Strathfield, New South Wales

Strathfield is a suburb in the Inner West of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located 12 kilometres west of the Sydney central business and is the administrative centre of the Municipality of Strathfield. A small section of the suburb north of the railway line lies within the City of Canada Bay, while the area east of The Boulevard lies within the Municipality of Burwood. North Strathfield and Strathfield South are separate suburbs to the north and south, respectively.

| Strathfield Sydney, New South Wales | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contemporary apartments in the commercial area | |||||||||||||||

| Population | 25,813 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 3,928.9/km2 (10,176/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | c.1868 | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 2135 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 6.57 km2 (2.5 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 11.5 km (7 mi) west of Sydney CBD | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | |||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Strathfield | ||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Reid, Watson | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

History

The Strathfield district was originally occupied by the Wangal clan. European colonisation commenced in 1793 with the issue of land grants in the area of Liberty Plains. In 1808, a grant was made to James Wilshire, which forms the largest part of the current suburb of Strathfield. In 1867, this grant was subdivided and sold as the 'Redmire Estate', which promoted the residential development of the district under the suburb name of 'Redmire'. By 1885, sufficient numbers of people resided in the district to enable incorporation of its own local government. The suburb of Redmire was renamed Strathfield c.1886. The suburb was named after a house called 'Strathfield House', which was originally called Stratfield Saye.[2] In 1885, Strathfield Council was incorporated.

Birth of Strathfield

James Wilshire was granted 1 square kilometre (0.39 sq mi) of land by Governor Macquarie in 1808 [regranted 1810] following representations from Lord Nelson, a relation by marriage of Wilshire. Ownership was transferred in 1824 to ex-convict Samuel Terry. The land became known as the Redmire Estate, which Michael Jones says could either be named after his home town in Yorkshire or could be named after the "red clay of the Strathfield area".[3] Subdivision of the land commenced in 1867. An early buyer was one-time Mayor of Sydney, Walter Renny who built in 1868 a house they called Stratfieldsaye, possibly after the Duke of Wellington's mansion near Reading, Berkshire. It may have also been named after the transport ship of the same name that transported many immigrants – including Sir Henry Parkes – to Australia, though the transport ship was probably also named after the Duke's mansion as it was built soon after his death and was likely named in his honour. A plaque marking the location of Stratfield Saye can be found in the footpath of Strathfield Avenue, marking the approximate location of the original house [though some of the wording on the plaque is incorrect]. According to local historian Cathy Jones, "ownership of [Stratfieldsaye] was transferred several times including to Davidson Nichol, who shortened the name to 'Strathfield House', then 'Strathfield'."[4][5]

Strathfield was proclaimed on 2 June 1885 by the Governor of NSW, Sir Augustus Loftus, after residents of the Redmyre area petitioned the New South Wales State government. Residents in parts of Homebush and Druitt Town [now Strathfield South] formed their own unsuccessful counter-petition. It is likely that the region was named Strathfield to neutralise the rivalry between Homebush and Redmire.

Strathfield Council

Strathfield Council was incorporated in 1885 and included the suburbs of Redmire, Homebush and Druitt Town. The adjoining area of Flemington was unincorporated and was annexed to Strathfield Council in 1892, which increased the size of the Council area by about 50%. The Council formed three wards – Flemington,Homebush and Strathfield – and Aldermen was elected to represent their ward at Council. Wards were abolished in 1916.[6][7] Following the introduction of the Local Government Act in 1919, Strathfield Council was one of the first to proclaim the major part of its area a residential district by proclamation in 1920.

Strathfield Murders

On 17 August 1991, seven people were killed, when Wade Frankum stabbed a fifteen-year-old girl to death, before running amok with a rifle in the Strathfield Plaza shopping mall, and then turning the weapon on himself. This is commonly known as the Strathfield Massacre. A Memorial plaque is located at Churchill Avenue, Strathfield.

Heritage listings

Strathfield has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

- 25A Barker Road: Mount St Mary Campus of the Australian Catholic University[8]

- Great Southern and Western railway: Strathfield rail underbridges[9]

- Great Southern and Western railway: Strathfield railway station[10]

- 62 The Boulevarde: Trinity Uniting Church, Strathfield[11]

Schools and churches

Independent schools

- St Patrick's College is an independent, day school for boys.

- Santa Sabina College is a Roman Catholic, Dominican, day school for girls K-12 and boys K-4. The primary school is known as Santa Maria Del Monte.

- Meriden Anglican School for Girls is an independent, Anglican, day school for girls..

- Trinity Grammar School Preparatory School campus is on The Boulevarde[12] and has classes from Pre-Kindergarten to Year 6.[13][14]

- St Martha's Primary School

State schools

- Strathfield Girls High

- Strathfield South Public School

- Strathfield South High School

- Chalmers Road Public School (state government school for students aged four to eighteen years with moderate or severe intellectual disabilities)

- Marie Bashir Public School

Tertiary institutions

- A campus of the Australian Catholic University, the former home of the Christian Brothers novitiate and Catholic Teachers' College.

- The Catholic Institute of Sydney, where priests for the Archdiocese of Sydney, and other theologians and ministers, are trained, is located on the site of the old Australia Post training centre.

Churches

- Carrington Avenue Uniting Church

- St Anne's Anglican Church

- St David's Presbyterian Church

- St Martha's Catholic Church[15]

- Sts Peter and Paul Russian Orthodox Cathedral

- Ukrainian Autocephalic Orthodox Church of the Protection of the Theotokos

- Strathfield Korean Uniting Church

- Sydney Chinese Seventh-day Adventist Church

- Trinity Uniting Church, Strathfield

- Western Sydney Chinese Christian Church

Residential landscape

Strathfield's residential landscape is extremely varied, ranging from country-style estates to high-rise apartments. Many styles of architecture have been employed over past decades, with dwellings having been constructed in Victorian, Federation, Interwar period architecture, Californian Bungalow and contemporary periods. One of the oldest surviving houses built in the 1870s is Fairholm which is now a retirement village called Strathfield Gardens.

Primarily these have been replaced by modern, multimillion-dollar mansions, although Strathfield has retained its wide avenues and most of the extensive natural vegetation. Streets such as Victoria Street, Llandillo Avenue and Kingsland Road predominantly feature older mansions, while Agnes Street, Newton Road and Barker Road are common locations for new homes.

The "Golden Mile" in Strathfield refers to a pocket within the suburb that houses some of the most desirable and highly sought-after real estate in the area.[16] The Golden Mile is bounded by Hunter Street, Carrington Avenue, Homebush Road and The Boulevarde. Examples of prestigious addresses include homes located on Cotswold Road,[17] Strathfield Avenue,[18] Llandilo Avenue, Agnes[19] and Highgate Street.

Additionally, decreasing land sizes through subdivision has led to an increase in residential densities, reflecting the outward expansion of Sydney's inner city. A large proportion of Strathfield's population now dwells in apartments with the area immediately surrounding Strathfield railway station dominated by high rise residential towers. Smaller apartment buildings are located in other areas within the suburbs, were mostly built during the 1960s and 1970s.

In the last century a number of grand Strathfield homes become independent school campuses:

- Holyrood – Santa Sabina

- Brunyarra – Santa Maria Del Monte[20]

- Lauriston – Santa Maria Del Monte[21]

- Llandilo – Trinity Grammar School[22]

- Somerset – Trinity Grammar School[23]

- Milverton – Trinity Grammar School[22]

- Riccarton/The Briars – Meriden and partially demolished[24][25]

- Wariora – Meriden and now demolished[26]

- Lingwood/Branxton – PLC Sydney and now Meriden School[22]

- Selbourne – Meriden and now demolished[27][28]

- Telerah – Wadham Preparatory School, later purchased by Meriden and now demolished[29]

Commercial area and transport

Strathfield is known as a regional centre for education. Strathfield town centre contains Strathfield Plaza shopping centre which includes Woolworths and other stores. There are also a small strip of shops, restaurants, cafes and a Police shopfront.

Strathfield railway station is a major interchange on the Sydney Trains and NSW TrainLink networks and for buses serving the inner west.

The M4 Western Motorway begins at Strathfield and heads west to Parramatta, Blacktown and Penrith. Parramatta Road links Strathfield east to Burwood and the Sydney CBD and west to Parramatta.

Demographics

According to the 2016 census, Strathfield had a total population of 25,813 people. 34.6% of people were born in Australia. The most common other countries of birth were China 10.3%, India 10.1%, South Korea 9.8%, Nepal 5.3% and Vietnam 2.7%. The most common ancestries were Chinese 19.6%, Indian 10.0%, Korean 9.9%, English 7.4% and Australian 6.9% with 75.6% of people having both parents born overseas.

29.1% of people only spoke English at home. Other languages spoken at home included Korean 10.9%, Mandarin 10.6%, Cantonese 7.6%, Nepali 5.3% and Tamil 4.0%. The most common responses for religion were No Religion 23.3%, Catholic 23.1% and Hinduism 16.2%.[1]

Residents

The following were either born or have lived at some time in the suburb of Strathfield:

Architecture

- George Sydney Jones (1868–1927), architect of Trinity Congregational Church and the following Strathfield houses; Springfort (1894); Darenth (1895); Bickley (1894); Treghre (1899); and Luleo (1912).[30]The Strathfield Catholic Institute was built in 1891 as the Institute for Blind Women and designed by Harry Kent

- Harry Kent (1852–1938), architect, alderman for the Municipality of Strathfield and architect of the Strathfield Town Hall.

Business

- William Arnott, founder of Arnott's Biscuits.[31]

- Sir Robert Crichton-Brown (1919–2013), businessman, soldier and sailor, lived in Strathfield in the 1920s and 1930s.

- Charles Henry Hoskins (1851-1926), industrialist and businessman, lived in Strathfield during the 1890s and 1900s.[32][33]

- Edward Lloyd Jones (1844–1894), head of the department store David Jones Limited, and his son;

- Edward Lloyd Jones (1874–1934), Shorthorn cattle breeder and former chairman of David Jones Limited, and his brother;

- Charles Lloyd Jones (1878–1958), former chairman of David Jones Limited and former chairman of the Australian Broadcasting Commission.

Fashion and society

- Lady McMahon (1932–2010), spouse of the 20th Prime Minister of Australia, was born in Strathfield.

Law

- David Wilson KC (1879–1965), barrister and company director.

Medicine

- Sir Philip Sydney Jones (1836–1918), medical practitioner and University of Sydney vice-chancellor lived at Llandilo on The Boulevarde.

Politics

- Sir George Houston Reid, Prime Minister of Australia, 4th Prime Minister of Australia.

- Earl Page (1880–1961), 11th Prime Minister of Australia.

- Frank Forde, Prime Minister of Australia, 15th Prime Minister of Australia.

Religion

- Rev Professor Hubert Cunliffe-Jones (1905–1991): Congregational church minister, chair of the Congregational Union of England and Wales and a Professor at the University of Manchester was the son of the Rev Walter Cunliffe-Jones of the Strathfield-Homebush Congregational church (now Uniting Church – Korean Parish).

Science

- F. J. Duarte: author and physicist, lived in Leicester Avenue, Strathfield.

Sport

- Alan Davidson (born 1929), cricketer

- Daphne Akhurst (1903–1933), tennis player

Other people

- Katharine Gatty, suffragette

- Anu Singh, convicted of murdering her boyfriend

- Derek Percy, convicted child killer

Culture

Strathfield has made an impact on the indie rock and indie pop scene, producing bands such as Prince Vlad & the Gargoyle Impalers, Lunatic Fringe, The Mexican Spitfires and Women of Troy. It has also inspired pop songs such as The Mexican Spitfires's song "Rookwood" about Rookwood Cemetery and the legendary Blitzkrieg punk rock of Radio Birdman's classic mid-1970s "Murder City Nights". Indie pop legend Grant McLennan of The Go-Betweens also called Carrington Avenue, Strathfield home for a few years in the 1990s.

Gallery

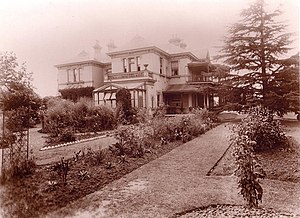

- Glen Luna, a house on Carrington Street, has been converted into apartments.

- Holyrood, a house on The Boulvarde, has become part of Santa Sabina.

St Anne's Anglican Church

St Anne's Anglican Church- Santa Sabina College

Trinity Grammar 1930

Trinity Grammar 1930 Strathfield council chambers (c. 1915)

Strathfield council chambers (c. 1915) Strathfield Council Chambers present day

Strathfield Council Chambers present day

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Strathfield (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Jones, Cathy. "Origin of the name of Strathfield". Strathfield Heritage Website. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- Jones, Michael (1985). Oasis in the West: Strathfield's first hundred years. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin Australia. ISBN 0-86861-407-6.

- Jones, Cathy (2004). Strathfield – origin of the name Archived 18 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 4 October 2004.

- Jones, Cathy [2005], A [very] short history of Strathfield, Strathfield District Historical Society Newsletter.

- Reps, John W. Fitgerald, Critique of Capital City Plans Archived 6 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Cornell University.

- Fitzgerald, John Daniel (27 July 1912). The Capital plans, the city of the future. The Sydney Morning Herald.

- "Mount St Mary Campus of the Australian Catholic University". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01965. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "Strathfield rail underbridges (flyover)". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01055. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Strathfield Railway Station group". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01252. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Trinity Uniting Church". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01671. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Trinity Gramma School". Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "Australian School Choice- St Patrick's College". Archived from the original on 5 May 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "Trinity Grammar School". Schools. Australian Boarding Schools' Association. 2007. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- D. Gleeson, Monsignor Peter Byrne and the foundations of Catholicism in Strathfield, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 35 (2014) Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 38–50.

- "Strathfield – The Golden Mile". Archived from the original on 15 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "Cotswold Road, The Golden Mile, Strathfield". Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "Stratfield Avenue – The Golden Mile". Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "Agnes Street – The Golden Mile". Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "'Brunyarra' The Boulevarde Strathfield". strathfieldhistory.org. 23 January 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- "'Lauriston' The Boulevarde". strathfieldhistory.org. 25 January 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- "Schools". strathfieldhistory.org. 2 September 2009. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- "'Somerset' The Boulevarde Stratfield". strathfieldhistory.org. 2 September 2009. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Review of Environmental Factors – Meriden Strathfield, NSW Archived 5 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Foster, A. G. (Arthur G.) (1920), Meriden, Church of England school for girls, Redmyre Road, Strathfield, N.S.W, retrieved 6 May 2019

- Foster, A. G. (Arthur G.) (1920), Exterior view of Meriden Annexe, Strathfield, retrieved 6 May 2019

- "WEDDINGS Earwaker—Woolnough". Queensland Figaro. XXXIII (51). Queensland, Australia. 24 December 1927. p. 12. Retrieved 6 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- Strathfield Heritage – All about the history and heritage of Strathfield Archived 2 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Wadham Preparatory School, Strathfield Heritage Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Archived 23 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 August 2012

- Mander-Jones, Phyllis. Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2018 – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- "Holyrood | NSW Environment, Energy and Science". www.environment.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Santa Sabina College – Holyrood". Strathfield Heritage. 3 October 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Strathfield, New South Wales. |

External links

- http://www.strathfieldheritage.org

- Han, Gil-Soo; Han, Joy J. (2010). "Koreans". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 4 October 2015. [CC-By-SA] (Koreans in Sydney)