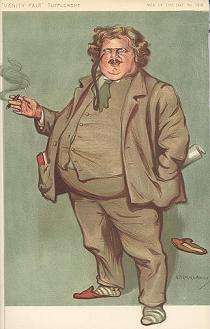

G. K. Chesterton

"He is so happy! I can almost believe he has found God."

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) was an English author and Catholic apologist in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Though best known for his Father Brown mysteries, he wrote prodigiously in a number of genres, both poetry and prose, fiction and non-fiction (the American Chesterton Society reckons that if you wanted to write as many essays as he did you'd have to write one every day for around eleven years).

Chesterton's writing is characterized by a vivid style, with much use of word-play and paradox, and by an often polemical though nearly always hugely good-natured tone. (Typically, he would mock his own large girth and heavy drinking.) Common themes in "GKC's" writing include the romance of everyday life, the superiority of traditional to modern ideals, and the dignity of the common man and ordinary pleasures such as smoking and drinking, especially as contrasted with the puritanical élites of either capitalist conservatives or socialist progressives (whose opposition to each other he considered largely a sham). His swashbuckling attitude toward life was exemplified as well in his personal appearance by the brigandly broad hat, cape, and sword-stick devised for him by his adored wife, Frances.

Chesterton had a great influence on many writers, especially in the early twentieth century. He was for many years president of The Detection Club, an organization for writers of Mystery Fiction (the oath of which, devised by GKC, demanded that members write only Fair Play Whodunnits); such writers as Agatha Christie, Fr. Ronald Knox, and Dorothy L. Sayers were co-members. Chesterton's fellow Roman Catholics Hilaire Belloc (Chesterton and Belloc were collectively nicknamed the Chesterbelloc by Chesterton's "friendly enemy" George Bernard Shaw) and JRR Tolkien were admirers, and GKC's apologetic writings (especially Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man) helped inspire CS Lewis to (re-)convert to Christianity. Golden Age mystery author John Dickson Carr was such a strong admirer that he modeled his most famous character, Dr. Gideon Fell, on Chesterton's appearance. More recently, Neil Gaiman modeled a character in The Sandman after him, got his inspiration for London Below from The Napoleon of Notting Hill (as he relates here), and Gaiman and Terry Pratchett dedicated Good Omens "To G.K. Chesterton: A Man Who Knew What Was Going On."

- Father Brown stories

- The Man Who Was Thursday

- Above Good and Evil: The claim of the Communist in "The Unmentionable Man" (in The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond.)

- Alliteration: Chesterton loved this trope.

- Bored with Insanity: Andrew Home in "The Conversion of an Anarchist".

- As well as Gabriel Syme in The Man Who Was Thursday.

- Color-Coded for Your Convenience: A character with red hair is almost always Good in Chesterton. Less frequently, Blond Guys Are Evil -- especially if the blondness looks somehow artificial ("gilded").

- Which may have something to do with the fact that Chesterton's beloved wife was a redhead.

- Although Gabriel Gale, the protagonist of The Poet and the Lunatics, is blond.

- As far as redheads go, The Man Who Was Thursday had it both ways: Gregory's sister is the symbol of all that is good, and Gregory, equally red-headed, is not good at all. Their red hair is seen as part and parcel to their respective goodness and evilness.

- Confessional: Very common in GKC's works -- The Surprise is one example.

- The Cuckoolander Was Right: Chesterton loved this. Many of his characters take "wise fool"-style radical behavior Up to Eleven.

- Deadpan Snarker: During the First World War: "Mr. Chesterton, why aren't you out at the front?" "Madam, if you go around to the side, you will see that I am." (in reference to his weight). Many of Chesterton's characters share this trait.

- Democracy Is Bad: Or at least have definite problems that raise the possiblity of a return of monarchy.

- Duel to the Death: The Ball and the Cross

- The Ending Changes Everything: His short poem The Donkey is clearly about how ridiculous and pathetic a creature the donkey is... until the last line completely overthrows all of the imagery from the rest of the poem.

- Famous Last Words: "The issue now is clear. It is between light and darkness; and everyone must choose his side." He then added to his secretary Dorothy Collins, who had just entered the room, "Hello, my dear."

- Fairy Tale: Often cited by GKC (as, for instance, the actors playing "Puss-in-Boots" in The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond), and occasionally authored by him -- e.g., The Coloured Lands.

- Fat and Skinny: Chesterton was fond of this trope (see Thomas Aquinas), and he and his friend Shaw embodied it...with Shaw as the skinny guy, of course.

- Fertile Feet: In Tales of the Long Bow

- The Final Temptation: In The Ball and the Cross, MacIan and Turnbull are each tempted with visions of the establishment of their respective Utopias.

- Expy: Rupert Grant in The Club of Queer Trades has been called a parody of Sherlock Holmes.

- Gainax Ending: Most noticeably at the end of The Ball and the Cross and The Man Who was Thursday.

- Gentleman Thief: Flambeau and "The Ecstatic Thief" in Four Faultless Felons are examples.

- God: Is always lurking in the background in GKC's stories, and comes very near to the foreground in some. The Author in The Surprise is one (partial) example.

- Golden Mean Fallacy: The Duke in Magic embodies this trope.

- Gorgeous Period Dress: In The Napoleon of Notting Hill, King Auberon forces the representatives of various London districts to dress in mediæval-style robes and to be accompanied by heralds and halberdiers. Also, a plot point in "The Three Horsemen of Apocalypse" in The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond.

- The Greatest Story Never Told: The plot of The Judgement of Dr. Johnson; the stories of the Club of Misunderstood Men in Four Faultless Felons -- GKC was very fond of this trope.

- Happily Married: Very common in Chesterton -- no doubt reflecting his own happy marriage. There are, for instance, the Gahagans in The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond.

- Happy Ending: In keeping with his basic theme of the essential goodness of life, Chesterton nearly always ends his works happily.

- Have a Gay Old Time: The Club of Queer Trades

- He Also Did: Depending on where you're standing, G.K. Chesterton, the famous detective story author, was also a Catholic apologist, or the great Catholic apologist G.K. Chesterton, also wrote Mystery Fiction. Oh, and he was also a literary critic, a poet, a journalist, and a bit of a cartoonist, as well.

- Heel Realization: He came to realize how sinful racism is and apparently repented.

- Historical Domain Character: In The Ballad of the White Horse, Alfred the Great and Gunthrum; in his play, The Judgement of Dr. Johnson, Dr. Samuel Johnson, John Boswell, Edmund Burke, etc.

- Historical Hero Upgrade: "Lepanto" pumps up Don Juan of Austria ("The Last Knight of Europe") from Christian military hero to saviour of the western world from the hordes of darkness and its own political corruption.

- The Ballad of the White Horse does much the same for King Alfred.

- Hypocrite: Though there are many examples of the straight version of this trope in GKC (as, for instance, in "The Man Who Shot the Fox"), Chesterton is peculiarly fond of a particular subversion of it -- the good man who pretends to be wicked. An outstanding example, in which this trope forms the whole theme of the book, is Four Faultless Felons.

- The Infiltration: Rather subtly, "The Five of Swords."

- Infraction Distraction

- Kick Them While They Are Down: Happens in The Ball and the Cross

- Last Kiss: John and Olive in The Return of Don Quixote.

- Leonine Contract

- Love At First Sight: Manalive and many others.

- Mad Mathematician: In "The Moderate Murderer" in Four Faultless Felons, Tom Traill's tutor, Hume, affects bizarre behaviour as a means to focus the underdeveloped boy's attention.

- Magicians Are Wizards: Magic

- Make-up Is Evil: In The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond, one character comments on how this trope is decreasing.

- Meaningful Rename: In The Return of Don Quixote.

- New Era Speech: Three contrasting ones by the same character in The Ball and the Cross.

- No Celebrities Were Harmed: In The Napoleon of Notting Hill, King Auberon is modeled on English author Max Beerbohm. Chesterton himself was later subject to this; his friend and opponent George Bernard Shaw caricatured him as "Immenso Champernoon" in an unproduced portion of Back to Methuselah.

- Obfuscating Insanity: Manalive.

- One Scene, Two Monologues: In The Return of Don Quixote, Herne and Archer talk about the play Blondel the Troubadour. One is discussing his chances to show off in it; the other is discussing its philosophical underpinnings. Neither of them figures out that they are talking past each other.

- Poisonous Friend: Marshal Grock to the Prince in "The Three Horsemen of Apocalypse" in The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond.

- Pull a Rabbit Out of My Hat: In Magic Patricia Carleon imagines conjurors must be able to provide meals for themselves inexpensively by pulling rabbits out of their hats.

- Real Dreams Are Weirder: Analyzed in the essay "Dreams" as the reason many literary dream sequences don't ring true.

- The Reveal: One of the bases of Mystery Fiction, of course, but common throughout GKC's work, even his non-fiction, as one of his fundamental themes. It comes clearly to the fore, for instance, in his posthumously published play, The Surprise.

- Revealing Coverup: The conspiracy of "The Word" in "The Loyal Traitor" in Four Faultless Felons.

- Rightful King Returns: The republic in The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond is in danger of this.

- Rock Beats Laser: In The Return of Don Quixote, mediaeval recreationists go out to arrest some people, with halberds rather than guns, and are scorned as foolish. They succeed.

- Royal Blood: Royalty abounds in GKC's from his earliest to his latest works -- and, oddly, for such a fan of the French Revolution, is very often treated with real sympathy, as in "The Unmentionable Man" in one of Chesterton's last books, The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond. (See also the next entry.)

- Ruritania: "The Loyal Traitor," in Four Faultless Felons, takes place in the mythical Teutonic kingdom of Pavonia (specifically stated not to be in the Balkans while directly referencing Hope's novel). There are also two unnamed rival Balkan kingdoms in "The Tower of Treason."

- Sliding Scale of Idealism Versus Cynicism: The Ball and the Cross.

- Stage Magician: The Conjuror in Magic

- Still Wearing the Old Colors: In an early scene in The Napoleon of Notting Hill', the deposed president of Nicaragua goes to some trouble to wear the colours of his now-conquered country.

- Sword Cane: Carried by GKC himself. He brainstormed by poking at the couch cushions in his office with it.

- Trailers Always Spoil: Commented on in the poem "Commercial Candour":

"...For the front of the cover shows somebody shot

And the back of the cover will tell you the plot."

- Trouble Entendre: Subverted in "The White Pillars Murder."

- Two Rights Make a Wrong: One of the Paradoxes of Mr Pond, "The Three Horsemen of the Apocalypse", concerns a field marshal whose soldiers were too eager to obey his orders, with the result that the orders were not carried out. If only one man had been that loyal it would have worked, but with two soldiers determined to fulfill his orders to execute a poet, the man ends up released.

- Unaccustomed as I Am to Public Speaking: Referenced in Magic -- and, indeed, in nearly every context, GKC was fond of referencing his own debility. Did he not know?

- Vitriolic Best Buds: With George Bernard Shaw in Real Life.

Chesterton: George, you look like you just came from a country in a famine!

Shaw: G.K., you look like you caused it!

- Warrior Poet: In The Ballad of the White Horse, there is not only Elf the minstrel ("whose hand was heavy on the sword, though light upon the string..."), but King Alfred himself.

- Water Tower Down: Threatened in The Napoleon of Notting Hill

- When Trees Attack: "The Trees of Pride"

- Woman in White: Tales of the Long Bow

- Women Are Wiser: Mr. Isidore Green, in "The Ecstatic Thief" section of Four Faultless Felons, is rather woolly-headed about his affairs, and has to depend on his much more practical wife to take care of him.

- May be based on the author's own experience: he was absentminded, and apparently once telegraphed his wife while wandering around London, "Where am I supposed to be?" Her answer: "Home."

- Would Not Shoot a Civilian

- Writer on Board: Common with GKC, as in The Ball and the Cross, when Father Michael (a Bulgarian monk) and Evan MacIan (a Scottish Highlander) both talk at times suspiciously like an English literateur.

- Ye Goode Olde Days: GKC was (and is) often accused of over-romanticizing the past, though he claimed he was merely correcting a falsely "progressive" view of history.

- Zeerust: Deliberately averted in The Napoleon of Notting Hill, in which the future is the same as the 1904 present, only more so. This is justified in the foreword, wherein GKC explains a game people play, called "Cheat the Prophet", wherein they listen politely to what clever men say about what will happen in the future, wait until the clever men are dead, and then go and do something completely different; as the only thing that has not been guessed is that nothing will change, the people...don't.

- Except that Chesterton himself just got through predicting it -- this probably also qualifies as a preemptive Lampshade Hanging on the impending obsolescence of his prediction.