Nag Hammadi library

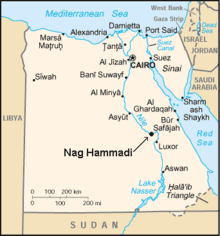

The Nag Hammadi library (also known as the "Chenoboskion Manuscripts" and the "Gnostic Gospels"[lower-alpha 1]) is a collection of early Christian and Gnostic texts discovered near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Influenced by |

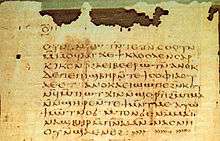

Thirteen leather-bound papyrus codices buried in a sealed jar were found by a local farmer named Muhammed al-Samman.[1] The writings in these codices comprise 52 mostly Gnostic treatises, but they also include three works belonging to the Corpus Hermeticum and a partial translation/alteration of Plato's Republic. In his introduction to The Nag Hammadi Library in English, James Robinson suggests that these codices may have belonged to a nearby Pachomian monastery and were buried after Saint Athanasius condemned the use of non-canonical books in his Festal Letter of 367 A.D. The discovery of these texts significantly influenced modern scholarship's pursuit and knowledge of early Christianity and Gnosticism.

The contents of the codices were written in the Coptic language. The best-known of these works is probably the Gospel of Thomas, of which the Nag Hammadi codices contain the only complete text. After the discovery, scholars recognized that fragments of these sayings attributed to Jesus appeared in manuscripts discovered at Oxyrhynchus in 1898 (P. Oxy. 1), and matching quotations were recognized in other early Christian sources. The written text of the Gospel of Thomas is dated to the second century by most interpreters, but based on much earlier sources.[2] The buried manuscripts date from the 3rd and 4th centuries.

The Nag Hammadi codices are currently housed in the Coptic Museum in Cairo, Egypt.

Discovery

Scholars first became aware of the Nag Hammadi library in 1946. Making careful inquiries from 1947-1950, Jean Doresse discovered that a peasant dug up the texts from a graveyard in the desert, located near tombs from the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt. In the 1970s, James Robinson sought out the peasant in question, identifying him as Muhammad ‘Ali al-Samman. Al-Samman told Robinson a complex story involving a blood feud, cannibalism, digging for fresh soil for agricultural use, and superstitions about a jinn. His mother claimed that she burned some of the manuscripts; Robinson identified these with Codex XII. Robinson gave multiple accounts of this interview, with the number of people present at the discovery ranging from two to eight. [3] Jean Doresse's account contains none of these elements. Recent scholarship has drawn attention to al-Samman's mention of a corpse and a "bed of charcoal" at the site, aspects of the story that were vehemently denied by al-Samman's brother. It is suggested that the library was initially a simple grave robbing and the more fanciful aspects of the story were concocted as a cover story. Burials of books were common in Egypt in the early centuries AD, but if the library was a funerary deposit it conflicts with Robinson's belief that the manuscripts were purposely hidden out of fear of persecution.[4] The blood feud, however, is well attested by multiple sources.[5]

Slowly, most of the tracts came into the hands of Phokion J. Tanos,[6] a Cypriot antiques dealer in Cairo, thereafter being retained by the Department of Antiquities, for fear that they would be sold out of the country. After the revolution in 1952, these texts were handed to the Coptic Museum in Cairo, and declared national property.[7] Pahor Labib, the director of the Coptic Museum at that time, was keen to keep these manuscripts in their country of origin.

Meanwhile, a single codex had been sold in Cairo to a Belgian antiques dealer. After an attempt was made to sell the codex in both New York City and Paris, it was acquired by the Carl Gustav Jung Institute in Zurich in 1951, through the mediation of Gilles Quispel. It was intended as a birthday present to the famous psychologist; for this reason, this codex is typically known as the Jung Codex, being Codex I in the collection.[7]

Jung's death in 1961 resulted in a quarrel over the ownership of the Jung Codex; the pages were not given to the Coptic Museum in Cairo until 1975, after a first edition of the text had been published. The papyri were finally brought together in Cairo: of the 1945 find, eleven complete books and fragments of two others, 'amounting to well over 1000 written pages', are preserved there.[8]

Translation

The first edition of a text found at Nag Hammadi was from the Jung Codex, a partial translation of which appeared in Cairo in 1956, and a single extensive facsimile edition was planned. Due to the difficult political circumstances in Egypt, individual tracts followed from the Cairo and Zurich collections only slowly.

This state of affairs did not change until 1966, with the holding of the Messina Congress in Italy. At this conference, intended to allow scholars to arrive at a group consensus concerning the definition of Gnosticism, James M. Robinson, an expert on religion, assembled a group of editors and translators whose express task was to publish a bilingual edition of the Nag Hammadi codices in English, in collaboration with the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity at the Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, California.

Robinson was elected secretary of the International Committee for the Nag Hammadi Codices, which had been formed in 1970 by UNESCO and the Egyptian Ministry of Culture; it was in this capacity that he oversaw the project. A facsimile edition in twelve volumes was published between 1972 and 1977, with subsequent additions in 1979 and 1984 from the publisher E.J. Brill in Leiden, entitled, The Facsimile Edition of the Nag Hammadi Codices. This made all the texts available for all interested parties to study in some form.

At the same time, in the German Democratic Republic, a group of scholars—including Alexander Böhlig, Martin Krause and New Testament scholars Gesine Schenke, Hans-Martin Schenke and Hans-Gebhard Bethge—were preparing the first German language translation of the find. The last three scholars prepared a complete scholarly translation under the auspices of the Berlin Humboldt University, which was published in 2001.

The James M. Robinson translation was first published in 1977, with the name The Nag Hammadi Library in English, in collaboration between E.J. Brill and Harper & Row. The single-volume publication, according to Robinson, 'marked the end of one stage of Nag Hammadi scholarship and the beginning of another' (from the Preface to the third revised edition). Paperback editions followed in 1981 and 1984, from E.J. Brill and Harper, respectively. A third, completely revised, edition was published in 1988. This marks the final stage in the gradual dispersal of gnostic texts into the wider public arena—the full complement of codices was finally available in unadulterated form to people around the world, in a variety of languages. A cross-reference apparatus for Robinson's translation and the Biblical canon also exists.[9]

Another English edition was published in 1987, by Yale scholar Bentley Layton, called The Gnostic Scriptures: A New Translation with Annotations (Garden City: Doubleday & Co., 1987). The volume included new translations from the Nag Hammadi Library, together with extracts from the heresiological writers, and other gnostic material. It remains, along with The Nag Hammadi Library in English, one of the more accessible volumes of translations of the Nag Hammadi find. It includes extensive historical introductions to individual gnostic groups, notes on translation, annotations to the text, and the organization of tracts into clearly defined movements.

Not all scholars agree that the entire library should be considered Gnostic. Paterson Brown has argued that the three Nag Hammadi Gospels of Thomas, Philip and Truth cannot be so labeled, since each, in his opinion, may explicitly affirm the basic reality and sanctity of incarnate life, which Gnosticism by definition considers illusory.[10]

Complete list of codices found in Nag Hammadi

See #External links for complete list of manuscripts

- Codex I (also known as The Jung Codex):

- The Prayer of the Apostle Paul

- The Apocryphon of James (also known as the Secret Book of James)

- The Gospel of Truth

- The Treatise on the Resurrection

- The Tripartite Tractate

- Codex II:

- The Apocryphon of John

- The Gospel of Thomas a sayings gospel

- The Gospel of Philip

- The Hypostasis of the Archons

- On the Origin of the World

- The Exegesis on the Soul

- The Book of Thomas the Contender

- Codex III:

- The Apocryphon of John

- Holy Book of the Great Invisible Spirit named The Gospel of the Egyptians

- Eugnostos the Blessed

- The Sophia of Jesus Christ

- The Dialogue of the Saviour

- Codex IV:

- The Apocryphon of John

- Holy Book of the Great Invisible Spirit named The Gospel of the Egyptians

- Codex V:

- Codex VI:

- The Acts of Peter and the Twelve Apostles

- The Thunder, Perfect Mind

- Authoritative Teaching

- The Concept of Our Great Power

- Republic by Plato – The original is not gnostic, but the Nag Hammadi library version is heavily modified with then-current gnostic concepts.

- The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth – a Hermetic treatise

- The Prayer of Thanksgiving (with a hand-written note) – a Hermetic prayer

- Asclepius 21–29 – another Hermetic treatise

- Codex VII:

- Codex VIII:

- Codex IX:

- Melchizedek

- The Thought of Norea

- The Testimony of Truth

- Codex X:

- Codex XI:

- The Interpretation of Knowledge

- A Valentinian Exposition, On the Anointing, On Baptism (A and B) and On the Eucharist (A and B)

- Allogenes

- Hypsiphrone

- Codex XII

- The Sentences of Sextus

- The Gospel of Truth

- Fragments

- Codex XIII:

- Trimorphic Protennoia

- On the Origin of the World

The so-called "Codex XIII" is not a codex, but rather the text of Trimorphic Protennoia, written on "eight leaves removed from a thirteenth book in late antiquity and tucked inside the front cover of the sixth." (Robinson, NHLE, p. 10) Only a few lines from the beginning of Origin of the World are discernible on the bottom of the eighth leaf.

Dating

Although the manuscripts discovered at Nag Hammadi are generally dated to the 4th century, there is some debate regarding the original composition of the texts.[11]

- The Gospel of Thomas is held by most to be the earliest of the "gnostic" gospels composed. Scholars generally date the text to the early-mid 2nd century.[12] The Gospel of Thomas, it is often claimed, has some gnostic elements but lacks the full gnostic cosmology. However, even the description of these elements as "gnostic" is based mainly upon the presupposition that the text as a whole is a "gnostic" gospel, and this idea itself is based upon little other than the fact that it was found along with gnostic texts at Nag Hammadi.[13] Some scholars including Nicholas Perrin argue that Thomas is dependent on the Diatessaron, which was composed shortly after 172 by Tatian in Syria.[14] A minority view contends for an early date of perhaps 50, citing a relationship to the hypothetical Q document among other reasons.[15]

- The Gospel of Truth[16] and the teachings of the Pistis Sophia can be approximately dated to the early 2nd century as they were part of the original Valentinian school, though the gospel itself is 3rd century.

- Documents with a Sethian influence (like the Gospel of Judas, or outright Sethian like Coptic Gospel of the Egyptians) can be dated substantially later than 40 and substantially earlier than 250; most scholars giving them a 2nd-century date.[17] More conservative scholars using the traditional dating method would argue in these cases for the early 3rd century.

- Some gnostic gospels (for example Trimorphic Protennoia) make use of fully developed Neoplatonism and thus need to be dated after Plotinus in the 3rd century.[18][19]

See also

Notes

- The texts are referred to as the "Gnostic Gospels" after Elaine Pagels' 1979 book of the same name, but the term also has a more generic meaning.

References

- Marvin Meyer and James M. Robinson, The Nag Hammadi Scriptures: The International Edition. HarperOne, 2007. pp 2-3. ISBN 0-06-052378-6

- Van Voorst, Robert (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. p. 189.

- Goodacre, Mark (14 May 2013). "How Reliable is the Story of the Nag Hammadi Discovery?". Journal for the Study of the New Testament. 35 (4): 303–322. doi:10.1177/0142064X13482243.

- Lewis; Blount (2014). "Rethinking the Origins of the Nag Hammadi Codices". Journal of Biblical Literature. 133 (2): 399. doi:10.15699/jbibllite.133.2.399.

- Burns, Dylan Michael (7 May 2016). "Telling Nag Hammadi's Egyptian Stories". Bulletin for the Study of Religion. 45 (2): 5–11. doi:10.1558/bsor.v45i2.28176.

- The Gnostic Discoveries: The Impact of the Nag Hammadi Library; also known as Phocion J(ean) Tano, cf. Wikidata entry

- Robinson, James M. ed., The Nag Hammadi Library, revised edition. HarperCollins, San Francisco, 1990.

- (Markschies, Gnosis: An Introduction, 49)

- Clontz, T.E. and J., The Comprehensive New Testament, Cornerstone Publications (2008), ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5

- Essay on the Ecumenical Coptic Project website, from which the requisite Coptic font may be downloaded. Archived December 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Bock, Darrell (2006). The Missing Gospels. Nelson Books. p. 6.

- Ehrman, Bart (2003). Lost Christianities. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. xi–xii.

- Davies, Stevan L., The Gospel of Thomas and Christian Wisdom, 1983, pp. 21–22.

- Nicholas Perrin, "Thomas: The Fifth Gospel?," Journal of The Evangelical Theological Society 49 (March 2006): 66-/80

- Koester, Helmut; Lambdin (translator), Thomas O. (1996). "The Gospel of Thomas". In Robinson, James MacConkey (ed.). The Nag Hammadi Library in English (Revised ed.). Leiden, New York, Cologne: E. J. Brill. p. 125. ISBN 90-04-08856-3.

- But the followers of Valentinus, putting away all fear, bring forward their own compositions and boast that they have more Gospels than really exist. Indeed their audacity has gone so far that they entitle their recent composition the Gospel of Truth Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses (3.11.9)"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-06-08. Retrieved 2007-05-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Gnosticism and Platonism: The Platonizing Sethian texts from Nag Hammadi in their Relation to Later Platonic Literature Archived 2007-06-22 at the Wayback Machine, John D Turner, ISBN 0-7914-1338-1.

- "Sethian Gnosticism: A Literary History," Archived 2007-07-06 at the Wayback Machine in Nag Hammadi, Gnosticism and Early Christianity, pp. 55–86 ISBN 0-913573-16-7

- The National Geographic Society dates the gospel of Judas originally to mid 2nd century "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-04-18. Retrieved 2015-04-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) and the copy we possess 220–340

- Plotinus, a native of Lycopolis in Egypt, who lived from 205 to 270 was the first systematic philosopher of [Neo-Platonism], Turner, William (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 10}. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 375.

Further reading

- Layton, Bentley (1987). The Gnostic Scriptures. SCM Press. ISBN 0-334-02022-0. (526 pages)

- Markschies, Christoph (trans. John Bowden) (2000). Gnosis: An Introduction. T & T Clark. ISBN 0-567-08945-2. (145 pages)

- Pagels, Elaine (1979). The Gnostic Gospels. Random House. ISBN 0-679-72453-2. (182 pages)

- Robinson, James (1988). The Nag Hammadi Library in English. ISBN 0-06-066934-9. (549 pages)

- Robinson, James M., 1979 "The discovery of the Nag Hammadi codices," in Biblical Archaeology vol. 42, pp. 206–224.

- Tuckett, Christopher M. (1986). Nag Hammadi and the Gospel Tradition: Synoptic Tradition in the Nag Hammadi Library. T & T Clark. ISBN 0-567-09364-6. (206 pages)

- Yamauchi, Edwin M. (1983). Pre-Christian Gnosticism : A Survey of the Proposed Evidences. ISBN 0-8010-9919-6. (278 pages)

- Yamauchi, Edwin M., "Pre-Christian Gnosticism in the Nag Hammadi Texts?," in Church History vol. 48, pp. 129–141.

- Franzmann, Majella, 1996 Jesus in the Nag Hammadi Writings, T & T Clark International. ISBN 056704470X. (293 pages)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nag Hammadi library |

- Nag Hammadi Archive in the Claremont Colleges Digital Library

- The Nag Hammadi Library – Complete texts at The Gnostic Society Library

- The Gospel of Thomas – Multiple translations and resources.

- How the manuscripts were found - A complete list of the manuscripts can be found here.

- Jung Codex