Diamond Dogs

Diamond Dogs is the eighth studio album by English singer-songwriter David Bowie, released on 24 May 1974 by RCA Records. It was produced by Bowie himself and recorded in early 1974 at Olympic and Island Studios in London and Ludolph Studios in the Netherlands, following the disbandment of his backing band the Spiders from Mars, and the departure of producer Ken Scott. Due to the absence of Mick Ronson, Bowie plays guitar himself on the record. The album also featured the return of Tony Visconti, who had not worked with Bowie for four years; the two would collaborate for the rest of the decade. Musically, it was Bowie's final album in the glam rock genre; some of the songs were influenced by soul music, which Bowie embraced for his next album Young Americans.

| Diamond Dogs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 24 May 1974 | |||

| Recorded | January–February 1974 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 38:25 | |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Producer | David Bowie | |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| David Bowie studio albums chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Diamond Dogs | ||||

| ||||

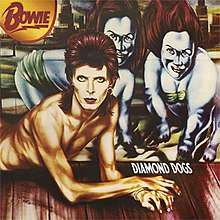

Conceived during a period of uncertainty of where his career was headed, Diamond Dogs is the result of multiple projects Bowie had yet to envision at the time. One of these was an adaptation of George Orwell's 1949 novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. After being denied the rights by Orwell's widow, Bowie conceived a musical based on Ziggy Stardust, which was ultimately scrapped. The final project was an urban apocalyptic scenario based on the writings of William S. Burroughs. Together, the songs from these projects form the theme of the album. Although the title track introduces a new persona named Halloween Jack, Ziggy Stardust is still present throughout the album. The controversial cover artwork, depicting Bowie as a half-man, half-dog hybrid, was painted by Belgian artist Guy Peellaert, based on photos taken of Bowie by photographer Terry O'Neill.

Preceded by the lead single "Rebel Rebel", Diamond Dogs was a commercial success, peaking at No. 1 on the UK Albums Chart and No. 5 on the US Billboard 200. It received mixed reviews from music critics on release and continues to receive mixed reactions, with many criticising its lack of cohesiveness. Nevertheless, it has been considered by Bowie biographers as one of his best works and was ranked as one of the greatest albums of all time by NME in 2013. Bowie supported the album on the Diamond Dogs Tour, which featured elaborate set-pieces and high costs; performances from the tour have been released on two live albums, David Live (1974) and Cracked Actor (2017). The album has retrospectively been seen an influential on the punk revolution that would spawn in the following years. It has been reissued multiple times and was remastered in 2016 as part of the Who Can I Be Now? (1974–1976) box set.

Background

– Ken Scott on his departure with Bowie

By the time Bowie was recording his seventh studio album Pin Ups in the summer of 1973, he was unsure of where to take his career.[2] Not wanting Ziggy Stardust to define him, he disbanded his backing band the Spiders from Mars and producer Ken Scott. Mick Ronson launched a solo career, releasing the albums Slaughter on 10th Avenue (1974) and Play Don't Worry (1975) and worked as a session musician, but would never again reach the popularity and fame he received during his time with Bowie.[3] Trevor Bolder departed to play with Uriah Heep while Woody Woodmansey formed U-Boat and toured with various artists such as Art Garfunkel and Paul McCartney. Scott, who Bowie called his 'George Martin', went to produce Supertramp's Crime of the Century. According to biographer David Buckley, the departure of Scott marked an end to Bowie's "classic 'pop' period" and brought him to more experimental territory and "arguably greater musical daring".[3]

During the Pin Ups sessions, he told reporters that he wanted to create a musical, using various titles such as Tragic Moments and Revenge, or The Best Haircut I Ever Had. His guitarist Mick Ronson recalled: "[Bowie] had all these little projects...[he] wasn't quite sure what he wanted to do."[2] As Ronson began work on Slaughter on 10th Avenue, Bowie and his wife Angie decided to move out of Haddon Hall, due to the beratement of fans. They initially moved into an apartment in Maida Vale, rented to them by actress Diana Rigg, before moving into a larger house at Oakley Street, Chelsea.[2][4] According to Buckley, Bowie's manager Tony Defries initially prevented this move, citing the house as "too extravagant". Despite RCA Records estimating Bowie's album and single sales in the UK at over two million copies combined, Defries stated that sales did not earn Bowie enough income to afford the house.[4] Nevertheless, it was here the Bowies spent time with Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood of the Faces, Mick Jagger and his then-wife Bianca, as well as the 18-year-old American Ava Cherry, who Bowie allegedly had an affair with during this time.[5][6]

Along with recording Pin Ups, Bowie participated in other musical ventures in 1973. He co-produced and played on Lulu's recording of "The Man Who Sold the World", which was released as a single in January 1974,[7][8] contributed to Steeleye Span's Now We Are Six,[5] as well as formed a trio called the Astronettes, comprising Ava Cherry, Jason Guess and Geoff MacCormack.[6] Sessions were conducted for the group at Olympic Studios in London but the project was ultimately shelved in January; a compilation album titled People from Bad Homes (later The Astronettes Sessions) was released in 1995. Songs from these sessions were later reworked by Bowie in subsequent years.[5][lower-alpha 1] Buckley writes that the songs recorded featured a blend of glam rock and soul, which proved to be the direction Bowie took in 1974.[10]

Writing and recording

According to biographer Chris O'Leary, Diamond Dogs is the combination of numerous projects Bowie had yet to envision at the time.[11] One of these was an adaptation of George Orwell's 1949 novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, one of Bowie's favourites.[12] Bowie had wanted to make a theatrical production of the novel and began writing material after completing sessions for Pin Ups, but the author's widow, Sonia Orwell, denied the rights.[13] Bowie was annoyed with the rejection, lambasting her to Circus a few years later. Orwell refused any adaptation of her late husband's work for the rest of her life, with no adaptations becoming possible until after her death in 1980.[5] Another project Bowie envisioned was a Ziggy Stardust musical, stating: "Forty scenes are in it and it would be nice if the characters and actors learned the scenes and we all shuffled them around in a hat the afternoon of the performance and just performed it as the scenes come out."[5] The project fell through, being considered a "retrograde step" according to biographer Nicholas Pegg, but two songs Bowie wrote for it, "Rebel Rebel" and "Rock 'n' Roll with Me", were salvaged for Diamond Dogs.[5] The final project was an urban apocalyptic scenario influenced by the works of writer William S. Burroughs. Songs from this scenario included what would become the title track and "Future Legend".[11][14]

Buckley writes that the album was the first instance of Bowie using the studio as an instrument.[10] With Scott's departure, Bowie produced the album himself and engineering duties were handled by Keith Harwood,[10] who previously working with the Rolling Stones for numerous sessions and on Led Zeppelin's Houses of the Holy.[15] Pegg writes that despite Bowie and Harwood's previous collaborations on Mott the Hoople's All the Young Dudes and the original version of "John, I'm Only Dancing", Diamond Dogs was Harwood's first credit on a Bowie album. Bowie described being "in awe" of Harwood due to his previous credits with the Stones. With the departure of the Spiders from Mars, lead guitar duties were handled by Bowie himself, who recalled in 1997 that he practiced every day as "[he] knew that the guitar playing had to be more than okay".[15] In a move that surprised NME critics Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray, producing what they described as a "scratchy, raucous, semi-amateurish sound that gave the album much of its characteristic flavour".[16] Pianist Mike Garson and drummer Aynsley Dunbar returned from the Pin Ups sessions, Tony Newman also performed drums while Herbie Flowers, who previously played on Space Oddity (1969), was re-recruited to play bass. Alan Parker of Blue Mink played guest guitar on "1984" and "augmented" Bowie's riff on "Rebel Rebel". Bowie's longtime friend Geoff MacCormack, now known as Warren Peace, performed backing vocals.[15][4] Diamond Dogs was also a milestone in Bowie's career as it reunited him with Tony Visconti, who provided string arrangements and helped mix the album at his own studio in London. Visconti would go on to co-produce much of Bowie's work for the rest of the decade.[13]

Before the Nineteen Eighty-Four premise was denied, Bowie worked on "1984" early, recording it on 19 January 1973 during the sessions for Aladdin Sane.[17] Initial work on Diamond Dogs began in late October 1973 at Trident Studios in London. Here, Bowie recorded "1984" in a medley with "Dodo", titled "1984/Dodo", with Scott; following mixing, the session marked the final time the two worked together.[1][5] According to O'Leary, this session also marked Bowie's final performance with Ronson and Bolder.[18] The medley made its public debut on the American television show The 1980 Floor Show, which was recorded in London on 18–20 October 1973.[19] Recording officially commenced for the album at Olympic at the start of 1974. Bowie initially began work on "Rebel Rebel" at a solo session at Trident following Christmas 1973. It would be Bowie's last known visit to Trident, his principal recording studio since 1968.[20] On New Year's Day, the group recorded "Candidate" and "Take It In Right", an early version of "Right" from Young Americans.[21] Following the final sessions with the Astronettes, recording continued from 14–15 January, with the group recording "Rock 'n' Roll with Me", "Candidate", "Big Brother", "Take It In Right" and the title track. The following day, "We Are the Dead" was recorded, after which Bowie contacted Visconti for mixing advice.[21] O'Leary writes that "Rebel Rebel" was finished around this time.[22] Recording was finished at Ludolph Studios in the Netherlands, where the Stones had just finished recording their 1974 album It's Only Rock 'n Roll.[23]

Music and themes

Diamond Dogs was Bowie's final album in the glam rock genre.[24] Buckley writes: "In the sort of move which would come to define his career, Bowie jumped the glam-rock ship just in time, before it drifted into a blank parody of itself".[25] The album has often been regarded as an "English proto-punk" record, according to the cultural studies academic Jon Stratton, who calls it "post-glam".[26] The pop culture scholar Shelton Waldrep describes it as "wonderfully dark proto-punk",[27] while the music journalist C.M. Crockford says it is "the goofy, abrasive place where punk and art-rock meet, dance a little, and depart".[28] In the opinion of The Guardian's Adam Sweeting, while "the music still has one foot in the glam-rock camp", the album marks the point in Bowie's career where he "began exploring a kind of Weimar soul music with lavish theatrical packaging", featuring Broadway-style ballads such as "Big Brother" and "Sweet Thing".[29] Nicholas Pegg describes the album as having "manic alternations between power-charged garage rock and sophisticated, synthesiser-heavy apocalyptic ballads".[24] Biographer Christopher Sandford writes that beyond the overall concept, many of the songs delve into R&B.[30] Barry Walters of Pitchfork writes that although it's still primarily glam rock, it also contains elements of "Blaxploitation funk and soul, rock opera, European art song, and Broadway."[31]

Side one

– David Bowie describing the Diamond Dogs

The opening track, "Future Legend", is a spoken word track that depicts a world ridden by an urban apocalypse. The visions of decay are inspired by the writings of William S. Burroughs, especially The Wild Boys (1971). Author Peter Doggett notes that unlike the opening of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, which announces that the world will end in five years, the apocalypse of "Future Legend" could happen at any time.[14][33][34] Bowie begins the title track by announcing "This ain't rock'n'roll – this is genocide". The track introduces Bowie's newest persona, Halloween Jack, described as "a real cool cat" who "lives on top of Manhattan Chase" in the urban wasteland depicted in "Future Legend".[35] He rules the "diamond dogs", who O'Leary describes as "packs of feral kids camped on high-rise roofs, tearing around on roller skates, terrorizing the corpse-strewn streets they live above."[36] Although Jack is commonly identified as one of Bowie's "identities" with Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane, Doggett notes that Jack occupies "little more than a cameo role."[37] The riff and saxophone are inspired by the Rolling Stones.[32] Bowie's voice is also noticably lower-pitched than his earlier records, which Ned Raggett of AllMusic believes fits the song perfectly.[38] Biographer Marc Spitz notes that it is the same "jaded commentator's voice" Bowie had used on Aladdin Sane.[39]

The suite of "Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (Reprise)" is described by multiple biographers as the album's highlight.[40][41][42] Bowie's vocal performance, which Pegg believes to be one of his finest,[40] is described as a croon.[39][43] "Sweet Thing" paints pictures of decay, with sex being a "drug-like commodity" while "Candidate" contains references to Charles Manson and Muhammad Ali, with Bowie being "consumed by the fakery of his own stage creations".[40] "Rebel Rebel" is based around a distinctive guitar riff reminiscent of the Rolling Stones.[44] Bowie's most-covered track,[45] it was his farewell to the glam rock era.[46] The song features guest guitar from Alan Parker who, according to Pegg, "added the three descending notes at the end of each loop of the riff".[47] It features gender-bending lyrics ("You got your mother in a whirl / She's not sure if you're a boy or a girl").[48] Although Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic praised the song, he felt it did not contribute to the overall theme of the album.[49] Doggett however, writes that the song acts as the "musical continuation" of the "Sweet Thing" suite.[50]

Side two

"Rock 'n' Roll with Me" was co-written by Bowie and Geoff MacCormack, also known as Warren Peace.[51] It was Bowie's first co-writing credit on one of his own albums.[52] MacCormack stated that his contribution was minimal – he played the chord sequence on piano.[53] A power ballad,[54] the song explores the relationship between the audience and actor. When asked about whether fans considered him a leader, Bowie described "Rock 'n' Roll with Me" as his response, stating: "You're doing it to me, stop it!"[55][56] Buckley writes that the song foreshadowed the soul direction that Bowie would take on Young Americans.[53] The lyrics of "We Are the Dead" reflect the characters of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston and Julia's, love for each other. They establish a world fraught with danger that mirrors the rest of the album.[57] Buckley describes the lyrics as "Gothic" and the music as "creepy".[58] Although it directly quotes Nineteen Eighty-Four, O'Leary argues that the song owes more to the writings of Burroughs.[59]

The centrepiece of side two on the original LP, "1984" was the signature number for Bowie's planned adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four.[60] It has been interpreted as representing Winston Smith's imprisonment and interrogation by O'Brien.[19] The lyrics also bear some similarities to Bowie's earlier song "All the Madmen", from The Man Who Sold the World ("They'll split your pretty cranium and fill it full of air").[61] Donald A. Guarisco of AllMusic writes: "Bowie's recording of "1984" fully realizes the song's cinematic potential with a dramatic arrangement that utilizes skittering strings and a throbbing wah-wah guitar line that effectively mirrors the song's clipped, militaristic rhythms."[62] Originally recorded during the Aladdin Sane sessions,[17] the re-recording's wah-wah guitar is reminiscent of Isaac Hayes's "Theme from Shaft".[41][63] Guarisco and Pegg felt the song's funk and soul nature fully predicted Bowie's direction he would take on Young Americans.[60][62]

According to Pegg, the theme of "Big Brother" is "the dangerous charisma of absolute power and the facility with which societies succumb to totalitarianism's final solutions."[64] It was a possible contender to close Bowie's adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four.[65] Featuring synthesisers and saxophones,[64] the track builds to a climax that Buckley considers reminiscent of The Man Who Sold the World.[41] The track segues into "Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family", a variation on "Two Minutes Hate" from Nineteen Eighty-Four.[66][67] It is a chant in 5/4 and 6/4 time, with a distorted guitar loop. On the original LP, the word brother repeats in a "stuck-needle effect", similar to the ending of the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[68]

Artwork and packaging

– Guy Peellaert on doing the cover artwork, 2000

The cover artwork depicts Bowie as a striking half-man, half-dog grotesque. He dons his Ziggy Stardust haircut and is surrounded by two other "freak-show" dogs against a backdrop of New York City.[70][71] The artwork originated from a photo session with photographer Terry O'Neill. Bowie opted to not use any of his previous cover artwork photographers and instead requested the services of Belgian artist Guy Peellaert, whose then-recently published Rock Dreams catalogue, featuring numerous airbrushed and exploited photographs, was rising in popularity. Bowie invited Peellaert to the photoshoot, where Bowie posed as a dog. A Great Dane was brought to the session, which Bowie also posed with.[69][70] Following the session, Bowie asked Peellaert if he would like to develop a painting for the artwork, based on a storyboard idea of Bowie's where he appeared as a half-man, half-dog, and similar to Peelleart's then-concurrent work on the Rolling Stones' album cover for It's Only Rock 'n Roll. Peellaert accepted, basing the backdrop on a book he owned about Coney Island's Pleasure Park. The two dogs behind Bowie were based on the Island's Cavalcade Variety Show performers Alzoria Lewis (known as 'the Turtle Girl') and Johanna Dickens (known as 'the Bear Girl').[69][70]

The artwork was controversial as the full image on the gatefold sleeve showed the hybrid's genitalia. The genitalia were airbrushed out of the original sleeve on most releases by RCA. Some original uncensored copies made their way into circulation at the time of the album's release.[69][70] According to the record-collector publication Goldmine price guides, these albums have been among the most expensive record collectibles of all time, as high as thousands of US dollars for a single copy.[72] Other changes to the artwork included the substitution of the freak show badge 'Alive' with the word 'Bowie'; Bowie was credited simply as 'Bowie', continuing the convention established by Pin Ups.[69][70] Peelaert's original uncensored artwork was restored for the Rykodisc/EMI re-release of the album in 1990, and subsequent reissues have included a rejected inner gatefold image featuring Bowie in a sombrero cordobés holding onto a ravenous dog with a copy of Walter Ross's novel The Immortal, whose protagonist is based on James Dean, at his feet.[69][70]

Release and promotion

The lead single, "Rebel Rebel", was released on 15 February 1974 in the UK by RCA Records (as LPB05009) as the lead single of Diamond Dogs with the Hunky Dory song "Queen Bitch" as the B-side.[73] The same day, Bowie recorded a lip synced performance of "Rebel Rebel" at Hilversum's Avro Studio 2 for the Dutch television programme Top Pop. Transmitted two days later, it featured Bowie donning what Pegg calls his short-lived "pirate image" – an eyepatch and a spotted neckerchief. This costume was changed after the performance, in favour of the "swept-back parting and double-breasted suits" of the Diamond Dogs Tour.[74] The single was a commercial success and quickly became a glam anthem.[47][75]

Diamond Dogs was released on 24 May 1974 by RCA, with the catalogue number APLI 0576.[76][77][lower-alpha 2] The album was a commercial success, peaking at No. 1 on the UK Albums Chart and No. 5 on the US Billboard 200.[80][81] Its sales in the US were boosted by a $400,000 advertising campaign, featuring billboards in Times Square and Sunset Boulevard, magazine ads, subway poster declaring "The Year of the Diamond Dogs", as well as a television commercial, according to Pegg one of the first of its kind for a pop album.[79] In Canada, it was able to repeat its British chart-topping success, hitting No. 1 on the RPM 100 national albums chart in July 1974 and holding it for two weeks.[82] The second single, "Diamond Dogs", was released on 14 June 1974 by RCA (as APBO-0293), with a re-recorded version of Bowie's 1971 single "Holy Holy" as the B-side.[73][83] It was Bowie's least-successful single since "Starman", peaking at No. 21 on the UK Singles Chart and failing to chart in the US.[84][32]

Tour

Bowie supported the album on the Diamond Dogs Tour, which lasted from 14 June to 20 July 1974. Co-designed and constructed by Chris Langhart, the tour featured elaborate set-pieces and cost $250,000. Films that influenced the design included Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927) and Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).[85] The second portion of the tour, lasting 2 September to 1 December 1974, has been nicknamed The Soul Tour, due to the influence of the soul music Bowie had begun recording for Young Americans in August. Because of this, the shows were heavily altered, no longer featuring elaborate set-pieces, partly due to Bowie's exhaustion with the set-pieces and wanting to explore the new sound he was creating. Songs from the previous leg were dropped, while new ones (some from Young Americans) were added.[86]

Bowie played all of the album's songs except "We Are the Dead" on the tour,[57] recorded and released in two albums, David Live in 1974, and Cracked Actor in 2017.[87][88] "Rebel Rebel" featured on almost every Bowie tour afterward,[45] "Diamond Dogs" was performed for the Isolar, Outside and A Reality Tours,[89] and "Big Brother/Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family" was resurrected in 1987 for the Glass Spider Tour.[68] The tour has had a lasting legacy. Sandford states that the tour turned Bowie from a "novelty act" into a "superstar".[90] Spitz writes that the Diamond Dogs tour was highly influential on future tours with large and elaborate set pieces, including Parliament-Funkadelic's Mothership Connection tour, Elvis Presley's Vegas period, the 1990s tours of U2 and Madonna, as well as 'N Sync, the Backstreet Boys, Britney Spears and Kanye West's 2008 Glow in the Dark Tour.[91]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | C+[94] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Pitchfork | 9.0/10[31] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Select | 5/5[98] |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 3/10[99] |

The album received mixed reviews from music critics on release.[30] Disc magazine compared the album to "the greatly underrated" The Man Who Sold the World, believing it to contain some of Bowie's best-written songs and "without doubt the finest [LP] he's made so far", while Rock Magazine found it "a strong and effective album, and certainly the most impressive work Bowie's completed since Ziggy Stardust".[100] Martin Kirkup of Sounds wrote, "where Aladdin Sane seemed like a series of Instamatic snapshots taken from weird angles, Diamond Dogs has the provoking quality of a thought-out painting that draws on all the deeper colors."[10] Billboard noted the presence of a "subtler, more aesthetic Bowie" than his previous records on an album "which should reinforce his musical presence in the 70's".[79] Melody Maker called the album "really good" and offered additional praise, comparing it to Phil Spector's Wall of Sound method of production and noting the similar level of excitement and praise Bowie's albums were beginning to receive as the Beatles did in the 60s.[79] Robert Christgau was more critical in Creem, suggesting that Bowie performs a pale imitation of Bryan Ferry's "theatrical vocalism". He also dismissed the lyrical content as "escapist pessimism concocted from a pleasure dome: eat, snort and bugger little girls, for tomorrow we shall be peoploids – but tonight how about $6.98 for this piece of plastic? Say nay."[101] Ken Emerson of Rolling Stone gave the album an extremely negative review, calling it "Bowie's worst album in six years". He criticised Bowie's choice of direction, the absence of Ronson, describing Bowie's guitar playing "cheesy", further stating "the music exerts so little appeal that it’s hard to care what it's about."[102]

Retrospective appraisals have also been mixed. Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic said that, because Bowie did not completely retire the character of Ziggy Stardust, Diamond Dogs suffers from being unsure of how to progress forward. Although he praised "Rebel Rebel", he further criticised the exclusion of Ronson and ultimately concludes "it is the first record since Space Oddity where Bowie's reach exceeds his grasp."[49] Similarly, Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune gave the album a mixed review, calling it "an overproduced concept album inspired by Orwell's 1984."[93] Eduardo Rivadavia of Ultimate Classic Rock was also mixed, questioning the presence of Ziggy, whom Bowie supposedly retired the year prior. Despite the album's commercial success, Rivadavia concludes: "with decades of hindsight, Diamond Dogs now seems more like the gateway from the Ziggy Stardust era to his Thin White Duke blue-eyed soul period, and beyond."[103] On the other hand, Barry Walters of Pitchfork gave the album a positive review, describing the album as "a bummer, a bad trip, 'No Fun' – a sustained work of decadence and dread that transforms corrosion into celebration." He also believes that it foreshadowed Bowie's Thin White Duke persona.[31]

Influence and legacy

In subsequent decades, Bowie biographers have described Diamond Dogs as one of Bowie's greatest works.[24] Cann writes: "Diamond Dogs is arguably [Bowie's] most significant album, a pivotal work and the most 'solo' album he has ever made."[104] Although Spitz calls it "no fun", he states that it was Bowie's "best-sounding, most complex record to date, and it still pulls you into its romantic and doomed world three and a half decades on."[23] Buckley states that the album proved that Bowie could still produce work of "real quality" without Scott or the Spiders.[105] Doggett writes that it anticipated the "sonic audacity" of Low and "Heroes", while it simultaneously "capsized the vessel of classic rock".[106] Pegg writes that with tracks like "We Are the Dead", "Big Brother" and the "Sweet Thing" suite, the album contains "some of the most sublime and remarkable sounds in the annals of rock music."[24]

Diamond Dogs' raw guitar style and visions of urban chaos, scavenging children and nihilistic lovers ("We'll buy some drugs and watch a band / Then jump in a river holding hands") have been credited with anticipating the punk revolution that would take place in the following years.[19] According to Rolling Stone writer Mark Kemp, the album's "resigned nihilism inspired interesting gloom and doom from later goth and industrial acts such as Bauhaus and Nine Inch Nails."[107] Considering Bowie's direction afterwards through the punk and disco eras, Stylus Magazine's Derek Miller says, "Diamond Dogs should be remembered not only as one of glam’s last great full-lengths but more importantly as a gap-record that somehow manages to cohesively storyboard Bowie’s crude conceptual surrealism while also expanding his sound."[108]

Diamond Dogs has appeared on several professional listings of the best albums.[109] It ranked number 995 in the second edition of Colin Larkin's book All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000) and number 447 in NME's The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[110][111] Based on such rankings, the aggregate website Acclaimed Music lists Diamond Dogs as the 276th most acclaimed album from the 1970s and the 27th most acclaimed from 1974.[109]

Reissues

Diamond Dogs was first released on CD by RCA in 1985 with censored cover art. The German (for the European market) and Japanese (for the US market) masters were sourced from different tapes and are not identical for each region. Dr. Toby Mountain at Northeastern Digital, Southborough, Massachusetts,[112] remastered Diamond Dogs from the original master tapes for Rykodisc in 1990 with two bonus tracks and the original, uncensored, artwork. "Future Legend" stops at 1:01 and "Diamond Dogs" runs 6:04 in this version. The album was remastered by Peter Mew at Abbey Road Studios, and released without bonus material.

The third in a series of 30th Anniversary 2CD Editions, this release included a remastered version of Diamond Dogs on the first disc. The second disc contains eight tracks, five of which had been previously released on the Sound + Vision box set in 1989 or as bonus tracks on the 1990–92 Rykodisc/EMI reissues. In 2016, the album was remastered for the Who Can I Be Now? (1974–1976) box set.[113] It was released in CD, vinyl, and digital formats, both as part of this compilation and separately.[114]

Track listing

All tracks written by David Bowie, except where noted.[77]

- Side one

- "Future Legend" – 0:58

- "Diamond Dogs" – 5:56

- "Sweet Thing" – 3:37

- "Candidate" – 2:39

- "Sweet Thing (Reprise)" – 2:31

- "Rebel Rebel" – 4:30

- Side two

- "Rock 'n' Roll with Me" (Bowie/Warren Peace) – 3:57

- "We Are the Dead" – 4:58

- "1984" – 3:27

- "Big Brother" – 3:21

- "Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family" – 1:58

- 1990 Rykodisc/EMI bonus tracks

- "Dodo" (Recorded 1973) – 2:53

- "Candidate" (Demo version, very different musically and lyrically, recorded 1974) – 5:09

- 2004 EMI/Virgin bonus tracks

- "1984/Dodo" (Recorded 1973 for proposed "1984" musical) – 5:29

- "Rebel Rebel" (From "Rebel Rebel" US single A-Side, 1974) – 3:00

- "Dodo" (Also known as "You Didn't Hear It From Me", written for proposed "1984" musical, recorded 1973) – 2:53

- "Growin' Up" (Bruce Springsteen) (Recorded 1973) – 3:25

- "Candidate" (Demo version, very different musically and lyrically, recorded 1974 for proposed "1984" musical) – 5:09

- "Diamond Dogs" (K-tel The Best of Bowie edit, 1980) – 4:41

- "Candidate" (Intimacy mix, 2001) – 2:58

- "Rebel Rebel" (2003 version, from Charlie's Angels: Full Throttle soundtrack) – 3:09

Personnel

Adapted from the Diamond Dogs liner notes and biographer Nicholas Pegg.[2][77]

- David Bowie – lead and background vocals, guitars, saxophones, Moog synthesiser, Mellotron

- Mike Garson – keyboards

- Herbie Flowers – bass guitar

- Tony Newman – drums

- Aynsley Dunbar – drums

- Alan Parker – guitar on "1984"

- Production

- David Bowie – producer; mixing

- Tony Visconti – strings; mixing

- Keith Harwood – engineer; mixing

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

|

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| France (SNEP)[128] | Gold | 159,400[129] |

| Sweden (GLF)[130] | Gold | 25,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[131] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[132] | Gold | 500,000^ |

|

*sales figures based on certification alone | ||

Covers and references in popular culture

- The Serbian and former Yugoslav band Kozmetika was originally named Dijamantski Psi, which means Diamond Dogs in Serbian.[133]

- An organization in the video game Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain was named after the album. Director Hideo Kojima originally wanted to open the game with the eponymous song, but his team voted against the idea,[134] with Kojima eventually choosing a cover of "The Man Who Sold the World".

- The songwriter John Vanderslice covered the album in its entirety, releasing his version in 2013 as Vanderslice Plays Diamond Dogs.[135]

- In The Venture Bros., the Diamond Dogs are a pack of robotic dog-monsters created by the Guild of Calamitous Intent. Furthermore, the Sovereign (the leader of the Guild of Calamitous Intent) is said to be a shapeshifter in the same form of the half-human, half-dog creatures on the cover.

- In Con Air (1997), the character played by Ving Rhames holds the moniker of "Diamond Dog". He was the general in a black supremacist military group known as the Black Guerillas and was found guilty of blowing up a meeting of National Rifle Association members, claiming "they represented the basest negativity of the white race." During his incarceration, he wrote a book titled "Reflections in a Diamond Eye", which was reviewed by the New York Times as "a wake-up call for the black community."

- English gothic rock band Skeletal Family is named after the song "Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family".

Notes

- These included "I Am a Laser" and "People from Bad Homes" (early versions of "Scream Like a Baby" and "Fashion", respectively, from 1980's Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)) and a cover of the Beach Boys' "God Only Knows" (covered by Bowie for 1984's Tonight).[6][9]

- The release date is disputed. O'Leary and Sandford write it as 24 April,[73][30] while Cann and Pegg write it as 31 May.[78][79]

References

- Buckley 2005, p. 177.

- Pegg 2016, p. 642.

- Buckley 2005, pp. 176–177.

- Buckley 2005, pp. 177–178.

- Pegg 2016, p. 643.

- Buckley 2005, p. 178.

- Pegg 2016, p. 317.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 203.

- Cann 2010, p. 315.

- Buckley 2005, p. 179.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 402.

- Pegg 2016, p. 644.

- Buckley 1999, pp. 208–17.

- Buckley 2005, pp. 184–185.

- Pegg 2016, p. 646.

- Carr & Murray 1981, p. 14.

- Cann 2010, p. 283.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 406.

- Carr & Murray 1981, p. 64.

- Pegg 2016, p. 360.

- Cann 2010, p. 318.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 417.

- Spitz 2009, p. 232.

- Pegg 2016, p. 651.

- Buckley 2005, p. 189.

- Stratton 2008, p. 207.

- Waldrep, Shelton (2015). "Introduction: The Pastiche of Gender". Future Nostalgia: Performing David Bowie. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 1623569931.

- Crockford, C.M. (12 January 2015). "David Bowie – Diamond Dogs". Punknews.org. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- Sweeting, Adam (24 June 2004). "CD: David Bowie, Diamond Dogs – 30th Anniversary Edition". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Sandford 1997, p. 124.

- Walters, Barry (22 January 2016). "David Bowie: Diamond Dogs". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Pegg 2016, p. 130.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 423.

- Doggett 2012, p. 244.

- Pegg 2016, p. 129.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 425.

- Doggett 2012, p. 245.

- Raggett, Ned. ""Diamond Dogs" – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Spitz 2009, p. 231.

- Pegg 2016, p. 485.

- Buckley 2005, p. 186.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 431.

- Doggett 2012, p. 236.

- Kris Needs (1983). Bowie: A Celebration: p.29

- Pegg 2016, p. 391.

- Thompson, Dave. ""Rebel Rebel" – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Pegg 2016, p. 389.

- Buckley 2005, p. 188.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Diamond Dogs – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- Doggett 2012, p. 238.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 415.

- Pegg 2016, p. 402.

- Buckley 2005, p. 187.

- Perone 2007, p. 44.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 416.

- Doggett 2012, p. 243.

- Pegg 2016, p. 534.

- Buckley 2005, pp. 185–186.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 413.

- Pegg 2016, p. 348.

- Pegg 2016, p. 349.

- Guarisco, David A. ""1984" – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Doggett 2012, p. 230.

- Pegg 2016, p. 66.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 409.

- Doggett 2012, p. 241.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 412.

- Pegg 2016, p. 103.

- Cann 2010, p. 325.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 649–650.

- Cann 2010, pp. 323–325.

- Thompson 2015, p. 69.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 562.

- Pegg 2016, p. 390.

- Carr & Murray 1981, p. 60.

- "Diamond Dogs album is forty today". David Bowie Official Website. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Diamond Dogs (liner notes). David Bowie. RCA Records. 1974. APLI 0576.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Cann 2010, p. 322.

- Pegg 2016, p. 650.

- "David Bowie > Artists > Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- "Diamond Dogs Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- RPM Top Albums Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at Collections Canada Archived 2 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- Pegg 2016, p. 201.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 424.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 966–967.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 976–979.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "David Live – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Randle, Chris (29 June 2017). "David Bowie: Cracked Actor (Live Los Angeles '74) Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Pegg 2016, p. 131.

- Sandford 1997, p. 126.

- Spitz 2009, p. 237.

- Raihala, Ross. "David Bowie: Diamond Dogs". Blender. Archived from the original on 22 November 2005. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Kot, Greg (10 June 1990). "Bowie's Many Faces Are Profiled On Compact Disc". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Christgau, Robert (1981). "B". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved 10 July 2020 – via robertchristgau.com.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). "David Bowie". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-85712-595-8.

- "David Bowie: Diamond Dogs". Q (158): 140–41. November 1999.

- Sheffield, Rob (2004). "David Bowie". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 97–99. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Griffiths, Nick (November 1990). "Diamond Jubilation". Select (5): 124.

- Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig, eds. (1995). "David Bowie". Spin Alternative Record Guide. Vintage Books. p. 4. ISBN 0679755748.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 650–651.

- Christgau, Robert (September 1974). "The Christgau Consumer Guide". Creem. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- Emerson, Ken (1 August 1974). "Diamond Dogs". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Rivadavia, Eduardo (25 April 2015). "When David Bowie Offered the Dark, Complex 'Diamond Dogs'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Cann 2010, p. 324.

- Buckley 2005, p. 180.

- Doggett 2012, p. 248.

- Kemp, Mark (8 July 2004). "David Bowie: Diamond Dogs: 30th Anniversary Edition". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- Miller, Derek (12 June 2007). "David Bowie – Diamond Dogs – On Second Thought". Stylus Magazine. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Anon. (n.d.). "David Bowie – Diamond Dogs". Acclaimed Music. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Rocklist". Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- Barker, Emily (21 October 2013). "NME's The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time: 500–401". NME. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- "Northeastern Digital home page". Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- Who Can I Be Now? (1974–1976) details Archived 11 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine at davidbowie.com

- Bowie 'Who Can I Be Now' vinyl available separately and competitively priced Archived 12 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine at superdeluxeedition.com

- Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- "Top Albums/CDs – Volume 21, No. 24". RPM. 3 August 1974. Archived from the original (PHP) on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- "InfoDisc : Tous les Albums classés par Artiste > Choisir Un Artiste Dans la Liste". infodisc.fr. Archived from the original (PHP) on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2014. Note: user must select 'David BOWIE' from drop-down.

- "norwegiancharts.com David Bowie – Diamond Dogs" (ASP). Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- "Swedish Charts 1972–1975/Kvällstoppen – Listresultaten vecka för vecka > Juni 1974 > 11 Juni" (PDF). hitsallertijden.nl (in Swedish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2014.Note: Kvällstoppen combined sales for albums and singles in the one chart; Diamond Dogs peaked at the number-four on the list in the 1st week of June 1974.

- "Album Search: David Bowie – Diamond Dogs" (ASP) (in German). Media Control. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Australiancharts.com – David Bowie – Diamond Dogs". Hung Medien. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- "Italiancharts.com – David Bowie – Diamond Dogs". Hung Medien. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- "Portuguesecharts.com – David Bowie – Diamond Dogs". Hung Medien. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "RPM Top 100 Albums of 1974". RPM. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "Les Albums (CD) de 1974 par InfoDisc" (in French). infodisc.fr. Archived from the original (PHP) on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "The Official UK Charts Company : ALBUM CHART HISTORY". Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- "French album certifications – David Bowie – Diamond Dogs" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique.

- "Les Meilleures Ventes de CD / Albums "Tout Temps"". Info Disc. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- "From the Music Captiols of the World – Stockholm". Billboard. Vol. 42 no. 35. 22 June 1974. p. 50. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- "British album certifications – David Bowie – Diamond Dogs". British Phonographic Industry. Select albums in the Format field. Select Gold in the Certification field. Type Diamond Dogs in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- "American album certifications – David Bowie – Diamond Dogs". Recording Industry Association of America. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Album, then click SEARCH.

- Janjatović, Petar (2007), EX YU ROCK enciklopedija 1960–2006, p. 120, ISBN 978-86-905317-1-4

- "スネークの復讐は,プレイヤー自身の復讐。「METAL GEAR SOLID V: GROUND ZEROES」小島秀夫監督への単独インタビューを掲載". Archived from the original on 12 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- Vanderslice, John. "Vanderslice Plays Diamond Dogs". BandCamp. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

Sources

- Buckley, David (1999). Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-1-85227-784-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-75351-002-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cann, Kevin (2010). Any Day Now – David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974. Croyden, Surrey: Adelita. ISBN 978-0-95520-177-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record. London: Eel Pie Publishing. ISBN 978-0-38077-966-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Leary, Chris (2015). Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie from '64 to '76. Winchester: Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-78099-244-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated Edition). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perone, James E. (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27599-245-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sandford, Christopher (1997) [1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. London: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80854-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York, NY: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stratton, Jon (2008). Jewish Identity in Western Pop Culture: The Holocaust and Trauma Through Modernity. Springer. ISBN 0230612741.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Dave (2015). Goldmine Record Album Price Guide (10th ed.). Iola, Wisconsin, US: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-1-44024-891-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Diamond Dogs at Discogs.com

- Teenage Wildlife fan page with song lyrics and Rykodisc cover