Ramírez Gamboa, Anel (1 September 2015). "Detienen a 'El Javi', que ordenó emboscada a federales en Ocotlán, Jalisco". El Sol de México (in Spanish). Organización Editorial Mexicana. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Caen 14 del CJNG en Jalisco y Quintana Roo". El Universal (in Spanish). 1 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018.

- "Hermanos Guerrero Covarrubias, claves para Nemesio Oseguera, El Mencho". La Jornada (in Spanish). 3 August 2018. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018.

- Dávila, Patricia (1 September 2015). "Detienen a líder del CJNG involucrado en caso Ocotlán". Proceso (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Vela, Saúl; Huerta, Juan Carlos (9 November 2015). "Tras enfrentamiento en Ocotlán, Gendarmería detiene a sicarios de CJNG". El Financiero (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 December 2016.

- "Caen dos presuntos sicarios del CJNG tras enfrentamiento en Ocotlán". Proceso (in Spanish). 9 November 2015. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018.

- Vicenteño, David (15 July 2015). "Cae 'El Toro Valencia' en Colima". Excélsior (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 September 2017.

- "La PF detiene a integrante del cártel Nueva Generación". El Informador (in Spanish). 15 June 2016. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Cae 'El Toro Valencia', cabecilla del Cártel Jalisco en Colima". Mi Morelia (in Spanish). 15 June 2016. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018.

- "Gendarmería captura en Colima a Fernando Castillo Rodríguez, alias "El Toro Valencia" jefe regional del CJNG". El Independiente (in Spanish). 15 July 2016. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Quiles Cabrera, Alfredo (16 June 2016). "Capturan al Toro Valencia en operativo encubierto". Ecos de la Costa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- "Detienen a 14 en operativos federales en Ocotlán y Quintana Roo". El Informador (in Spanish). 1 August 2015. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018.

- "Policía Federal implementa operativo en Ocotlán". El Informador (in Spanish). 31 July 2018. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018.

- "Caen 14 presuntos miembros de cárteles en Jalisco y Quintana Roo". El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). 1 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018.

- "Detienen en Ocotlán a presuntos custodios de El Mencho". W Radio (in Spanish). 2 August 2018. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Jalisco Nueva Generación, responsable de la balacera en Ocotlán". Sipse (in Spanish). 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015.

- Castillo García, Gustavo (22 March 2015). "El gobierno intensificará los operativos contra el cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- "Arremete contra policías poderoso cártel mexicano como nunca antes". Ríodoce (in Spanish). 16 April 2015. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- Malkin, Elisabeth (7 April 2015). "Mexico: Gunmen Kill 15 Police Officers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015.

- "El historial criminal del jefe del CJNG abatido en Zacoalco". Un1ón Jalisco (in Spanish). El Universal. 24 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- "Jefe de célula del CJNG, una de las víctimas de enfrentamiento en Jalisco". Proceso (in Spanish). 24 March 2015. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017.

- de Mauleón, Héctor (1 June 2015). "CJNG: La sombra que nadie vio" (in Spanish). Revista Nexos. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017.

- Torres, Raúl (8 April 2015). "Policias, objetivo de cartel; en 20 dias matan a 21". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 March 2017.

- Huerta, Juan Carlos (31 March 2015). "Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación ataca a comisionado". El Financiero (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 July 2015.

- Martínez, Jorge (31 March 2015). "Confirman que atentando contra Alejandro Solorio fue venganza". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

- "Fiscalía confirma enfrentamiento en Jalisco; habría 15 muertos". El Financiero (in Spanish). 7 April 2015. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015.

- "Se cultivaba alfalfa en rancho donde ocurrió enfrentamiento" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Milenio. 23 May 2015. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- "Grupo abatido, el mismo que mató a gendarmes en Ocotlán". La Crónica de Hoy (in Spanish). 23 May 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Hernández, René (23 May 2015). "Vinculados con caso Ocotlán son abatidos". La Crónica de Hoy (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- de Mauleón, Héctor (23 March 2015). "Tanhuato: ¿otro asunto de fe?". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 November 2018.

- Partlow, Joshua (30 May 2015). "Residents in a Mexican neighborhood miss the cartel that protected them". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015.

- de Mauleón, Héctor (1 June 2015). "La conexión Ocotlán-Tanhuato". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 11 November 2017.

- Diaz, Lizbeth; Daniel, Frank Jack (19 August 2016). "Police massacre on ranch leaves deep scars in Mexican town". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017.

- "Con víctimas de balacera, Ocotlán superó récord de homicidios del año 2014". Periódico Enfoque Nayarit (in Spanish). 23 March 2015. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018.

- "Deja emboscada huella en Ocotlán". Mural (in Spanish). Reforma. 19 March 2017. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jalisco New Generation Cartel. |