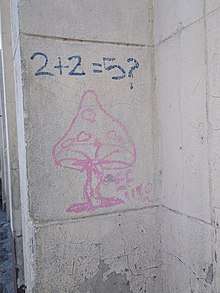

2 + 2 = 5

The phrase "two plus two equals five" (2 + 2 = 5) is used in the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), by George Orwell, as a dogmatic statement of Ingsoc (English Socialism) philosophy, like the slogan "War is Peace", which the Party expects the citizens of Oceania to believe is true. In writing his secret diary in the year 1984, the protagonist Winston Smith ponders if the Inner Party might declare that "two plus two equals five" is a fact. Smith further ponders whether or not belief in such a consensus reality makes the lie true.[1]

.djvu.jpg)

Concerning the falsity of the phrase, in Room 101, the interrogator O'Brien tells the thought criminal Smith that control over physical reality is unimportant to the Party, provided the citizens of Oceania subordinate their real-world perceptions to the political will of the Party; and that, by way of doublethink: "Sometimes, Winston. [Sometimes it is four fingers.] Sometimes they are five. Sometimes they are three. Sometimes they are all of them at once".[2]

As a theme and as a subject in the arts, the anti-intellectual slogan 2 + 2 = 5 has produced literature, such as Deux et deux font cinq (Two and Two Make Five, 1895), by Alphonse Allais, a 19th-century collection of absurdist short stories;[3] and the imagist art manifesto 2 x 2 = 5 (1920), by Vadim Shershenevich, in the 20th century.[4]

Self-evident truth and self-evident falsehood

In the 17th century, in the Meditations on First Philosophy, in which the Existence of God and the Immortality of the Soul are Demonstrated (1641), René Descartes said that the standard of truth is self-evidence of clear and distinct ideas. Despite the logician Descarte's understanding of "self-evident truth", the philosopher Descartes considered that the self-evident truth of "two plus two equals four" might not exist beyond the human mind; that there might not exist correspondence between abstract ideas and concrete reality.[5]

In establishing the mundane reality of the self-evident truth of 2 + 2 = 4, in De Neutralibus et Mediis Libellus (1652) Johann Wigand said: "That twice two are four; a man may not lawfully make a doubt of it, because that manner of knowledge is grauen [graven] into mannes [man's] nature."[6]

In the comedy-of-manners play Dom Juan, or The Feast with the Statue (1665), by Molière, the libertine protagonist, Dom Juan, is asked in what values he believes, and answers that he believes "two plus two equals four".[7]

In the 18th century, the self-evident falsehood of 2 + 2 = 5 was attested in the Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1728), by Ephraim Chambers, which defines the falsehood: "Thus, a proposition would be absurd, that should affirm, that two and two make five; or that should deny 'em to make four."[8] In 1779, Samuel Johnson likewise said that "You may have a reason why two and two should make five, but they will still make but four."[6]

In the 19th century, in a personal letter to his future wife, Anabella Milbanke, Lord Byron said: "I know that two and two make four — & should be glad to prove it, too, if I could — though I must say if, by any sort of process, I could convert 2 & 2 into five, it would give me much greater pleasure."[9]

Politics, literature, propaganda

France

In the late 18th century, in the pamphlet What is the Third Estate? (1789), about the legalistic denial of political rights to the common-folk majority of France, Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès, said: "Consequently, if it be claimed that, under the French constitution, 200,000 individuals, out of 26 million citizens, constitute two-thirds of the common will, only one comment is possible: It is a claim that two and two make five."

Using the illogic of "two and two make five", Sieyès mocked the demagoguery of the Estates-General for assigning disproportionate voting power to the political minorities of France — the Clergy (First estate) and the French nobility (Second estate) — in relation to the Third estate, the numeric and political majority of the citizens of France.[10] Hence the questions and answers of political philosophy posed by Sieyès: "What is the Third Estate? Everything. What has it been hitherto in the political order? Nothing. What does it desire to be? Something"; consequently, the French Revolution (1789–1799) followed the political indifference of King Louis XVI. [11]

In the 19th century, in the novel Séraphîta (1834), about the nature of androgyny, Honoré de Balzac said:

Thus, you will never find, in all Nature, two identical objects; in the natural order, therefore, two and two can never make four, for, to attain that result, we must combine units that are exactly alike, and you know that it is impossible to find two leaves alike on the same tree, or two identical individuals in the same species of tree. That axiom of your numeration, false in visible nature, is false likewise in the invisible universe of your abstractions, where the same variety is found in your ideas, which are the objects of the visible world extended by their interrelations; indeed, the differences are more striking there than elsewhere.[12]

In the pamphlet "Napoléon le Petit" (1852), about the limitations of the Second French Empire (1852–1870), such as majority political support for the monarchist coup d'Ḗtat, which installed Napoleon III (r. 1852–1870), and the French peoples' discarding from national politics the Liberal values that informed the anti-monarchist Revolution, Victor Hugo said: "Now, get seven million, five hundred thousand votes to declare that two-and-two-make-five, that the straight line is the longest road, that the whole is less than its part; get it declared by eight millions, by ten millions, by a hundred millions of votes, you will not have advanced a step."[13]

Russia

.jpg)

In the late 19th century, the Russian press used the phrase 2 + 2 = 5 to describe the moral confusion of social decline at the turn of a century, because political violence characterised much of the ideological conflict among proponents of humanist democracy and defenders of tsarist autocracy in Russia.[14] In The Reaction in Germany (1842), Mikhail Bakunin said that the political compromises of the French Positivists, at the start of the July Revolution (1830), confirmed their middle-of-the-road mediocrity: "The Left says, 2 times 2 are 4; the Right, 2 times 2 are 6; and the Juste-milieu says, 2 times 2 are 5".[15][16][17]

In Notes from Underground (1864), by Feodor Dostoevsky, the anonymous protagonist accepts the falsehood of "two plus two equals five", and considers the implications (ontological and epistemological) of rejecting the truth of "two times two makes four", and proposed that the intellectualism of free will — Man's inherent capability to choose or to reject logic and illogic — is the cognitive ability that makes humanity human: "I admit that twice two makes four is an excellent thing, but, if we are to give everything its due, twice two makes five is sometimes a very charming thing, too."[18]

In the literary vignette "Prayer" (1881), Ivan Turgenev said that: "Whatever a man prays for, he prays for a miracle. Every prayer reduces itself to this: 'Great God, grant that twice two be not four'." [19] In God and the State (1882), Bakunin dismissed deism: "Imagine a philosophical vinegar sauce of the most opposed systems, a mixture of Fathers of the Church, scholastic philosophers, Descartes and Pascal, Kant and Scottish psychologists, all this a superstructure on the divine and innate ideas of Plato, and covered up with a layer of Hegelian immanence, accompanied, of course, by an ignorance, as contemptuous as it is complete, of natural science, and proving just as two times two make five; the existence of a personal god."[20] Moreover, the slogan "two plus two equals five", is the title of the collection of absurdist short stories Deux et deux font cinq (Two and Two Make Five, 1895), by Alphonse Allais;[21] and the title of the imagist art manifesto 2 x 2 = 5 (1920), by Vadim Shershenevich.[22]

In the 20th century, in 1931, the artist Iakov Guminer supported Stalin's shortened production schedule for the economy of the Soviet Union with a propaganda poster that announced the "Arithmetic of an Alternative Plan: 2 + 2 plus the Enthusiasm of the Workers = 5", which exhorted Soviet workers' to realise five years of economic production in four years' time — consequent to Stalin's announcement, in 1930, that the First five-year plan (1928–1933) instead would be completed in 1932, in four years' time.[23]

George Orwell

In propaganda work for the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) during the Second World War (1939–1945), George Orwell applied the illogic of 2 + 2 = 5 to counter the reality-denying psychology of Nazi propaganda, which he addressed in the essay "Looking Back on the Spanish War" (1943), indicating that:

Nazi theory, indeed, specifically denies that such a thing as "the truth" exists. There is, for instance, no such thing as "Science". There is only "German Science", "Jewish Science", etc. The implied objective of this line of thought is a nightmare world in which the Leader, or some ruling clique, controls not only the future, but the past. If the Leader says of such and such an event, "It never happened" — well, it never happened. If he says that "two and two are five" — well, two and two are five. This prospect frightens me much more than bombs — and, after our experiences of the last few years [the Blitz, 1940–41], that is not a frivolous statement.[24]

In addressing Nazi anti-intellectualism, Orwell's reference might have been Hermann Göring's hyperbolic praise of Adolf Hitler: "If the Führer wants it, two and two makes five!"[25] In the political novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), concerning the Party's philosophy of government for Oceania, Orwell said:

In the end, the Party would announce that two and two made five, and you would have to believe it. It was inevitable that they should make that claim sooner or later: the logic of their position demanded it. Not merely the validity of experience, but the very existence of external reality, was tacitly denied by their philosophy. The heresy of heresies was common sense. And what was terrifying was not that they would kill you for thinking otherwise, but that they might be right. For, after all, how do we know that two and two make four? Or that the force of gravity works? Or that the past is unchangeable? If both the past and the external world exist only in the mind, and if the mind itself is controllable — what then?[26]

Contemporary usage

Politics and religion

In the policy debates of the 2009 Iranian presidential election, the reformist candidate, Mir-Hossein Mousavi, accused his opponent, the incumbent president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, of being illogical: "If you ask [the president] what two by two makes, he would answer 'five'." The following political days featured "Two by Two Makes Five!" as one of the slogans chanted by Mousavi's supporters.

In The Cult of the Amateur: How Today's Internet is Killing Our Culture (2007), the media critic Andrew Keen uses the slogan "two plus two equals five" to criticise the Wikipedia policy allowing any user to edit the encyclopaedia. That the cultural enthusiasm of the amateur for user generated content, peer production, and Web 2.0 technology leads to an encyclopaedia of common knowledge, and not an encyclopaedia of expert knowledge; that the "Wisdom of the crowd" will distort what society consider to be truth.[27]

In 2017, the Italian Catholic priest Antonio Spadaro tweeted: "Theology is not #Mathematics. 2 + 2 in #Theology can make 5. Because it has to do with #God and real #life of #people. . . ."[28] Traditionalist Catholics said that Spadaro's remark referred to alleged contradictions, between certain interpretations of Amoris laetitia (2016), an apostolic exhortation on how divorced and remarried Catholics can return to the Church, and the doctrines of Marriage in the Catholic Church. That a person could act counter to Catholic doctrine if he or she felt that God allowed that action, despite the moral and theological contradictions encountered in so acting. Defenders of Spadaro said that he referred to the Catholic view that by human reason alone no person shall ever fully comprehend God. That Spadaro was much like the cynical Rex Mottram character in the novel Brideshead Revisited (1945), by Evelyn Waugh, wherein Mottram, during his catechesis — becoming Roman Catholic to marry a Catholic woman — makes no effort to rationally ascertain any aspect of Catholicism; Mottram attributes all moral and theological contradictions to his personal sinfulness.

Cultural references

In Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged (1957),[29] the hero John Galt posits that "the noblest act you have ever performed is the act of your mind in the process of grasping that two and two make four".

The English rock band Radiohead used the slogan for their 2003 song "2 + 2 = 5".[30]

In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Chain of Command, Part II" (1992), Captain Picard is tortured by a Cardassian in a manner similar to the torture of Winston Smith by O'Brien from Nineteen Eighty-Four. During the episode, the Cardassian officer tries to coerce Picard to admit seeing five lights when in fact there were only four. Picard valiantly sticks to reality. Near the end when Picard is about to be brought back to his crew, he defiantly declares, once again, "There!... Are!... Four!... Lights!" However, later in a counseling session with Troi, Picard admits that he believed he did see five lights at the end.[31][32]

In the Iranian short film Two & Two (2011), a teacher in an authoritarian school uses "2 + 2 = 5" as tool to instill conformity.[33]

In the video game Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, the character Ocelot will repeat "2 + 2 = 5," as one of a few phrases he says after telling the player he has received drug resistance training. This is a reference to Ocelot's own doublethink during the game.[34]

In the video game Orwell, the achievement '2+2=5' is unlocked for ensuring the public acceptance of the Orwell surveillance system and the eradication of Thought, a prominent anti-government movement, therefore ensuring the continued and total control of The Nation's totalitarian government.

Brazilian songwriter Caetano Veloso wrote a song called "Como 2+2" ("Like 2+2" in Portuguese), in which one of the verses translates as "Everything all right like 2 + 2 are 5", a reference to the dictatorship that ruled Brazil then.

In the Sesame Street pitch tape, one of the Muppets suggests the title of the show to be the 2 and 2 Are Five Show; another Muppet turns down the proposed title with the remark "Are you crazy? This is supposed to be an educational show! Two plus two don't make five!"

Dostoevsky's dialogue about two times two equaling five is recited in the 2018 HBO movie Fahrenheit 451.

In business texts about synergy, "2 + 2 = 5" is used without irony to indicate that the outcome of a collective effort is greater than the sum of individual efforts.[35]

See also

- Alternative facts

- Asch conformity experiments – for more on how the influence of a majority can affect how a single person thinks.

- Cultural turn

- Gaslighting

- Epistemic injustice

- Newspeak

- Post-structuralism

- Postmodernity

- Social constructivism

References

- Orwell, George Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), Part Three, Chapter Two, pp. 000–000.

- Orwell, George Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), Part Three, Chapter Two, pp. 000–000.

- Allais, Alphonse (1895). Deux et deux font cinq (2 + 2 = 5) (in French). Ollendorff.

- Шершеневич, Вадим (1920). 2 × 2 = 5: листы имажиниста (in Russian).

- "Descartes' Meditations Home Page". Wright.edu. 27 July 2005. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Wilson, F. P. (1970). The Oxford Dictionary of English Proverbs (3rd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 849. ISBN 0198691181.

- "Moliere Don Juan Adapted by Timothy Mooney". Moliere-in-english.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Chambers, Ephraim (1728). Cyclopaedia; or, an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences . . .Volume the First. London: James and John Knapton et al. p. 11. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- Byron, George Gordon (1974) [Written 1813–1814]. Leslie A. Marchand (ed.). Alas! the Love of Women: 1813–1814. Belknap Press. p. 159.

- Keith M. Baker; John W. Boyer; Julius Kirshner (15 May 1987). University of Chicago Readings in Western Civilization, Volume 7: The Old Regime and the French Revolution. University of Chicago Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-226-06950-0.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 58.

- Seraphita by Honoré de Balzac.

- Long, Roderick T. "Victor Hugo on the Limits of Democracy". Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- e.g. Novoe vremia newspaper ("New Times"), 31 October 1900.

- Bakunin, Mikhail Aleksandrovich. Selected writings. Grove Press : distributed by Random House.

- Bakunin, Michail (1842). "The Reaction in Germany From the Notebooks of a Frenchman". The Anarchist Library – via Internet Archive.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (2010). Orwell: Life and Art. University of Illinois Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780252090226.

- "Notes from the Underground: Part I: Chapter IX by Fyodor Dostoevsky". Classic Reader. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Turgenev, Ivan Dream Tales and Poems, p. 102

- The Communist Manifesto and Other Revolutionary Writings. Dover Publications. 2003. p. 199. ISBN 0486424650.

- Allais, Alphonse (1895). Deux et deux font cinq (2 + 2 = 5) (in French). Ollendorff.

- Шершеневич, Вадим (1920). 2 × 2 = 5: листы имажиниста (in Russian).

- Stalin, Joseph (June 1930). Political Report of the Central Committee to the Sixteenth Congress of the C.P.S.U.(B.). Pravda, No. 177. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Orwell, George. "Looking Back on the Spanish War". orwell.ru.

- "Hermann Göring". Museum of Tolerance Multimedia Learning Center. Archived from the original on 27 December 2004. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- Orwell, George Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), ISBN 0-452-28423-6

- Keen, Andrew (2007). The Cult of the Amateur. Doubleday. pp. 39–40, 44.

- Spadaro, Antonio (5 January 2017). "Theology is not #Mathematics. 2 + 2 in #Theology can make 5. Because it has to do with #God and real #life of #people..." @antoniospadaro. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Rand, Ayn (1999) [1957]. Atlas Shrugged. Plume. ISBN 0-452-01187-6.

- Bloom, Madison (21 February 2017). "10 Songs Inspired by George Orwell's 1984". Paste. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Video on YouTube

- Lapidos, Juliet (7 May 2009). "There Are Four Lights!". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "Two & Two. The Manhattan Short". manhattanshort.com. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- JARVIS (7 September 2015), MGS5: Revolver Ocelot Tranquilizer Easter Egg, retrieved 2 October 2017

- "Synergy - organization, system, company, business, system, History of synergy, Individuals and synergy". referenceforbusiness.com.

Further reading

- Euler, Houston (1990), Reviewed by Andy Olson, "The history of 2 + 2 = 5", Mathematics Magazine, 63 (5): 338–339, doi:10.2307/2690909

- Krueger, L. E. & Hallford, E. W. (1984), "Why 2 + 2 = 5 looks so wrong: On the odd-even rule in sum verification", Memory & Cognition, 12 (2): 171–180, doi:10.3758/bf03198431, PMID 6727639

External links

- "Two Plus Two Equals Red", Time Magazine, Monday, 30 Jun 19