Sagas of Icelanders

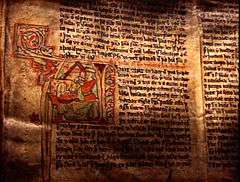

The sagas of Icelanders (Icelandic: Íslendingasögur), also known as family sagas, are one genre of Icelandic sagas. They are prose narratives mostly based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and early eleventh centuries, during the so-called Saga Age. They are the best-known specimens of Icelandic literature.

| Part of a series on |

| Old Norse |

|---|

|

|

Dialects Old West Norse Greenlandic Norse)

Old East Norse

|

|

Ancestors

|

|

|

They are focused on history, especially genealogical and family history. They reflect the struggle and conflict that arose within the societies of the early generations of Icelandic settlers.[1]

Eventually many of these Icelandic sagas were recorded, mostly in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The 'authors', or rather recorders of these sagas are largely unknown. One saga, Egils saga, is believed by some scholars[2][3] to have been written by Snorri Sturluson, a descendant of the saga's hero, but this remains uncertain. The standard modern edition of Icelandic sagas is known as Íslenzk fornrit.

Historical time frame

Among the several literary reviews of the sagas is that by Sigurður Nordal's Sagalitteraturen, which divides the sagas into five chronological groups distinguished by the state of literary development:[4]

- 1200 to 1230 – Sagas that deal with skalds (such as Fóstbrœðra saga)[4]

- 1230 to 1280 – Family sagas (such as Laxdæla saga)[4]

- 1280 to 1300 – Works that focus more on style and storytelling than just writing down history (such as Njáls saga)[4]

- Early fourteenth century – Historical tradition[4]

- fourteenth century – Fiction[4]

List of Sagas

- Atla saga Ótryggssonar

- Bandamanna saga – Bandamanna saga

- Bárðar saga Snæfellsáss

- Bjarnar saga Hítdælakappa

- Droplaugarsona saga

- Egils saga Skalla-Grímssonar – Egil's Saga

- Eiríks saga rauða – Saga of Erik the Red

- Eyrbyggja saga

- Færeyinga saga

- Finnboga saga ramma

- Fljótsdæla saga

- Flóamanna saga

- Fóstbræðra saga (two versions)

- Gísla saga Súrssonar, (two versions) of an outlaw poet – Gísla saga

- Grettis saga – Saga of Grettir the Strong

- Grænlendinga saga – Greenland saga

- Gull-Þóris saga

- Gunnars saga Keldugnúpsfífls

- Gunnlaugs saga ormstungu

- Hallfreðar saga (two versions)

- Harðar saga ok Hólmverja

- Hávarðar saga Ísfirðings – The saga of Hávarður of Ísafjörður

- Heiðarvíga saga

- Hrafnkels saga

- Hrana saga hrings (post-medieval)

- Hænsna-Þóris saga

- Kjalnesinga saga

- Kormáks saga

- Króka-Refs saga

- Laurentius Saga

- Laxdæla saga

- Ljósvetninga saga (three versions)

- Njáls saga

- Reykdæla saga ok Víga-Skútu

- Skáld-Helga saga (known only from rímur and later derivations of these)

- Svarfdæla saga

- Valla-Ljóts saga

- Vatnsdæla saga

- Víga-Glúms saga

- Víglundar saga

- Vápnfirðinga saga

- Þorsteins saga hvíta

- Þorsteins saga Síðu-Hallssonar

- Þórðar saga hreðu

- Ölkofra saga

A small number of sagas are thought to have existed and now to be lost. One example is the supposed Gauks saga Trandilssonar.

See also

- Norse Saga

- Family saga

References: English translations

- Örnólfur Thorsson (1997). The Complete Sagas of Icelanders. 5 vols. Reykjavik: Leifur Eiriksson Publishing Ltd.[5]

- Örnólfur Thorsson, et al. (eds.) (2000) The Sagas of Icelanders: a selection. Penguin Books

- Myers, Ben (2008-10-03). "The Icelandic Sagas: Europe's most important book?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-08-24.

- Egil's Saga, English translation, Penguin Books, 1976, introduction by Hermann Pálsson and Paul Edwards, p. 7

- Sigurður Nordal had this to say in his edition of Egils saga: "This matter will never be settled fully with the information we now have. … As for me, I have become more and more convinced, as I gained a better understanding of Egils saga that it is the work of Snorri, and I will henceforth not hesitate to count the saga among his works, unless new arguments are presented, which I have overlooked."

- Lönnroth, Lars (1976). Njáls Saga. London: University of California Press. pp. 204–205. ISBN 0-520-02708-6 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Complete Sagas of Icelanders". Sagas.is. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

References: studies

- Arnold, Martin (2003). The Post-Classical Icelandic Family Saga. Lampeter: Edwin Mellen Press

- Karlsson, Gunnar (2000). The History of Iceland. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

- Liestol, Knut (1930). The Origin of the Icelandic Family Sagas. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press

- Miller, William Ian (1990). Bloodtaking and Peacemaking: Feud, Law, and Society in Saga Iceland. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

External links

- Icelandic Saga Database – a website with all the Icelandic sagas, along with translations into English and various other languages

- Proverbs and Proverbial Materials in the Old Icelandic Sagas

- Icelandic sagas – a selection in Old Norse

- Sagnanet – photographs of some of the original manuscripts

- Harmony of the Vinland voyages

- Icelandic Saga Map – an online digital map with the geo-referenced texts of all of the Íslendingasögur