The Man Who Was Thursday

"First of all, what is it really all about? What is it you object to? You want to abolish Government?"

"To abolish God!" said Gregory, opening the eyes of a fanatic. "We do not only want to upset a few despotisms and police regulations; that sort of anarchism does exist, but it is a mere branch of the Nonconformists. We dig deeper and we blow you higher. We wish to deny all those arbitrary distinctions of vice and virtue, honour and treachery, upon which mere rebels base themselves. The silly sentimentalists of the French Revolution talked of the Rights of Man! We hate Rights as we hate Wrongs. We have abolished Right and Wrong."

"And Right and Left," said Syme with a simple eagerness, "I hope you will abolish them too. They are much more troublesome to me."

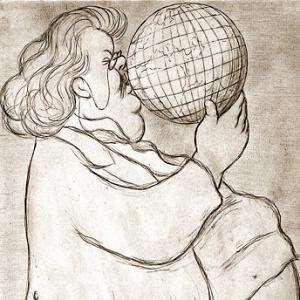

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare is a metaphysical Thriller by famed author G. K. Chesterton, and stands alongside his Father Brown stories as his most famous work.

The story concerns special detective Gabriel Syme, a member of a secret police force dedicated to fighting the forces of Anarchy, who encounters a self-professed anarchist poet by the name of Lucian Gregory. After a spirited debate on the subject of Order Versus Chaos, Gregory invites Syme to a secret meeting of the anarchist force to which he belongs. There, Syme manages to get himself elected as the new Thursday on the anarchists' supreme council, the Council of Days, where each member is named for a different day of the week, in order to penetrate the anarchist organization and bring it down. The council is led by the terrifyingly cheerful and enigmatic figure of Sunday, and what follows is Syme's attempt to stay sane in the face of what seems to be true evil, and to answer the maddening question: "Who is Sunday?"

The book deals with the conflict of Order and Chaos, and serves to deconstruct the concept of the Bomb Throwing Anarchist (which was popular at the time) in favour of dealing with philosophical anarchism, that Chesterton felt to be actual nihilism that seeks to abolish not just government and authority, but the very concepts of good, evil, and God. It contains elements of the spy novel, Mystery Fiction, Satire, humour, and horror, and has also had a rather eclectic variety of fans in the literary world, including Michael Collins, Jorge Luis Borges, and Franz Kafka.

You can read it online here.

- All Just a Dream: No, that's not a spoiler; it's right there in the subtitle. Chesterton actually wrote an article specifically criticizing the readers and critics who overlooked that in their interpretations of the work.

- To be fair, it's not totally clear given that the protagonist "wakes" to find himself walking and in the middle of a conversation.

- Alternate Character Interpretation: In-Universe example: Almost a whole chapter is dedicated to each Council member's different interpretation of Sunday.

- Badass Boast: Sunday gives one before revealing he is the man in the dark room.

- Beauty Equals Goodness: Good characters look wholesome, evil characters look creepy in some way--and seeing what a character really looks like is enough to convince the other characters what side he's really on.

- But many characters are wearing some form of disguise. The beauty that marks their goodness is subsurface.

- Beneath Notice: Subverted; Sunday's method of keeping the anarchists away from suspicion is for them to claim explicitly to be Bomb-Throwing Anarchists, while appearing to be (eccentric) respectable gentlemen.

- Bizarrchitecture: Saffron Park, as well as the homes of Monday and Sunday.

- Blue Blood: A recurring theme of the novel is that the working/lower class, even criminals, will never be swayed into philosophical anarchy, only the rich/upper class and intellectuals. It appears to be subverted in a big way later in the novel, but is actually played straight.

- Bomb Throwing Anarchist: Deconstructed

- Bored with Insanity: Syme embraced Order and rejected radicalism because his whole family was made up of radicals for various causes and ideologies.

Being surrounded with every conceivable kind of revolt from infancy, Gabriel had to revolt into something, so he revolted into the only thing left -- sanity.

- Catapult Nightmare: Averted, and lampshaded in the process.

- Cold-Blooded Torture: Tuesday is threatened with this.

- Color-Coded for Your Convenience: A character with red hair is almost always Good in Chesterton. Less frequently, Blond Guys Are Evil, especially if the blondness looks somehow artificial ("gilded"). However, this novel subverts this with the honourable protagonist Syme (who is blond) and the antagonist(?) Gregory (maybe), who is red-haired.

- On the other hand, his sister, also red-haired, is unambiguously good -- and probably a tribute to Chesterton's own wife, Frances.

- Costume Porn: The masquerade costumes in the last chapter -- not done in excruciating detail, though.

- Day of the Week Name: Naturally. Though in a slight aversion, the weekday names are actually code names (with the possible exception of Sunday) for the seven leaders of an anarchist organization. In another aversion, they turn out to be based on the days of the Creation week, slightly adjusted.

- Deadpan Snarker: Syme and Wednesday/ Rickert especially, though all the characters have their moments.

- Did We Just Have Tea with Cthulhu?

- Dress-Coded for Your Convenience: At the climax of the story, each Council member is dressed in clothes featuring a motif based on what was created on his respective day in Genesis: Monday has a single white stripe for the light created on the first day; Tuesday, blue parted robes; Wednesday, a tree/green motif; Thursday, the sun and moon; Friday, fish and birds, and Saturday, beasts and a man. In addition, Sunday is in all white robes, and Gregory in all black.

- Sunday encourages the members of his organization to dress the part of the stereotypical morning-coated, top hat-wearing gentleman, an aversion of the stereotypical caricature of the Bomb Throwing Anarchist. However:

- This is subverted by Tuesday, who normally does dress as the caricature and is uncomfortable in gentleman's clothes, and doubly subverted when that costume is revealed to be itself an assumed role.

- More profoundly, it is subverted by the explicit statement that the real anarchists are the rich aristocrats, the sort of men who do wear top hats and evening dress.

- Subverted again late in the novel, during the chapter "The Earth In Anarchy".

- And again when it's revealed that nobody was actually an anarchist, but were only trying to nab the people who they thought were anarchists - who also weren't anarchists.

- Sunday encourages the members of his organization to dress the part of the stereotypical morning-coated, top hat-wearing gentleman, an aversion of the stereotypical caricature of the Bomb Throwing Anarchist. However:

- Duel to the Death: Syme intentionally provokes one with the Marquis de St. Eustache to prevent him from getting to Paris to carry out an assassination. (It's not actually to the death, though.)

- Evil Redhead: Gregory. But not his equally redheaded sister, Rosamond.

"My red hair, like red flames, shall burn up the world ... "

- Flock of Wolves: Used to the point of hilarity, as well as one the novel's major twists.

- Genteel Interbellum Setting

- God: No, Sunday is not He, though it was a popular interpretation. Chesterton Jossed this view by Word of God in the aforementioned Fan Dumb article.

- Further Word of God on the subject, from two different articles:

"...I think you can take him to stand for Nature as distinguished from God. Huge, boisterous, full of vitality, dancing with a hundred legs, bright with the glare of the sun, and at first sight, somewhat regardless of us and our desires."

"But you will note that I hold that when the mask of Nature is lifted you find God behind."

- Happy Ending: Or at least, it appears to be.

- Heroes Want Redheads: Syme is surprised, "but with a curious pleasure," to have Gregory's red-headed sister Rosamond for company after his debate.

- Hidden in Plain Sight

- Honor Before Reason: Why Gregory can't out Syme to the rest of the anarchist assembly and Syme won't go to the police with the whereabouts of the Council of Days, because each made the other swear he wouldn't.

- Incredibly Lame Pun: "He will say in the most exquisite French, 'How are you?' I shall reply in the most exquisite Cockney, 'Oh, just the Syme --'"

- The Infiltration

- It Runs in The Family

- Masquerade Ball: See Dress-Coded for Your Convenience.

- Meaningful Name: Rosamond, whose name is derived from the Latin rosa mundi, or "Rose of the World," one of the many, many titles given to Jesus. Also, the titles for the members of the Council of Days.

- Mind Screw: The story gets progressively Screwier as it goes on, and the ending takes the cake.

- Misery Poker: Between Syme and Sunday at the end. Sunday wins.

- Mistaken for An Imposter: How Wilks got into the Council and the role of Professor De Worms/Friday.

- Mole in Charge: Syme finds himself in this role at first, but it's much more complicated than he expects.

- Motive Rant: Gregory gives one at the climax of the book; it also doubles as a Hannibal Lecture.

- Mutual Masquerade: The secret police force is so secret that none of its agents knows the identity of any of its other agents.

- Nietzsche Wannabe: Professor De Worms, or at least Wilks' impression of him

- Omniscient Council of Vagueness: Subverted, as all the members save Sunday are policemen in disguise.

- Paper-Thin Disguise: See also War On Straw and Crowning Moment of Funny; Gregory's Epic Fail attempts at undercover agent work.

- Refuge in Audacity: Syme's method of getting himself elected to as the new Thursday and baiting the Marquis/Wednesday into their Duel to the Death. See also Beneath Notice.

- The Reveal: Sunday was both the leader of the Council of Days and the "man in the dark room". Also, all the members of the Council of Days were undercover policemen like Syme.

- Reverse Mole: Syme among others.

- Right Hand Versus Left Hand

- Short Title: Long Elaborate Subtitle

- Sinister Shades: Bull wears a pair of smoked spectacles that obscure his eyes to uncanny effect. Without them, his friendly eyes give him away as an agent of law and order, rather than anarchy.

- Wall of Weapons: The corridor leading to the assembly room in the underground anarchist HQ at the beginning of the book is covered with various pistols, rifles, and other weapons. The assembly room proper is lined with bombs.

- War On Straw: Gregory's explanation of his own failed attempts to go undercover:

"The history of the thing might amuse you," he said. "When first I became one of the New Anarchists I tried all kinds of respectable disguises. I dressed up as a bishop. I read up all about bishops in our anarchist pamphlets, in Superstition the Vampire and Priests of Prey. I certainly understood from them that bishops are strange and terrible old men keeping a cruel secret from mankind. I was misinformed. When on my first appearing in episcopal gaiters in a drawing-room I cried out in a voice of thunder, 'Down! down! presumptuous human reason!' they found out in some way that I was not a bishop at all. I was nabbed at once. Then I made up as a millionaire; but I defended Capital with so much intelligence that a fool could see that I was quite poor. Then I tried being a major. Now I am a humanitarian myself, but I have, I hope, enough intellectual breadth to understand the position of those who, like Nietzsche, admire violence -- the proud, mad war of Nature and all that, you know. I threw myself into the major. I drew my sword and waved it constantly. I called out 'Blood!' abstractedly, like a man calling for wine. I often said, 'Let the weak perish; it is the Law.' Well, well, it seems majors don't do this. I was nabbed again."

- Warrior Poet: Syme is a poet, and, judging by his performance in his duel with the Marquis, something of a warrior.

- We Need a Distraction: See Duel to the Death.

- White Sheep

- Witch Hunt: A form of it is seen later in the novel when the now-revealed-as-policemen Council members are pursued across the countryside by a mob of townspeople and men they thought were allies, led by the Secretary/Monday (who is also a policeman), who are under the mistaken impression that they are the anarchists. It gets cleared up by the end of the chapter, though.

- World of Cardboard Speech: Syme gives one at the climax of the book; it also serves as a Shut UP, Hannibal to Gregory's Motive Rant/Hannibal Lecture.

- Eh, that's subjective. I thought that Gregory's Hannibal Lecture was not refuted, given the question that occurs to Syme.

- In turn, I recall Syme's question being answered with another question. And if one knows the reference that that question is making, one should find the answer quite satisfactory. Which of course means, by the nature of the answer, that to many it won't be.

- Eh, that's subjective. I thought that Gregory's Hannibal Lecture was not refuted, given the question that occurs to Syme.