Chess notation

Chess notations are various systems that have developed to record either the moves made in a game of chess or the position of pieces on a chessboard. The earliest systems of notation used lengthy narratives to describe each move; these gradually evolved into terser notation systems. Currently algebraic chess notation is the accepted standard and is widely used. Algebraic notation has several variations. Descriptive chess notation was used in English- and Spanish-language literature until the late 20th century, but is now obsolete. There are some special systems for international correspondence chess. Portable Game Notation is used when working with computer chess programs. Systems also exist for transmission using Morse code over telegraph or radio.

Recording moves

Some move-recording notations are designed mainly for use by human players; others are designed for use by computers.

Notation systems for humans

In recognized competitions, all players are required to record all the moves of both players in order to resolve disputes about whether a player has made an illegal move and what the position should now be. In addition, if there is a time limit rule that requires each player to complete a specified number of moves in a specified time, as there is in most serious competitions, an accurate count of the moves must be kept.[1] All chess coaches strongly recommend the recording of one's games so that one can look for improvements in one's play.[2] The algebraic and descriptive notations are also used in books about chess.

- Algebraic chess notation is more compact than descriptive chess notation, and is the most widely used method for recording the moves of a game of chess. In embryonic form it was used by Philip Stamma in the 1737 book Essai sur le jeu des echecs. It was later adopted (in long form) by the influential Handbuch des Schachspiels and became standard in German publications. It is more compact and less prone to error than the English descriptive system. Algebraic notation is the official notation of FIDE which must be used in all recognized international competition involving human players.[3] The U.S. Chess Federation prefers the use of algebraic notation but still permits descriptive notation.[4]

- Standard algebraic notation (SAN) is the notation standardized by FIDE.[5] It can be either long, short or minimal:

- Long algebraic notation (LAN) includes the starting file and rank of the piece.

- Short algebraic notation omits the starting file and rank of the piece, unless it is necessary to disambiguate the move.

- Minimal algebraic notation (MAN) is similar to short algebraic notation but omits the indicators for capture ("x"), en passant capture ("e.p."), check ("+") and checkmate ("#"). It was used by Chess Informant.[6]

- Figurine algebraic notation (FAN) is a widely used variation of standard algebraic notation that which replaces the letter that stands for a piece by its symbol, e.g., ♞c6 instead of Nc6 or ♖xg4 instead of Rxg4. Pawns are omitted as in standard algebraic notation. This enables the moves to be read independent of language. To display or print these symbols on a computer, one or more fonts with good Unicode support must be installed, and the document (web page, word processor document, etc.) must use one of these fonts.[7] For more information see Chess symbols in Unicode.

- Reversible algebraic notation (RAN) is based on LAN, but adds an additional letter for the piece that was captured, if any. The move can be reversed by moving the piece to its original square, and restoring the captured piece. For example, Rd2xBd6.[6]

- Concise reversible algebraic notation (CRAN) is like RAN, but omits the file or rank if it is not needed to disambiguate the move. For example, Rd2xB6. This notation is recommended by Gene Milener in Play Stronger Chess by Examining Chess 960: Usable Strategies for Fischer Random Chess Discovered.[6]

- Figurine concise reversible algebraic notation (FCRAN) is a form of CRAN with non-Staunton figurines, used by Gene Milener during Chess960 tournaments.

- Descriptive chess notation, English notation or English descriptive notation. Until the 1970s, at least in English-speaking countries, chess games were recorded and published using this notation. This is still used by a dwindling number of mainly older players, and by those who read old books (some of which are still important[8]).

- ICCF numeric notation. In international correspondence chess the use of algebraic notation may cause confusion, since different languages have different names for the pieces. The standard for transmitting moves in this form of chess is ICCF numeric notation.[9]

- Smith notation is a straightforward chess notation designed to be reversible and represent any move without ambiguity. The notation encodes the source square, destination square, and what piece was captured, if any.[10]

- Coordinate notation is similar to algebraic notation except that no abbreviation or symbol is used to show which piece is moving. It can do this almost without ambiguity because it always includes the square from which the piece moves as well as its destination, but promotions must be disambiguated by including the promoted piece type, such as in parentheses. It has proved hard for humans to write and read, but is used internally by some chess-related computer software.

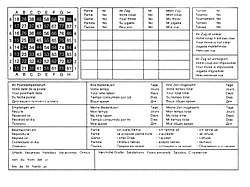

The following table lists examples of the same moves in some of the notations which may be used by humans. Each table cell contains White's move followed by Black's move, as they are listed in a single line of written notation.

| # | Algebraic | Figurine algebraic | Long algebraic | Reversible algebraic | Concise reversible | Smith | Descriptive | Coordinate | ICCF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | e4 e5 | e4 e5 | e2-e4 e7-e5 | e2-e4 e7-e5 | e24 e75 | e2e4 e7e5 | P-K4 P-K4 | E2-E4 E7-E5 | 5254 5755 |

| 2. | Nf3 Nc6 | ♘f3 ♞c6 | Ng1-f3 Nb8-c6 | Ng1-f3 Nb8-c6 | Ng1f3 Nb8c6 | g1f3 b8c6 | N-KB3 N-QB3 | G1-F3 B8-C6 | 7163 2836 |

| 3. | Bb5 a6 | ♗b5 a6 | Bf1-b5 a7-a6 | Bf1-b5 a7-a6 | Bf1b5 a76 | f1b5 a7a6 | B-N5 P-QR3 | F1-B5 A7-A6 | 6125 1716 |

| 4. | Bxc6 dxc6 | ♗xc6 dxc6 | Bb5xc6 d7xc6 | Bb5xNc6 d7xBc6 | Bb5:Nc6 d7:Bc6 | b5c6n d7c6b | BxN QPxB | B5-C6 D7-C6 | 2536 4736 |

| 5. | d3 Bb4+ | d3 ♝b4+ | d2-d3 Bf8-b4+ | d2-d3 Bf8-b4+ | d23 Bf8b4+ | d2d3 f8b4 | P-Q3 B-N5ch | D2-D3 F8-B4 | 4243 6824 |

| 6. | Nc3 Nf6 | ♘c3 ♞f6 | Nb1-c3 Ng8-f6 | Nb1-c3 Ng8-f6 | Nb1c3 Ng8f6 | b1c3 g8f6 | N-B3 N-B3 | B1-C3 G8-F6 | 2133 7866 |

| 7. | 0-0 Bxc3 | 0-0 ♝xc3 | 0-0 Bb4xc3 | 0-0 Bb4xNc3 | 0-0 Bb4:Nc3 | e1g1c b4c3n | 0-0 BxN | E1-G1 B4-C3 | 5171 2433 |

In all forms of notation, the result is usually indicated at the conclusion of the game by either "1–0", indicating that White won, "0–1" indicating that Black won or "½–½", indicating a draw. Moves that result in checkmate can be marked with "#", "++", or "‡" or to indicate the end of game and the winner, instead of or in addition to "1–0" or "0–1".

Annotators commenting on a game frequently use question marks ("?") and exclamation marks ("!") to label a move as bad or praise the move as a good one (see Chess annotation symbols).[11]

Notation systems for computers

The following are commonly used for chess-related computer systems (in addition to Coordinate and Smith notation, which are described above):

- Portable Game Notation (PGN). This is the most common of several notations that have emerged based upon algebraic chess notation, for recording chess games in a format suitable for computer processing.[12]

- Steno-Chess. This is another format suitable for computer processing. It sacrifices the ability to play through games (by a human) for conciseness, which minimises the number of characters required to store a game.[13]

- Forsyth–Edwards Notation (FEN). A single line format which gives the current positions of pieces on a board, to enable generation of a board in something other than the initial array of pieces. It also contains other information such as castling rights, move number, and color on move. It is incorporated into the PGN standard as a Tag Pair in conjunction with the SetUp tag.

- Extended Position Description (EPD). Another format which gives the current positions of a board, with an extended set of structured attribute values using the ASCII character set. It is intended for data and command interchange among chessplaying programs. It is also intended for the representation of portable opening library repositories.[14] It is better than FEN for certain chess variants, such as Chess960.

Notation for telegraph and radio

Some special methods of notation were used for transmitting moves by telegraph or radio, usually using Morse Code. The Uedemann code and Gringmuth notation worked by using a two-letter label for each square and transmitting four letters – two letters for the origin square followed by two letters for the destination square. Castling is shown as a king move. Squares are designated from White's side of the board, files from left to right and ranks from nearest to farthest. The Rutherford code first converted the move into a number and then converted the move number into a composite Latin word. It could also transmit moves of two games at the same time.

Uedemann code

This code was devised by Louis Uedemann (1854–1912). The method was never actually used, mainly because a transposition of letters can result in a valid but incorrect move. Many sources incorrectly use this name for the Gringmuth code.

The files are labeled "A", "E", "I", "O", "O", "I", "E", and "A". The ranks are labeled "B", "D", "F", "G", "H", "K", "L", and "P". A square on the queenside is designated by its file letter and then its rank letter. A square on the kingside is designated by its rank letter then its file letter.[15]

Gringmuth notation

This method was invented by Dmitry Alexeyevich Gringmuth but it is sometimes incorrectly called the Uedemann Code. It was used as early as 1866. Files were designated with one of two letters, depending on whether it was on White's side or Black's side. These letters were: B and M, C and N, D and P, F and R, G and S, H and T, K and W, L and Z. Ranks were labeled: "A", "E", "I", "O", "O", "I", "E", and "A".[15]

Rutherford code

This code was invented in 1880 by Sir William Watson Rutherford (1853–1927). At the time, the British Post Office did not allow digits or ciphers in telegrams, but they did allow Latin words. This method also allowed moves for two games to be transmitted at the same time. In this method, the legal moves in the position were counted using a system until the move being made was reached. This was done for both games. The move number of the first game was multiplied by 60 and added to the move number of the second game. Leading zeros were added as necessary to give a four-digit number. The first two digits would be 00 through 39, which corresponded to a table of 40 Latin roots. The third digit corresponded to a list of 10 Latin prefixes and the last digit corresponded to a list of 10 Latin suffixes. The resulting word was transmitted.

After rules were changed so that ciphers were allowed in telegrams, this system was replaced by the Gringmuth Notation.[15]

Recording positions

Positions are usually shown as diagrams (images), using the symbols shown here for the pieces.

There is also a notation for recording positions in text format, called the Forsyth–Edwards notation (FEN). This is useful for adjourning a game to resume later or for conveying chess problem positions without a diagram. A position can also be recorded by listing the pieces and the squares they reside on, for example: White: Ke1, Rd3, etc.

Written chess notation recording is often necessary when participating in chess tournaments. In many tournaments players are required to record their games' notation on a score sheet.[16]

Endgame classification

There are also systems for classifying types of endgames. See Chess endgame#Endgame classification for more details.

History

The notation for chess moves evolved slowly, as these examples show. The last is in algebraic chess notation; the others show the evolution of descriptive chess notation and use spelling and notation of the period.

- 1614: The white king commands his owne knight into the third house before his owne bishop.

- 1750: K. knight to His Bishop's 3d.

- 1837: K.Kt. to B.third sq.

- 1848: K.Kt. to B's 3rd.

- 1859: K. Kt. to B. 3d.

- 1874: K Kt to B3

- 1889: KKt-B3

- 1904: Kt-KB3

- 1946: N-KB3

- Modern: Nf3[17]

A text from Shakespeare's time uses complete sentences to describe moves, for example, "Then the black king for his second draught brings forth his queene, and placest her in the third house, in front of his bishop's pawne", which we would now write as 2... Qf6.[18] The great 18th-century player Philidor used an almost equally verbose approach in his influential book "Analyse du jeu des Échecs", for example, "The king's bishop, at his queen bishop's fourth square."[19]

Algebraic chess notation was first used by Philipp Stamma (c. 1705–1755) in an almost fully developed form before the now obsolete descriptive chess notation evolved. The main difference between Stamma's system and the modern system is that Stamma used "p" for pawn moves and the original file of the piece ("a" through "h") instead of the initial letter of the piece.[20] In London in 1747, Philidor convincingly defeated Stamma in a match. Consequently, his writings (which were translated into English) became more influential than Stamma's in the English-speaking chess world; this may have led to the adoption of a descriptive system for writing chess moves, rather than Stamma's coordinate-based approach. However, algebraic notation became popular in Europe following its adoption by the highly influential Handbuch des Schachspiels, and became dominant in Europe during the 20th century. However, it did not become popular in the English-speaking countries until the 1970s.[21]

See also

| The Wikibook Chess has a page on the topic of: Notating The Game |

References

- Gijssen, G. "An Arbiter's Notebook". ChessCafé.com. Archived from the original on 2007-11-05.

- "How to Read and Write Algebraic Chess Notation". The Chess House. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Includes sample hand-written score sheet.

- Schiller, Eric, The Official Rules of Chess, 2003, ISBN 978-1-58042-092-1, p. 25

- "Rulebook Changes (as of August 2007)". The United States Chess Federation. Archived from the original on 2015-06-10.

- "FIDE Handbook: Rules - Appendices". Fédération Internationale des Échecs. Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- Jeffreys, Michael. "Not Your Father's Chess". Archived from the original on 22 June 2006. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- "Test for Unicode support in Web browsers". Archived from the original on 2008-01-03.

- McKim, D.K. "Great Chess Books". Jeremy Silman. Archived from the original on 2007-12-19. Published by an International Master and prolific writer.

- "ICCF Numeric Chess Notation". ChessNotation.com. Archived from the original on 2017-01-05.

- "Chess Viewer - Smith Notation". ChessClub.com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-17.

- "Algebraic and descriptive notations". Exeter Chess Club. Archived from the original on 2007-12-23. See section "Symbols: evaluation and comment codes"

- Members of the Internet newsgroup rec.games.chess. Edwards, S.J. (ed.). "ICC Help: PGN spec". The Internet Chess Club. Archived from the original on 2004-08-07.

- Angelini, Éric. "Steno-Chess". www.chessvariants.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-08-22. Retrieved 2007-06-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld, 1992, The Oxford Companion to Chess, ISBN 0-19-280049-3

- "How to Read and Write Chess Notation". Archived from the original on 2017-04-13.

- Robert John McCrary (editor), The Hall-of-Fame History of U.S. Chess, Volume 1, pp. 14-15.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2017-06-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Saul, Arthur. The famous game of chesse-play truely discouered, and all doubts resolued; so that by reading this small booke thou shalt profit more then by the playing a thousand mates. An exercise full of delight; fit for princes, or any person of what qualitie soeuer. Published by A. S. Gent. 1614

- François-André Danican Philidor, Analysis of the Game of Chess (1777), Hardinge Simpole, 2005 (reprint), p. 2.

- Davidson, Henry (1981). "A Short History of Chess (1949)". McKay: 152–53. ISBN 0-679-14550-8. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - McCrary , R.J. "The History of Chess Notation". Archived from the original on 2008-07-04.