Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of Oxford and Cambridge, the two oldest, wealthiest, and most famous universities in the United Kingdom. The term is used to refer to them collectively, in contrast to other British universities, and more broadly to describe characteristics reminiscent of them, often with implications of superior social or intellectual status or elitism.[1]

Origins

Although both universities were founded more than eight centuries ago, the term Oxbridge is relatively recent. In William Thackeray's novel Pendennis, published in 1850, the main character attends the fictional Boniface College, Oxbridge. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this is the first recorded instance of the word. Virginia Woolf used it, citing Thackeray, in her 1929 essay A Room of One's Own. By 1957 the term was used in the Times Educational Supplement[2][3] and in Universities Quarterly by 1958.[4]

When expanded, the universities are almost always referred to as "Oxford and Cambridge", the order in which they were founded. A notable exception is Japan's Cambridge and Oxford Society, probably arising from the fact that the Cambridge Club was founded there first, and also had more members than its Oxford counterpart when they amalgamated in 1905.[5]

Meaning

In addition to being a collective term, Oxbridge is often used as shorthand for characteristics the two institutions share:

- They are the two oldest universities in continuous operation in the UK. Both were founded more than 800 years ago,[8][9] and continued as England's only universities (barring short-lived foundations at such as those at Northampton and Durham) until the 19th century. Between them they have educated a large number of Britain's most prominent scientists, writers, and politicians, as well as noted figures in many other fields.[10][11]

- They have established similar institutions and facilities such as printing houses (Oxford University Press and Cambridge University Press), botanical gardens (University of Oxford Botanic Garden and Cambridge University Botanic Garden), museums (the Ashmolean and the Fitzwilliam), legal deposit libraries (the Bodleian and the Cambridge University Library), debating societies (the Oxford Union and the Cambridge Union), and notable comedy groups (The Oxford Revue and The Cambridge Footlights).

- Rivalry between Oxford and Cambridge also has a long history, dating back to around 1209, when Cambridge was founded by scholars taking refuge from hostile Oxford townsmen,[12] and celebrated to this day in varsity matches such as The Boat Race.

- Each has a similar collegiate structure, whereby the university is a co-operative of its constituent colleges, which are responsible for supervisions/tutorials (the principal undergraduate teaching method) and pastoral care.

- They are usually the top-scoring institutions in cross-subject UK university rankings,[13][14][15] so they are targeted by ambitious pupils, parents and schools. Entrance is extremely competitive and some schools promote themselves based on their achievement of Oxbridge offers. Combined, the two universities award over one-sixth of all English full-time research doctorates.[16]

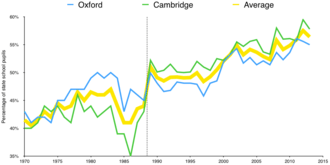

- Oxford and Cambridge have common approaches to undergraduate admissions. Until the mid-1980s, entry was typically by sitting special entrance exams.[17] Applications must be made at least three months earlier than to other UK universities (the deadline for applications to Oxbridge is mid-October whereas the deadline for all other universities, apart from applicants for medicine, is January).[18] Additionally, candidates may not apply to both Oxford and Cambridge in the same year,[19] apart from a few exceptions (e.g., organ scholars).[20] Most candidates achieve, or are predicted to achieve, outstanding results in their final school exams, and consequently interviews are usually used to check whether the course is well suited to the applicant's interests and aptitudes,[21] and to look for evidence of self-motivation, independent thinking, academic potential and ability to learn through the tutorial system.[22]

Criticism

The word Oxbridge may also be used pejoratively: as a descriptor of social class (referring to the professional classes who dominated the intake of both universities at the beginning of the twentieth century),[23] as shorthand for an elite that "continues to dominate Britain's political and cultural establishment"[10][24] and a parental attitude that "continues to see UK higher education through an Oxbridge prism",[25] or to describe a "pressure-cooker" culture that attracts and then fails to support overachievers "who are vulnerable to a kind of self-inflicted stress that can all too often become unbearable"[26] and high-flying state school students who find "coping with the workload very difficult in terms of balancing work and life" and "feel socially out of [their] depth".[27]

The Sutton Trust maintains that the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge recruit disproportionately from 8 schools. They examined published admissions data from 2015 to 2017 and found that 8 schools accounted for 1,310 Oxbridge places during the three years, whereas 2,900 other schools accounted for 1,220.[28]

Access Oxbridge

Access Oxbridge is a non-profit organisation which connects students from low-income backgrounds with undergraduate mentors studying at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.[29] The organisation was set up by Oxford graduate Joe Seddon in response to data from the Sutton Trust suggesting that academically-gifted students from low income backgrounds are underrepresented at highly-selective universities.[30] The mentoring sessions take place in hour-long video calls via the Access Oxbridge app.[31]

Seddon founded Access Oxbridge at the age of 21 and initially funded the organisation from the remnants of his university maintenance grant.[32] Within its first year, Access Oxbridge recruited over 500 undergraduate volunteers to mentor 200 students in Year 12 and 13 from underrepresented backgrounds, resulting in 50 of those students achieving offers to study at Oxford and Cambridge.[33]

In 2019, Seddon relaunched Access Oxbridge as a mobile app.[34] That year, 60 students from the program achieved offers to study at Oxford and Cambridge.[35] In October 2019, Seddon was awarded the Prime Minister's Points of Light award for social impact in education.[36]

Related terms

Other portmanteaus have been coined that extend the term Oxbridge, with different degree of recognition.

The term Loxbridge[37][38][39][40] is also used referring to the golden triangle of London, Oxford, and Cambridge. It was also adopted as the name of the Ancient History conference now known as AMPAH.[41] Doxbridge is another example of this, referring to Durham, Oxford and Cambridge.[42][43][44] Doxbridge was also used for an annual inter-collegiate sports tournament between some of the colleges of Durham, Oxford, Cambridge and York.[45] Meanwhile, Woxbridge is seen in the name of the annual Woxbridge conference between the business schools of Warwick, Oxford and Cambridge.[46]

Thackeray's Pendennis, which introduced the term Oxbridge, also introduced Camford as another combination of the university names – "he was a Camford man and very nearly got the English Prize Poem" – but this term has never achieved the same degree of usage as Oxbridge. Camford is, however, used as the name of a fictional university city in the Sherlock Holmes story The Adventure of the Creeping Man (1923).

See also

References

- "Oxbridge". oed.com (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. 2005.

Originally: a fictional university, esp. regarded as a composite of Oxford and Cambridge. Subsequently also (now esp.): the universities of Oxford and Cambridge regarded together, esp. in contrast to other British universities. adj Of, relating to, characteristic of, or reminiscent of Oxbridge (freq. with implication of superior social or intellectual status

- G.D. Worswick (3 May 1957). "The anatomy of Oxbridge". Times Educational Supplement.

- G.D. Worswick (6 June 1958). "Men's Awards at Oxbridge". Times Educational Supplement.

- A. H. Halsey (1958). "British Universities and Intellectual Life". Universities Quarterly. Turnstile Press. 12 (2): 144. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- Giro Koike (5 April 1995). "Why The "Cambridge & Oxford Society"?". Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- "Oxbridge 'Elitism'" (PDF). parliament.uk. 9 June 2014.

- "Acceptances to Oxford and Cambridge Universities by previous educational establishment". parliament.uk.

- "A brief history of the University". ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- "A Brief History – Early Records". cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- Cadwalladr, Carole (16 March 2008). "Education: It's the clever way to power – Part 1". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- Cadwalladr, Carole (16 March 2008). "Education: It's the clever way to power – Part 2". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- "A Brief History: Early records". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- Watson, Roland. "University Rankings League Table 2009". Good University Guide. London: Times Online. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- "University Rankings League Table". The Sunday Times University Guide. London: Times Online. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- Bernard Kingston (28 April 2008). "League table of UK universities". The Complete University Guide. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- "Research degree qualification rates". Higher Education Funding Council for England. July 2010.

- Walford, Geoffrey (1986). Life in Public Schools. Taylor & Francis. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-416-37180-2. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- "UCAS Students: Important dates for your diary". Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

15 October 2008 Last date for receipt of applications to Oxford University, University of Cambridge and courses in medicine, dentistry and veterinary science or veterinary medicine.

- "UCAS Students FAQs: Oxford or Cambridge". Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

Is it possible to apply to both Oxford University and the University of Cambridge?

- "Organ Awards Information for Prsospective Candidates" (PDF). Faculty of Music, University of Oxford. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

It is possible for a candidate to enter the comparable competition at Cambridge which is scheduled at the same time of year.

- "Cambridge Interviews: the facts" (PDF). University of Cambridge. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- "Interviews at Oxford". University of Oxford. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- Robert David Anderson (2004). European universities from the Enlightenment to 1914. OUP. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-19-820660-6. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- Carole Cadwalladr (16 March 2008). "Oxbridge Blues". The Guardian.

- Eric Thomas (20 January 2004). "Down but not out". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- Elizabeth Davies (21 February 2007). "The over-pressured hothouse that is Oxbridge". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

Two recent deaths have brought the issue of Oxbridge students' mental health back to the surface

- Charlie Boss (2 December 2006). "Why so many state school pupils drop out of Oxbridge". The Spectator. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- Coughlan, Sean (2018). "Oxbridge 'over-recruits from eight schools'". bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- Editor, Rosemary Bennett, Education. "Young mentor secures 60 Oxbridge offers for deprived pupils". ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 31 March 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Montacute, Rebecca (December 2018). "Access to Advantage" (PDF). Sutton Trust.

- Mintz, Luke (17 June 2019). "Can mentor schemes really turn the tables for disadvantaged students applying to Oxbridge?". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Gill, Gurvinder (11 February 2020). "I spent my last £200 getting people into Oxbridge". BBC News. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Editor, Rosemary Bennett, Education. "Oxford graduate Joe Seddon offers key to interview ordeal". ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 31 March 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Student-led outreach initiative Access Oxbridge launches 'groundbreaking' new app". Varsity Online. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Penna, Dominic (12 February 2020). "Want to go to Oxbridge? 5 insider tips for state school students from a 'super mentor'". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Access Oxbridge founder receives Prime Minister's Points of Light award". Varsity Online. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Anon (2018). "The Loxbridge Triangle: Integrating the East-West Arch into the London Mega-region". talks.cam.ac.uk. University of Cambridge.

- "Loxbridge Limited". companieshouse.gov.uk. London: Companies House.

- "Loxbridge tutoring". loxbridge.com.

- Morgan, K. J. (2004). "The research assessment exercise in English universities, 2001". Higher Education. 48 (4): 461–482. doi:10.1023/B:HIGH.0000046717.11717.06. JSTOR 4151567.

- "AMPAH 2003: Annual Meeting of Postgraduates in Ancient History (formerly also known as LOxBridge)". Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- "Doxbridge: a chip on our collective shoulders?". Palatinate. 6 November 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Debate: Rather be at Oxbridge than Doxbridge?". thetab.com. The Tab. 16 January 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Is Doxbridge a thing? We asked Oxbridge students". The Tab. 16 October 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- "The University Sports Tour for Easter 2008". Archived from the original on 2 April 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- "Woxbridge 2011". Conference Website.

| Look up Oxbridge in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |