The Man Who Sold the World (album)

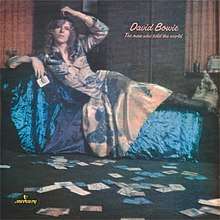

The Man Who Sold the World is the third studio album by English rock singer-songwriter David Bowie. It was originally released by Mercury Records in the United States in November 1970, and in the United Kingdom in April 1971, with different artwork. The album was reissued by RCA Records in 1972, featuring a black-and-white picture of Bowie's then-current character Ziggy Stardust on the front and back covers, but subsequent reissues since 1990 have used the original UK cover as the official artwork.

| The Man Who Sold the World | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

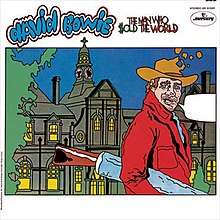

Original 1970 American release | ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 4 November 1970 | |||

| Recorded | 17 April – 22 May 1970 | |||

| Studio | Trident, London; Advision, West London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 40:29 | |||

| Label | Mercury | |||

| Producer | Tony Visconti | |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| David Bowie studio albums chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Alternative cover | ||||

1971 British release | ||||

The album was produced by Tony Visconti and recorded at Trident Studios and Advision Studios in London. Following the largely acoustic and folk rock sound of Bowie's previous 1969 self-titled album, The Man Who Sold the World marked a shift toward hard rock. The lyrics are also darker than his previous releases, exploring themes of insanity, religion, technology and war. None of the songs from the album were released as official singles, although some tracks appeared as B-sides to other songs between 1970 and 1973.

Upon release, The Man Who Sold the World performed well critically and commercially in the US but not as well in the UK. Retrospectively, the album has been praised for the band's performance and the unsettling nature of its music and lyrics. Multiple critics have since considered the album to be the start of Bowie's "classic period". The album has since been remastered in 1999 and in 2015 as part of the box set Five Years (1969–1973).

Background

David Bowie's breakthrough single "Space Oddity" was released in July 1969, bringing Bowie commercial success and attention.[1] However, its parent album, David Bowie (Space Oddity), was not as successful, partly due to the failure of Philips Records to promote the album efficiently.[2] By 1970, the attention Bowie had garnered from "Space Oddity" had dropped and his follow-up single, "The Prettiest Star", which featured Marc Bolan on guitar,[3] failed to chart.[4] Realising that his potential as a solo artist was dwindling, Bowie decided to form a band with bassist Tony Visconti, who previously worked with Bowie on Space Oddity,[5] and drummer John Cambridge. Calling themselves Hype, the group still needed a guitarist.[6]

– David Bowie discussing Woody Woodmansey, 1994

On 2 February 1970, Bowie met guitarist Mick Ronson following a performance at the Marquee in London. The two connected immediately and agreed to work together.[8] Following their meeting, Ronson joined Hype. For their performances, the members wore flamboyant superhero-like costumes, made by Bowie's first wife Angela Burnett, who he married on 20 March,[9] and Visconti's then-girlfriend Liz Hartley. Bowie was Rainbowman (wearing a rainbow-coloured outfit), Ronson was Gangsterman (wearing a "sharp double-breasted suit"), Visconti was Hypeman (sporting a Superman-like outfit was a giant 'H' on the chest), and Cambridge was Cowboyman (wearing a "frilly" shirt and overlarge hat).[10] Hype continued performing in the outlandish costumes for many months; after one performance on 11 March, Visconti's clothes were stolen and he had to return home wearing his Hypeman costume.[11] Bowie halted Hype performances at the end of March so he could focus on recording and songwriting, as well as resolve managing disputes with his manager Kenneth Pitt.[12] The new single version of the Space Oddity track "Memory of a Free Festival" and an early attempt at "The Supermen" were recorded during this time.[13]

Cambridge was dismissed from Hype at the end of March, with a new drummer, Woody Woodmansey, joining the group at the suggestion of Ronson.[7][14] According to biographer Kevin Cann, Cambridge was dismissed by Bowie but according to biographer Nicholas Pegg, Visconti recalled that it was Ronson's request.[7][4] On his first impression of Bowie, Woodmansey said in 2015: "This guy was living and breathing being a rock & roll star."[15] By April 1970, the four members of Hype were living in Haddon Hall, Beckenham, an Edwardian mansion converted to a block of flats that was described by one visitor as having an ambiance "like Dracula's living room".[16] Ronson and Visconti had built a makeshift studio under the grand staircase at Haddon, where Bowie recorded much of his early 1970s demos.[4]

Recording

Recording for The Man Who Sold the World began on 17 April 1970 at Advision Studios in London, with the group beginning work on "All the Madmen". The next day on 18 April, Ralph Mace was hired to play the Moog synthesiser, borrowed from George Harrison,[17] following his work on the single version of "Memory of a Free Festival".[18] Mace was a 40-year-old concert pianist who was also head of the classical music department at Mercury Records.[17] During this time, Bowie terminated his contract with his manager Kenneth Pitt and met his future manager Tony Defries, who assisted Bowie in the termination.[19] Recording moved to Trident Studios in London on 21 April and continued there for the rest of April until mid-May. On 4 May, the group recorded "Running Gun Blues" and "Saviour Machine", the latter of which was originally the working title for the title track, before Bowie reworked the song into a different melody to form the final version of "Saviour Machine". Recording and mixing was moved back to Advision on 12 May and completed on 22 May.[20] Bowie recorded his vocal for the title track on the final day; at this point, he had intended to title the album Metrobolist, a homage to Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis.[21][22]

As Bowie was preoccupied with his new wife Angie at the time, as well as his managerial issues,[23] the music was largely arranged by Ronson and Visconti.[24] Ronson used the sessions to learn about many production and arrangement techniques from Visconti.[25] Although Bowie is officially credited as the composer of all music on the album, biographer Peter Doggett quoted Visconti saying "the songs were written by all four of us. We'd jam in a basement, and Bowie would just say whether he liked them or not." In Doggett's narrative, "The band (sometimes with Bowie contributing guitar, sometimes not) would record an instrumental track, which might or might not be based upon an original Bowie idea. Then, at the last possible moment, Bowie would reluctantly uncurl himself from the sofa on which he was lounging with his wife, and dash off a set of lyrics."[26] Conversely, Bowie was quoted in a 1998 interview as saying "I really did object to the impression that I did not write the songs on The Man Who Sold the World. You only have to check out the chord changes. No-one writes chord changes like that". "The Width of a Circle" and "The Supermen", for example, were already in existence before the sessions began.[27]

Music and lyrics

– David Bowie in an interview with Mojo

The Man Who Sold the World was a departure from the largely acoustic music of Bowie's second album.[29] According to music critic Greg Kot, it marked Bowie's change of direction into hard rock.[30] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic describes the album as "almost all hard blues rock or psychedelic folk rock", while Doggett writes that the album is "filled with propulsive hard rock".[31][32] Much of the album has a distinct heavy metal edge that distinguishes it from Bowie's other releases, and has been compared to contemporary acts such as Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath.[33][34] According to Spitz, Ronson was intent on making a heavy blues albums "worthy of Cream."[23]

Like the music, the album's lyrics are significantly darker than its predecessor. According to Doggett, the album contains numerous themes that Bowie would continue to explore throughout the rest of the decade, including "madness, alienation, violence, confusion of identity, power, darkness and sexual possession."[35] The album has also been seen as reflecting the influence of such figures as Aleister Crowley, Franz Kafka and Friedrich Nietzsche.[36] Since Bowie wrote most of the lyrics at the last minute, O'Leary writes that The Man Who Sold the World is a more "coherent" concept album than Ziggy Stardust and Diamond Dogs. He continues that the songs "mirror and answer each other", sharing similar themes and imagery.[37]

- Side one

The opening track, "The Width of a Circle", is an epic 8-minute track that delves into progressive rock.[15][25] Originally debuted in February 1970 at a BBC session,[38] the song is led by Ronson's widely lauded guitar work,[39] using feedback and improvisation throughout.[40][41] The lyrics reference the Lebanese poet Khalil Gibran and in the song's second half, the narrator has a sexual encounter with God in the devil's lair.[42][43][44] Pegg describes the song's sound as reminiscent of Deep Purple and Black Sabbath.[45] The lyrics of "All the Madmen" were inspired by Bowie's half-brother Terry Burns and reflect the theme of institutionalised madness. It contains a recorder part that creates an atmosphere that Buckley describes as "childlike dementia".[46] Doggett describes the Moog synthesiser as an integral part of the recording, giving it a "stunning conclusion".[47] Spitz calls the track "terrifying".[25]

For "Black Country Rock", Bowie had a small portion of the melody and four quickly-written lines that he gave to Ronson and Visconti, who expanded upon them to create the song.[48][49] A blues-rock and hard rock song,[50][3] Bowie impersonates Marc Bolan in his vocal performance.[51] "After All" is musically different than the rest of the album, being more akin to folk rock than hard rock.[52] Featuring an "oh, by jingo" chant that is reminiscent of music hall numbers,[40][51] the lyrics follow a group of innocent children who have not experienced the corruptions of adulthood.[53] Similar to "The Supermen", it references the works of Friedrich Nietzsche and has been described by Buckley and Pegg as an underrated gem.[40][54]

- Side two

The lyrics of "Running Gun Blues" discuss gun-toting assassins and Vietnam War commentary,[33] specifically the 1968 My Lai Massacre.[55] Although the lyrics reflect the themes of Space Oddity, the music reflects the predominant hard rock style of the album and points to Bowie's future musical direction.[56][57] Similar to the previous track, "Saviour Machine" is rooted in blues rock and hard rock. The lyrics explore the concept of computers overtaking the human race;[58] Bowie's metallic-like vocal performance enhances this scenario.[59][48] O'Leary and Pegg compare the themes to the stories of Patrick Troughton and Jon Pertwee's Doctors in the BBC television programme Doctor Who.[60][61] Like most of the tracks, "She Shook Me Cold" was mostly created by Ronson, Visconti and Woodmansey without Bowie's input.[26] Spitz compares the song's blues style to Led Zeppelin,[51] while O'Leary and Pegg write that Ronson was attempting to emulate Cream's Jack Bruce.[62][63] The lyric explores a sexual conquest that is similar to "You Shook Me" (then-recently covered by Jeff Beck) and Robert Johnson's "Love in Vain".[63][64]

The album's title track has been described by multiple reviewers as "haunting".[15][65][66] Musically, it is based around a "circular" guitar riff from Ronson. Its lyrics are cryptic and evocative, being inspired by numerous poems, including "Antigonish" by William Hughes Mearns.[22][67] The song's narrator has an encounter with a kind of doppelgänger, as suggested in the second chorus where "I never lost control" is replaced with "We never lost control".[68] Bowie's vocals are heavily "phased" throughout and contain none of the, in Doggett's words, "metallic theatrics" that are found on the rest of the album.[66] The song also features guiro percussion, which Pegg describes as "sinister".[22] "The Supermen" prominently reflects the themes of Friedrich Nietzsche, particularly his theory of Übermensch, or "Supermen".[69][70] Like other tracks on the album, the song is predominantly hard rock.[71] It was described by Bowie in 1973 as a "period piece" and later "pre-fascist".[69]

Cover artwork

The original 1970 US release of The Man Who Sold the World employed a cartoon-like cover drawing by Bowie's friend Michael J. Weller, featuring a cowboy in front of the Cane Hill mental asylum.[72] Weller, whose friend was a patient there, suggested the idea after Bowie had asked him to create a design that would capture the music's foreboding tone. Drawing on pop art styles, he depicted a dreary main entrance block to the hospital with a damaged clock tower. For the design's foreground, he used a photograph of John Wayne to draw a cowboy figure wearing a ten-gallon hat and holding a rifle, which was meant as an allusion to the song "Running Gun Blues". Bowie suggested Weller incorporate the "exploding head" signature on the cowboy's hat, a feature he had previously used on his posters while a part of the Arts Lab. He also added an empty speech balloon for the cowboy figure, which was intended to have the line "roll up your sleeves and show us your arms"—a pun on record players, guns, and drug use—but Mercury found the idea too risqué and the balloon was left blank. According to Bowie biographer Nicholas Pegg, "at this point, David's intention was to call the album Metrobolist, a play on Fritz Lang's Metropolis; the title would remain on the tape boxes even after Mercury had released the LP in America as The Man Who Sold the World."[24]

Bowie was enthusiastic about the finished design, but soon reconsidered the idea and had the art department at Philips Records, a subsidiary of Mercury, enlist photographer Keith MacMillan to shoot an alternate cover. The shoot took place in a "domestic environment" of the Haddon Hall living room, where Bowie reclined on a chaise longue in a cream and blue satin "man's dress", an early indication of his interest in exploiting his androgynous appearance.[24] The dress was designed by British fashion designer Michael Fish.[73] It has been said that his "bleached blond locks, falling below shoulder level" in the photo, were inspired by a Pre-Raphaelite painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.[74] In the United States, Mercury rejected MacMillan's photo and released the album with Weller's design as its cover, much to the displeasure of Bowie, although he successfully lobbied the label to use the photo for the record's release in the United Kingdom. In 1972, he said Weller's design was "horrible" but reappraised it in 1999, saying he "actually thought the cartoon cover was really cool".[24]

While promoting The Man Who Sold the World in the US, Bowie wore the Fish dress in February 1971 on his first promotional tour and during interviews, despite the fact that the Americans had no knowledge of the as yet unreleased UK cover.[73] The 1971 German release presented a winged hybrid creature with Bowie's head and a hand for a body, preparing to flick the Earth away. The 1972 worldwide reissue by RCA Records used a black-and-white picture of Ziggy Stardust on the sleeve. This image remained the cover art on reissues until 1990, when the Rykodisc release reinstated the UK "dress" cover. The "dress" cover has appeared on subsequent reissues of the album.[75]

Release

The Man Who Sold the World was released in the US by Mercury Records on 4 November 1970,[76] with the catalogue number SR-61325.[77] It was subsequently released in the UK on 10 April 1971 by Mercury, with the catalogue number 6338 041.[78][79] Bowie was initially aggravated that Mercury had retitled the album from his preferred title Metrobolist without his consultation, but following its release in the US, Bowie attempted to persuade the label to retitle the album Holy Holy (after his newly released single of the same name). Following the commercial flop of "Holy Holy", the title remained The Man Who Sold the World for the UK release.[80] According to Cann, the album was disliked by Mercury executives. However, it was played on US radio stations frequently and its "heavy rock content" increased interest in Bowie. Cann also writes that it developed an underground following and laid "solid foundations" for The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.[81]

None of the songs from the album were released as singles at the time, although a promo version of "All the Madmen" was issued in the US in 1970. Mercury Records released "All the Madmen" as a single, with "Janine" (from the previous album) on the B-side (Mercury 73173), but withdrew it.[82] The same song appeared in Eastern Europe in 1973, as did "The Width of a Circle". "Black Country Rock" was released as the B-side of "Holy Holy" in the UK in January 1971, shortly before the album.[83] The title track appeared as the B-side of both the US single release of "Space Oddity" in 1972 and the UK release of "Life on Mars?" in 1973.[84] The title track also provided an unlikely hit for Scottish pop singer Lulu (produced by Bowie and Ronson)[84] and would be covered by many artists over the years, including Richard Barone in 1987, and Nirvana in 1993, who performed a widely popular cover of "The Man Who Sold the World" for MTV Unplugged in New York.[85]

Commercial performance

The Man Who Sold the World was initially a commercial failure. Pegg writes that by the end of June 1971, the album had sold only 1,395 copies in the US.[86] The same year, Bowie stated: "[it] sold like hotcakes in Beckenham, and nowhere else."[15] However, following a 1972 reissue by RCA after the commercial breakthrough of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars,[87] the album peaked at number 24 on the UK Albums Chart, where it remained for 30 weeks, and number 105 on the US Billboard 200, spending 23 weeks on the chart.[88][89] The album's 1990 reissue charted again on the UK Albums Chart, peaking at number 66.[88]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Music Story | |

| MusicHound Rock | 4/5[91] |

| Pitchfork | 8.5/10[92] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 5/10[91] |

Upon release, The Man Who Sold the World was generally more well-received critically in the US than in the UK.[33] Music publications Melody Maker and NME originally found The Man Who Sold the World "surprisingly excellent" and "rather hysterical", respectively.[96] Reviewing for Rolling Stone in February 1971, John Mendelsohn called the album "uniformly excellent" and commented that producer Tony Visconti's "use of echo, phasing, and other techniques on Bowie's voice ... serves to reinforce the jaggedness of Bowie's words and music", which he interpreted as "oblique and fragmented images that are almost impenetrable separately but which convey with effectiveness an ironic and bitter sense of the world when considered together".[97] Mike Saunders from Who Put the Bomp magazine included The Man Who Sold the World in his ballot of 1971's top-ten albums for the first annual Pazz & Jop poll of American critics, published in The Village Voice in February 1972.[98]

In a retrospective review for AllMusic, senior editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine complimented its "tight, twisted heavy guitar rock that appears simple on the surface but sounds more gnarled upon each listen".[31] Erlewine viewed its music and Bowie's "paranoid futuristic tales" as "bizarre", adding that "Musically, there isn't much innovation ...but there's an unsettling edge to the band's performance, which makes the record one of Bowie's best albums".[31] In a review upon the album's reissue, Q called it "a robust, sexually charged affair",[93] while Mojo wrote, "A robust set that spins with dizzying disorientation ... Bowie's armoury was being hastily assembled, though it was never deployed with such thrilling abandon again".[99] Douglas Wolk of Pitchfork called the album the "dark horse" of Bowie's catalogue. Comparing it to its predecessor, he praised the arrangements as tougher and "more effective" than complimented his artistic growth.[92]

Aftermath and legacy

After Bowie completed the album, he became less active in both the studio and on stage. This was partly due to challenges that his new manager Tony Defries faced.[100][101] After hearing Bowie's new single "Holy Holy", which he recorded in November 1970,[102] Defries signed Bowie to a contract with Chrysalis, but thereafter limited his work with Bowie to focus on other projects, including an attempt to become American singer-songwriter Stevie Wonder's manager after Wonder's contract ended with Motown Records. Bowie, who was devoting himself to songwriting, turned to Chrysalis partner Bob Grace, who, according to Pegg, had "courted" Bowie on "the strength of 'Holy Holy'", and subsequently booked time at Radio Luxembourg's studios in London for Bowie to record his demos.[100][103] In August 1970, due to his dislike of Defries and his frustration with Bowie's lack of enthusiasm during the making of The Man Who Sold the World, Visconti parted ways with Bowie; it was the last time he would see the artist for three or four years.[104][86] Ronson and Woodmansey, who had never been offered steady pay for their performances, also departed.[104] Visconti went to produce Marc Bolan, while Ronson and Woodmansey returned to Haddon Hall, to form a short-lived group called Ronno with Benny Marshall of the English band the Rats.[86][105] Despite his annoyance with Bowie during the sessions, Visconti still rated The Man Who Sold the World as his best work with Bowie until 1980's Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps).[36]

The Man Who Sold the World has been retrospectively described by Bowie biographers and commentators as the beginning of Bowie's artistic growth, with many also agreeing that it was his first album where he began to find his sound. Author David Buckley has described that record as "the first Bowie album proper."[106] NME critics Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray have said of the album, "this is where the story really starts".[33] Pegg calls The Man Who Sold the World one of the best and important albums in the history of rock music.[107] Erlewine cites The Man Who Sold the World as the beginning of Bowie's "classic period".[31] Similarly, Annie Zaleski of The A.V. Club called the album his "career blueprint", writing "Musically, it presages the swaggering electric disorientation of Ziggy Stardust and 1973's Aladdin Sane, but its emphasis on sequencing and mood, as well as deliberate songcraft, informed 1971's Hunky Dory.[3]

The album has since been cited as inspiring the goth rock, dark wave and science fiction elements of work by artists such as Siouxsie and the Banshees, the Cure, Gary Numan, John Foxx and Nine Inch Nails.[36] In his journal, Kurt Cobain of Nirvana listed it at No. 45 in his top 50 favourite albums.[108] In 1993, Nirvana covered its title-track for their televised special MTV Unplugged in New York. It has been claimed that glam rock began with the release of this album,[109] though this is also attributed to Marc Bolan's appearance on the UK TV programme Top of the Pops in December 1970 wearing glitter,[110] to perform what would be his first UK hit single under the name T. Rex, "Ride a White Swan", which peaked at number two in the UK charts.[111]

Reissues

The Man Who Sold the World was first released on CD by RCA in 1984. The German (RCA PD84654, for the European Market) and Japanese (RCA PCD1-4816, for the US market) masters were sourced from different tapes and are not identical for each region. The album was reissued by Rykodisc (RCD 10132)/EMI (CDP 79 1837 2) on 30 January 1990 with an extended track listing, including a 1974 re-recording of Bowie's single "Holy Holy" originally issued as a b-side (but incorrectly identified as the 1971 original). Rykodisc later released this album in the Au20 series (RCD 80132) with 24-bit digitally remastered sound. "Holy Holy" was incorrectly described in the liner notes as the original single version, recorded in November 1970 and released in January 1971. Bowie vetoed inclusion of the earlier recording, and the single remained the only official release of the 1970 recording until 2015, when it was included on Re:Call 1, part of the Five Years (1969–1973) compilation.[112] Similarly, the liner notes incorrectly list the personnel for "Lightning Frightening" as those who played with Bowie during the Space Oddity period, when in fact the personnel were members of the Arnold Corns sessions proto-group.[113]

In 1999, the album was reissued again by Virgin/EMI (7243 521901 0 2), without the bonus tracks but with 24-bit digitally remastered sound. The Japanese mini LP (EMI TOCP-70142) replicates the cover and texture of the original Mercury LP. In 2015, the album was remastered for the Five Years (1969–1973) box set.[112] It was released in CD, vinyl, and digital formats, both as part of this compilation and separately.[114]

Track listing

All tracks written by David Bowie.

- Side one

- "The Width of a Circle" – 8:05

- "All the Madmen" – 5:38

- "Black Country Rock" – 3:32

- "After All" – 3:52

- Side two

- "Running Gun Blues" – 3:11

- "Saviour Machine" – 4:25

- "She Shook Me Cold" – 4:13

- "The Man Who Sold the World" – 3:55

- "The Supermen" – 3:38

- Bonus tracks (1990 Rykodisc/EMI)

- "Lightning Frightening" (1971 outtake from the Arnold Corns sessions) – 3:38

- "Holy Holy" (1974 B-side re-recording of A-side from non-LP single) – 2:20

- "Moonage Daydream" (1971 Arnold Corns version) – 3:52

- "Hang On to Yourself" (1971 Arnold Corns version) – 2:51

Personnel

Adapted from The Man Who Sold the World liner notes.[77]

- David Bowie – vocals, guitars, stylophone, organ, saxophone

- Mick Ronson – guitars, backing vocals

- Tony Visconti – bass guitar, piano, guitar, recorder, producer, backing vocals

- Mick Woodmansey – drums, percussion

- Ralph Mace – Moog synthesiser

- Ken Scott – engineer

Charts

| Chart (1972–73) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Albums Chart[88] | 24 |

| US Billboard 200[89] | 105 |

| Chart (1990) | Peak position |

| UK Albums Chart[88] | 66 |

| Chart (2016) | Peak position |

| Canadian Albums (Billboard)[115] | 62 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[116] | 48 |

| French Albums (SNEP)[117] | 149 |

| Italian Albums (FIMI)[118] | 49 |

| UK Albums Chart[88] | 21 |

| US Top Pop Catalog Albums[119] | 38 |

References

- Pegg 2016, pp. 449, 454.

- Pegg 2016, p. 592.

- Zaleski, Annie (13 January 2016). "On The Man Who Sold The World, David Bowie found his career blueprint". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Pegg 2016, p. 594.

- Pegg 2016, p. 588.

- Stafford, James (4 November 2015). "The Day David Bowie Became David Bowie on 'The Man Who Sold the World'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Cann 2010, p. 189.

- Cann 2010, pp. 180–181.

- Pegg 2016, p. 931.

- Pegg 2016, p. 929.

- Pegg 2016, p. 930.

- Cann 2010, p. 188.

- Cann 2010, pp. 188–190.

- Pegg 2016, p. 932.

- Wolk, Douglas (4 November 2016). "How David Bowie Realized Theatrical Dreams on 'The Man Who Sold the World'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Martin Aston (2007). "Scary Monster", MOJO 60 Years of Bowie: p. 24.

- "Revisiting a Classic: Tony Visconti Talks about Taking David Bowie's The Man Who Sold The World on the Road". www2.gibson.com. 6 May 2015. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Cann 2010, pp. 190–191.

- Cann 2010, p. 191.

- Cann 2010, pp. 191–193.

- Cann 2010, p. 193.

- Pegg 2016, p. 316.

- Spitz 2009, p. 143.

- Pegg 2011, pp. 301–306.

- Spitz 2009, p. 144.

- Doggett 2012, pp. 97–98.

- Pegg 2011, p. 302.

- Spitz 2009, pp. 143–144.

- Perone 2012, p. 90.

- Kot, Greg (10 June 1990). "Bowie's Many Faces Are Profiled On Compact Disc". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Man Who Sold the World – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- Doggett 2012, p. 106.

- Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 37–38.

- Perone 2007, p. 19.

- Doggett 2012, p. 105.

- Buckley 1999, pp. 99–105.

- O'Leary 2015, pp. 193–194.

- Pegg 2016, p. 549.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 183.

- Buckley 2005, p. 85.

- Doggett 2012, p. 88.

- Buckley 2005, p. 86.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 184.

- Martin Aston (2007). "Scary Monster", MOJO 60 Years of Bowie: pp. 24–25

- Pegg 2016, p. 550.

- Buckley 2005, p. 84.

- Doggett 2012, p. 101.

- Doggett 2012, p. 102.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 202.

- Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 36–38.

- Spitz 2009, p. 145.

- Unterberger, Richie. ""After All" – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Doggett 2012, p. 95.

- Pegg 2016, p. 28.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 200.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 405–406.

- Raggett, Ned. ""Running Gun Blues" – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Unterberger, Richie. ""Saviour Machine" – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- O'Leary 2015, pp. 197–198.

- Pegg 2016, p. 410.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 198.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 196.

- Pegg 2016, p. 424.

- Doggett 2012, p. 98.

- Kaufman, Spencer (11 January 2016). "Top 10 David Bowie songs". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Doggett 2012, p. 104.

- Thompson, Dave. ""The Man Who Sold the World" – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- King, Maureen (1997). "Future Legends: David Bowie and Science Fiction". In Morrison, Michael A. (ed.). Trajectories of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Fourteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-313-29646-8.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 187.

- Doggett 2012, p. 91.

- Unterberger, Richie. ""The Supermen" – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- THE CULT OF CANE HILL Archived 2 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Urbex | UK Archived 23 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- Poulsen, Jan (2007) [2006]. David Bowie – Station til station (in Danish) (2nd ed.). Gyldendal. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-87-02-06313-4. Archived from the original on 14 December 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2009. However, see also Spitz, Marc (2010). David Bowie A Biography. London: Aurum. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-84513-551-5.

'In Chicago, New York, he didn't wear any dresses,' [Ron] Oberman says. 'But he wore the dress in L.A.'

(Ron Oberman was then American publicist for Mercury Records). - Jones 1987, p. 197.

- The Man Who Sold The World (2015 reissue) (Media notes). Parlophone. 2015. DB69732.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 560.

- The Man Who Sold the World (liner notes). David Bowie. US: Mercury Records. 1970. SR-61325.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Pegg 2016, p. 593.

- The Man Who Sold the World (liner notes). David Bowie. UK: Mercury Records. 1971. 6338 041.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Pegg 2016, p. 600.

- Cann 2010, p. 211.

- Pegg 2011, pp. 20–21.

- Pegg 2011, p. 40.

- Pegg 2011, p. 159.

- Saunders, Luke. "Here are the 10 best covers of all time from here to eternity". happymag.tv. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Pegg 2016, p. 601.

- Pegg 2011, p. 301.

- "The Man Who Sold the World". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- "The Man Who Sold the World Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Larkin, Colin (2007). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-85712-595-8.

- "The Man Who Sold the World". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Wolk, Douglas (1 October 2015). "David Bowie: Five Years 1969–1973". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- "David Bowie: The Man Who Sold the World (EMI)". Q. EMAP Metro Ltd (158): 140–41. November 1999.

- Sheffield, Rob (2004). "David Bowie". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 97–99. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Dolan, Jon (July 2006). "How to Buy: David Bowie". Spin. 22 (7): 84. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Pegg 2011, p. 306.

- Mendelsohn, John (18 February 1971). "The Man Who Sold The World by David Bowie". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- Christgau, Robert (10 February 1972). "Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- Columnist (February 2002). "David Bowie – The Man Who Sold the World (EMI)". Mojo. EMAP Metro Ltd (99): 84.

- Cann 2010, pp. 195–196.

- Pegg 2016, p. 603.

- Cann 2010, p. 199.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 603–604.

- Cann 2010, p. 197.

- Cann 2010, p. 214.

- Buckley 1999, p. 78.

- Pegg 2016, p. 602.

- "Kurt's Journals – His Top 50 Albums". www.nirvanaclub.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- Bourgoin & Byers 1998, p. 59.

- Bourgoin & Byers 1998, p. 59; Auslander 2006, p. 196

- British Hit Singles & Albums, Guinness World Records

- "Five Years 1969 – 1973 box set due September". David Bowie Official Website. 18 February 2016. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016.

- Pegg 2011, p. 145.

- "David Bowie / 'Five Years' vinyl available separately next month". Super Deluxe Edition. 16 February 2016. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016.

- "David Bowie Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Dutchcharts.nl – David Bowie – The Man Who Sold the World" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Lescharts.com – David Bowie – The Man Who Sold the World". Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Album – Classifica settimanale WK 16 (dal 2016-04-15 al 2016-04-21)" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "The Man Who Sold the World Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

Bibliography

- Auslander, Philip (2006). Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan. ISBN 0-472-06868-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bourgoin, Suzanne M.; Byers, Paula K. (eds.) (1998). Encyclopedia of World biography 18 Supplement: A-Z (2nd ed.). Detroit, London: Gale. ISBN 0-7876-2945-6.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buckley, David (1999). Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-1-85227-784-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-75351-002-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cann, Kevin (2010). Any Day Now – David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974. Croyden, Surrey: Adelita. ISBN 978-0-95520-177-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record. London: Eel Pie Publishing. ISBN 978-0-38077-966-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Mablen (1987). Getting It On: The Clothing of Rock 'n' Roll. New York: Abbeville. p. 197. ISBN 0-89659-686-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Leary, Chris (2015). Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie from '64 to '76. Winchester: Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-78099-244-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perone, James (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27-599245-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perone, James E. (2012). The Album: A Guide to Pop Music's Most Provocative, Influential, and Important Creations. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-313-37906-8. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pegg, Nicholas (2011). The Complete David Bowie (6th ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-0-85768-290-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated Edition). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York, NY: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- The Man Who Sold the World at Discogs (list of releases)