Rook (chess)

The rook (/rʊk/; ♖,♜) is a piece in the game of chess resembling a castle. Formerly the piece (from Persian رخ rokh/rukh) was called the tower, marquess, rector, and comes (Sunnucks 1970). The term castle is considered to be informal, incorrect, or old-fashioned.[1][2]

Each player starts the game with two rooks, one on each of the corner squares on their own side of the board.

Placement and movement

The white rooks start on squares a1 and h1, while the black rooks start on a8 and h8. The rook moves horizontally or vertically, through any number of unoccupied squares (see diagram). As with captures by other pieces, the rook captures by occupying the square on which the enemy piece sits. The rook also participates, with the king, in a special move called castling.

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Strategy

Relative value

In general, rooks are stronger than bishops or knights (which are called minor pieces) and are considered greater in value than either of those pieces by nearly two pawns but less valuable than two minor pieces by approximately a pawn. Two rooks are generally considered to be worth slightly more than a queen (see chess piece relative value). Winning a rook for a bishop or knight is referred to as winning the exchange. Rooks and queens are called heavy pieces or major pieces, as opposed to bishops and knights, the minor pieces.

Development

In the opening, the rooks are blocked in by other pieces and cannot immediately participate in the game, so it is usually desirable to connect one's rooks on the first rank by castling and then clearing all pieces except the king and rooks from the first rank. In that position, the rooks support each other and can more easily move to occupy and control the most favorable files.

A common strategic goal is to develop a rook on the first rank of an open file (i.e., one unobstructed by pawns of either player) or a half-open file (i.e., one unobstructed by friendly pawns). From this position, the rook is relatively unexposed to risk but can exert control on every square on the file. If one file is particularly important, a player might advance one rook on it, then position the other rook behind—doubling the rooks.

A rook on the seventh rank (the opponent's second rank) is typically very powerful, as it threatens the opponent's unadvanced pawns and hems in the enemy king. A rook on the seventh rank is often considered sufficient compensation for a pawn (Fine & Benko 2003:586). In the diagrammed position from a game between Lev Polugaevsky and Larry Evans,[3] the rook on the seventh rank enables White to draw, despite being a pawn down (Griffiths 1992:102–3).

Two rooks on the seventh rank are often enough to force victory, or at least a draw by perpetual check.[4]

Polugaevsky vs. Evans, 1970

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Chigorin vs. Steinitz, Havana 1892

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Endgame

Rooks are most powerful towards the end of a game (i.e., the endgame), when they can move unobstructed by pawns and control large numbers of squares. They are somewhat clumsy at restraining enemy pawns from advancing towards promotion, unless they can occupy the file behind the advancing pawn. As well, a rook best supports a friendly pawn towards promotion from behind it on the same file (see Tarrasch rule).

In a position with a rook and one or two minor pieces versus two rooks, generally in addition to pawns, and possibly other pieces – Lev Alburt advises that the player with the single rook should avoid exchanging the rook for one of his opponent's rooks (Alburt 2009:44).

The rook is a very powerful piece to deliver checkmate. Below are a few examples of rook checkmates that are easy to force.

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

History

In the medieval shatranj, the rook symbolized a chariot. The Persian word rukh means chariot (Davidson 1949:10), and the corresponding piece in the original Indian version chaturanga has the name ratha (meaning "chariot"). In modern times it is mostly known as हाथी (elephant) to Hindi-speaking players, while east Asian chess games such as xiangqi and shogi have names also meaning chariot (車) for the same piece.[5]

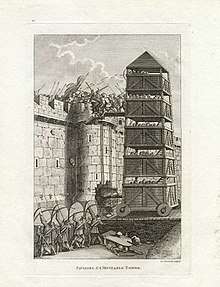

Persian war chariots were heavily armored, carrying a driver and at least one ranged-weapon bearer, such as an archer. The sides of the chariot were built to resemble fortified stone work, giving the impression of small, mobile buildings, causing terror on the battlefield.

In Europe the castle or tower appears for the first time in the 16th century in Vida’s Ludus Scacchia, and then as a tower on the back of an elephant. In time, the elephant disappeared and only the tower was used as a rook.[6]

In the West, the rook is almost universally represented as a crenellated turret. The piece is called torre ("tower") in Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish; tour in French; toren in Dutch; Turm in German; torn in Swedish; and torni in Finnish. In Hungarian it is bástya ("bastion") and in Hebrew language it is called צריח (pronounced "Tzariach", meaning "fortified tower"). In the British Museum's collection of the medieval Lewis chess pieces the rooks appear as stern warders, or wild-eyed Berserker warriors.

Rooks usually are similar in appearance to small castles, and as a result a rook is sometimes called a "castle" (Hooper & Whyld 1996). In modern chess literature this term is rarely, if ever, used.[7]

In some languages the rook is called a ship: Thai เรือ (reūa), Armenian Նավակ (navak), Russian ладья (ladya), Javanese ꦥꦫꦄꦲꦸ (prahu). This may be because of the use of an Arabic style V-shaped rook piece, which some may have mistaken for a ship.[8][9][10][11] It is possible that the rendition comes from Sanskrit roka (ship), but this was challenged by the fact that no chaturanga pieces ever called a roka. Murray argued that the Javanese could not visualize a chariot moving through the jungles in sweeping fashion as the rook. The only vehicle that moved in straight fashion was ship, thus they replaced it with prahu. Murray, however, did not give explanation about why the Russians called it a ship.[11]

In Bulgarian, it is called the cannon (Топ, Romanised top).

In Kannada, it is known as ಆನೆ (āāne), meaning "elephant".[12] This is unusual, as the term "elephant" is in many other languages applied to the bishop.[13]

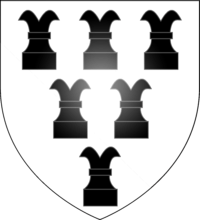

Heraldry

Chess rooks frequently occur as heraldic charges. Heraldic rooks are usually shown as they looked in medieval chess-sets, with the usual battlements replaced by two outward-curving horns. They occur in arms from around the 13th century onwards.

In Canadian heraldry, the chess rook is the cadency mark of a fifth daughter.

Unicode

Unicode defines two codepoints for rook:

♖ U+2656 White Chess Rook (HTML ♖)

♜ U+265C Black Chess Rook (HTML ♜)

See also

- Chess piece relative value

- (the) Exchange – a rook for a minor piece

- Lucena position – winning position

- Philidor position – drawing position

- Rook and pawn versus rook endgame

- Staunton chess set

- Tarrasch rule – rooks belong behind passed pawns

Notes

- Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. (online version, accessed Jan. 27, 2009), entry for "Castle", def. 9. "Chess. One of the pieces, made to represent a castle; also called a ROOK.". New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd ed. (2005) says that "castle" is informal and an "old-fashioned term for rook". The Oxford Companion to Chess, by David Hooper & Kenneth Whyld, 2nd ed. (1992), p. 344 says "In English-speaking countries non-players sometimes call it a castle...". Let's Play Chess by Bruce Pandolfini (1986) p. 30, says "The rook is the piece mistakenly called the castle."; The Everything Chess Basics Book by Peter Kurzdorfer and the United States Chess Federation, Adams Media 2003, page 30, says "... often incorrectly referred to as a castle by the uninitiated".

- The Official Rules of Chess by Eric Schiller, The US Chess Federation Official Rules of Chess (five editions by various authors), Official Chess Handbook, by Kenneth Harkness, Official Chess Rulebook by Harkness, and The Official Laws of Chess by FIDE (two editions) all use only the term "rook". Books for beginners such as Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess, A World Champion's Guide to Chess by Susan Polgar, The Complete Book of Chess by I. A. Horowitz & P. L. Rothenberg, and Chess Fundamentals by José Capablanca (2006 revision by Nick de Firmian) also only mention "rook".

- "Lev Polugaevsky vs Larry Melvyn Evans (1970)". www.chessgames.com.

- The two rooks are sometimes colloquially referred to as "pigs on the seventh", because they often threaten to "eat" the opponent's pieces or pawns.

- 現代漢語詞典 ISBN 978-962-07-0211-2

- "Article by Dr. Hans Holländer, "CYCLOPES, ELEPHANTS AND CHESS ROOKS"". Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Horton 1959, p. 175

- Stachowski, Marek (January 4, 2002). "Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia". Ksie̦garnia Akademicka – via Google Books.

- "ม้า...เสน่ห์หมากรุก". www.siamsport.co.th. January 14, 2018.

- Global, AIST. "Շախմատային նավակ". chessschool.am.

- Davidson, Henry A. (2012-10-10). A Short History of Chess. Crown. ISBN 978-0-307-82829-3.

- "English :: Kannada Online Dictionary". English :: Kannada Online Dictionary.

- Candler, Howard (January 1, 1907). "How the Elephant became a Bishop: An Enquiry into the Origin of the Names of Chess Pieces". Archaeological Journal. 64 (1): 80–90. doi:10.1080/00665983.1907.10853048.

References

- Alburt, Lev (December 2009), "Back to Basics", Chess Life, 2009 (12): 44–45

- Barden, Leonard (1980), Play Better Chess with Leonard Barden, Octopus Books Limited, p. 10, ISBN 0-7064-0967-1

- Brace, Edward R. (1977), "rook", An Illustrated Dictionary of Chess, Hamlyn Publishing Group, pp. 241–42, ISBN 1-55521-394-4

- Davidson, Henry (1949), A Short History of Chess (1981 paperback), McKay, ISBN 0-679-14550-8

- Fine, Reuben; Benko, Pal (2003), Basic Chess Endings (1941) (2nd ed.), McKay, ISBN 0-8129-3493-8

- Griffiths, Peter (1992), Exploring the Endgame, American Chess Promotions, ISBN 0-939298-83-X

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1996) [First pub. 1992], "rook", The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, pp. 343–44, ISBN 0-19-280049-3

- Horton, Byrne J. (1959), Dictionary of modern chess, New York: Philosophical Library, p. 175, ISBN 0-8065-0173-1, OCLC 606992

- Lasker, Emanuel (1947), Lasker's Manual of Chess, David McKay Company, p. 8, ISBN 0-486-20640-8, OCLC 3636924

- Pandolfini, Bruce (1986), Let's Play Chess, Fireside, ISBN 0-671-61983-7

- Sunnucks, Anne (1970), "rook, the", The Encyclopaedia of Chess, St. Martins Press, ISBN 978-0-7091-4697-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chess rooks. |

- Piececlopedia: Rook by Fergus Duniho and Hans Bodlaender, The Chess Variant Pages