Restored Government of Virginia

The Restored (or Reorganized) Government of Virginia was the Unionist government of Virginia during the American Civil War (1861–1865) in opposition to the government which had approved Virginia's seceding from the United States and joining the new Confederate States of America. Each government regarded the other as illegitimate; the Restored Government had de facto control of the state's northwest until, with its approval, the area became West Virginia in mid-1863. Since the Restored Government and West Virginia mutually recognized each other, the former government thereafter became in large part a government in exile. Until the end of hostilities, most of its de jure territory remained controlled by the secessionist state government, which never recognized either Unionist state government operating within its antebellum borders. Furthermore, since the Restored Government's claimed territory not under secessionist control only remained so by force of arms it was placed under Federal martial law, thus further limiting the authority of the Unionist civilian government.

| Restored Government of Virginia | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restored state government of United States of America | |||||||||||

| 1861–1865 | |||||||||||

.png) Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

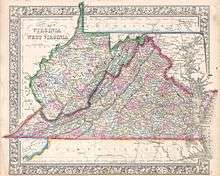

1864 map of the states of West Virginia and Virginia by Samuel Augustus Mitchell. The Restored Government of Virginia claimed to be the rightful government of these lands until the admission of the State of West Virginia into the Union in 1863, after which claiming the control of the modern state boundaries of Virginia. | |||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||

| • Type | Organized incorporated state | ||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

• 1861–1865 | Francis Harrison Pierpont | ||||||||||

| Historical era | American Civil War (1861–1865) | ||||||||||

| June 11, 1861 | |||||||||||

• Formation of a new state government | June 19 1861 | ||||||||||

| June 20, 1863 | |||||||||||

| April 9, 1865 | |||||||||||

• Provisional government formed in Richmond | May 9 1865 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Restored Government had only executive and legislative branches; it did not form a judicial branch. It met in Wheeling, in the extreme northwestern corner of the state, until that became part of West Virginia. From August 26, 1863 until June 1865, it met in Alexandria on the northeast edge of the state, which had been occupied by Union Army forces in 1861 to protect the adjacent national capital of Washington, D.C.. The Restored Government claimed Richmond as its de jure capital from its formation. It eventually moved there near the end of the war after the rebel Confederate States government and General-in-Chief Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia evacuated it as their capital in late March 1865, and the city shortly returned to Federal control.

Formation

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 376,688 | — |

| Source: 1860 (West Virginia only);[1] | ||

|

|

Union states in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

| Dual governments |

| Territories and D.C. |

When the Second Wheeling Convention met in its first session, in June 1861, it adopted "A Declaration of the People of Virginia".[2] The declaration stated that the Virginia Declaration of Rights required any substantial change in the form or nature of state government to be approved by the people. Since the Virginia secession convention had been convened by the legislature, not the people, the declaration pronounced the secession convention illegal, and that all of its acts—including the Ordinance of Secession—were ipso facto void. It also declared the pro-secession government void and called for a reorganization of the state government, taking the line that all state officials who had acceded to the Ordinance of Secession had effectively vacated their offices. The members and officers of the Restored Government had themselves not been elected by the people to the offices they had assumed, but instead convened on the basis of local petition and other irregular accreditation, some "more or less self-appointed".[3]

The convention then elected Francis Harrison Pierpont as governor, along with other executive officers, with Wheeling as the provisional state capital. 16th President Abraham Lincoln recognized the Restored Government as the legitimate government of the entire Commonwealth of Virginia.[4] The United States Congress seated the two new United States Senators chosen by its legislature, and five U.S. representatives elected from the territories that remained loyal to the Union or were occupied by the Union Army. Its Congressional delegation in the 37th United States Congress was entirely made up of Unconditional Unionists. U.S. Senators elected were Waitman T. Willey and John S. Carlile. Representatives were seated from where delegates in the Richmond Convention of 1861 had voted to remain in the Union. They were the western 10th, William G. Brown, the 11th, Jacob B. Blair, and 12th, Kellian V. Whaley, in Congressional Districts of counties that would mostly become the 35th State of West Virginia, along with the 7th, Charles H. Upton, from Alexandria and Fairfax County, and the 1st, Joseph E. Segar in the Eastern Shore and Tidewater Peninsulas. Following the loss of its governance over the population of West Virginia, Congress in the 38th United States Congress did not seat either Senators elected by the Restored General Assembly, nor Representatives elected in truncated elections in Union-occupied areas of Virginia; the entire state's delegation went vacant.[5]

By the end of 1861, large Confederate States Army forces had abandoned western Virginia after contesting the region with overwhelming Federal units, but small brigades of Confederate soldiers commanded by William Lowther Jackson and Albert G. Jenkins operated throughout the area during the war. The Restored Government attempted to exercise de facto authority, at least over the western counties, but had control of no more than half of the fifty counties that became West Virginia.[6] On August 22, 1862, the Restored Government's Adjutant General, Henry I. Samuels, reported to Gov. Pierpont that there were 22 counties in which they could raise Union volunteers, but "...in several of the Counties I have named, a draft would be an operation of extreme difficulty...."[7]

Government in Wheeling

A movement for separate statehood had grown in the trans-Allegheny region of western Virginia long before the outbreak of war mirroring similar sentiments of other western mountainous portions of other East Coast states. A key obstacle to separate admission to the Union was that a provision in the United States Constitution of 1787 forbade the creation of new states out of existing ones without the consent of the existing state's legislature. Soon after the President and the Congress recognized the Restored Government as the legitimate government of Virginia, it asserted its authority to give such consent. The legislature that met between the two sessions of the Wheeling Convention in 1861 failed to pass a statehood bill,[8] but the second session of the convention approved it. A popular referendum in October 1861 was called on the creation of the new "State of Kanawha" from the northwestern counties of the old Commonwealth of Virginia. The voters' approval led to a constitutional convention, and another popular vote in April 1862 approving the new constitution for a new state, the now renamed "West Virginia".[9] The U.S. Congress then passed a statehood bill for West Virginia, but with the added condition that slaves be emancipated in the new state, and that certain disputed counties be excluded.[10] President Lincoln, although reluctant to divide Virginia during a war aimed at re-uniting the country, eventually signed the statehood bill into law on December 31, 1862.[11] In Wheeling, the added conditions required another constitutional convention and popular referendum. Statehood was achieved on June 20, 1863 as West Virginia was admitted as the 35th state in the Union and an additional star was added to the American flag a few weeks later on Independence Day on the Fourth of July.

Restored Legislature of Virginia in Wheeling

The following table shows the legislature of the Restored Government, men who had been elected to the General Assembly in Richmond but refused to assume office there. Those counties marked with an * are still in Virginia. Legislators with a + after their names had been in the previous General Assembly.[12]

| County/Counties | Name | Office |

|---|---|---|

| *Alexandria | Miner, Gilbert S. | Delegate |

| Barbour | Myers, David M. | Delegate |

| Brooke | Crothers, H.W. | Delegate |

| *Fairfax | Hawxhurst, John | Delegate |

| Gilmer, Calhoun, Wirt | Williamson, James A. | Delegate |

| Hampshire | Trout, James H. | Delegate |

| Hampshire | Downey, Owen D. | Delegate |

| Hancock | Porter, George McC. + | Delegate |

| Hardy | Michael, John | Delegate |

| Harrison | Davis, John J. | Delegate |

| Harrison | Vance, John C. | Delegate |

| Jackson, Roane | Frost, Daniel + | Delegate |

| Kanahwa, Roane | Ruffner, Lewis | Delegate |

| Lewis | Arnold, George T. | Delegate |

| Marion | Smith, Fountain | Delegate |

| Marion | Fast, Richard | Delegate |

| Marshall | Swan, Remembrance | Delegate |

| Mason | Wetzel, Lewis | Delegate |

| Monongalia | Kramer, Leroy | Delegate |

| Monongalia | Snyder, Joseph | Delegate |

| Ohio | Logan, Thomas H. | Delegate |

| Ohio | Wilson, Andrew | Delegate |

| Pleasants, Ritchie | Williamson, James W. | Delegate |

| Preston | Zinn, William B. | Delegate |

| Preston | Hooten, Charles | Delegate |

| Randolph, Tucker | Parsons, Solomon | Delegate |

| Taylor | Davidson, Lemuel E. | Delegate |

| Tyler, Doddridge | Boreman, William I. | Delegate |

| Upshur | Farnsworth, Dan D.T. | Delegate |

| Wayne | Radcliffe, William | Delegate |

| Wetzel | West, James G. | Delegate |

| Wood | Moss, John W. | Delegate |

| *Alexandria, *Fairfax | Close, James T. | Senator |

| Calhoun, Gilmer, Lewis, Upshur, Barbour, Randolph, Tucker | Jackson, Blackwell | Senator |

| Hampshire, Hardy, Morgan | Carskadon, James | Senator |

| Hancock, Brooke, Ohio | Gist, Joseph | Senator |

| Marshall, Wetzel, Tyler, Marion | Burley, James | Senator |

| Mason, Cabell, wayne, Jackson, Wirt, Roane | Flesher, Andrew | Senator |

| Monongalia, Preston, Taylor | Cather, Thomas | Senator |

| Ritchie, Doddridge, Harrison, Pleasants, Wood | Stuart, Chapman J. | Senator |

Secessionist attitudes toward the Governments in Wheeling

Secessionists in Richmond harbored strong opinions regarding loyalty to one's own state, as evidenced by the then-recent trial and execution of John Brown who was condemned on a charge of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. In this environment, legislators who assembled in Wheeling were branded as "traitors" against the Commonwealth. However, the significant legal and constitutional irregularities surrounding the formation of the Wheeling Conventions also gave the secessionists strong legal arguments with which to challenge the legitimacy of the Wheeling Government and legality of its actions, in particular its claimed authority to partition the Commonwealth.

Partly in order to bolster its claim to be the only lawful government of Virginia, the secessionist government in Richmond adhered to constitutional formalities when purging Unionist officials. The aforementioned legislators who assembled in Wheeling were expelled by the Virginia General Assembly while officials in other branches who remained loyal to the Union were replaced through the impeachment process. The secessionist Assembly quickly set about organizing special elections to fill the resulting legislative vacancies in the affected districts. Many of these elections were held at the same time as elections to the first permanent Confederate States Congress, which unlike the U.S. Congress was slated to be elected at the end of odd numbered years.

Suspected Unionists were often disenfranchised, intimidated or otherwise prevented from participating in subsequent secessionist elections, with Unionists responding in kind to prevent those with suspected secessionist sympathies from participating in Unionist elections. For the most part however, voters simply boycotted elections to those legislatures they did not recognize. As a result, many locales in Virginia elected secessionist legislators to sit in the legislature meeting in Richmond even as unionist legislators continued to meet in Wheeling. Furthermore, as the Confederate States Constitution granted Virginia 16 seats in the Confederate States House of Representatives (compared to the 13 Virginia had in the U.S. House) the secessionist legislature quickly drew up new Congressional districts which without regard either to whether their forces controlled the territory or to the loyalties of the local residents therein. Nevertheless, by this time it was obvious even to secessionists there was no realistic hope that Confederates would be able to stage conventional elections in the far northwestern regions of the Commonwealth. To ensure every district's seat could be filled regardless of the Confederates' ability to hold an election there, Confederate and rebel state authorities were far less stringent than Unionists in terms of seating pro-secessionist legislators elected by those claiming residency in locales under Union occupation, thus even regions firmly under Union control continued to be putatively represented in Richmond at both the state and national (i.e. Confederate) by firmly secessionist legislators.

Since the secessionist government did not recognize West Virginia, these attitudes and the ensuing electoral arrangements continued essentially unchanged after West Virginia's admission to the Union with respect to the territory claimed by the new state. Thus, even as Unionists assembled for the first session of the newly-created West Virginia Legislature in Wheeling secessionists continued to represent the same locales in both the Virginia General Assembly and Confederate States Congress meeting in Richmond. In spite of relatively steady Confederate military reverses, the secessionist Commonwealth government in Richmond continued to maintain at least tenuous control over West Virginia's southernmost counties until the conclusion of the war.

Government in Alexandria

Following West Virginia's statehood in June 1863, the Restored Government of Virginia relinquished authority over the northwestern counties now forming the new 35th state, and thus lost most of its area not under Confederate military control. Pierpont then moved the Restored Government from Wheeling to Alexandria, effective August 26, 1863. Located in northeast Virginia proper, across the Potomac River from Washington, the city of Alexandria remained under Union control for most of the war since May 1861. The Restored Government claimed legitimacy over all of the Commonwealth of Virginia not now incorporated into the new State of West Virginia. Rather than recognize the Confederate state government in Richmond, Pierpont had characterized it as "large numbers of evil-minded persons [that] have banded together in military organizations with intent to overthrow the Government of the State; and for that purpose have called to their aid like-minded persons from other States, who, in pursuance of such call, have invaded this Commonwealth."[4] But outside the few jurisdictions that Pierpont's government administered under Federal military and naval arms along the Potomac River and around the Hampton Roads harbor and along the Chesapeake Bay, control of the state was mostly in rebel Richmond, for instance, in collecting taxes. Furthermore, Federal military authorities consistently enforced martial law in those regions of the state under Union military control, which was for all intents and purposes the whole of the state not under rebel control. The imposition of martial law further limited the Restored Government's actual civil authority.

The Restored Government's loss of authority had direct consequences for Pierpont's own political career. He was born in West Virginia, firmly identified as a West Virginian and had hoped to become Governor of the new state. However, there were very few suitably qualified Unionists with ties to a locale within the Commonwealth's reduced borders and none who expressed interest in replacing Pierpont to become essentially a figurehead chief executive. Therefore, Pierpont reluctantly agreed to continue to head the Restored Government in Alexandria while Arthur I. Boreman became the first Governor of West Virginia. In this role, Pierpont ensured the Restored Government would continue to assert its authority over the remainder of the Commonwealth and conduct whatever business it could. As had been (and continued to be) case with respect to dual representation in the Wheeling and Richmond assembles, several Virginia localities not claimed by West Virginia sent representatives to both the rival Alexandria and Richmond state legislatures.[13]

The Restored Government adopted a new Virginia constitution in 1864 by declaration (rather than by popular vote as delegate John Hawxhurst of Fairfax County, Virginia had advocated). It recognized the creation of West Virginia, abolished slavery, and disqualified supporters of the Confederacy from voting. The constitution was effective only in the Union-controlled areas of Virginia: several northern Virginia counties, the Norfolk / Portsmouth / Hampton areas around Hampton Roads, and the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake.[14]

On February 9, 1865 the legislature of the Restored Government voted for the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished slavery in the United States.

Government moves to Richmond

After the fall of Richmond and the end of the Civil War in May 1865, the executive officers moved the government from Alexandria to Richmond, which the Restored Government had always considered to be its official capital. The government operating under the Constitution of 1864 thereafter assumed civil authority for the entire Commonwealth of Virginia, until adoption of the Constitution of 1869. Some West Virginians expressed concern that once restored to the Union the government of Virginia might seek to challenge the validity of the authority the Restored Government possessed in consenting to West Virginia's admission to the Union. To alleviate these concerns, the Congress set as a condition for Virginia's readmission to Congress that it affirm in its 1869 Constitution that the authority by which the State of West Virginia was created out of Virginia territory had indeed been valid, thus giving its consent to the creation of West Virginia retroactively to 1863.

Officers of the Restored Government

Governor

- Francis Harrison Pierpont (1861–1865)

Lieutenant Governors

- Daniel Polsley (1861–1863)

- Leopold Copeland Parker Cowper (1863–1865)

Attorneys General

- James S. Wheat (1861–1863)

- Thomas Russell Bowden (1863–1865)

See also

- Eastern Theater of the American Civil War

- The Confederate government of Kentucky, one of two rival state governments in Kentucky

- The Confederate government of Missouri, one of two rival state governments in Missouri

- The two Virginia gubernatorial elections of 1863: the Union one and the Confederate one

- Virginia in the American Civil War

References

- Forstall, Richard L. (ed.). Population of the States and Counties of the United States: 1790–1990 (PDF) (Report). United States Census Bureau. p. 3. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "Declaration of the People of Virginia Represented in Convention at Wheeling". Wheeling, Virginia. June 13, 1861. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Ambler, Charles H. and Festus P. Summers, West Virginia, the Mountain State, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1958, pg. 200

- "VIRGINIA.; The Restored Government of Virginia—History of the New State of Things". The New York Times. June 26, 1864.

- Martis, Kenneth. Historical Atlas of the United States Congress, 1789–1989. 1989, ISBN 978-0-0292-0170-1, p. 114-116

- Curry, Richard Orr, A House Divided, Statehood Politics & the Copperhead Movement in West Virginia, Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1964, pg. 8

- Ambler, Charles, Francis H. Pierpont: Union War Governor of Virginia and Father of West Virginia, Univ. of North Carolina, 1937, pg. 419, note 36

- "Legislature of the Reorganized Government of Virginia: Extra Session". www.wvculture.org. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- http://www.wvculture.org/hiStory/statehood/statehood11.html

- http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/West_Virginia_Creation_of

- "Lincoln's Dilemma". www.wvculture.org. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- Leonard, Cynthia, M., The General Assembly of Virginia, July 30, 1619-January 11, 1978: A Bicentennial Register of Members, Library of Virginia, 1978, pg. 492 ISBN 0884900088

- Hamilton James Eckenrode, The political history of Virginia during the Reconstruction, Issue 1.

- http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Virginia_Convention_of_1864

Further reading

- Ambler, Charles H. Francis H. Pierpont: Union War Governor and Father of West Virginia (1937), the standard scholarly biography

- Ambler, Charles H. and Festus P. Summers. West Virginia, the Mountain State (2nd ed. 1958) pp 202–6 online

External links

- "A State of Convenience: The Creation of West Virginia". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- "Virginia Convention of 1864". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- West Virginia statehood at West Virginia Archives and History