Nations of Nineteen Eighty-Four

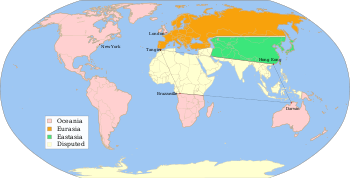

Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia are the three fictional superstates in George Orwell's 1949 dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Since all that Oceania's citizens know about the world is whatever the Party want them to know, how the world evolved into the three states is unknown, and it is also unknown to the reader whether they actually exist in the novel's reality or whether they are a storyline invented by the Party to advance social control. The nations, as far as can be inferred, appear to have emerged from nuclear warfare and civil dissolution over 20 years between 1945 and 1965.

Sourcing

Much of what we know of the society, politics and economics of Oceania and its rivals come from the in-universe book, The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism. The protagonist of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith, describes it as "a heavy black volume, amateurishly bound, with no name or title on the cover. The print also looked slightly irregular. The pages were worn at the edges, and fell apart easily, as though the book had passed through many hands."[1] The book is a literary device Orwell uses to connect the past to the present of 1984.[2] Orwell may have intended Goldstein's book to parody Trotsky's (on whom Goldstein is based) 1941 The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and Where is it Going?.[3][4]

Oceania

Oceania was founded following an anti-capitalist revolution,[5] which while intended to be for the ultimate liberation of its proletariat, soon ignored them.[6] There is, however, no indication in the text to suggest how the Party obtained the power it posesses or when it did so.[7] Geographically, the state includes the Americas, Australasia, Britain and part of South Africa.[8] Oceania's political system, Ingsoc (English socialism)[9] uses cult of personality to venerate the ruler, Big Brother while the Inner Party exercises day-to-day power.[10] A system of food rationing—which did not affect Inner Party members—is in place. This is intended to both strengthen the party's control over its citizens and help them with its wars.[11] Winston considers the geography as it now stood: "even the names of countries, and their shapes on the map, had been different. Airstrip One, for instance, had not been so called in those days: it had been called England, or Britain, though London, he felt fairly certain, had always been called London.[12] There is countryside outside of London, but this is not a place for enjoying the contrast with the city but purely practical grounds of exercise.[13]

Oceania is composed of provinces, of which Airstrip One—as Britain is now called—is one. The whole province is "miserable and run-down",[9] with London consisting, almost solely, of "decaying suburbs".[14] Airstrip One is the third most populous province in Oceania, although London is not the capital; Oceania has none. This decentralisation enables the Party to ensure that each province of Oceania feels that itself is the centre of affairs, and prevents them from feeling colonised, as there is no distant capital to focus discontent on.[15] 85% of Oceania's population is Prole, with the remainder being of the Outer Party, except for a tiny number who, as members of the Inner Party, effectively rule. Although Winston yearns for revolution, and a return to a time before Oceania, says Carr, he eventually realises that "no revolution is possible in Oceania. History, in Hegelian terms, has ended. There will be no political transformations in Oceania; political change has ended because Big Brother will not let it happen". No political collapse is possible in Oceania, suggests Carr, because the government will not allow it, regardless of internal or external pressures.[16]

Although a totalitarian and highly formalised state, Oceania also has no law,[17] "only crimes" says Lynskey.[7] But although nothing is illegal, social pressure is used to exert control in place of law.[18] This makes it difficult for its citizens to know when they are in breach of the Party's expectations, which results in a state of permanent anxiety for citizens, and encourages them to be "unable to think too deeply on any subject whatsoever" so as to avoid "thoughtcrime." For example, Winston begins writing a diary. He does not know that this is a forbidden offence, but is "reasonably" certain of it.[17] In Oceania, to think is to do, and no distinction is drawn between either.[7] Likewise, although criticism of the state is forbidden—through unthink, for example—criticism must be constant for the state's survival: it must have critics to destroy to demonstrate the state's power.[19] Governance of Oceania is predicated upon the necessity of suppressing freedom of thought or original thinking among the Outer Party (the Proles are exempted from this as they are deemed incapable of having ideas).[20]

The state is also a highly bureaucratised one; as Winston notes at one point, a myriad of committees were responsible for administration, but which were "liable to hold up even the mending of a window-pane for two years".[19] The rulers of Oceania, the Inner Party, says Winston, were the intelligentsia, the "bureaucrats, scientists, technicians, trade-union organizers, publicity experts, sociologists, teachers, journalists, and professional politicians".[21] The state's national anthem is Oceania, 'Tis for Thee.[7]

Eurasia and Eastasia

Eastasia consists of China, Japan, Tibet and some Manchurian/Mongolian regions, while Eurasia comprises Russia and mainland Europe, stretching, says Winston, "from Portugal to the Bering Strait".[8] The ideology of Eurasia is Neo-Bolshevism, while that of Eastasia is called Death-Worship.[5] Like Oceania, the other two states' populations are also primarily populated by Proles.[22] Winston appears to recognise the similarities with the other superstates, at one point commenting that "it was curious to think that the sky was the same for everybody, In Eurasia or Eastasia as well as here. And the people under the sky were very much the same."[23]

International relations

The three states have been at war with each other since the 1960s.[8] By 1984 it has become a constant, although they regularly change allegiance with each other.[10] Because each state is self-supporting, they do not war over natural resources, nor is the destruction of their opponent the primary objective.[24] Indeed, even when two states ally against the third, no combination is powerful enough to do so.[25] War is necessary in order to use up the oversupply that is constantly generated by their respective extreme forms of capitalism.[11] Each state recognises that science is responsible for its over-production,[26] and as such science must be carefully controlled lest it suggest the possibility of an increased standard in living conditions to the proles or Outer Party.[27] From this analysis stems the policy of permanent warfare: by focusing production on arms and material (rather than consumer goods) each state can keep its population impoverished and willing to sacrifice personal liberties for the greater good.[8] The peoples of these states, says Carr, "is no longer domesticated or even able to be domesticated";[28] rather, they are subject to shortages, queues, poor infrastructure and food.[29]

Although they have superficially discrete ideologies, these are all, in effect, the same totalitarianism[11] and similar monolithic regimes.[9] Historian Mark Connelly notes that "the beliefs may differ, but their purpose is the same, to justify and maintain the unquestioned leadership of a totalitarian elite".[8] Each uses artificially-induced hatred of its then-enemy by its citizenry to control them.[11] Due to the sheer size of the protagonists, there are, says Connelly, no "massive invasions claiming hundreds of thousands of lives",[24] but instead small-scale, local encounters and conflicts which are then exaggerated for the purposes of domestic propaganda.[9] Connely describes the fighting between the states as "highly technical, involving small units of highly trained individuals waging battles in remote contested regions".[24] All sides once possessed nuclear weapons, but, following a short-lived resort to them in the 1950s (in which Colchester was hit)[30] they were recognised as too dangerous for any of them to use. As a result, says Connelly, although London could have been destroyed by a nuclear weapon in 1984, it was never hit by anything worse–albeit "20 or 30 times a week"–than "rocketbombs", themselves no more powerful than the V-1s or V-2s of World War Two.[24]

At any moment, however, an alliance could shift and the two states that had previously been at war with each other may suddenly ally against the other. When this happened, the past immediately had to be re-written—newspapers retyped, new photos glued over old—to provide continuity. In many cases that which contradicted the state was simply destroyed.[31] This occurs during Oceania's Hate Week, when it is announced that the state is at war with Eastasia and allied to Eurasia, despite the assembled crowd—including Winston and Julia—having just witnessed the executions of Eurasian prisoners of war. Winston describes how, when the announcer spoke, "nothing altered in his voice or manner or in the content of what he was saying, but suddenly the names were different".[32] Orwell describes the war as one of "limited aims between combatants who are unable to destroy one another, have no material cause for fighting and are not divided by any genuine ideological difference".[22] These wars, suggests the writer Roberta Kalechofsky, "stimulate the news or 'the truth'".[33]

Analysis

The superstates of Nineteen Eighty-Four are recognisably based in the world Orwell and his contemporaries knew while being distorted into a dystopia.[10] Oceania for example, argues the critic Alok Rai, "is a known country", because, while a totalitarian regime set in an alternate reality, that reality is still recognisable to the reader. The state of Oceania comprises concepts, phrases and attitudes that have been recycled—"endlessly drawn upon"—ever since the book was published.[19] They are the product, says Fabio Parascoli, of "humankind's foolishness and lack of vision".[11] They are also though, argues the critic Craig L. Carr, places where "things have gone horribly and irreparably wrong".[34]

Each state is self-supporting and self-enclosed: emigration and immigration are forbidden, as are international trade[35] and the learning of foreign languages.[36] Winston suspects, also, that the war exists for the Party's sake, and questions if it is taking place at all, and that the bombs which daily fell on London could have been launched by the Party itself "just to keep people frightened", he considers.[37]

The reader is told, through Winston, that the world has not always been this way, and indeed, once was much better;[10] on one occasion with Julia, she produces a bar of old-fashioned chocolate—what the Party issued tasted "like the smoke from a rubbish fire"—and it brought back childhood memories from before Oceania's creation.[38]

Craig Carr argues that, in creating Oceania and the other warring states, Orwell was not predicting the future, but warning of a possible future if things carried on as they did. In other words, it was also something which could be avoided. Carr continues

It is altogether easy to pick up Nineteen Eighty-Four today, notice that the year that has come to symbolize the story is now long past, realize that Oceania is not with us, and answer Orwell's warning triumphantly by saying, 'We didn't!' It is easy, in other words, to suppose that the threat Orwell imagined and the political danger he foresaw have passed.[39]

Contemporary interpretations

Economist Christopher Dent has argued that Orwell's vision of Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia "turned out to be only partially true. Many of the post-war totalitarian states have toppled, but a tripolar division of global economic and political power is certainly apparent". This is divided, he suggests, between Europe, the United States and Japan.[40] Scholar Christopher Behrends, meanwhile, has commented that the proliferation of US airbases in Britain in the 1980s echoes Orwell's classification of the country as an airbase into the European theatre.[35] The growth of supra-state organisation such as the Organisation of American States, argues the legal scholar Wolfgang Friedmann, "corresponding to the super-states of Orwell's 1984... change would be from the power balances of numerous big and small national states to the more massive and potentially more destructive balance of power between two or three blocks of super-Powers".[41] Similarly, in 2007 the UK's House of Commons' European Scrutiny Committee argued that the European Commission's stated aim to make Europe a "World Partner" should be taken to read "Europe as a World Power!", and likened it to Orwell's Eurasia. The committee also suggested that the germ of Orwell's superstates could already be found in organisations such as, not only the EU, but the ASEAN and FTAA. Further, the committee suggested that the long wars then being waged by American forces against enemies they helped originally create, such as in Baluchistan were also signs of a germinal 1984-style superstate.[42] Lynskey writes how, in 1949, as Orwell was ill but Nineteen Eighty-Four complete, "the post-war order took shape. In April, a dozen Western nations formed NATO. In August, Russia successfully detonated its first atom bomb in the Kazakh steppe. In October, Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China ...Oceania, Eurasia, Eastasia."[7]

The investigations in post-war America into domestic communism, known as McCarthyism, have been compared to the process by which the states of Nineteen Eighty-Four re-write their history in a process that the political philosopher Joseph Gabel labelled "time mastery".[31] Similarly, Winston and Julia's attempts to contact, and await contact by, members of the secret organisation called the Brotherhood have been compared to the political strategy of Kremlinology whereby Western powers study minute changes in Russian government in an attempt to foresee events.[26] The states' permanent low-level war is similar, says scholar Ian Slater that in Vietnam, except in Orwell's imagination the war is never-ending.[43] Oceania, suggests Rai, in its labyrinthine bureaucracy, was comparable to the post-war Labour government, which found itself in control of what he terms the "extensive apparatus of economic direction and control" that had been set up at the beginning of the Second World War to regulate supply. London, too, as described by Winston is a perfect match, according to Rai, for the post-war city: [19]

He tried to squeeze out some childhood memory that should tell him whether London had always been quite like this. Were there always these vistas of rotting nineteenth-century houses, their sides shored up with baulks of timber, their windows patched with cardboard and their roofs with corrugated iron, their crazy garden walls sagging in all directions? And the bombed sites where the plaster dust swirled in the air and the willow-herb straggled over the heaps of rubble; and the places where the bombs had cleared a larger patch and there had sprung up sordid colonies of wooden dwellings like chicken-houses.[44]

In a review of the book in 1950 Symons notes that the gritty, uncomfortable world of Oceania was directly relatable to by Orwell's readers: the food, milkless tea and harsh alcohol were the staples of wartime rationing, which in many cases had continued after the war.[45] Critic Irving Howe argues that, since then, other events and countries[46]—North Korea, for example[47]—have demonstrated how close Oceania can be.[46] Oceania is, he suggests, "both unreal and inescapable, a creation based on what we know, but not quite recognisable".[48] Lynskey suggests that Oceania's anthem, Oceania, Tis For Thee, is a direct reference to the United States (from "America (My Country, 'Tis of Thee)"), as also, he posits, the use of the dollar sign as the Oceanian currency denominator.[7]

Influences

The totalitarian states of Nineteen Eighty-Four, although imaginary, were based partly on the real-life regimes of Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Russia. Both regimes used techniques and tactics that Orwell later utilised in his novel: the re-writing of history, the cult of leadership personality, purges and show trials, for example. The author Czesław Miłosz commented that, in his depictions of Oceanian society, "even those who know Orwell only by hearsay are amazed that a writer who has never lived in Russia should have so keen a perception of Russian life".[19] From a purely literary standpoint, suggests Julian Symons the superstates of 1984 represent points along a path that also took Orwell from Burma to Catalonia, Spain, and Wigan in England. In each location, argues Symonds, characters are similarly confined a "tightly controlled, taboo-ridden" society, and are as suffocated by them as Winston is in Airstrip One.[19] In The Road to Wigan Pier, for example, Orwell examines working-class life in detail; the scene in 1984, where Winson observes a Prole woman hanging out her washing echoes the earlier book, where Orwell watches a woman, in the back area of a slum dwelling, attempting to clear a drain pipe with a stick.[47]

Orwell's own wartime role in the Ministry of Information saw him, says Rai, "experience at first hand the official manipulation of the flow of information, ironically, in the service of 'democracy' against 'totalitarianism'". He noted privately at the time that he could see totalitarian possibilities for the BBC that he would later provide for Oceana.[19] Similarly, argues Lynskey, during the war Orwell had had to make pro-Soviet broadcasts, lauding Britain's ally. After the war—but with a cold one looming—this became an image that needed swiftly to be discarded, and is, comments Lynskey, the historical origin of Oceania's bouleversement in its alliance during Hate Week.[7]

Comparisons

The superstates of Nineteen Eighty-Four have been compared by literary scholars to other dystopian societies such as those created by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World, Yevgeny Zamyatin's We, Franz Kafka's The Trial [49] B. F. Skinner's Walden II,[50] and Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange[51] although Orwell's bleak 1940s-style London differs fundamentally from Huxleys's world of extensive technical progression or Zamyatin's science and logic-based society.[34] Dorain Lynskey, in his The Ministry of Truth, also suggests that "equality and scientific progress, so crucial to We, have no place in Orwell's static, hierarchical dictatorship; organised deceit, so fundamental to Nineteen Eighty-Four, did not preoccupy Zamyatin".[7]

Sources

- Orwell, G. (2013). Nineteen Eighty Four. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin. p. 191. ISBN 978-0141391700.

- Slater, Ian (2003). Orwell. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 243. ISBN 0-7735-2622-6.

- Decker, James M. (2009). "George Orwell's 1984 and Political Ideology". In Bloom, Harold (ed.). George Orwell, Updated Edition. Infobase Publishing. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-4381-1300-5.

- Freedman, Carl (2002). The Incomplete Projects: Marxism, Modernity, and the Politics of Culture. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-8195-6555-6.

- Murat Kalelioğlu (3 January 2019). A Literary Semiotics Approach to the Semantic Universe of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-1-5275-2405-7.

- Kalechofsky, R. (1973). George Orwell. New York: F. Ungar. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8044-2480-6.

- Lynskey, D. (2019). The Ministry of Truth: A Biography of George Orwell's 1984. London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-5098-9076-7.

- Mark Connelly (26 October 2018). George Orwell: A Literary Companion. McFarland. pp. 140–. ISBN 978-1-4766-6677-8.

- Ashe, Geoffrey (June 28, 2001). "Encyclopedia of Prophecy". ABC-CLIO – via Google Books.

- Brackett, Virginia; Gaydosik, Victoria (April 22, 2015). "Encyclopedia of the British Novel". Infobase Learning – via Google Books.

- Parasecoli, Fabio (September 1, 2008). "Bite Me: Food in Popular Culture". Berg – via Google Books.

- Orwell, G. (2013). Nineteen Eighty Four. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin. p. 18. ISBN 978-0141391700.

- Irving Howe (1977). 1984 Revisited: Totalitarianism in Our Century. New York: Harper & Row. p. 31. ISBN 0-06-080660-5.

- Gabel, Joseph (January 1, 1997). "Ideologies and the Corruption of Thought". Transaction Publishers – via Google Books.

- Murat Kalelioğlu (3 January 2019). A Literary Semiotics Approach to the Semantic Universe of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-1-5275-2405-7.

- Craig L. Carr (2010). Orwell, Politics, and Power. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4411-0982-8.

- Slater, Ian (September 26, 2003). "Orwell: The Road to Airstrip One". McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP – via Google Books.

- Kalechofsky, R. (1973). George Orwell. New York: F. Ungar. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8044-2480-6.

- Rai, Alok (August 31, 1990). "Orwell and the Politics of Despair: A Critical Study of the Writings of George Orwell". CUP Archive – via Google Books.

- Kalechofsky, R. (1973). George Orwell. New York: F. Ungar. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-8044-2480-6.

- Irving Howe (1977). 1984 Revisited: Totalitarianism in Our Century. New York: Harper & Row. p. 198. ISBN 0-06-080660-5.

- Murat Kalelioğlu (3 January 2019). A Literary Semiotics Approach to the Semantic Universe of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-5275-2405-7.

- Irving Howe (1977). 1984 Revisited: Totalitarianism in Our Century. New York: Harper & Row. p. 32. ISBN 0-06-080660-5.

- Mark Connelly (26 October 2018). George Orwell: A Literary Companion. McFarland. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-4766-6677-8.

- Mark Connelly (26 October 2018). George Orwell: A Literary Companion. McFarland. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-4766-6677-8.

- Slater, Ian (September 26, 2003). "Orwell: The Road to Airstrip One". McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP – via Google Books.

- Slater, Ian (September 26, 2003). "Orwell: The Road to Airstrip One". McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP – via Google Books.

- Craig L. Carr (2010). Orwell, Politics, and Power. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4411-0982-8.

- Kalechofsky, R. (1973). George Orwell. New York: F. Ungar. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-8044-2480-6.

- Mark Connelly (26 October 2018). George Orwell: A Literary Companion. McFarland. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4766-6677-8.

- Gabel, Joseph (January 1, 1997). "Ideologies and the Corruption of Thought". Transaction Publishers – via Google Books.

- Slater, Ian (September 26, 2003). "Orwell: The Road to Airstrip One". McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP – via Google Books.

- Kalechofsky, R. (1973). George Orwell. New York: F. Ungar. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-8044-2480-6.

- Craig L. Carr (2010). Orwell, Politics, and Power. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4411-0982-8.

- "The Perception of George Orwell in Germany" – via books.google.co.uk.

- Irving Howe (1977). 1984 Revisited: Totalitarianism in Our Century. New York: Harper & Row. p. 30. ISBN 0-06-080660-5.

- Murat Kalelioğlu (3 January 2019). A Literary Semiotics Approach to the Semantic Universe of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-5275-2405-7.

- Parasecoli, Fabio (September 1, 2008). "Bite Me: Food in Popular Culture". Berg – via Google Books.

- Craig L. Carr (2010). Orwell, Politics, and Power. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4411-0982-8.

- Dent, Christopher M. (September 11, 2002). "The European Economy: The Global Context". Routledge – via Google Books.

- James L. Hildebrand, Complexity Analysis: A Preliminary Step Toward a General Systems Theory of International Law, 3 Ga. J. Int’l & Comp. L. 271 (1973), p.284

- House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee: The European Commission's Annual Policy Strategy 2008 (Thirty-second Report of Session 2006–07), vol. II: Oral and written evidence. Evs 28/2.5, 34/2.5.

- Slater, Ian (September 26, 2003). "Orwell: The Road to Airstrip One". McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP – via Google Books.

- Orwell, G. (2013). Nineteen Eighty Four. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin. p. 7. ISBN 978-0141391700.

- Irving Howe (1977). 1984 Revisited: Totalitarianism in Our Century. New York: Harper & Row. p. 4. ISBN 0-06-080660-5.

- Irving Howe (1977). 1984 Revisited: Totalitarianism in Our Century. New York: Harper & Row. p. 6. ISBN 0-06-080660-5.

- D.J. Taylor (2019). On Nineteen Eighty-Four: A Biography. New York: Abrams. ISBN 978-1-68335-684-4.

- Irving Howe (1977). 1984 Revisited: Totalitarianism in Our Century. New York: Harper & Row. p. 22. ISBN 0-06-080660-5.

- Susser, D., 'Hermeneutic Privacy: On Identity, Agency, and Information', (Stony Brook University PhD, 2015), p.67

- Leonard J. Eslick (1971) The Republic Revisited: The Dilemma of Liberty and Authority', World Futures: The Journal of New Paradigm Research, 10:3-4, 171-212, p.178

- Irving Howe (1977). 1984 Revisited: Totalitarianism in Our Century. New York: Harper & Row. p. 43. ISBN 0-06-080660-5.