Tanager

The tanagers (singular /ˈtænədʒər/) comprise the bird family Thraupidae, in the order Passeriformes. The family has an American distribution. The Thraupidae are the second-largest family of birds and represent about 4% of all avian species and 12% of the Neotropical birds.[1]

| Tanagers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Green-headed tanager, Tangara seledon | |

| Saffron finch (Sicalis flaveola) male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Superfamily: | Passeroidea |

| Family: | Thraupidae Cabanis, 1847 |

| Genera | |

|

Many: see text | |

Traditionally, about 240 species of tanagers have been described, but the taxonomic treatment of this family's members is currently in a state of flux. As more of these birds are studied using modern molecular techniques, some genera are expected to be relocated elsewhere. Already, species in the genera Euphonia and Chlorophonia, which were once considered part of the tanager family, are now treated as members of the Fringillidae, in their own subfamily (Euphoniinae). Likewise, the genera Piranga (which includes the scarlet tanager, summer tanager, and western tanager), Chlorothraupis, and Habia appear to be members of the cardinal family,[2] and have been reassigned to that family by the American Ornithological Society.[3]

Description

Tanagers are small to medium-sized birds. The shortest-bodied species, the white-eared conebill, is 9 cm (4 in) long and weighs 6 g (0.2 oz), barely smaller than the short-billed honeycreeper. The longest, the magpie tanager is 28 cm (11 in) and weighs 76 g (2.7 oz). The heaviest is the white-capped tanager, which weighs 114 g (4.02 oz) and measures about 24 cm (9.4 in). Both sexes are usually the same size and weight.

Tanagers are often brightly colored, but some species are black and white. Males are typically more brightly colored than females and juveniles. Most tanagers have short, rounded wings. The shape of the bill seems to be linked to the species' foraging habits.

Distribution

Tanagers are restricted to the Western Hemisphere and mainly to the tropics. About 60% of tanagers live in South America, and 30% of these species live in the Andes. Most species are endemic to a relatively small area.

Behavior

Most tanagers live in pairs or in small groups of three to five individuals. These groups may consist simply of parents and their offspring. These birds may also be seen in single-species or mixed flocks. Many tanagers are thought to have dull songs, though some are elaborate.

Diet

Tanagers are omnivorous, and their diets vary by genus. They have been seen eating fruits, seeds, nectar, flower parts, and insects. Many pick insects off branches or from holes in the wood. Other species look for insects on the undersides of leaves. Yet others wait on branches until they see a flying insect and catch it in the air. Many of these particular species inhabit the same areas, but these specializations alleviate competition.

Reproduction

The breeding season is March through June in temperate areas and in September through October in South America. Some species are territorial, while others build their nests closer together. Little information is available on tanager breeding behavior. Males show off their brightest feathers to potential mates and rival males. Some species' courtship rituals involve bowing and tail lifting.

Most tanagers build cup nests on branches in trees. Some nests are almost globular. Entrances are usually built on the side of the nest. The nests can be shallow or deep. The species of the tree in which they choose to build their nests and the nests' positions vary among genera. Most species nest in an area hidden by very dense vegetation. No information is yet known regarding the nests of some species.

The clutch size is three to five eggs. The female incubates the eggs and builds the nest, but the male may feed the female while she incubates. Both sexes feed the young. Five species have helpers assist in feeding the young. These helpers are thought to be the previous year's nestlings.

Systematics

Phylogenetic studies suggest the true tanagers form three main groups, two of which consist of several smaller, well-supported clades.[4][5] The list below is an attempt using information gleaned from the latest studies to organize them into coherent related groups, and as such may contain groupings not yet accepted by or are under review by the various ornithological taxonomy authorities.[6] The family contains 383 species divided into 95 genera.[7] See "List of tanagers" for all the species recognized by the International Ornithological Congress; it is sortable by common name, binomial, or taxonomic sequence.

Group 1

Mainly dull-colored forms

(a) Conebill and flowerpiercer group (Also contains Haplospiza, Catamenia, Acanthidops, Diglossa, Diglossopis, Phrygilus and Sicalis[8][5] traditionally in the Emberizidae)[9][lower-alpha 1] This group, despite having a rather varied bill morphology, shows marked plumage similarities. Most are largely gray, blue, or black, and numerous species have rufous underparts:

- Genus Conirostrum – typical conebills (10 species)

- Genus Oreomanes – giant conebill

- Genus Xenodacnis – tit-like dacnis

- Genus Catamenia (three species)

- Genus Diglossa – typical flowerpiercers (18 species)

- Genus Haplospiza (two species), paraphyletic with two species of sierra-finch Phrygilus[5]

- Genus Acanthidops – peg-billed finch

- Genus Phrygilus – sierra finches (8 species)[9][5][lower-alpha 2]

- Genus Rhopospina – mourning sierra finch

- Genus Sicalis – yellow finches (12 species), paraphyletic with Phrygilus[5]

(b) True seedeaters: Traditionally placed in the Emberizidae, these genera share a particular foot-scute pattern which suggests they may form a monophyletic group:[10]

- Genus Sporophila – typical seedeaters (over 40 species)

- Genus Charitospiza – coal-crested finch

(c) "Yellow-rumped" clade:[8]

- Genus Heterospingus (two species)

- Genus Chrysothlypis (two species)

- Genus Hemithraupis (three species)

(d) "Crested" clade (also contains Coryphospingus and Volatinia traditionally placed in the Emberizidae):

- Genus Ramphocelus – silver-billed tanagers (nine species)

- Genus Lanio – shrike-tanagers (four species)

- Genus Eucometis – gray-headed tanager

- Genus Tachyphonus (5 species)

- Genus Loriotus (three species)

- Genus Trichothraupis – black-goggled tanager

- Genus Stephanophorus – diademed tanager

- Genus Coryphospingus (two species)

- Genus Volatinia – blue-black grassquit

(e) "Blue finch" clade, relationships within the Thraupidae are uncertain, but may be related to Poospiza clade:[lower-alpha 3]

- Genus Porphyrospiza - (three species)[5]

.jpg)

(f) The Poospiza clade - a diverse but close-knit group containing both warbler- and finch-like forms:

- Genus Poospiza – warbling-finches (9 species)[5][lower-alpha 4]

- Genus Cnemoscopus – gray-hooded bush tanager

- Genus Castanozoster – bay-chested warbling finch

- Genus Poospizopsis – (2 species)

- Genus Kleinothraupis – hemispinguses (5 species)

- Genus Sphenopsis – hemispinguses (4 species)

- Genus Microspingus – (8 species)

- Genus Pseudospingus – hemispinguses (two species)

- Genus Thlypopsis (7 species)

- Genus Pyrrhocoma – chestnut-headed tanager

- Genus Cypsnagra – white-rumped tanager

- Genus Nephelornis – pardusco

(g) Grass and pampa-finches, relationships within Thraupidae are uncertain, but together form a well-supported clade:[5]

- Genus Emberizoides (three species)

- Genus Embernagra (two species)

(h) A miscellaneous and likely polyphyletic group of unplaced "tanager-finches" (which may or may not include the species called tanager-finch) whose members when studied will no doubt be relocated to other clades:

- Genus Melanodera (two species)

- Genus Rowettia – Gough Island finch

- Genus Nesospiza (three species)

- Genus Gubernatrix – yellow cardinal

- Genus Idiopsar – short-tailed finch

- Genus Piezorina – cinereous finch

- Genus Xenospingus – slender-billed finch

- Genus Incaspiza – Inca finches (five species)

- Genus Coryphaspiza – black-masked finch

- Genus Rhodospingus – crimson-breasted finch

- Genus Donacospiza – long-tailed reed finch (may be related to Poospiza[11])

(i) Basal forms in group 1:

- Genus Conothraupis (two species)

- Genus Orchesticus – brown tanager

- Genus Creurgops (two species)

Group 2

"Typical" colorful tanagers

(a) Tropical canopy tanagers:

- Genus Thraupis - T. abbas & T. episcopus at least[5][lower-alpha 5]

- Genus Pipraeidea (fawn-breasted tanager)

- Genus Tangara (about 50 species)

- Genus Poecilostreptus (2 species)

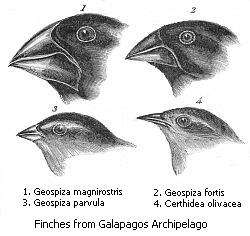

(b) "Tholospiza" - Darwin's finches, grassquits, atypical honeycreepers, and some seedeaters:[12] The finch-like forms in this clade were formerly classified in the Emberizidae:

- Genus Geospiza – ground finches (six species)

- Genus Camarhynchus – tree finches (five species)

- Genus Platyspiza - vegetarian finch

- Genus Certhidea – warbler-finches (two species)

- Genus Pinaroloxias – Cocos finch

- Genus Melopyrrha – (3 species)

- Genus Coereba – bananaquit - formerly placed in its own family Coerebidae[12][lower-alpha 6]

- Genus Tiaris – yellow-faced grassquit

- Genus Phonipara – Cuban grassquit

- Genus Melanospiza – (two species)

- Genus Asemospiza – (two species)

- Genus Loxipasser – yellow-shouldered grassquit

- Genus Euneornis – orangequit

- Genus Loxigilla – (2 species)

(c) Mountain tanagers:

- Genus Cyanicterus – blue-backed tanager

- Genus Bangsia – (six species)

- Genus Buthraupis – (two species)

- Genus Cnemathraupis – (two species)

- Genus Chlorornis – grass-green tanager

- Genus Wetmorethraupis – orange-throated tanager

- Genus Anisognathus – (five species)

- Genus Dubusia – (two species)

- Genus Pseudosaltator - rufous-bellied mountain tanager[6][lower-alpha 7]

(d) Typical tanagers:

- Genus Thraupis - (nine species)

- Genus Pipraeidea (two species)

- Genus Iridosornis (five species)

(e) Typical multicolored tanagers (includes Paroaria, traditionally placed in either the Emberizidae or Cardinalidae):

- Genus Diuca (two species)

- Genus Lophospingus (two species)

- Genus Neothraupis – shrike-like tanager

- Genus Cissopis – magpie tanager

- Genus Paroaria (five or six species)

- Genus Schistochlamys (two species)

(f) Green and golden-collared honeycreepers:[8]

- Genus Chlorophanes – green honeycreeper

- Genus Iridophanes – golden-collared honeycreeper

(g) Typical honeycreepers and relatives:[8][5][lower-alpha 8]

- Genus Tersina – swallow tanager

- Genus Cyanerpes, the typical honeycreepers (four species)

- Genus Dacnis, the dacnises (nine species)

(h) Basal lineages within group 2:

_male.jpg)

- Genus Chlorochrysa (three species)

- Genus Parkerthraustes – yellow-shouldered grosbeak (traditionally in the Cardinalidae, but biochemical evidence suggests it is a tanager[5])

- Genus Nemosia – (two species)

- Genus Compsothraupis – scarlet-throated tanager

- Genus Sericossypha – white-capped tanager

Thraupidae incertae sedis

- Genus Calochaetes – vermilion tanager

- Genus Catamblyrhynchus – plushcap

- Genus Urothraupis – black-backed bush tanager

- Genus Incaspiza - Inca finches (five species)

- Genus Saltator (14 species; traditionally placed in the Cardinalidae, but biochemical evidence suggests they may be tanagers or a sister group[5])

- Genus Saltatricula – (two species)

Recently split from Thraupidae

Related to Arremonops and other American sparrows in the Passerellidae:

- Genus Chlorospingus – bush-tanagers (around 10 species)

- Genus Oreothraupis – tanager finch

Related to the cardinals in the Cardinalidae:[6]

- Genus Piranga – northern tanagers (9 species)

- Genus Habia – ant-tanagers or habias (five species)

- Genus Chlorothraupis (three species)

- Genus Amaurospiza (four species; apparently very close to Cyanocompsa)

Fringillidae, subfamily Euphoniinae:

- Genus Euphonia (over 25 species)

- Genus Chlorophonia (five species)

Phaenicophilidae, Hispaniolan tanagers

- Genus Microligea, green-tailed warbler

- Genus Xenoligea, white-winged warbler

- Genus Phaenicophilus (two species)

Mitrospingidae, Mitrospingid tanagers

- Genus Mitrospingus, (two species)

- Genus Orthogonys, olive-green tanager

- Genus Lamprospiza, red-billed pied tanager

Nesospingidae

- Genus Nesospingus – Puerto Rican tanager

- Genus Spindalis – spindalises (four species)

- Genus Calyptophilus – chat-tanagers (two species)

- Genus Rhodinocichla – rosy thrush-tanager

Notes

- If the presence of a free lacrimal bone as found in Haplospiza, Acanthidops, and two of the three Catamenias has any phylogenetic significance, then this clade may also include several other "tanager-finches" that share this feature.

- Probably polyphyletic

- See Group 1f.

- This genus is very likely polyphyletic within its clade.

- Some members of this genus paraphyletic with respect to certain Tangara

- Exact affinities uncertain but probably sister species to Tiaris olivacea in the "Tholospiza"

- Apparently close to mountain-tanagers Dubusia and Delothraupis

- May be closer to group 1

References

- Burns, K.J.; Shultz, A.J.; Title, P.O.; Mason, N.A.; Barker, F.K.; Klicka, J.; Lanyon, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. (2014). "Phylogenetics and diversification of tanagers (Passeriformes: Thraupidae), the largest radiation of Neotropical songbirds". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 75: 41–77. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.02.006. PMID 24583021.

- Yuri, T.; Mindell, D. P. (May 2002). "Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Fringillidae, "New World nine-primaried oscines" (Aves: Passeriformes)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 23 (2): 229–243. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00012-X. PMID 12069553.

- "Family: Cardinalidae". American Ornithological Society. Retrieved Feb 1, 2019.

- Fjeldså, J.; Rahbek, C. (2006). "Diversification of tanagers, a species rich bird group, largely follows lowlands to montane regions of South America". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 46 (1): 72–81. doi:10.1093/icb/icj009. Archived from the original on 2012-05-25.

- Klicka, J.; Burns, K.; Spellman, G. M. (December 2007). "Defining a monophyletic Cardinalini: A molecular perspective". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 45 (3): 1014–1032. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.07.006. PMID 17920298.

- "A Classification of the Bird Species of South America". LSU.edu. South American Classification Committee, American Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "New World warblers, mitrospingid tanagers". IOC World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- Burns, K. J.; Hackett, S. J.; Klein, N. K. (2003). "Phylogenetic relationships of Neotropical honeycreepers and the evolution of feeding morphology". J. Avian Biol. 34 (34): 360–370. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2003.03171.x.

- Webster, J. D.; Webster, J. R. (1999). "Skeletons and the genera of sparrows (Emberizinae)". Auk. 116 (116): 1054–1074. doi:10.2307/4089685. JSTOR 4089685.

- Clark (1986)

- Ridgely, R. S.; Tudor, G. (1989). The Birds of South America. 1. Austin: Univ. Texas Press. p. 472.

- Burns, K. J.; Hackett, S. J.; Klein, N. K. (2003). "Phylogenetic relationships and morphological diversity in Darwin's finches and their relatives". Evolution. 56 (56): 1240–1252. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2002)056[1240:pramdi]2.0.co;2.

- Bent, Arthur Cleveland Bent (1965). Life Histories of Blackbirds, Orioles, Tanagers, and Allies. New York: Dover Publications.

- Clark, G. A., Jr. (1986). "Systematic interpretations of foot-scute patterns of Neotropical finches" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. The University of New Mexico. 98 (4): 594–597.

- Greeney, H. (2005). "Nest and eggs of the Yellow-whiskered Bush Tanager in Eastern Ecuador". Ornitologia Neotropical (16): 437–438.

- Hellmayr, C. E. (1935). "Catalogue of birds of the Americas and the adjacent islands in Field Museum of Natural History". Fieldiana Zoology. 13 (8–"Coerebidae").

- Hellmayr, C. E. (1936). "Catalogue of birds of the Americas and the adjacent islands in Field Museum of Natural History". Fieldiana Zoology. 13 (9–"Tersinidae – Thraupidae").

- Hellmayr, C. E. (1938). "Catalogue of birds of the Americas and the adjacent islands in Field Museum of Natural History". Fieldiana Zoology. 13 (11–"Ploceidae – Catamblyrhynchidae – Fringillidae").

- "InfoNatura Species Index: family Thraupidae". natureserve.org. June 2005. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- Isler, Morton L.; Isler, Phyllis R. (1987). The Tanagers: Natural History, Distribution, and Identification. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 9780874745535.

- Latta, S.; et al. (2006). Aves de la República Dominicana y Haití [Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti] (in French). Princeton University Press.

- Lougheed, S. C.; Freeland, J. R.; Handford, P.; Boag, I. T. (2000). "A molecular phylogeny of warbling-finches (Poospiza): paraphyly in a Neotropical emberizid genus". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 17 (3): 367–378. doi:10.1006/mpev.2000.0843. PMID 11133191.

- Naoki, Kazuya (2003). Evolution of Ecological Diversity in the Neotropical Tanagers of the Genus Tangara (Aves: Thraupidae) (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). Louisiana State University. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- Roberson, Don (July 6–11, 2000). "Tanagers (Thraupidae)". CREAGUS at montereybay.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2006.

- Sato, A.; O'Huigin, C.; Figueroa, F.; Grant, P. R.; Grant, B. R.; Tichy, H.; Klein, J. (1999). "Phylogeny of Darwin's finches as revealed by mtDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 (9): 5101–5106. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.9.5101. PMC 21823. PMID 10220425.

Further reading

- Barker, F.K.; Burns, K.J.; Klicka, J.; Lanyon, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. (2013). "Going to extremes: contrasting rates of diversification in a recent radiation of New World passerine birds". Systematic Biology. 62 (2): 298–320. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys094. PMID 23229025.

- Barker, F.K.; Burns, K.J.; Klicka, J.; Lanyon, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. (2015). "New insights into New World biogeography: An integrated view from the phylogeny of blackbirds, cardinals, sparrows, tanagers, warblers, and allies". Auk. 132 (2): 333–346. doi:10.1642/AUK-14-110.1.

- Burns, K.J.; Unitt, P.; Mason, N.A. (2016). "A genus-level classification of the family Thraupidae (Class Aves: Order Passeriformes)". Zootaxa. 4088 (3): 329–354. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4088.3.2. PMID 27394344.

- Remsen, J.V. Jr (2016). "Proposal 730: Revise generic limits in the Thraupidae". South American Classification Committee, American Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thraupidae. |

- Jungle-walk.com tanager pictures

- Tanager videos, photos and sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- Thraupidae at Curlie