Treaty of Hadiach

The Treaty of Hadiach (Polish: ugoda hadziacka; Ukrainian: гадяцький договір) was a treaty signed on 16 September 1658 in Hadiach (Hadziacz, Hadiacz, Гадяч) between representatives of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (represented by S. Bieniewski and K. Jewłaszewski) and Ukrainian Cossacks (represented by Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky and starshina Yuri Nemyrych, architect of the treaty, and Pavlo Teteria). It was designed to elevate the Cossacks and Ruthenians to the position equal to that of Poland and Lithuania in the Polish–Lithuanian union and in fact transforming the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth into a Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita Trojga Narodów, "Commonwealth of Three Nations").

| Part of a series on |

| Cossacks |

|---|

|

| Cossack hosts |

| Other groups |

| History |

| Cossacks |

| Cossack terms |

Text

The list of points and humble requests that are submitted at his mercy by Serene Hetman of Zaporizhian Host along with the whole Zaporizhian Host and Russian [Ruthenian] people to his royal mercy and the whole Rzecz Pospolita:[1][2]

1. Creation of the Grand Duchy of Ruthenia (Polish: Wielkie Księstwo Ruskie) from Palatinatus Czernihoviensis, Palatinatus Kioviensis and Palatinatus Braclaviensis,[lower-alpha 1] which along with the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania would be part of one and indivisible "Rzecz Pospolita" (Rex Public) in equal rights.[2]

2. The duchy was to be governed by the Hetman of Zaporizhian Host, elected for life from among four candidates that were chosen by all estates of Ukrainian society and confirmed by the King of Poland.[2]

3. In the duchy were to be established local offices in Polish manner.[2]

4. In the duchy were to be restored law and courts as well as the administrative – territorial system of governing that existed prior to 1648.[2]

5. The Grand Duchy of Ruthenia shall not have rights to independent relations with other counties.[2]

6. Individuals of Eastern Orthodox religion shall hold a senatorial seat.[2]

7. It was permitted to establish own printing institutions of money with an image of one common king.[2]

8. Number of own Armed Forces should be accounted for 60,000 of Cossacks and 10,000 of mercenaries.[2]

9. There were to be restored a big landownership, serfdom and all obligatory duties that existed prior to 1648.[2]

10. To the Cossack Estate were guaranteed the old rights and privileges and up to 100 Cossacks from each regiment[lower-alpha 2] on request of the Hetman to be ennobled by the King.[2]

11. On the territory of the Grand Duchy of Ruthenia were to be canceled the 1596 Church Union of Brest,[lower-alpha 3] announced the freedom of Eastern Orthodox and Catholic religions, to the Easter Orthodox metropolitan bishop and 5 other bishops were granted permanent seats in common Senate of the Rzecz Pospolita.[2]

12. Polish and Lithuanian armed forces had no rights to be on the territory of the Grand Duchy of Ruthenia except for emergencies and in such case they would be subordinated to the Hetman.[2]

13. Existence of 2 universities: the Kiev Mohyla Academy was to be granted the same rights as the Jagiellonian University of Cracow and a newly created college with status of university.[2]

14. Nationwide it was permitted to establish colleges and gymnasiums with rights to teach in Latin.[2][lower-alpha 4]

15. Freedom of publishing as long as the published materials would not have personal attacks against the King.[2]

History and importance

Historian Andrew Wilson has called this "one of the great 'What-ifs?' of Ukrainian and East European history", noting that "If it had been successfully implemented, the Commonwealth would finally have become a loose confederation of Poles, Lithuanians and Ruthenians. The missing Ukrainian buffer state would have come into being as the Commonwealth's eastern pillar. Russian expansion might have been checked and Poland spared the agonies of the Partitions or, perhaps just as likely, it might have struggled on longer as the 'Sick man of Europe'" (p. 65).

In spite of considerable Roman Catholic Clergy opposition, the Treaty of Hadiach was approved by Polish king and parliament (Sejm) on 22 May 1659, but with an amended text.[3] The idea of a Ruthenian Duchy within the Commonwealth was completely abandoned.[4] It was a Commonwealth attempt to regain influence over the Ukrainian territories, lost after the series of Cossack uprisings (like the Khmelnytsky Uprising) and growing influence of Muscovy over the Cossacks (like the 1654 Treaty of Pereyaslav).

Hetman Vyhovsky supported the negotiations with the Commonwealth, especially after he suppressed a revolt led by the colonel of Poltava, Martyn Pushkar, and severed relations with Tsardom of Russia for its violations of the Treaty of Pereyaslav of 1654.[5] The Treaty of Hadiach was, however, viewed by many Cossacks as 'too little, too late', and they especially opposed the agreement to return land property to the szlachta. After the 1648 revolt, the Commonwealth was very unpopular with ordinary Cossacks. Rank-and-file Cossacks saw Orthodox Moscow as their natural ally and did not care for alliance with the Commonwealth. Furthermore, Hadiach was too much a deal that merely benefited the elite of the Cossacks—the "starshyna"—who wanted to be recognized as equal to the Polish nobility. Thus, while some Cossacks, among them the hetman Ivan Vyhovsky supported the Commonwealth, many did not, and Cossack unrest continued in Ukraine.[6]

The Commonwealth position was further weakened by a string of losses in the Russo-Polish War (1654–67). The Tsar felt threatened by the Treaty of Hadiach, which weakened his hold on Cossacks. The Russians saw the treaty as an act of war, and even before it was ratified sent an army into Ukraine. Although Polish forces under hetman Stefan Czarniecki dealt defeat to Russian forces at the battle of Polonka, and recaptured Wilno in 1660, lack of other Commonwealth military successes, especially in Ukraine, further undermined Cossack support of the Commonwealth. Vyhovsky's early success at the battle of Konotop in June 1659 was not decisive enough, and was followed by a series of defeats. The Russian garrisons in Ukraine continued to hold out; a Zaporozhian attack on the Crimea forced Vyhovsky's Tatar allies to return home, and unrest broke out in the Poltava region. Finally, several pro-Russian colonels rebelled and accused Vyhovsky of "selling Ukraine out to the Poles."

Unable to continue the war, Vyhovsky resigned in October 1659 and retired to Poland. The situation was further complicated by the Ottoman Empire, which tried to gain control of the disputed region and played all factions against each other. Meanwhile, the Commonwealth was weakened by the rokosz of Jerzy Lubomirski. The treaty was mostly repeated in the 1660 Treaty of Cudnów.

In the end, Russia was victorious, as seen in the 1667 Treaty of Andrusovo and the 1686 Eternal Peace. Ukrainian Cossacks fell under the Russian sphere of influence, with much fewer privileges under the Hetmanate than would have been granted under the treaty of Hadiach. By the end of the 18th century, Cossack political influence has been almost completely destroyed by the Russian Empire.

Second Treaty of Hadiach

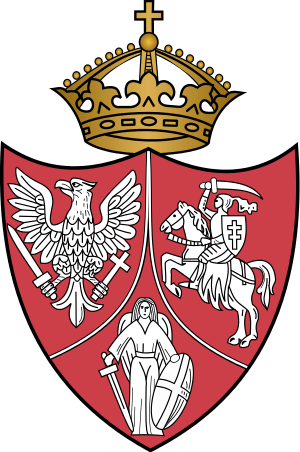

In the aftermath of the November Uprising in 1831, there was an attempt to recreate the Treaty of Hadiach, to form a Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth to throw off the partitions of Poland. It was then that the coat of arms of the proposed Commonwealth was created. The planned convention in Hadiach was declared illegal by the Russians, who stationed close to 2,000 soldiers there to ensure that no meetings or demonstrations take place and blocked passage through nearby bridges. Despite these precautions, a mass and a celebration involving 15–20,000 people and over 200 priests (both Catholic and Orthodox) took place near Hadiach.

Notes

- The Cossack negotiators had originally demanded that Ruthenian Voivodeship, Volhynian Voivodship, Belz Voivodeship, and Podolian Voivodeship be included as well

- there were 16 regiments

- Catholisation

- The official language of the Kingdom of Poland was Latin.

References

- Vyhovsky, I. The list of points and humble requests that are submitted at his mercy by Serene Hetman of Zaporizhian Host along with the whole Zaporizhian Host and Russian [Ruthenian people to his royal mercy and the whole Rzecz Pospolita (ПЕРЕЛІК ПУНКТІВ І ПОКІРНИХ ПРОХАНЬ, ЯКІ ПОДАЄ ЙОГО МИЛІСТЬ ЯСНОВЕЛЬМОЖНИЙ ГЕТЬМАН ВІЙСЬКА ЗАПОРОЗЬКОГО РАЗОМ З УСІМ ВІЙСЬКОМ ЗАПОРОЗЬКИМ І НАРОДОМ РУСЬКИМ ЙОГО КОРОЛІВСЬКІЙ МИЛОСТІ І ВСІЙ РІЧІ ПОСПОЛИТІЙ)]. Izbornik.

- The 1658 treaty of Hadiach (Гадяцький договір 1658 року). Ukrayinskyi istoryk.

- Rober Paul Magocsi "A History of Ukraine" pp.221-225

- Т.Г. Таирова-Яковлева Иван Выговский // Единорогъ. Материалы по военной истории Восточной Европы эпохи Средних веков и Раннего Нового времени, вып.1, М., 2009: Под влиянием польской общественности и сильного диктата Ватикана сейм в мае 1659 г. принял Гадячский договор в более чем урезанном виде. Идея Княжества Руського вообще была уничтожена, равно как и положение о сохранении союза с Москвой. Отменялась и ликвидация унии, равно как и целый ряд других позитивных статей.

- http://www.mfa.gov.ua/rsa/en/20226.htm

- Dvornik, Francis (1962) The Slavs in European History and Civilization. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press

Further reading

- Andrew Wilson, The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation, New Haven: Yale University Press. 2000, review online

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine, University of Washington Press, 1996, ISBN 0-295-97580-6

- Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6. excerpts online