Cittadella (Gozo)

The Cittadella (Maltese: Iċ-Ċittadella), also known as the Castello (Maltese: Il-Kastell),[lower-alpha 1] is the citadel of Victoria on the island of Gozo, Malta. The area has been inhabited since the Bronze Age, and the site now occupied by the Cittadella is believed to have been the acropolis of the Punic-Roman city of Gaulos or Glauconis Civitas.

| Cittadella | |

|---|---|

Iċ-Ċittadella | |

| Victoria, Gozo, Malta | |

View of the Cittadella from the south | |

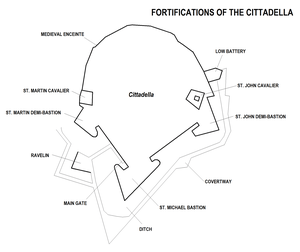

Map of the Cittadella | |

Cittadella | |

| Coordinates | 36°2′47″N 14°14′22″E |

| Type | Citadel |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Government of Malta Various private owners |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Intact |

| Site history | |

| Built | c. 1500 BC (first fortifications) 15th century – 1622 (present fortifications) |

| Built by | Crown of Aragon Order of Saint John |

| In use | c. 1500 BC – 1868 |

| Materials | Limestone |

| Battles/wars | Invasion of Gozo (1551) French invasion of Malta (1798) Gozitan uprising (1798) |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Gelatian de Sessa (attack of 1551) |

During the medieval period, the acropolis was converted into a castle which served as a refuge for Gozo's population. A suburb began to develop outside its walls by the 15th century, and this area now forms the historic core of Victoria. The castle's defences were obsolete by the 16th century, and in 1551 an Ottoman force invaded Gozo and sacked the Cittadella.

A major reconstruction of the southern walls of the Cittadella was undertaken between 1599 and 1622, transforming it into a gunpowder fortress. The northern walls were left intact, and today they still retain a largely medieval form. The new fortifications were criticized in later decades, and plans to demolish the entire citadel were made multiple times in the 17th and 18th centuries, but were never carried out.

The Cittadella briefly saw action during the French invasion and subsequent uprising in 1798; in both cases the fortress surrendered without much of a fight. It remained a military installation until it was decommissioned by the British on 1 April 1868.

The Cittadella contains churches and other historic buildings, including the Cathedral of the Assumption, which was built between 1697 and 1711 on the site of an earlier church. The citadel has been included on Malta's tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 1998.

History

Prehistory and antiquity

Although there is only limited evidence of Neolithic remains in the Cittadella or Victoria, it is likely that the area has been inhabited since the Stone Age, given its size and strategic position. Ceramics discovered inside the Cittadella suggest that the area was a settlement in prehistory. Archaeological remains such as pottery show that the site of the Cittadella was definitely inhabited during the Bronze Age, in the Tarxien Cemetery and Borġ in-Nadur phases of Maltese prehistory. Bronze Age silos were discovered outside the Cittadella in the 19th century, suggesting that during this period the settlement was larger than the present-day citadel.[1]

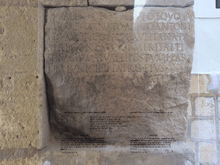

The Victoria area remained the main settlement on Gozo throughout the Phoenician and Roman periods, and it became a settlement known as Gaulos or Glauconis Civitas. The city consisted of an acropolis on the site of the Cittadella, and a fortified town in an area now occupied by part of Victoria. A temple dedicated to Juno is said to have stood on the site now occupied by the cathedral. A few inscriptions and architectural fragments from Gaulos have survived,[2][3] including a 2nd-century AD Latin inscription on a limestone block that was reused in the main gate of the Cittadella.[4]

Remains of walls which might have formed part of the Punic-Roman fortifications of Gaulos have been discovered. In 1969, traces of massive walls were discovered during building works in Main Gate Street (Maltese: Triq Putirjal), to the south of the Cittadella.[5] Further remains were discovered close to the Cittadella during an archaeological excavation in 2017.[6]

Medieval period

During the medieval period, the Roman town was abandoned, and the acropolis was transformed into a castle. The first reference to the castrum of Gozo dates back to 1241. It was sacked by the Genoese in 1274, and a report on its fortifications was ordered two years later. At this point, one-third of Gozo's population lived in or around the Cittadella, and the island's inhabitants were required to spend the night within the citadel. By the end of the 13th century, the Cittadella housed noblemen from Sicily and mainland Italy who represented the Count of Malta. The Cittadella was called terra by the mid-14th century, and an administrative council known as the Università was founded in 1350.[7] In a testament of 1299 it was called castri Gaudisii.[8]

Over time, the Cittadella became too small for the growing population, and by the 15th century the suburb of Rabat began to develop on the site of the Roman town.[lower-alpha 2] This settlement was surrounded by a wall with three gates known as Putirjal, Bieb il-Għajn and Bieb il-Għarb.[10] At this point Malta and Gozo were ruled by the Crown of Aragon, and the Cittadella's fortifications were strengthened.[11] The oldest surviving parts of the walls date back from this period.[12]

Hospitaller rule

_De_belegering_van_Malta_(serietitel)%2C_RP-P-1911-3652.jpg)

Emperor Charles V handed over Malta and Gozo to the Order of St. John in 1530. The Order was in a state of perpetual war against the Ottoman Empire, which had expelled it from its previous base at Rhodes in 1522. At the time the Cittadella was still a medieval castle, and it provided refuge for the Gozitans during Ottoman or Barbary attacks.[13] The largest attack on the Cittadella took place in July 1551, when a large Ottoman force, led by admiral Sinan Pasha, invaded Gozo and besieged the Cittadella. Governor Gelatian de Sessa offered terms of surrender, but they were refused, and the castle fell within a matter of days. The castle was then sacked, and most of the 6,000 Gozitans, who took refuge there, were taken as slaves. The attack left the castle in ruins, but it was rebuilt soon afterwards, although, initially, no efforts were made to modernize it.[13]

The Cittadella was undamaged during the Great Siege of Malta in 1565. Although there had been proposals to demolish the castle and evacuate its inhabitants to Sicily, the castle served an important role during the siege, as it maintained a communication link between besieged Birgu and Christian vessels, and it also reported Ottoman movements to the Order.[14] After the siege, Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette and military engineer Francesco Laparelli visited the Cittadella in order to modernize it, but nothing materialized since at the time the Order was busy constructing its new capital Valletta on mainland Malta. The Cittadella was attacked again by corsairs in 1583.[15]

In 1599, a major reconstruction of the Cittadella begun, under designs of the military engineer Giovanni Rinaldini and under the direction of Vittorio Cassar. The southern walls of the city were completely rebuilt as a bastioned enceinte with a single bastion and two demi-bastions linked by curtain walls, along with two cavaliers, a ditch and outworks.[13] Parts of the northern walls were also rebuilt by the Hospitallers, although they retained a medieval form.[16] The walls surrounding the suburb Rabat were probably demolished at this point. The reconstruction to Rinaldini's and Cassar's designs was completed in around 1622.[17]

Gozo's population stayed within the walls of the Cittadella between dusk and dawn until this curfew was lifted on 15 April 1637.[18] The castle remained the only fortified refuge against attack for the island's inhabitants until Fort Chambray was built in the mid-18th century.[19]

Soon after the reconstruction was complete, the Cittadella's defences were again criticized. In the 1640s, plans were made to demolish the citadel and build a new fortress at Marsalforn. Mines were actually built under the bastions to destroy them, if necessary, but the demolition was never done.[20] The engineer Antonio Maurizio Valperga suggested to rebuild the wall around the suburb and further strengthen the Cittadella, but there were no funds for this proposal.[21]

By the early 18th century the Cittadella had assumed the role of a fortress, with a significant proportion of its houses falling into ruin or being in a poor state. An attack on Gozo took place in 1708, and, in 1715, the engineer Louis François d'Aubigné de Tigné made the same suggestions as Valperga, but a lack of funds prevented any work from being carried out.[21]

French occupation and British rule

On 10 June 1798, the Maltese Islands were invaded by the French. Troops led by Jean Reynier landed near Ramla in the early afternoon, and part of the 95th Demi-Brigade marched to the Cittadella. The fortress held out for some time, but by nightfall it fell to the invaders.[22] The invasion was followed by a French military occupation, but within three months discontent among the population led to revolt on the main island of Malta. The Gozitans rebelled on 3 September, and the French garrison withdrew to the Cittadella, until they capitulated on 28 October after some negotiations. A day later, the British transferred control of the Cittadella to the Gozitans, who set up a provisional government led by Saverio Cassar and briefly administered the island as the independent state La Nazione Gozitana.[23]

When the Gozo Aqueduct was built between 1839 and 1843, a water reservoir was constructed in the Cittadella's ditch.[24] A commemorative obelisk was also built near the reservoir.[25] A road leading from it-Tokk to the Cittadella was constructed in 1854, allowing easier access to the fortified city.[26] The Royal Malta Fencible Regiment moved its Gozo headquarters from the Cittadella to Fort Chambray in 1856, and the fortifications of the Cittadella were decommissioned by the British on 1 April 1868.[27] The Cittadella's fortifications and the ruined buildings within the city were included on the Antiquities List of 1925.[28] During World War II, air raid shelters were dug under the bastions of the Cittadella.[29]

Recent history

The Cittadella's fortifications, including part of the medieval enceinte, are intact. The southern part of the city, where the cathedral and other buildings are located, is in good condition, but the buildings in the northern part are largely in ruins. Most of these ruins date back to the medieval period, and they contain archaeological deposits. Since 1998, the citadel has been included on Malta's tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[30]

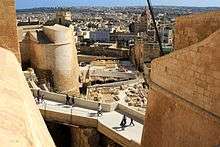

In 2006, the first plans were made to restore the Cittadella, as part of a project that also included the restoration of the fortifications of Valletta, Birgu and Mdina on mainland Malta.[31] The restoration of the Cittadella consisted of two projects which were co-funded under the European Regional Development Fund. The first was aimed at stabilizing and consolidating the fortifications and their underlying bedrock,[32] and it began in 2008.[33][12] This project was undertaken by the Restoration Unit at a cost of around €7 million.[32]

The second project was undertaken by the Ministry for Gozo between 2014 and 2016 at a cost of €14 million. The façades of the main buildings in the Cittadella were restored, while the ruins were acquired by the government and were cleaned and consolidated. The piazza and streets were paved, and the ditch was rehabilitated as a leisure area. A breach in the bastions was closed off with a door, and accessibility and safety measures were undertaken.[32] The 19th-century reservoir in the ditch was also converted into the Cittadella Visitors' Centre, with this project being entrusted to Martin Xuereb & Associates[34] and Sarner International.[35] The restored Cittadella was inaugurated on 30 June 2016.[36] The Cittadella Visitors' Centre has won multiple local and international awards since its inauguration.[34][37][38]

During the course of restoration, various architectural features and archaeological remains were unearthed. A small structure consisting of two sets of stones in circular arrangements was discovered in Cathedral Square in December 2014. Its age and purpose are unknown.[39][40] Bronze Age silos were also rediscovered. Parts of the Hospitaller fortifications which had been obscured by British interventions in the mid-19th century were also rediscovered during the restoration works. These include a ramp with a drawbridge which served as the original entrance to the fortress, and a sally port within a flank of St. Michael's Bastion.[41][42] The archaeological discoveries were incorporated into the final design of the project.[32]

Architecture

The Cittadella is built on a promontory overlooking the present day city of Victoria. This location was originally chosen because it is a naturally defensible hill, dominating the surrounding countryside and having views of large parts of the coastline.

Fortifications

The fortifications of the Cittadella consist of a semi-circular enceinte in the northern end of the city, and bastions linked together with curtain walls in the south. The northern walls are built on the perimeter of the natural plateau, so they were difficult to attack. They were originally built in the 15th century, although large portions of the walls were rebuilt by the Hospitallers or in modern times. The northern walls include the remains of a collapsed medieval wall tower, a blocked-up sally port,[43] a lookout post and some walled-up windows.[16] Masonry revetments are built in depressions within the cliff face below the northern walls.[44]

The southern perimeter of the city consists of a 17th-century bastioned enceinte which was built by the Hospitallers. A large arrowhead-shaped bastion known as St. Michael's Bastion is built at the southernmost end of the city, while two demi-bastions – St. Martin's and St. John's Demi-Bastions – are located at the west and east ends of the city. Flat-roofed échauguettes are built on the salient of each demi-bastion.[45][46] St. Michael's Bastion also had an echaugette but this was replaced by a clock tower in 1858.[47] A small gunpowder magazine is located at the junction between St. John's Demi-Bastion and the medieval enceinte.[48]

The bastions are linked together by curtain walls. The one between St. Martin's Demi-Bastion and St. Michael's Bastion contains the Main Gate,[49] a modern arched opening and a clock tower.[50] The wall between St. Michael's Bastion and St. John's Demi-Bastion is known as St. Philip's Curtain,[51] and its upper part contains slit-like openings which open into a series of magazines which are now used as craft shops. These rooms support a walkway along the ramparts.[52][53]

Cavaliers were also built close to each demi-bastion. St. Martin's Cavalier is located between the medieval enceinte and St. Martin's Demi-Bastion, and it is only partially intact, its upper portions having been pulled down.[54][55] St. John's Cavalier, which is found near St. John's Demi-Bastion and the rear of the cathedral, was completed in 1614. A freestanding room was constructed on its roof in 1701 for use as a gunpowder magazine.[56]

A pentagonal artillery battery known as the Low Battery is grafted below the walls at the easternmost extremity of the fortress, close to St. John's Demi-Bastion.[57] The southern perimeter of the Cittadella is surrounded by a ditch, which originally extended from St. Martin's Demi-Bastion to the Low Battery but now begins at St. Michael's Bastion due to 19th-century alterations.[24] A covertway with a single place-of-arms runs along the ditch.[58] A steep glacis was located outside the covertway, but this has been built up.[13] A small triangular ravelin stands near the entrance to the city, but this has lost most of its original stonework and has been converted into a garden, losing its legibility as part of the fortress in the process.[59]

Churches

One of the major landmarks in the Cittadella is the Cathedral of the Assumption, which is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Gozo. According to tradition, it stands on the site of a Roman temple dedicated to Juno, which was eventually converted to a Christian church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The cathedral is believed to have been destroyed after the Maltese islands fell to the Arabs. A second church was built in the medieval period, and the earliest mentions of a parish church within the Cittadella date back to the 13th century. This church was enlarged in the 15th and 16th centuries, and it was damaged in the 1551 attack, although it was repaired within a few years. The building was damaged during the 1693 Sicily earthquake, and it was subsequently demolished to make way for the present structure, which is a Baroque building constructed between 1697 and 1711 to designs of Lorenzo Gafà,[60] a Maltese architect who also built the Cathedral of Mdina on mainland Malta. Extensive remains of a Roman temple were found during construction,[61] and some remains from this era still survive beneath the cathedral.[62] The church became a cathedral with the establishment of the diocese of Gozo in 1864. Today, the building is most famous for a remarkable trompe l'oeil on its ceiling, which depicts the interior of a dome that was never built.[63] This was painted by the Sicilian artist Antonio Manuele.[64] A small building behind the cathedral houses the Cathedral Museum.[65]

Two chapels are also found inside the Cittadella. The Chapel of St. Joseph, known as ta' fuq is-sur ("on the bastions"), was originally built in around the 11th century, and it was dedicated to Nicholas of Bari. The present building was built in 1625, possibly to designs of Vittorio Cassar, and it might incorporate parts of the original chapel.[66]

The other chapel is dedicated to Saint Barbara, and it is known as "within the Walls". Its site was originally occupied by a chapel dedicated to John the Baptist, but this was deconsecrated in 1575. The site was given to the Confraternity of St. Barbara in 1598, who built the existing chapel in the early 17th century, during the magistracy of Alof de Wignacourt and around the same time when the fortifications were being reconstructed. This chapel is annexed to the cathedral.[67]

Other chapels dedicated to Saint Lawrence and Our Saviour existed within the Cittadella during the medieval period. These were deconsecrated following Inquisitor Pietro Dusina's visit in 1575, and no remains have survived today.[68]

Other buildings

The main square of the Cittadella, which is known as Pjazza tal-Katidral (Cathedral Square), contains the Law Courts. These are housed in two buildings, one of which was purpose-built as a courthouse, and another, which was formerly the Governor's Palace,[69] built in the early 17th century.[70] Opposite the Governor's Palace is the Bishop's Palace.[71] Adjoining the Chapel of St. Joseph, there is a residential palace that was built by Bishop Baldassare Cagliares in 1620.[72] A fountain against a wall is a commemoration of the naming of the city as Victoria, the then Queen of Great Britain, on 10 June 1887.[73]

The following buildings are now open to the public as museums:

- The Old Prison, located behind the Law Courts, which was used as a prison from the 16th century to 1962. It contains well-preserved prison cells and other exhibitions.[74]

- The Gozo Nature Museum, which is dedicated to Gozo's geography, geology and natural science. It is located within a group of 17th-century houses which, at times, had been used as an inn.[75][76]

- The Gozo Museum of Archaeology, which is dedicated to Gozitan history from the prehistoric to medieval periods,[77] is located within a 17th-century house that was originally known as Casa Bondi.[78]

- Gran Castello Historic House, which is dedicated to Gozitan folklore. It is housed in a cluster of early 16th-century houses.[79]

These four museums are run by Heritage Malta.[80]

Notes

- Also known by variants of these names, including Citadel or Gran Castello.

- The name Rabat originally referred to the historic centre of the main town on Gozo, excluding the Cittadella. In 1887 Rabat was merged with the Cittadella and surrounding neighbourhoods to form the city of Victoria. Today the name Rabat is used to refer to the entire city of Victoria in the Maltese language.[9]

References

- MEPA 2012, pp. 28–29.

- MEPA 2012, p. 30.

- Pericciuoli Borzesi, Giuseppe (1830). The historical guide to the island of Malta and its dependencies. Malta: Government Press. pp. 83–84.

- MEPA 2012, p. 192.

- MEPA 2012, p. 34.

- Carabott, Sarah (11 May 2017). "Ancient walls uncovered just outside Ċittadella". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 12 May 2017.

- MEPA 2012, pp. 37–38.

- Mizzi, Pawlu (19 December 1993). "Tagħrif dwar il-belt il-qadima t'Għawdex (2)" (PDF). il-Mument - il-Hadd. p. 34. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Grech, Joseph (8 June 2018). "Victoria or Rabat t'Għawdex – what's in a name?". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018.

- MEPA 2012, p. 44.

- Cassar, George (2014). "Defending a Mediterranean island outpost of the Spanish Empire – the case of Malta". Sacra Militia (13): 59–68.

- Cocks, Joanne (10 December 2012). "Gozo's Cittadella getting €6m restoration". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016.

- "Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2016.

- MEPA 2012, pp. 42–43.

- MEPA 2012, p. 43.

- "Medieval enceinte – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015.

- MEPA 2012, pp. 43–44.

- "History". Victoria Local Council. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018.

- Buhagiar, Konrad; Cassar, JoAnn (2003). "Fort Chambray: The genesis and realization of a project in eighteenth-century Malta" (PDF). Melita Historica. 13 (4): 347–364. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2016.

- "Restoration of the Cittadella". MilitaryArchitecture.com. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- MEPA 2012, pp. 45–46.

- Hardman, William (1909). "Chapter VII – Attack and Capture of Malta by the French". A history of Malta during the period of the French and British occupations, 1798–1815. London: Longmans, Green & Co. p. 47.

- Schiavone, Michael J. (2009). Dictionary of Maltese Biographies A–F. Malta: Publikazzjonijiet Indipendenza. pp. 533–534. ISBN 9789993291329.

- "Ditch – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2015.

- Rix, Juliet (2013). Malta and Gozo. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 290. ISBN 9781841624525.

- MEPA 2012, p. 47.

- "1868–2018; 150 years as a non-active fortress" (PDF). Heritage Malta. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2018.

- "Protection of Antiquities Regulations 21st November, 1932 Government Notice 402 of 1932, as Amended by Government Notices 127 of 1935 and 338 of 1939". Malta Environment and Planning Authority. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016.

- Amaira, Ruth (3 February 2018). "Restoration of war-time shelters under The Cittadella and "Il-Loġġa tal-Palju" in Gozo". TVM. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- "Cittadella (Victoria – Gozo)". UNESCO Tentative List. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016.

- Zammit, Ninu (12 December 2006). "Restoration of forts and fortifications". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- Cremona, John (Winter 2017). "Cittadella – the Re-Discovered Treasure" (PDF). The Gozo Observer. 35: 22–23.

- "Ambitious Citadel restoration project". Times of Malta. 10 August 2008. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016.

- "Cittadella Visitor Experience wins Prix d'Honneur in Major Regeneration Project category". The Malta Independent. 22 January 2017. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017.

- "Cittadella Visitors' Centre". Sarner International. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018.

- "PM inaugurates Gozo Citadella restoration project". TVM. 30 June 2016. Archived from the original on 12 November 2016.

- "Ċittadella visitors' centre wins international award". Times of Malta. 15 July 2017. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- "Gozo's Cittadella Visitors' Centre receives prestigious award". TVM. 8 April 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- Barry, Duncan (11 December 2014). "Cittadella: Discovery in Cathedral Square; age, use of structure still to be determined". The Malta Independent.

- "Archaeologists study discovery at Gozo cathedral square". Times of Malta. 11 December 2014. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015.

- Dalli, Kim (21 June 2014). "Original entrance to Gozo Citadel exposed". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016.

- Spiteri, Stephen C. (14 July 2014). "Unearthed features at the Cittadella". MilitaryArchitecture.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017.

- "Medieval sally-port on north enceinte – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2016.

- "Masonry revetments along the foot of the cliff face – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2016.

- "St Martin Demi-bastion – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015.

- "St John Demi-Bastion – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2015.

- "St Michael Bastion – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015.

- "Gunpowder Magazine – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2016.

- "Main gate – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2016.

- "Curtain wall linking St Martin Demi-bastion to St Michael Bastion – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2016.

- MEPA 2012, pp. 236–237.

- "Curtain wall linking St John Demi-bastion to St Michael Bastion – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2016.

- "Magazines (Craft Shop)" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2016.

- Spiteri, Stephen C. (2013). "In Defence of the Coast (I) – The Bastioned Towers". Arx – International Journal of Military Architecture and Fortification (3): 70–74. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "St Martin Cavalier – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015.

- "St John Cavalier – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015.

- "Low Battery – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015.

- "Covertway – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2016.

- "Ravelin – Cittadella" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2015.

- "Cathedral of the Assumption of the Madonna" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 27 August 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2016.

- Bonanno, Anthony (2005). Malta: Phoenician, Punic, and Roman. Midsea Books. p. 344. ISBN 9789993270355.

- Mallia, Steve (22 December 2003). "Roman wall unearthed at Gozo cathedral". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Chambry, D.; Trump, David H. (1978). Malta. Nagel Publishers. p. 173. ISBN 9782826307112.

- Bezzina, Joseph (16 August 2009). "Trompe l'oeil at Gozo Cathedral". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017.

- "Cathedral Museum" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2016.

- "Church of St Joseph" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 27 August 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2016.

- "Church of Sta Barbara" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 27 August 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2016.

- Scerri, John. "Rabat (Victoria)". malta-canada.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016.

- "Law Courts" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2016.

- "The Courts". The Judiciary of Malta. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016.

- "Bishop's Palace" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2016.

- "Cagliares Palace" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2016.

- "Attard, G. G. (2019, May 19). Victoria Regina et Imperatrix – 200 years from her birth. The Sunday Times of Malta, pp. 56-57" (PDF).

- "Old Prison". Heritage Malta. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018.

- "Natural Science Museum" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2016.

- "Gozo Nature Museum". Heritage Malta. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018.

- "Gozo Museum of Archaeology". Heritage Malta. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018.

- "Archaeology Museum" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2016.

- "Gran Castello Historic House". Heritage Malta. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018.

- "Malta's National Museums & Sites". Heritage Malta. Archived from the original on 26 July 2017.

Bibliography

- "Environmental Planning Statement for the Creation of Stabilised Slopes and Car Parking at Rabat, Gozo – Responses to MEPA and other stakeholders' comments" (PDF). Malta Environment and Planning Authority. Fgura. August 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2015.

Further reading

- Spiteri, Stephen C. (2001). Fortresses of the Knights. Book Distributors Limited. ISBN 9789990972061.

- Vella, Godwin (2011). The Gran Castello at Rabat, Gozo: an appreciation of the civil architectural legacy. Wirt Għawdex. ISBN 9789995700393.

External links

![]()