1940 Nova Scotia hurricane

The 1940 Nova Scotia hurricane swept through areas of Atlantic Canada in mid-September 1940. The fifth tropical cyclone and fourth hurricane of the year, it formed as a tropical depression east of the Lesser Antilles on September 7, though at the time weather observations in the area were sparse, so its formation was inferred. The disturbance gradually intensified throughout much of its early formative stages, attaining tropical storm strength on September 10; further strengthening into a hurricane north of Puerto Rico occurred two days later. Shortly thereafter, the hurricane recurved northward, and reached peak intensity the following day as a Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of at least 988 mbar (hPa; 29.18 inHg). The cyclone steadily weakened thereafter before making landfall on Nova Scotia on September 17 with winds of 85 mph (135 km/h). Moving into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence later that day, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. The remnant system curved eastward and passed over Newfoundland before dissipating over the Atlantic on September 19.

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

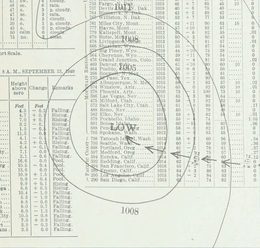

Surface weather analysis of the storm on September 13, at peak intensity | |

| Formed | September 7, 1940 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 17, 1940 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 100 mph (160 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | ≤ 988 mbar (hPa); 29.18 inHg |

| Fatalities | 3 |

| Damage | $1.49 million (1940 USD) |

| Areas affected | New England, Atlantic Canada |

| Part of the 1940 Atlantic hurricane season | |

While off the United States East Coast, the hurricane caused numerous shipping incidents, most notably the stranding of the Swedish freighter Laponia off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina on September 16. Two other boat incidents resulted in two deaths. The hurricane also brought strong winds of tropical storm-force and snow over areas of New England. In Atlantic Canada, a strong storm surge peaking at 4 ft (1.3 m) above average sunk or damaged several ships and inundated cities. In New Brunswick, the waves hurt the lobster fishing industry. In Nova Scotia, strong winds disrupted telecommunication and power services. The winds also severely damaged crops. Roughly half of apple production in Annapolis Valley was lost during the storm, resulting in around $1.49 million in economic losses.[nb 1] Strong winds in New Brunswick caused moderate to severe infrastructural damage, and additional damages to crops occurred there. Overall, the hurricane caused three fatalities, with two off the United States and one in New Brunswick.

Meteorological history

The origins of the system can be traced to a tropical depression roughly midway between the Lesser Antilles and the west coast of Africa at 1800 UTC on September 7.[1] Though initially believed to have developed on September 11,[2] the disturbance was found to have formed earlier in post-season reanalysis, based on data from the International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set.[3] In its early developmental stages, the disturbance remained a tropical depression with little change in intensity. At 0600 UTC on September 10, it intensified into a tropical storm while still east of the Lesser Antilles.[1] Closer to the islands, ships reported a quickly intensifying tropical cyclone with low barometric pressures, strong winds and heavy thunderstorms, although most of the activity occurred to the east of its center.[2][3]

At 1800 UTC on September 12, the storm intensified into the equivalent of a modern-day Category 1 hurricane to the north of Puerto Rico.[1] The following day, the hurricane began to recurve northward, attaining Category 2 intensity at 1200 UTC.[2][1] Numerous vessels in its vicinity reported hurricane-force winds; the S.S. Borinquen observed a minimum peripheral pressure of 988 mbar (hPa; 29.18 inHg), the lowest observed pressure associated with the hurricane.[2][3] At the time, the storm had maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), which it maintained throughout its duration as a Category 2 system. Progressing rapidly into more northerly latitudes, the storm weakened to a Category 1 hurricane by 1800 UTC on September 15.[1] By the next day, two warm fronts began extending eastward from the cyclone as the wind field expanded in size, indicating the start of an extratropical transition. At 0200 UTC, the hurricane made landfall near Lockeport, Nova Scotia, with winds of 85 mph (135 km/h).[3][1][4] The storm fully transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by 1200 UTC on September 17.[1] In the gulf, the system turned eastward, causing it to move ashore Newfoundland just north of Cape Race during the evening of September 18.[2] After passing over the island, the extratropical storm reentered the Atlantic Ocean, where it gradually weakened before dissipating on September 19.[1]

Preparations and impact

_at_anchor_c1943.jpg)

Offshore United States

Though initially perceived to be a potential threat to The Bahamas and Florida due to its westward motion, the hurricane curved northward on September 13, mitigating any evacuation procedures.[5] Despite the storm's change in track, the United States Weather Bureau cautioned shipping interests in the outlying islands of the Bahamas.[6] Pan American World Airways was forced to postpone two transatlantic flights from New York City to Portugal due to the storm.[7][8] After the hurricane recurved, the Weather Bureau advised caution to areas of the New England coast, particularly in Nantucket and Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where strong winds and waves were anticipated.[7] Storm warnings were posted for coastal areas from Hatteras, North Carolina to Eastport, Maine on September 16. The warnings were discontinued after the hurricane passed the warned areas.[8]

On September 16, strong waves produced by the hurricane disabled the Swedish freighter Laponia, which at the time was located 300 mi (480 km) east of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. The ship was initially en route for Rio de Janeiro carrying cargo for the Bethlehem Steel Company. As a result of the stranded ship, the SS President Roosevelt was forced to divert its course in order to render aid. The United States Coast Guard cutters USCGC Sebago (WHEC-42) and USCGC Carrabasset (WAT-55) were sent from the Virginia Capes in order to provide assistance. In addition, a coast guard plane was dispatched from Elizabeth City, North Carolina.[7] The ships remained on standby to monitor the Laponia for three hours before conditions were considered safe to tow the stricken ship back to shore.[9] Two fishing vessels capsized off Barnegat, New Jersey and Edgemere, New York, with both incidents resulting in a fatality.[7] A cabin cruiser was sent to rescue occupants of the capsized boat off Edgemere, though it was also disrupted by rough seas. The ship was later able to rescue the other surviving crew members. Numerous other small craft off Long Island signaled distress calls to the US Coast Guard due to strong waves offshore.[8] Eventually passing east of New England, the storm's large size resulted in heavy rainfall near Nantucket Island, Massachusetts.[2] A weather station on the island reported maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (70 km/h). In Eastport, Maine, a weather station recorded a minimum barometric pressure of 993 mbar (hPa; 29.33 inHg) and wind speeds of 33 mph (53 km/h).[3] In Maine, power lines were downed, damaging communications. In Bar Harbor, strong winds caused five fires, which were later extinguished. The schooner George Dresser ran aground on the port's coast. The hurricane also produced slight snowfalls in northern areas of the state.[10][11]

Nova Scotia

Most of the hurricane's damage occurred in Nova Scotia, where the storm made landfall early on September 17.[1][3] As was the case off the United States East Coast, rough seas generated by the hurricane caused various ship incidents. Tides were 4 ft (1.3 m) above average. The abnormally high sea level inundated areas of Lockeport, isolating it from the rest of Nova Scotia and creating a temporary island in the process. One home in the city was flooded by the waves. Off Shelburne, a breakwater was destroyed by rough seas. In Halifax, two yachts were damaged. Another boat in East Ferry was destroyed. The strong waves grounded a schooner in Bridgewater, damaging a wharf. In Jordan Bay, two boat houses and a barn were toppled, while a wharf was washed away.[4] Further north near Anticosti Island, the British steamer Incemore became stranded.[10] Though not directly a result of the storm surge, ten boats in Lake Milo near Yarmouth were severely damaged.

Strong winds were also felt throughout Nova Scotia. Winds peaked at 70 mph (115 km/h) in Lockeport, the strongest winds observed in the Canadian province. In Yarmouth, the storm's gusts were clocked at 60 mph (100 km/h) in Yarmouth. Trees were uprooted as a result of the strong winds. One tree fell into a home in Melville Cove, damaging the home's roof. Cabins were damaged in Summerville, and the garage of a lodge in Digby was blown out. A barn and associated equipment were destroyed in Pembroke. The strong winds also blew down numerous communication lines, disrupting telecommunication services across Nova Scotia. Downed wires in Halifax caused a fire which scorched five buildings.[4] Traffic in the city was also disrupted by the winds.[12] In addition to infrastructure, crops were also heavily damaged. In Digby County, grain and corn plantations were damaged. Grain crops in Cumberland County also saw heavy losses. In Annapolis Valley, an important agricultural region in western Nova Scotia, 600,000 barrels of apples were lost, resulting in CA$1.5 million in damages.[4] The lost apple production accounted for roughly half of the entire apple yield for the agricultural region.[10] Despite the hurricane's rapid movement through the Canadian Maritimes, the storm still produced heavy rainfall. In Halifax, 3 in (75 mm) of rain was reported over the duration of the hurricane. However, 3.5 in (90 mm) of rain fell in Yarmouth in a 24-hour period.[4]

New Brunswick

Damage from the hurricane was comparatively less in New Brunswick than in Nova Scotia, but was still considerable. The rough seas impacted ships offshore the province, disrupting the lobster industry. Two groups of lobster fishermen went missing in the Northumberland Strait; they were later found. Thousands of lobster traps and several wharves were either damaged or destroyed in the strait.[4] Hundreds of boats were set adrift or sunk in the strait as well.[3] Several boats in Rothesay and Westfield were also lost. A man in Dixon Point lost CA$1,000 of live lobsters due to the storm. A wharf in Shediac was washed away. Fifty boats were sunk off Cap-Pelé, while in Greville, four scows were destroyed. The rising seawater inundated a bridge crossing the Millstream River under 3 ft (0.9 m) of water. A bridge crossing the Little River and another bridge in Cocagne were also damaged. Dykes in the Baie Verte area were damaged, resulting in thousands of dollars in damages.[4] Further inland, winds caused infrastructural and agricultural damage. Winds peaked at 85 mph (135 km/h) at Lakeburn Airport.[4] The strong winds disrupted power and telecommunication services in Moncton. Streets were blocked by trees blown down by strong winds. Offshore, three yachts were destroyed.[10] A tree fell onto the Gagetown United Church as a result of the winds, causing considerable damage. Grain and apple crops were also destroyed in Gagetown.[4] In Saint John, chimneys were toppled.[4] Flying debris injured several people, and power outages also greatly affected the city.[11][12] High waves in conjunction with strong gusts scattered boats in the nearby Saint John River.[11] Tents in the Sussex Military Camp were destroyed. The hurricane's effects resulted in a car accident which injured eight people. Though no fatalities were confirmed in New Brunswick, a person went missing in Bathurst, who was later presumed dead.[4]

Notes

- All damage totals are in 1940 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Gallenne, J.H. (September 1, 1940). "Tropical Disturbances of September 1940" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 68 (9): 245–247. Bibcode:1940MWRv...68..245G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1940)068<0245:TDOS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- Landsea, Chris; Atlantic Oceanic Meteorological Laboratory; et al. (December 2012). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- Environment Canada (November 13, 2009). "1940-5". Storm Impact Summaries. Government of Canada. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- "Hurricane Veers Lessening Danger Of Striking Florida". Lewiston Evening Journal. Jacksonville, Florida. Associated Press. September 13, 1940. p. 11. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- "Hurricane Watched By Weather Bureau". The Palm Beach Post. Jacksonville, Florida. Associated Press. September 12, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- "Hurricane Hits Steamer; Rescue Ship Draws Near". The Evening Independent. New York, New York. Associated Press. September 16, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- "Gales and Abnormally High Tides". Warsaw Union. September 16, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- "Ship Rides Out Atlantic Storm". St. Petersburg Times. New York, New York. Associated Press. September 17, 1940. p. 15. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- "Hurricane Diminishes After Causing $1,000,000 Damage in Canadian Area". St. Petersburg Times. Halifax, Nova Scotia. United Press. September 18, 1940. p. 3. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- "Scores Hurt In Hurricane". Berkeley Daily Gazette. Halifax, Nova Scotia. United Press. September 17, 1940. pp. 1–2. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- "Hurricane Veers, Striking Halifax; 70-Mile Wind Lashes Big Harbor--St. John Power Off--Traffic Halted Halifax Virtually Cut Off, Hope for Prince Edward Island, Danger for U.S. Passes". New York Times. Montreal, Quebec. New York Times. September 17, 1940. Retrieved April 29, 2013.