Third Punic War

The Third Punic War (Latin: Tertium Bellum Punicum) (149–146 BC) was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between the former Phoenician colony of Carthage and the Roman Republic. This war was a much smaller engagement than the two previous Punic Wars and focused on Tunisia, mainly on the Siege of Carthage, which resulted in the complete destruction of the city, the annexation of all remaining Carthaginian territory by Rome, and the death or enslavement of the entire Carthaginian population.

| Third Punic War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Punic Wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rome | Carthage | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Scipio Aemilianus Manius Manilius Lucius Marcius Censorinus Calpurnius Piso |

Hasdrubal Himilco Phameas Bythias Diogenes | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

80,000 infantry 4,000 cavalry | 30,000 soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Over 650,000 killed, including civilians 50,000 survivors enslaved | |||||||

Primary sources

The main source for almost every aspect of the Third Punic War[note 1] is the historian Polybius (c. 200 – c. 118 BC), a Greek sent to Rome in 167 BC as a hostage.[2] His works include a now-lost manual on military tactics,[3] but he is now known for The Histories, written sometime after 146 BC.[4][5] Polybius's work is considered broadly objective and largely neutral as between Carthaginian and Roman points of view.[6][7] Polybius was an analytical historian and wherever possible personally interviewed participants, from both sides, in the events he wrote about.[8][9][10] He accompanied the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus during his campaign in North Africa which resulted in the storming of Carhage and Roman victory in the war.[11]

The accuracy of Polybius's account has been much debated over the past 150 years, but the modern consensus is to accept it largely at face value, and the details of the war in modern sources are largely based on interpretations of Polybius's account.[2][12][13] The modern historian Andrew Curry sees Polybius as being "fairly reliable";[14] while Craige Champion describes him as "a remarkably well-informed, industrious, and insightful historian".[15]

Other, later, ancient histories of the war exist, although often in fragmentary or summary form.[16] Appian's account of the Third Punic War is especially valuable.[17] Modern historians usually also take into account the writings of various Roman annalists, some contemporary; the Sicilian Greek Diodorus Siculus; the later Roman historians Livy (who relied heavily on Polybius[18]), Plutarch and Dio Cassius.[19] The classicist Adrian Goldsworthy states "Polybius' account is usually to be preferred when it differs with any of our other accounts".[note 2][9] Other sources include coins, inscriptions, archaeological evidence and empirical evidence from reconstructions such as the trireme Olympias.[20]

Background

Carthage and Rome fought the 17-year-long Second Punic War between 218 and 201 BC which ended with a Roman victory. The peace treaty imposed on the Carthaginians stripped them of all of their overseas territories, and some of their African ones. An indemnity of 10,000 silver talents[note 3][note 4] was to be paid over 50 years. Hostages were taken. Carthage was forbidden to possess war elephants and its fleet was restricted to 10 warships. It was prohibited from waging war outside Africa, and in Africa only with Rome's express permission. Many senior Carthaginians wanted to reject it, but Hannibal spoke strongly in its favour and it was accepted in spring 201 BC.[23][24] Henceforth it was clear that Carthage was politically subordinate to Rome.

At the end of the war the Roman ally Masinissa emerged as by far the most powerful ruler among the Numidians.[25] Over the following 48 years he repeatedly took advantage of Carthage's inability to protect its possessions. Whenever Carthage petioned Rome for redress, or permission to take military action, Rome backed its ally, Masinissa, and refused.[26] Masinissa's seizures of and raids into Carthaginian territory became increasingly flagrant. In 151 BC Carthage raised a large army commanded by Hasdrubal and, the treaty notwithstanding, counter attacked the Numidians. The campaign ended in disaster and the army surrendered[27] and was then massacred.[28] Hasdrubal escaped to Carthage, where in an attempt to placate Rome he was condemned to death.[29] Carthage had paid off its indemnity and was prospering economically, but was no military threat to Rome.[30][31] Elements in the Roman Senate had long wished to destroy Carthage, and with the breach of the treaty as a casus belli, war was declared in 149 BC.[27]

Opposing forces

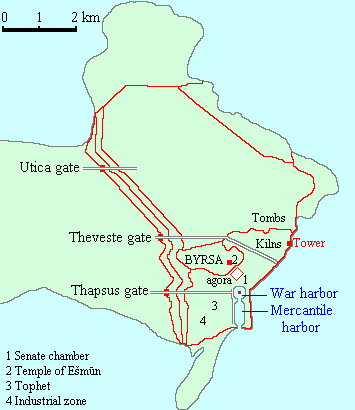

The city of Carthage itself was an unusually large city for the time, with a population estimated at 700,000[32]. It was strongly fortified with walls of more than 35 kilometres (20 mi) circumference.[33] Defending the main approach from the land were three lines of defences, of which the strongest was a wall 9 metres (30 ft) wide and 15–20 metres (50–70 ft) high with a 20-metre -wide (70 ft) ditch in front of it. Built into this wall was a barracks capable of holding over 24,000 soldiers.[34] The city had few reliable sources of ground water, but possessed a complex system to catch and channel rainwater and a large number of cisterns to store it.[35]

The Carthaginians raised a strong and enthusiastic force to garrison the city from their citizenry and by freeing all slaves willing to fight.[36][37] They also formed a 30,000 strong field army, which was placed under Hasdrubal, freshly released from his condemned cell. This army was based at Nepheris, 25 kilometres (16 mi) south of the city.[38] Appian gives the strength of the Roman army which landed in Africa as 84,000 soldiers; modern historians estimate it at 40,000–50,000 men, of which 4,000 were cavalry.[34][39]

Course of the war

The Carthaginians made a series of attempts to appease Rome, and received a promise that if three hundred children of well-born Carthaginians were sent as hostages to Rome the Carthaginians would keep the rights to their land and self-government. Even after this was done the allied Punic city of Utica defected to Rome, and a Roman army of 80,000 men gathered there.[40] The consuls then demanded that Carthage hand over all weapons and armor. After those had been handed over, Rome additionally demanded that the Carthaginians move at least 16 kilometres inland, while the city was to be burned. When the Carthaginians learned of this, they abandoned negotiations and the city was immediately besieged, beginning the Third Punic War.

After the main Roman expedition landed at Utica, consuls Manius Manilius and Lucius Marcius Censorius launched a two-pronged attack on Carthage, but were eventually repulsed by the army of the Carthaginian Generals Hasdrubal the Boeotarch and Himilco Phameas. Censorius lost more than 500 men when they were surprised by the Carthaginian cavalry while collecting timber around the Lake of Tunis.[41] A worse disaster fell upon the Romans when their fleet was set ablaze by fire ships which the Carthaginians released upwind.[42] Manilius was replaced by consul Calpurnius Piso Caesonius in 149 after a severe defeat of the Roman army at Nepheris, a Carthaginian stronghold south of the city. Scipio Aemilianus's intervention saved four cohorts trapped in a ravine.[43] Nepheris eventually fell to Scipio in the winter of 147–146.[44] In the autumn of 148, Piso was beaten back while attempting to storm the city of Aspis, near Cape Bon. Undeterred, he laid siege to the town of Hippagreta in the north, but his army was unable to defeat the Punics there before winter and had to retreat.[45] When news of these setbacks reached Rome, he was replaced as consul by Scipio Aemilianus.[46]

Scipio moved back to a close blockade of the city, and built a mole which cut off supply from the sea.[47] In the spring of 146 BC the Roman army managed to secure a foothold on the fortifications near the harbour.[48][49] When the main assault began it quickly captured the city's main square, where the legions camped overnight.[50] The next morning the Romans systematically worked their way through the residential part of the city, killing everyone they encountered and firing the buildings behind them.[48] At times the Romans progressed from rooftop to rooftop, to prevent missiles being hurled down on them.[50] It took six days to clear the city of resistance, and on the last day Scipio agreed to accept prisoners. The last holdouts, including Roman deserters in Carthaginian service, fought on from the Temple of Eshmoun and burnt it down around themselves when all hope was gone.[51] There were 50,000 Carthaginian prisoners, a small proportion of the pre-war population, who were sold into slavery.[52] The notion that Roman forces then sowed the city with salt is a 19th-century invention.[53][54]

Aftermath

The remaining Carthaginian territories were annexed by Rome and reconstituted to become the Roman province of Africa with Utica as its capital.[55][56] The province became a major source of grain and other foodstuffs.[57] Numerous large Punic cities, such as those in Mauretania, were taken over by the Romans,[58] although they were permitted to retain their Punic system of government.[59] A century later, the site of Carthage was rebuilt as a Roman city by Julius Caesar, and would become one of the main cities of Roman Africa by the time of the Empire.[60][61] The Punic language continued to be spoken in north Africa until the 7th century.[62][63]

Rome still exists as the capital of Italy; the ruins of Carthage lie 16 kilometres (10 mi) east of modern Tunis on the North African coast.[64] A formal peace treaty was signed by Ugo Vetere and Chedli Klibi, the mayors of Rome and the modern city of Carthage, respectively, on 5 February 1985; 2,131 years after the war ended.[65]

Ruins of Carthage

Ruins of Carthage Ruins of Carthage

Ruins of Carthage Ruins of Carthage

Ruins of Carthage

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

- The term Punic comes from the Latin word Punicus (or Poenicus), meaning "Carthaginian", and is a reference to the Carthaginians' Phoenician ancestry.[1]

- Sources other than Polybius are discussed by Bernard Mineo in "Principal Literary Sources for the Punic Wars (apart from Polybius)".[19]

- 50,000 talents was approximately 1,285,000 kg (1,265 long tons) of silver.[21]

- Several different "talents" are known from antiquity. The ones referred to in this article are all Euboic (or Euboeic) talents, of approximately 26 kilograms (57 lb).[21][22]

Citations

- Sidwell & Jones 1998, p. 16.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 20–21.

- Shutt 1938, p. 53.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 20.

- Walbank 1990, pp. 11–12.

- Lazenby 1996, pp. x–xi.

- Hau 2016, pp. 23–24.

- Shutt 1938, p. 55.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 21.

- Champion 2015, pp. 98, 101.

- Champion 2015, p. 96.

- Lazenby 1996, pp. x–xi, 82–84.

- Tipps 1985, p. 432.

- Curry 2012, p. 34.

- Champion 2015, p. 102.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 21–23.

- Le Bohec 2015, p. 430.

- Champion 2015, p. 95.

- Mineo 2015, pp. 111–127.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 23, 98.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 158.

- Scullard 2006, p. 565.

- Miles 2011, p. 317.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 308–309.

- Kunze 2015, p. 398.

- Kunze 2015, pp. 398, 407.

- Kunze 2015, p. 407.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 307.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 308.

- Kunze 2015, p. 408.

- Le Bohec 2015, p. 434.

- Miles 2011, p. 342.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 313.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 340.

- Miles 2011, pp. 342–343.

- Le Bohec 2015, p. 438–439.

- Miles 2011, p. 343.

- Le Bohec 2015, p. 439.

- Le Bohec 2015, p. 436.

- Scullard, pp. 310, 316

- Appian, Punica Archived 2011-09-19 at the Wayback Machine 97–99

- Appian, Punica Archived 2011-09-19 at the Wayback Machine 99

- Appian, Punica Archived 2011-09-19 at the Wayback Machine 102–105

- Appian, Punica Archived 2012-01-12 at the Wayback Machine 126–130

- Appian, Punica Archived 2012-10-19 at the Wayback Machine 110

- Appian, Punica Archived 2011-12-12 at the Wayback Machine 112

- Miles 2011, p. 2.

- Le Bohec 2015, p. 441.

- Miles 2011, p. 346.

- Miles 2011, p. 3.

- Miles 2011, pp. 3–4.

- Scullard 2002, p. 316.

- Ridley 1986, pp. 144–145.

- Ripley & Dana 1858–1863, p. 497.

- Scullard 1955, p. 103.

- Scullard 2002, pp. 310, 316.

- Whittaker 1996, p. 596.

- Pollard 2015, p. 249.

- Fantar 2015, pp. 455–456.

- Richardson 2015, pp. 480–481.

- Miles 2011, pp. 363–364.

- Jouhaud 1968, p. 22.

- Scullard 1955, p. 105.

- UNESCO 2020.

- Fakhri 1985.

Sources

- Bagnall, Nigel (1999). The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6608-4.

- Le Bohec, Yann (2015) [2011]. "The "Third Punic War": The Siege of Carthage (148–146 BC)". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 430–446. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Champion, Craige B. (2015) [2011]. "Polybius and the Punic Wars". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 95–110. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Curry, Andrew (2012). "The Weapon That Changed History". Archaeology. 65 (1): 32–37. JSTOR 41780760.

- Fakhri, Habib (1985). "Rome and Carthage Sign Peace Treaty Ending Punic Wars After 2,131 Years". AP News. Associated Press. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Fantar, M’hamed-Hassine (2015) [2011]. "Death and Transfiguration: Punic Culture after 146". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 449–466. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-304-36642-2.

- Hau, Lisa (2016). Moral History from Herodotus to Diodorus Siculus. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-1107-3.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015b). Mastering the West: Rome and Carthage at War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-986010-4.

- Jouhaud, Edmond Jules René (1968). Historie de lA̕frique du Nord (in French). Éditions des Deux Cogs dÓr.

- Kunze, Claudia (2015) [2011]. "Carthage and Numidia, 201–149". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 395–411. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Lazenby, John (1996). The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2673-3.

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must be Destroyed. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101809-6.

- Mineo, Bernard (2015) [2011]. "Principal Literary Sources for the Punic Wars (apart from Polybius)". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 111–128. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Pollard, Elizabeth (2015). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-92207-3.

- Richardson, John (2015) [2011]. "Spain, Africa, and Rome after Carthage". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 467–482. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Ridley, Ronald (1986). "To Be Taken with a Pinch of Salt: The Destruction of Carthage". Classical Philology. 81 (2): 140–146. JSTOR 269786.

- Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A. (1858–1863). "Carthage". The New American Cyclopædia: a Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge. 4. New York: D. Appleton. p. 497. OCLC 1173144180. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- Scullard, Howard (1955). "Carthage". Greece & Rome. 2 (3): 98–107. JSTOR 641578.

- Shutt, Rowland (1938). "Polybius: A Sketch". Greece & Rome. 8 (22): 50–57. doi:10.1017/S001738350000588X. JSTOR 642112.

- Sidwell, Keith C.; Jones, Peter V. (1998). The World of Rome: an Introduction to Roman Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38600-5.

- Scullard, Howard H. (2002). A History of the Roman World, 753 to 146 BC. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30504-4.

- Scullard, Howard H. (2006) [1989]. "Carthage and Rome". In Walbank, F. W.; Astin, A. E.; Frederiksen, M. W. & Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 7, Part 2, 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 486–569. ISBN 978-0-521-23446-7.

- Tipps, G.K. (1985). "The Battle of Ecnomus". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 34 (4): 432–465. JSTOR 4435938.

- "Archaeological Site of Carthage". UNESCO. UNESCO. 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Walbank, F.W. (1990). Polybius. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06981-7.

- Whittaker, C. R. (1996). "Roman Africa: Augustus to Vespasian". In Bowman, A.; Champlin, E.; Lintott, A. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. X. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 595–96. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521264303.022. ISBN 9781139054386.

Further reading

- Baronowski, Donald Walter. 1995. "Polybius on the causes of the Third Punic War." Classical Philology 90(1): 16–31.

- Purcell, Nicholas. 1995. "On the sacking of Carthage and Corinth." In Ethics and rhetoric: Classical essays for Donald Russell on his seventy fifth birthday. Edited by Doreen Innes, Harry Hine, and Christopher Pelling, 133–48. Oxford: Clarendon.

External links

| Library resources about Third Punic War |

- Delenda est Carthago

- Appian of Alexandria, The Punic Wars, "The Third Punic War"