Draughts

Draughts (British English) or checkers[note 1] (American English) is a group of strategy board games for two players which involve diagonal moves of uniform game pieces and mandatory captures by jumping over opponent pieces. Draughts developed from alquerque.[1] The name derives from the verb to draw or to move.[2]

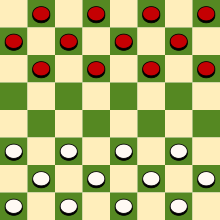

Starting position for English draughts on an 8×8 draughts board | |

| Years active | at least 5,000 |

|---|---|

| Genre(s) | Board game Abstract strategy game Mind sport |

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | <1 minute |

| Playing time | 30 minutes – 2 hours |

| Random chance | None |

| Skill(s) required | Strategy, tactics |

| Synonym(s) | Checkers Chequers |

The most popular forms are English draughts, also called American checkers, played on an 8×8 checkerboard; Russian draughts, also played on an 8×8, and international draughts, played on a 10×10 board. There are many other variants played on 8×8 boards. Canadian checkers and Singaporean/Malaysian checkers (also locally known as dum) are played on a 12×12 board.

English draughts was weakly solved in 2007 by the team of Canadian computer scientist Jonathan Schaeffer. From the standard starting position, both players can guarantee a draw with perfect play.

General rules

Draughts is played by two opponents, on opposite sides of the gameboard. One player has the dark pieces; the other has the light pieces. Players alternate turns. A player may not move an opponent's piece. A move consists of moving a piece diagonally to an adjacent unoccupied square. If the adjacent square contains an opponent's piece, and the square immediately beyond it is vacant, the piece may be captured (and removed from the game) by jumping over it.

Only the dark squares of the checkered board are used. A piece may move only diagonally into an unoccupied square. When presented, capturing is mandatory in most official rules, although some rule variations make capturing optional.[3] In almost all variants, the player without pieces remaining, or who cannot move due to being blocked, loses the game.

Men

Uncrowned pieces (men) move one step diagonally forwards, and capture an opponent's piece by moving two consecutive steps in the same line, jumping over the piece on the first step. Multiple enemy pieces can be captured in a single turn provided this is done by successive jumps made by a single piece; the jumps do not need to be in the same line and may "zigzag" (change diagonal direction). In English draughts men can jump only forwards; in international draughts and Russian draughts men can jump both forwards and backwards.

Kings

When a man reaches the kings row (also called crownhead, the farthest row forward), it becomes a king, and is marked by placing an additional piece on top of the first man (crowned), and acquires additional powers including the ability to move backwards and (in variants where they cannot already do so) capture backwards. Like men, a king can make successive jumps in a single turn provided that each jump captures an enemy man or king.

In international draughts, kings (also called flying kings) move any distance along unblocked diagonals, and may capture an opposing man any distance away by jumping to any of the unoccupied squares immediately beyond it. Because jumped pieces remain on the board until the turn is complete, it is possible to reach a position in a multi-jump move where the flying king is blocked from capturing further by a piece already jumped.

Flying kings are not used in English draughts; a king's only advantage over a man is the ability to move and capture backwards as well as forwards.

Naming

In most non-English languages (except those that acquired the game from English speakers), draughts is called dame, dames, damas, or a similar term that refers to ladies. The pieces are usually called men, stones, "peón" (pawn) or a similar term; men promoted to kings are called dames or ladies. In these languages, the queen in chess or in card games is usually called by the same term as the kings in draughts. A case in point includes the Greek terminology, in which draughts is called "ντάμα" (dama), which is also one term for the queen in chess.

National and regional variants

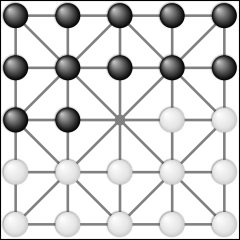

Starting position in international draughts which is played on a 10×10 board

Starting position in international draughts which is played on a 10×10 board

- Starting position in Canadian draughts

.png) Board and starting position in Turkish draughts

Board and starting position in Turkish draughts- Starting position in Italian and Portuguese draughts

A Russian column draughts game

A Russian column draughts game

Russian Column draughts

Column draughts (Russian towers) is a kind of draughts, known in Russia since the beginning of the nineteenth century, in which the game is played according to the usual rules of draughts, but with the difference that the beaten draught is not removed from the playing field, and is captured under the beating figure (draught or tower).

The resulting towers move around the board as a whole, "obeying" the upper draught. When taking the tower, only the upper draught is removed from it. If on the top there is a draught of other colour than removed as a result of fight, the tower becomes a tower of the rival. Rules of moves of draughts and kings correspond to the rules of Russian draughts.

- Russian Wikipedia article on Russian Column draughts

Flying kings; men can capture backwards

| National variant | Board size | Pieces per side | Double-corner or light square on player's near-right? | First move | Capture constraints | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International draughts (or Polish draughts) | 10×10 | 20 | Yes | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Pieces promote only when ending their move on the final rank, not when passing through it. It is mainly played in the Netherlands, Suriname, France, Belgium, some eastern European countries, some parts of Africa, some parts of the former USSR, and other European countries. |

| Ghanaian draughts (or damii) | 10×10 | 20 | No[4] | White | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. Overlooking a king's capture opportunity leads to forfeiture of the king. | Played in Ghana. Having only a single piece remaining (man or king) loses the game. |

| Frisian draughts | 10×10 | 20 | Yes | White | A sequence of capture must give the maximum "value" to the capture, and a king (called a wolf) has a value of less than two men but more than one man. If a sequence with a capturing wolf and a sequence with a capturing man have the same value, the wolf must capture. The main difference with the other games is that the captures can be made diagonally, but also straight forwards and sideways. | Played primarily in Friesland (Dutch province) historically, but in the last decade spreading rapidly over Europe (e.g. the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Czech Republic, Ukraine and Russia) and Africa, as a result of a number of recent international tournaments and the availability of an iOS and Android app "Frisian Draughts". |

| Canadian checkers | 12×12 | 30 | Yes | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | International rules on a 12×12 board. Played mainly in Canada. |

| Brazilian draughts (or derecha) | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Played in Brazil. The rules come from international draughts, but board size and number of pieces come from English draughts.

In the Philippines, it is known as derecha and is played on a mirrored board, often replaced by a crossed lined board (only diagonals are represented). |

| Pool checkers | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Also called Spanish Pool checkers. It is mainly played in the southeastern United States; traditional among African American players. A man reaching the kings row is promoted only if he does not have additional backwards jumps (as in international draughts).

In an ending with three kings versus one king, the player with three kings must win in thirteen moves or the game is a draw. |

| Jamaican draughts/checkers | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Similar to Pool checkers with the exception of the main diagonal on the right instead of the left. A man reaching the kings row is promoted only if he does not have additional backwards jumps (as in international draughts).

In an ending with three kings versus one king, the player with three kings must win in thirteen moves or the game is a draw. |

| Russian draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | White | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Also called shashki or Russian shashki checkers. It is mainly played in the former USSR and in Israel. Rules are similar to international draughts, except:

There is also a 10×8 board variant (with two additional columns labelled i and k) and the give-away variant Poddavki. There are official championships for shashki and its variants. |

| Mozambican draughts/checkers | 8×8 | 12 | No | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. Although, a king has the weight of two pieces, this means with two captures, one of a king and one of piece you must choose the king; two captures, one of a king and one of two pieces, you can choose; two captures with one of a king and one of three pieces you choose the three pieces; two captures, one of two kings and one of three pieces, you choose the kings... | Also called "Dama" or "Damas". It is played along all of the region of Mozambique. In an ending with three kings versus one king, the player with three kings must win in twelve moves or the game is a draw. |

Flying kings; men cannot capture backwards

| National variant | Board size | Pieces per side | Double-corner or light square on player's near-right? | First move | Capture constraints | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Light square is on right, but double corner is on left, as play is on the light squares. (Play on the dark squares with dark square on right is Portuguese draughts.) | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces, and the maximum possible number of kings from all such sequences. | Also called Spanish checkers. It is mainly played in Portugal, some parts of South America, and some Northern African countries. |

| Malaysian/Singaporean checkers | 12×12 | 30 | Yes | Not fixed | Captures are mandatory. Failing to capture results in forfeiture of that piece (huffing). | Mainly played in Malaysia, Singapore, and the region nearby. Also known locally as "Black–White Chess". Sometimes it is played on an 8×8 board when a 12×12 board is unavailable; a 10×10 board is rare in this region. |

| Czech draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | White | If there are sequences of captures with either a man or a king, the king must be chosen. After that, any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | This variant is from the family of the Spanish game. |

| Hungarian Highlander (Slovak) draughts | 8×8 | 8 | White | All pieces are long-range. Jumping is mandatory after first move of the rook. Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | The uppermost symbol of the cube determines its value, which is decreased after being jumped. Having only one piece remaining loses the game. | |

| Argentinian draughts | 8×8

10x10 |

12

15 |

No | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces, and the maximum possible number of kings from all such sequences. If both sequences capture the same number of pieces and one is with a king, the king must do. | The rules are similar to the Spanish game, but the king, when it captures, must stop after the captured piece, and may begin a new capture movement from there.

With this rule, there is no draw with two pieces versus one. |

| Thai draughts | 8×8 | 8 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | During a capturing move, pieces are removed immediately after capture. Kings stop on the square directly behind the piece captured and must continue capturing from there, if possible, even in the direction where they have come from. |

| German draughts (or Dame) | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Kings stop on the square directly behind the piece captured and must continue capturing from there as long as possible. |

| Turkish draughts | 8×8 | 16 | N/A | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Also known as Dama. All 64 squares are used, dark and light. Men move straight forwards or sideways, instead of diagonally. When a man reaches the last row, it is promoted to a flying king (Dama), which moves like a rook (or a queen in the Armenian variant). The pieces start on the second and third rows.

It is played in Turkey, Kuwait, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Greece, and several other locations in the Middle East, as well as in the same locations as Russian checkers. There are several variants in these countries, with the Armenian variant (called tama) allowing also forward-diagonal movement of men. |

| Myanmar draughts | 8×8 | 12 | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Players agree before starting the game between "Must Capture" or "Free Capture". In the "Must Capture" type of game, a man that fails to capture is forfeited (huffed). In the "Free Capture" game, capturing is optional. | |

| Tanzanian draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Not fixed | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Captures are mandatory. When either a king or a man can capture, there is no priority. |

No flying kings; men cannot capture backwards

| National variant | Board size | Pieces per side | Double-corner or light square on player's near-right? | First move | Capture constraints | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Also called "straight checkers" or American checkers, since it is also played in the United States. |

| Italian draughts | 8×8 | 12 | No | White | Men cannot jump kings. A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. If more than one sequence qualifies, the capture must be done with a king instead of a man. If more than one sequence qualifies, the one that captures a greater number of kings must be chosen. If there are still more sequences, the one that captures a king first must be chosen. | It is mainly played in Italy and some North African countries. |

| Gothic checkers (or Altdeutsches Damespiel or Altdeutsche Dame) | 8×8 | 16 | N/A | White | Captures are mandatory. | All 64 squares are used, dark and light. Men move one cell diagonally forward and capture in any of the five cells directly forward, diagonally forward, or sideways, but not backward. Men promote on the last row. Kings may move and attack in any of the eight directions. There is also a variant with flying kings. |

Sport

The World Championship in English draughts began in 1840. The winners in men's have been from the United Kingdom, United States, Barbados, and most recently Italy (3-Move division). The women's championship in English draughts started in 1993. The women's winners have been from Ireland, Turkmenistan, and Ukraine.

The World Championship in international draughts began in 1885 in France, and since 1948 has been organised by the World Draughts Federation (FMJD, Fédération Mondiale du Jeu de Dames). It occurs every two years. In even years following the tournament, the World Title match takes place. The men's championship has had winners from the Netherlands, Canada, the Soviet Union, Senegal, Latvia, and Russia. The first Women's World Championship was held in 1973. The World Junior Championship has been played since 1971. European Championships have been held since 1965 (men's) and 2000 (women's).

Other official World Championships began as follows: Brazilian draughts, in 1985; Russian draughts, in 1993; Turkish draughts, in 2014.

Invented variants

- Blue and Gray: On a 9×9 board, each side has 17 guard pieces that move and jump in any direction, to escort a captain piece which races to the centre of the board to win.

- Cheskers: A variant invented by Solomon Golomb. Each player begins with a bishop and a camel (which jumps with coordinates (3,1) rather than (2,1) so as to stay on the black squares), and men reaching the back rank promote to a bishop, camel, or king.

- Damath: A variant utilising math principles and numbered chips popular in the Philippines.

- Dameo: A variant played on an 8×8 board, move and capture rules are similar to those of Armenian draughts. A special "sliding" move is used for moving a line of checkers similar to the movement rule in Epaminondas. By Christian Freeling (2000).

- Hexdame: A literal adaptation of international draughts to a hexagonal gameboard. By Christian Freeling (1979).

- Lasca: A checkers variant on a 7×7 board, with 25 fields used. Jumped pieces are placed under the jumper, so that towers are built. Only the top piece of a jumped tower is captured. This variant was invented by World Chess Champion Emanuel Lasker.

- Philosophy shogi checkers: A variant on a 9×9 board, game ending with capturing opponent's king. Invented by Inoue Enryō and described in Japanese book in 1890.

- Suicide checkers (also called Anti-Checkers, Giveaway Checkers or Losing Draughts): A variant where the objective of each player is to lose all of their pieces.

- Tiers: A complex variant which allows players to upgrade their pieces beyond kings.

- Vigman's draughts: Each player has 24 pieces (two full sets) – one on the light squares, a second set on dark squares. Each player plays two games simultaneously: one on light squares, the other on dark squares. The total result is the sum of results for both games.

Games sometimes confused with draughts variants

- Halma: A game in which pieces move in any direction and jump over any other piece (but no captures), friend or enemy, and players try to move them all into an opposite corner.

- Chinese Checkers: Based on Halma, but uses a star-shaped board divided into equilateral triangles.

- Konane: "Hawaiian checkers".

History

Ancient games

Similar games have been played for a millennia.[2] A board resembling a draughts board was found in Ur dating from 3000 BC.[5] In the British Museum are specimens of ancient Egyptian checkerboards, found with their pieces in burial chambers, and the game was played by Queen Hatasu.[2][6] Plato mentioned a game, πεττεία or petteia, as being of Egyptian origin,[6] and Homer also mentions it.[6] The method of capture was placing two pieces on either side of the opponent's piece. It was said to have been played during the Trojan War.[7][8] The Romans played a derivation of petteia called latrunculi, or the game of the Little Soldiers. The pieces, and sporadically the game itself, were called calculi (pebbles).[6][9]

Alquerque

An Arabic game called Quirkat or al-qirq, with similar play to modern draughts, was played on a 5×5 board. It is mentioned in the 10th-century work Kitab al-Aghani.[5] Al qirq was also the name for the game that is now called nine men's morris.[10] Al qirq was brought to Spain by the Moors,[11] where it became known as Alquerque, the Spanish derivation of the Arabic name. The rules are given in the 13th-century book Libro de los juegos.[5] In about 1100, probably in the south of France, the game of Alquerque was adapted using backgammon pieces on a chessboard.[12] Each piece was called a "fers", the same name as the chess queen, as the move of the two pieces was the same at the time.[13]

Crowning

The rule of crowning was used by the 13th century, as it is mentioned in the Philip Mouskat's Chronique in 1243[5] when the game was known as Fierges, the name used for the chess queen (derived from the Persian ferz, meaning royal counsellor or vizier). The pieces became known as "dames" when that name was also adopted for the chess queen.[13] The rule forcing players to take whenever possible was introduced in France in around 1535, at which point the game became known as Jeu forcé, identical to modern English draughts.[5][12] The game without forced capture became known as Le jeu plaisant de dames, the precursor of international draughts.

The 18th-century English author Samuel Johnson wrote a foreword to a 1756 book about draughts by William Payne, the earliest book in English about the game.[6]

Computer draughts

English draughts (American 8×8 checkers) has been the arena for several notable advances in game artificial intelligence. In the 1950s, Arthur Samuel created one of the first board game-playing programs of any kind. More recently, in 2007 scientists at the University of Alberta[14] developed their "Chinook" program to the point where it is unbeatable. A brute force approach that took hundreds of computers working nearly two decades was used to solve the game,[15] showing that a game of draughts will always end in a draw if neither player makes a mistake.[16][17] The solution is for the draughts variation called go-as-you-please (GAYP) checkers and not for the variation called three-move restriction checkers. As of December 2007, this makes English draughts the most complex game ever solved.

Computational complexity

Generalized Checkers is played on an N × N board.

It is PSPACE-hard to determine whether a specified player has a winning strategy. And if a polynomial bound is placed on the number of moves that are allowed in between jumps (which is a reasonable generalisation of the drawing rule in standard Checkers), then the problem is in PSPACE, thus it is PSPACE-complete.[18] However, without this bound, Checkers is EXPTIME-complete.[19]

However, other problems have only polynomial complexity:[18]

- Can one player remove all the other player's pieces in one move (by several jumps)?

- Can one player king a piece in one move?

See also

Notes

- When this word is used in the UK, it is usually spelt chequers (as in Chinese chequers); see further at American and British spelling differences.

References

Citations

- Masters, James. "Draughts, Checkers - Online Guide". www.tradgames.org.uk.

- Strutt, Joseph (1801). The sports and pastimes of the people of England. London. p. 255.

- As is standard in modern Variants; see more at The Online Guide to Traditional Games

- Salm and Falola, Culture and Customs of Ghana, p. 160

- Oxland, Kevin (2004). Gameplay and design (Illustrated ed.). Pearson Education. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-321-20467-7.

- "Lure of checkers". The Ellensburgh Capital. 17 February 1916. p. 1. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Petteia". 9 December 2006. Archived from the original on 9 December 2006.

- Austin, Roland G. (September 1940). "Greek Board Games". Antiquity. University of Liverpool, England. 14: 257–271. Archived from the original on 8 April 2009. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- Peck, Harry Thurston (1898). "Latruncŭli". Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. New York: Harper and Brothers. Retrieved 23 November 2006.

- Berger, F (2004). "From circle and square to the image of the world: a possible interpretation or some petroglyphs of merels boards" (PDF). Rock Art Research. 21 (1): 11–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2004.

- Bell, R. C. (1979). Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations. I. New York City: Dover Publications. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-486-23855-5.

- Bell, Robert Charles (1981). Board and Table Game Antiques (Illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 0-85263-538-9.

- Murray, H. J. R. (1913). A History of Chess. Benjamin Press (originally published by Oxford University Press). ISBN 0-936317-01-9. OCLC 13472872.

- Chinook - World Man-Machine Checkers Champion Archived 24 June 2003 at the Wayback Machine

- Schaeffer, Jonathan; Burch, Neil; Björnsson, Yngvi; Kishimoto, Akihiro; Müller, Martin; Lake, Robert; Lu, Paul; Sutphen, Steve (14 September 2007). "Checkers Is Solved". Science. 317 (5844): 1518–1522. doi:10.1126/science.1144079. PMID 17641166.

- Jonathan Schaeffer, Yngvi Bjornsson, Neil Burch, Akihiro Kishimoto, Martin Muller, Rob Lake, Paul Lu and Steve Sutphen. Solving Checkers, International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), pp. 292-297, 2005. Distinguished Paper Prize

- "Chinook - Solving Checkers Publications". www.cs.ualberta.ca. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- Fraenkel, Aviezri S.; Garey, M. R.; Johnson, David S.; Yesha, Yaacov (1978). "The complexity of checkers on an N × N board". 19th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. p. 55. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1978.36.

- Robson, J. M. (May 1984). "N by N Checkers is EXPTIME complete". SIAM Journal on Computing. 13 (2): 252–267. doi:10.1137/0213018.

Sources

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Draughts. |

Draughts associations and federations

- American Checker Federation (ACF)

- American Pool Checkers Association (APCA)

- Danish Draughts Federation

- English Draughts Association (EDA)

- European Draughts Confederation

- German Draughts Association (DSV NRW)

- Northwest Draughts Federation (NWDF)

- Polish Draughts Federation (PDF)

- Surinam Draughts Federation (SDB)

- World Checkers & Draughts Federation

- World Draughts Federation (FMJD)

- The International Draughts Committee of the Disabled (IDCD)

History, articles, variants, rules

- A Guide to Checkers Families and Rules by Sultan Ratrout

- The history of checkers/draughts

- Jim Loy's checkers pages with many links and articles.

- Checkers Maven, CheckersUSA checkers books, electronic editions

- The Checkers Family

- Alemanni Checkers Pages

- On the evolution of Draughts variants

- “Chess and Draughts/Checkers” by Edward Winter

Online play

- mindoku.com Play online draughts, Russian draughts or giveaway draughts. Online tournaments every day.

- Server for playing correspondence tournaments

- A free program that allows you to play more than 20 kinds of draughts

- A free Application that allows you to play 15 popular checkers variants with a human or a computer

- Draughts.org Play online draughts plus information on strategies and history.

- Lidraughts.org Internet draughts server, similar to the popular chess server lichess.org