Biblical canon

A biblical canon or canon of scripture[1] is a set of texts (or "books") which a particular religious community regards as authoritative scripture. The English word "canon" comes from the Greek κανών, meaning "rule" or "measuring stick". Christians were the first to use the term in reference to scripture, but Eugene Ulrich regards the notion as Jewish.[2][3]

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Perspectives |

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

Most of the canons listed below are considered by adherents "closed" (i.e., books cannot be added or removed),[4] reflecting a belief that public revelation has ended and thus some person or persons can gather approved inspired texts into a complete and authoritative canon, which scholar Bruce Metzger defines as "an authoritative collection of books".[5] In contrast, an "open canon", which permits the addition of books through the process of continuous revelation, Metzger defines as "a collection of authoritative books".

These canons have developed through debate and agreement on the part of the religious authorities of their respective faiths and denominations. Christians have a range of interpretations of the Bible, from taking it completely as literal history dictated by God to divinely inspired stories that teach important moral and spiritual lessons, to human creations recording encounters with or thoughts about the divine. Some books, such as the Jewish–Christian gospels, have been excluded from various canons altogether, but many disputed books—considered non-canonical or even apocryphal by some—are considered to be biblical apocrypha or deuterocanonical or fully canonical by others. Differences exist between the Jewish Tanakh and Christian biblical canons, although the Jewish Tanakh did form the basis for the Christian Old Testament, and between the canons of different Christian denominations. In some cases where varying strata of scriptural inspiration have accumulated, it becomes prudent to discuss texts that only have an elevated status within a particular tradition. This becomes even more complex when considering the open canons of the various Latter Day Saint sects and the scriptural revelations purportedly given to several leaders over the years within that movement.

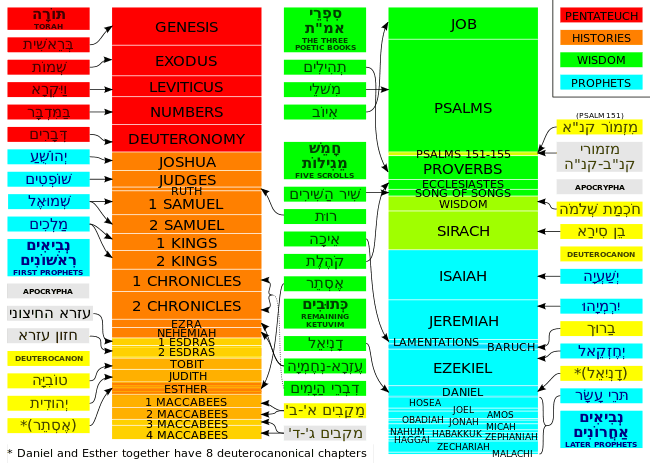

Different religious groups include different books in their biblical canons, in varying orders, and sometimes divide or combine books. The Jewish Tanakh (sometimes called the Hebrew Bible) contains 24 books divided into three parts: the five books of the Torah ("teaching"); the eight books of the Nevi'im ("prophets"); and the eleven books of Ketuvim ("writings"). It is composed mainly in Biblical Hebrew, and its Septuagint is the main textual source for the Christian Greek Old Testament.[6]

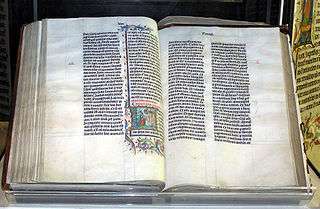

Christian Bibles range from the 73 books of the Catholic Church canon, the 66 books of the canon of some denominations or the 80 books of the canon of other denominations of the Protestant Church, to the 81 books of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church canon. The first part of Christian Bibles is the Greek Old Testament, which contains, at minimum, the above 24 books of the Tanakh but divided into 39 (Protestant) or 46 (Catholic) books and ordered differently. The second part is the Greek New Testament, containing 27 books; the four canonical gospels, Acts of the Apostles, 21 Epistles or letters and the Book of Revelation.

The Catholic Church and Eastern Christian churches hold that certain deuterocanonical books and passages are part of the Old Testament canon. The Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Assyrian Christian churches may have minor differences in their lists of accepted books. The list given here for these churches is the most inclusive: if at least one Eastern church accepts the book it is included here. The King James Bible—which has been called "the most influential version of the most influential book in the world, in what is now its most influential language" and which in the United States is the most used translation, is still considered a standard among Protestant churches and used liturgically in the Orthodox Church in America—contains 80 books: 39 in its Old Testament, 14 in its Apocrypha, and 27 in its New Testament.

Jewish canons

Rabbinic Judaism

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other religions |

|

Related topics |

|

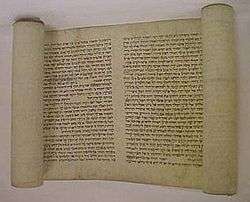

Rabbinic Judaism (Hebrew: יהדות רבנית) recognizes the twenty-four books of the Masoretic Text, commonly called the Tanakh (Hebrew: תַּנַ"ךְ) or Hebrew Bible.[7] Evidence suggests that the process of canonization occurred between 200 BC and 200 AD, and a popular position is that the Torah was canonized c. 400 BC, the Prophets c. 200 BC, and the Writings c. 100 AD[8] perhaps at a hypothetical Council of Jamnia—however, this position is increasingly criticised by modern scholars.[9][10][11][12][13][14] According to Marc Zvi Brettler, the Jewish scriptures outside the Torah and the Prophets were fluid, different groups seeing authority in different books.[15]

The Book of Deuteronomy includes a prohibition against adding or subtracting (4:2, 12:32) which might apply to the book itself (i.e. a "closed book", a prohibition against future scribal editing) or to the instruction received by Moses on Mt. Sinai.[16] The book of 2 Maccabees, itself not a part of the Jewish canon, describes Nehemiah (c. 400 BC) as having "founded a library and collected books about the kings and prophets, and the writings of David, and letters of kings about votive offerings" (2:13–15).

The Book of Nehemiah suggests that the priest-scribe Ezra brought the Torah back from Babylon to Jerusalem and the Second Temple (8–9) around the same time period. Both I and II Maccabees suggest that Judas Maccabeus (c. 167 BC) likewise collected sacred books (3:42–50, 2:13–15, 15:6–9), indeed some scholars argue that the Jewish canon was fixed by the Hasmonean dynasty.[17] However, these primary sources do not suggest that the canon was at that time closed; moreover, it is not clear that these sacred books were identical to those that later became part of the canon.

The Great Assembly, also known as the Great Synagogue, was, according to Jewish tradition, an assembly of 120 scribes, sages, and prophets, in the period from the end of the Biblical prophets to the time of the development of Rabbinic Judaism, marking a transition from an era of prophets to an era of Rabbis. They lived in a period of about two centuries ending c. 70 AD. Among the developments in Judaism that are attributed to them are the fixing of the Jewish Biblical canon, including the books of Ezekiel, Daniel, Esther, and the Twelve Minor Prophets; the introduction of the triple classification of the oral Torah, dividing its study into the three branches of midrash, halakot, and aggadot; the introduction of the Feast of Purim; and the institution of the prayer known as the Shemoneh 'Esreh as well as the synagogal prayers, rituals, and benedictions.

In addition to the Tanakh, mainstream Rabbinic Judaism considers the Talmud (Hebrew: תַּלְמוּד ) to be another central, authoritative text. It takes the form of a record of rabbinic discussions pertaining to Jewish law, ethics, philosophy, customs, and history. The Talmud has two components: the Mishnah (c. 200 AD), the first written compendium of Judaism's oral Law; and the Gemara (c. 500 AD), an elucidation of the Mishnah and related Tannaitic writings that often ventures onto other subjects and expounds broadly on the Tanakh. There are numerous citations of Sirach within the Talmud, even though the book was not ultimately accepted into the Hebrew canon.

The Talmud is the basis for all codes of rabbinic law and is often quoted in other rabbinic literature. Certain groups of Jews, such as the Karaites, do not accept the oral Law as it is codified in the Talmud and only consider the Tanakh to be authoritative.

Beta Israel

Ethiopian Jews—also known as Beta Israel (Ge'ez: ቤተ እስራኤል—Bēta 'Isrā'ēl)—possess a canon of scripture that is distinct from Rabbinic Judaism. Mäṣḥafä Kedus (Holy Scriptures) is the name for the religious literature of these Jews, which is written primarily in Ge'ez. Their holiest book, the Orit, consists of the Pentateuch, as well as Joshua, Judges, and Ruth. The rest of the Ethiopian Jewish canon is considered to be of secondary importance. It consists of the remainder of the Hebrew canon—with the possible exception of the Book of Lamentations—and various deuterocanonical books. These include Sirach, Judith, Tobit, 1 and 2 Esdras, 1 and 4 Baruch, the three books of Meqabyan, Jubilees, Enoch,[note 1] the Testament of Abraham, the Testament of Isaac, and the Testament of Jacob. The latter three patriarchal testaments are distinct to this scriptural tradition.[note 2]

A third tier of religious writings that are important to Ethiopian Jews, but are not considered to be part of the canon, include the following: Nagara Muse (The Conversation of Moses), Mota Aaron (Death of Aaron), Mota Muse (Death of Moses), Te'ezaza Sanbat (Precepts of Sabbath), Arde'et (Students), the Apocalypse of Gorgorios, Mäṣḥafä Sa'atat (Book of Hours), Abba Elias (Father Elija), Mäṣḥafä Mäla'əkt (Book of Angels), Mäṣḥafä Kahan (Book of Priests), Dərsanä Abrəham Wäsara Bägabs (Homily on Abraham and Sarah in Egypt), Gadla Sosna (The Acts of Susanna), and Baqadāmi Gabra Egzi'abḥēr (In the Beginning God Created).

In addition to these, Zëna Ayhud (the Ethiopic version of Josippon) and the sayings of various fālasfā (philosophers) are sources that are not necessarily considered holy, but nonetheless have great influence.

Samaritan canon

Another version of the Torah, in the Samaritan alphabet, also exists. This text is associated with the Samaritans (Hebrew: שומרונים; Arabic: السامريون), a people of whom the Jewish Encyclopedia states: "Their history as a distinct community begins with the taking of Samaria by the Assyrians in 722 BC."[18]

.jpg)

The Samaritan Pentateuch's relationship to the Masoretic Text is still disputed. Some differences are minor, such as the ages of different people mentioned in genealogy, while others are major, such as a commandment to be monogamous, which only appears in the Samaritan version. More importantly, the Samaritan text also diverges from the Masoretic in stating that Moses received the Ten Commandments on Mount Gerizim—not Mount Sinai—and that it is upon this mountain (Gerizim) that sacrifices to God should be made—not in Jerusalem. Scholars nonetheless consult the Samaritan version when trying to determine the meaning of text of the original Pentateuch, as well as to trace the development of text-families. Some scrolls among the Dead Sea scrolls have been identified as proto-Samaritan Pentateuch text-type.[19] Comparisons have also been made between the Samaritan Torah and the Septuagint version.

Samaritans consider the Torah to be inspired scripture, but do not accept any other parts of the Bible—probably a position also held by the Sadducees.[20] They did not expand their canon by adding any Samaritan compositions. There is a Samaritan Book of Joshua; however, this is a popular chronicle written in Arabic and is not considered to be scripture. Other non-canonical Samaritan religious texts include the Memar Markah (Teaching of Markah) and the Defter (Prayerbook)—both from the 4th century or later.[21]

The people of the remnants of the Samaritans in modern-day Israel/Palestine retain their version of the Torah as fully and authoritatively canonical.[18] They regard themselves as the true "guardians of the Law." This assertion is only re-enforced by the claim of the Samaritan community in Nablus (an area traditionally associated with the ancient city of Shechem) to possess the oldest existing copy of the Torah—one that they believe to have been penned by Abisha, a grandson of Aaron.[22]

Christian canons

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early Church

Earliest Christian communities

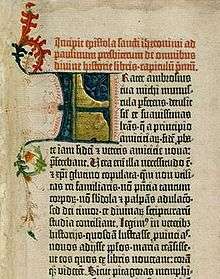

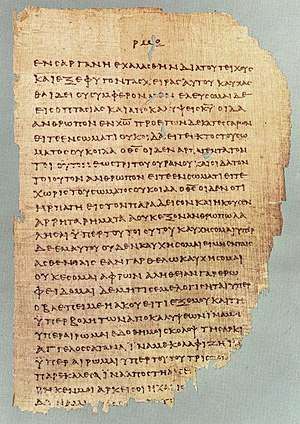

The Early Church used the Old Testament, namely the Septuagint (LXX)[23] among Greek speakers, with a canon perhaps as found in the Bryennios List or Melito's canon. The Apostles did not otherwise leave a defined set of new scriptures; instead, the New Testament developed over time.

Writings attributed to the apostles circulated among the earliest Christian communities. The Pauline epistles were circulating in collected forms by the end of the 1st century AD. Justin Martyr, in the early 2nd century, mentions the "memoirs of the Apostles", which Christians (Greek: Χριστιανός) called "gospels", and which were considered to be authoritatively equal to the Old Testament.[24]

Marcion's list

Marcion of Sinope was the first Christian leader in recorded history (though later considered heretical) to propose and delineate a uniquely Christian canon[25] (c. AD 140). This included 10 epistles from St. Paul, as well as a version of the Gospel of Luke, which today is known as the Gospel of Marcion. By doing this, he established a particular way of looking at religious texts that persists in Christian thought today.[26]

After Marcion, Christians began to divide texts into those that aligned well with the "canon" (measuring stick) of accepted theological thought and those that promoted heresy. This played a major role in finalizing the structure of the collection of works called the Bible. It has been proposed that the initial impetus for the proto-orthodox Christian project of canonization flowed from opposition to the list produced by Marcion.[26]

Apostolic Fathers

A four-gospel canon (the Tetramorph) was asserted by Irenaeus in the following quote: "It is not possible that the gospels can be either more or fewer in number than they are. For, since there are four-quarters of the earth in which we live, and four universal winds, while the church is scattered throughout all the world, and the 'pillar and ground' of the church is the gospel and the spirit of life, it is fitting that she should have four pillars breathing out immortality on every side, and vivifying men afresh ... Therefore the gospels are in accord with these things ... For the living creatures are quadriform and the gospel is quadriform ... These things being so, all who destroy the form of the gospel are vain, unlearned, and also audacious; those [I mean] who represent the aspects of the gospel as being either more in number than as aforesaid, or, on the other hand, fewer."[27]

By the early 3rd century, Christian theologians like Origen of Alexandria may have been using—or at least were familiar with—the same 27 books found in modern New Testament editions, though there were still disputes over the canonicity of some of the writings (see also Antilegomena).[28] Likewise by 200, the Muratorian fragment shows that there existed a set of Christian writings somewhat similar to what is now the New Testament, which included four gospels and argued against objections to them.[29] Thus, while there was a good measure of debate in the Early Church over the New Testament canon, the major writings were accepted by almost all Christians by the middle of the 3rd century.[30]

Eastern Church

Alexandrian Fathers

Origen of Alexandria (184/85–253/54), an early scholar involved in the codification of the Biblical canon, had a thorough education both in Christian theology and in pagan philosophy, but was posthumously condemned at the Second Council of Constantinople in 553 since some of his teachings were considered to be heresy. Origen's canon included all of the books in the current New Testament canon except for four books: James, 2nd Peter, and the 2nd and 3rd epistles of John.[31]

He also included the Shepherd of Hermas which was later rejected. The religious scholar Bruce Metzger described Origen's efforts, saying "The process of canonization represented by Origen proceeded by way of selection, moving from many candidates for inclusion to fewer."[32] This was one of the first major attempts at the compilation of certain books and letters as authoritative and inspired teaching for the Early Church at the time, although it is unclear whether Origen intended for his list to be authoritative itself.

In his Easter letter of 367, Patriarch Athanasius of Alexandria gave a list of exactly the same books that would become the New Testament–27 book–proto-canon,[33] and used the phrase "being canonized" (kanonizomena) in regard to them.[34] Athanasius also included the Book of Baruch, as well as the Letter of Jeremiah, in his Old Testament canon. However, from this canon, he omitted the Book of Esther.

Eastern canons

The Eastern Churches had, in general, a weaker feeling than those in the West for the necessity of making sharp delineations with regard to the canon. They were more conscious of the gradation of spiritual quality among the books that they accepted (for example, the classification of Eusebius, see also Antilegomena) and were less often disposed to assert that the books which they rejected possessed no spiritual quality at all. For example, the Trullan Synod of 691–692, which Pope Sergius I (in office 687–701) rejected[35] (see also Pentarchy), endorsed the following lists of canonical writings: the Apostolic Canons (c. 385), the Synod of Laodicea (c. 363), the Third Synod of Carthage (c. 397), and the 39th Festal Letter of Athanasius (367).[36] And yet, these lists do not agree. Similarly, the New Testament canons of the Syriac, Armenian, Georgian, Egyptian Coptic and Ethiopian Churches all have minor differences, yet five of these Churches are part of the same communion and hold the same theological beliefs.[37] The Revelation of John is said to be one of the most uncertain books; it was not translated into Georgian until the 10th century, and it has never been included in the official lectionary of the Eastern Orthodox Church, whether in Byzantine or modern times.

Western Church

Latin Fathers

The first Council that accepted the present Catholic canon (the Canon of Trent of 1546) may have been the Synod of Hippo Regius, held in North Africa in 393. A brief summary of the acts was read at and accepted by the Council of Carthage (397) and also the Council of Carthage (419).[38] These Councils took place under the authority of St. Augustine (354–430), who regarded the canon as already closed.[39] Pope Damasus I's Council of Rome in 382 (if the Decretum Gelasianum is correctly associated with it) issued a biblical canon identical to that mentioned above.[33] If not, the list is at least a 6th-century compilation.[40] Likewise, Damasus' commissioning of the Latin Vulgate edition of the Bible, c. 383, proved instrumental in the fixation of the canon in the West.[41]

In a letter (c. 405) to Exsuperius of Toulouse, a Gallic bishop, Pope Innocent I mentioned the sacred books that were already received in the canon.[42] When these bishops and Councils spoke on the matter, however, they were not defining something new, but instead "were ratifying what had already become the mind of the Church".[43][44][45] Thus from the 4th century there existed unanimity in the West concerning the New Testament canon (as it is today,[46] with the exception of the Book of Revelation). In the 5th century the East too, with a few exceptions, came to accept the Book of Revelation and thus came into harmony on the matter of the New Testament canon.[47]

As the canon crystallised, non-canonical texts fell into relative disfavour and neglect.[48]

Luther's canon

Martin Luther (1483–1546) moved seven Old Testament books (Tobit, Judith, 1–2 Maccabees, Book of Wisdom, Sirach, and Baruch) into a section he called the Apocrypha. To refer to these books without calling them "apocrypha", the Catholic Church later referred to them as the Deuterocanonicals—while still accepting their full canonicity.

Luther removed the books of Hebrews, James, Jude and Revelation from the canon (partially because some were perceived to go against certain Protestant doctrines such as sola scriptura and sola fide),[49] while defenders of Luther cite previous scholarly precedent and support as the justification for his marginalization of certain books,[50] including 2 Maccabees [51] However, Luther's smaller canon was not fully accepted in Protestantism, though apocryphal books are ordered last in the German-language Luther Bible to this day.

Canons of various Christian traditions

Final dogmatic articulations of the canons were made at the Council of Trent of 1546 for Roman Catholicism,[52] the Thirty-Nine Articles of 1563 for the Church of England, the Westminster Confession of Faith of 1647 for Calvinism, and the Synod of Jerusalem of 1672 for the Eastern Orthodox. Other traditions, while also having closed canons, may not be able to point to an exact year in which their canons were complete. The following tables reflect the current state of various Christian canons.

Old Testament

All of the major Christian traditions accept the books of the Hebrew protocanon in its entirety as divinely inspired and authoritative, in various ways and degrees.

Another set of books, largely written during the intertestamental period, are called the biblical apocrypha ("hidden things") by Protestants, the deuterocanon ("second canon") by Catholics, and the deuterocanon or anagignoskomena ("worthy of reading") by Orthodox. These are works recognized by the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox Churches as being part of scripture (and thus deuterocanonical rather than apocryphal), but Protestants do not recognize them as divinely inspired. Orthodox differentiate scriptural books by omitting these (and others) from corporate worship and from use as a sole basis for doctrine. Some Protestant Bibles—especially the English King James Bible and the Lutheran Bible—include an "Apocrypha" section.

Many denominations recognize deuterocanonical books as good, but not on the level of the other books of the Bible. Anglicanism considers the apocrypha worthy of being "read for example of life" but not to be used "to establish any doctrine."[53] Luther made a parallel statement in calling them: "not considered equal to the Holy Scriptures, but...useful and good to read."[54]

The difference in canons derives from the difference in the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint. Books found in both the Hebrew and the Greek are accepted by all denominations, and by Jews, these are the protocanonical books. Catholics and Orthodox also accept those books present in manuscripts of the Septuagint, an ancient Greek translation of the Old Testament with great currency among the Jews of the ancient world, with the coda that Catholics consider 3 Esdras and 3 Maccabees apocryphal.

Most quotations of the Old Testament in the New Testament, differing by varying degrees from the Masoretic Text, are taken from the Septuagint. Daniel was written several hundred years after the time of Ezra, and since that time several books of the Septuagint have been found in the original Hebrew, in the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Cairo Geniza, and at Masada, including a Hebrew text of Sirach (Qumran, Masada) and an Aramaic text of Tobit (Qumran); the additions to Esther and Daniel are also in their respective Semitic languages.

The unanimous consensus of modern (and ancient) scholars consider several other books, including 1 Maccabees and Judith, to have been composed in Hebrew or Aramaic. Opinion is divided on the book of Baruch, while it is acknowledged that the Letter of Jeremiah, the Wisdom of Solomon, and 2 Maccabees are originally Greek compositions.

Some books listed here, like the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs for the Armenian Apostolic Church, may have once been a vital part of a Biblical tradition, may even still hold a place of honor, but are no longer considered to be part of the Bible. Other books, like the Prayer of Manasseh for the Roman Catholic Church, may have been included in manuscripts, but never really attained a high level of importance within that particular tradition. The levels of traditional prominence for others, like Psalms 152–155 and the Psalms of Solomon of the Syriac churches, remain unclear.

In the Oriental Orthodox Tewahedo canon, the books of Lamentations, Jeremiah, and Baruch, as well as the Letter of Jeremiah and 4 Baruch, are all considered canonical by the Orthodox Tewahedo Churches. However, it is not always clear as to how these writings are arranged or divided. In some lists, they may simply fall under the title "Jeremiah", while in others, they are divided in various ways into separate books. Moreover, the book of Proverbs is divided into two books—Messale (Prov. 1–24) and Tägsas (Prov. 25–31).

Additionally, while the books of Jubilees and Enoch are fairly well-known among western scholars, 1, 2, and 3 Meqabyan are not. The three books of Meqabyan are often called the "Ethiopian Maccabees", but are completely different in content from the books of Maccabees that are known or have been canonized in other traditions. Finally, the Book of Joseph ben Gurion, or Pseudo-Josephus, is a history of the Jewish people thought to be based upon the writings of Josephus.[note 3] The Ethiopic version (Zëna Ayhud) has eight parts and is included in the Orthodox Tewahedo broader canon.[note 4][55]

Additional books accepted by the Syriac Orthodox Church (due to inclusion in the Peshitta):

- 2 Baruch with the Letter of Baruch (only the letter has achieved canonical status)

- Psalms 152–155 (not canonical)

The Ethiopian Tewahedo church accepts all of the deuterocanonical books of Catholicism and anagignoskomena of Eastern Orthodoxy except for the four Books of Maccabees.[56] It accepts the 39 protocanonical books along with the following books, called the "narrow canon".[57] The enumeration of books in the Ethiopic Bible varies greatly between different authorities and printings.[58]

- 4 Baruch or the Paralipomena of Jeremiah

- 1 Enoch

- Jubilees

- First, Second and Third Books of Ethiopian Maccabees

- The Ethiopian broader Biblical Canon

Protestants and Catholics[6] use the Masoretic Text of the Jewish Tanakh as the textual basis for their translations of the protocanonical books (those accepted as canonical by both Jews and all Christians), with various changes derived from a multiplicity of other ancient sources (such as the Septuagint, the Vulgate, the Dead Sea Scrolls, etc.), while generally using the Septuagint and Vulgate, now supplemented by the ancient Hebrew and Aramaic manuscripts, as the textual basis for the deuterocanonical books.

The Eastern Orthodox use the Septuagint (translated in the 3rd century BCE) as the textual basis for the entire Old Testament in both protocanonical and deuteroncanonical books—to use both in the Greek for liturgical purposes, and as the basis for translations into the vernacular.[59][60] Most of the quotations (300 of 400) of the Old Testament in the New Testament, while differing more or less from the version presented by the Masoretic text, align with that of the Septuagint.[61]

Diagram of the development of the Old Testament

Table

The order of some books varies among canons.

| Western tradition | Eastern Orthodox tradition | Oriental Orthodox tradition | Assyrian Eastern tradition | Judaism | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Books | Protestant [O 1] |

Lutheran | Anglican | Roman Catholic [O 2] |

Greek Orthodox | Slavonic Orthodox | Georgian Orthodox | Armenian Apostolic[O 3] | Syriac Orthodox | Coptic Orthodox | Orthodox Tewahedo[O 4] | Assyrian Church of the East | the Hebrew Bible |

| Pentateuch | Torah | ||||||||||||

| Genesis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Bereshit |

| Exodus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Shemot |

| Leviticus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Vayikra |

| Numbers | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Vayikra |

| Deuteronomy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Devarim |

| History | Nevi'im | ||||||||||||

| Joshua | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Josue | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Yehoshua |

| Judges | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Shofetim |

| Ruth | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Rut (part of Ketuvim) |

| 1 and 2 Samuel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes 1 and 2 Kings | Yes 1 and 2 Kingdoms | Yes 1 and 2 Kingdoms | Yes 1 and 2 Kingdoms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Shemuel |

| 1 and 2 Kings | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes 3 and 4 Kings | Yes 3 and 4 Kingdoms | Yes 3 and 4 Kingdoms | Yes 3 and 4 Kingdoms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Melakhim |

| 1 and 2 Chronicles | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes 1 and 2 Paralipomenon | Yes 1 and 2 Paralipomenon | Yes 1 and 2 Paralipomenon | Yes 1 and 2 Paralipomenon | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Divrei Hayamim (part of Ketuvim) |

| Prayer of Manasseh | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha)[O 5] | No (Apocrypha)[O 5] | No – inc. in some mss. | Yes (?) (part of Odes)[O 6] | Yes (?) (part of Odes)[O 6] | Yes (?) (part of Odes)[O 6] | Yes (?) | Yes (?) | Yes[62] | Yes[63] | Yes (?) | No |

| Ezra (1 Ezra) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes 1 Esdras | Yes Esdras B' | Yes 1 Esdras | Yes 1 Ezra | Yes 1 Ezra | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Ezra–Nehemiah (part of Ketuvim) |

| Nehemiah (2 Ezra) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes 2 Esdras | Yes Esdras Γ' or Neemias | Yes Neemias | Yes Neemias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 1 Esdras (3 Ezra) | No − inc. in some eds. | No | No 1 Esdras (Apocrypha) | No 3 Esdras (inc. in some mss.) | Yes Esdras A' | Yes 2 Esdras | Yes 2 Ezra | Yes 2 Ezra[O 7] | No (?) – inc. in some mss. | No – inc. in some mss. | Yes Ezra Kali | No (?) – inc. in some mss. | No |

| 2 Esdras 3–14 (4 Ezra or Apocalypsis of Esdras)[O 8] | No − inc. in some eds. | No | No 2 Esdras (Apocrypha) | No 4 Esdras (inc. in some mss.) | No (Greek ms. lost)[O 9] | No 3 Esdras (appendix) | Yes (?) 3 Ezra | Yes 3 Ezra [O 7] | No (?) – inc. in some mss. | No – inc. in some mss. | Yes Ezra Sutu'el | No (?) – inc. in some mss. | No |

| 2 Esdras 1–2; 15–16 (5 and 6 Ezra or Apocalypsis of Esdras)[O 8] | No − inc. in some eds. | No | No (part of 2 Esdras apocryphon) | No (part of 4 Esdras) | No (Greek ms.)[O 10] | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Esther[O 11] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Ester (part of Ketuvim) |

| Additions to Esther | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Tobit (Tobias) | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Judith | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 1 Maccabees [O 12] | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes 1 Machabees | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 2 Maccabees[O 12] | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes 2 Machabees | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 3 Maccabees | No − inc. in some eds. | No | No − inc. in some eds. | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[O 7] | Yes | No – inc. in some mss. | No | Yes | No |

| 4 Maccabees | No | No | No | No | No (appendix) | No (appendix) | Yes | No (early tradition) | No (?) – inc. in some mss. | No (Coptic ms.) | No | No (?) – inc. in some mss. | No |

| Jubilees | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Enoch | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| 1 Ethiopian Maccabees | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| 2 and 3 Ethiopian Maccabees[O 13] | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Ethiopic Pseudo-Josephus (Zëna Ayhud) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon)[O 14] | No | No |

| Josephus' Jewish War VI | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No – inc. in some mss.[O 15] | No | No | No – inc. in some mss.[O 15] | No |

| Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs | No | No | No | No | No (Greek ms.) | No | No | No – inc. in some mss. | No | No | No | No | No |

| Joseph and Asenath | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No – inc. in some mss. | No | No | No (early tradition?)[O 16] | No | No |

| Wisdom | Ketuvim | ||||||||||||

| Book of Job | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Iyov |

| Psalms 1–150[O 17] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Tehillim |

| Psalm 151 | No | No | No | No – inc. in some mss. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Psalms 152–155 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (?) | No | No | No (?) – inc. in some mss. | No |

| Psalms of Solomon[O 18] | No | No | No | No | No – inc. in some mss. | No | No | No | No – inc. in some mss. | No | No | No – inc. in some mss. | No |

| Proverbs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (in 2 books) | Yes | Yes Mishlei |

| Ecclesiastes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Qohelet |

| Song of Songs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Canticle of Canticles | Yes Aisma Aismaton | Yes Aisma Aismaton | Yes Aisma Aismaton | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Shir Hashirim |

| Book of Wisdom or Wisdom of Solomon | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Wisdom of Sirach or Sirach (1–51)[O 19] | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes[O 20] Ecclesiasticus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Prayer of Solomon (Sirach 52)[O 21] | No | No | No | No (?) – inc. in some mss. | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Major prophets | Nevi'im | ||||||||||||

| Isaiah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Isaias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Yeshayahu |

| Ascension of Isaiah | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No – liturgical (?)[O 22] | No | No | No – Ethiopic mss. (early tradition?)[O 23] | No | No |

| Jeremiah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Jeremias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Yirmeyahu |

| Lamentations (1–5) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[O 24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (part of Säqoqawä Eremyas)[O 25] | No | Yes Eikhah (part of Ketuvim) |

| Ethiopic Lamentations (6; 7:1–11,63) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (part of Säqoqawä Eremyas)[O 25] | No | No |

| Baruch | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[O 26][O 27] | Yes | No |

| Letter of Jeremiah | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes (chapter 6 of Baruch) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (part of Säqoqawä Eremyas)[O 28][O 25][O 27] | Yes | No |

| Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch (2 Baruch 1–77)[O 29] | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (?) | No | No | No (?) – inc. in some mss. | No |

| Letter of Baruch (2 Baruch 78–87)[O 29] | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (?) | No | No | Yes (?) | No |

| Greek Apocalypse of Baruch (3 Baruch)[O 30] | No | No | No | No | No (Greek ms.) | No (Slavonic ms.) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 4 Baruch | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (part of Säqoqawä Eremyas) | No | No |

| Ezekiel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Ezechiel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Yekhezqel |

| Daniel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Daniyyel (part of Ketuvim) |

| Additions to Daniel[O 31] | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Twelve Minor Prophets | Trei Asar | ||||||||||||

| Hosea | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Osee | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Joel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Amos | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obadiah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Abdias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jonah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Jonas | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Micah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Micheas | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nahum | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Habakkuk | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Habacuc | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zephaniah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Sophonias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Haggai | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Aggeus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zechariah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Zacharias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Malachi | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Malachias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table notes

The table uses the spellings and names present in modern editions of the Bible, such as the New American Bible Revised Edition, Revised Standard Version and English Standard Version. The spelling and names in both the 1609–1610 Douay Old Testament (and in the 1582 Rheims New Testament) and the 1749 revision by Bishop Challoner (the edition currently in print used by many Catholics, and the source of traditional Catholic spellings in English) and in the Septuagint differ from those spellings and names used in modern editions that derive from the Hebrew Masoretic text.[64]

The King James Version references some of these books by the traditional spelling when referring to them in the New Testament, such as "Esaias" (for Isaiah). In the spirit of ecumenism more recent Catholic translations (e.g., the New American Bible, Jerusalem Bible, and ecumenical translations used by Catholics, such as the Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition) use the same "standardized" (King James Version) spellings and names as Protestant Bibles (e.g., 1 Chronicles, as opposed to the Douaic 1 Paralipomenon, 1–2 Samuel and 1–2 Kings, instead of 1–4 Kings) in the protocanonicals.

The Talmud in Bava Batra 14b gives a different order for the books in Nevi'im and Ketuvim. This order is also quoted in Mishneh Torah Hilchot Sefer Torah 7:15. The order of the books of the Torah are universal through all denominations of Judaism and Christianity.

- The term "Protestant" is not accepted by all Christian denominations who often fall under this title by default—especially those who view themselves as a direct extension of the New Testament church. However, the term is used loosely here to include most of the non-Roman Catholic Protestant, Charismatic/Pentecostal, Reformed, and Evangelical churches. Other western churches and movements that have a divergent history from Roman Catholicism, but are not necessarily considered to be historically Protestant, may also fall under this umbrella terminology.

- The Roman Catholic Canon as represented in this table reflects the Latin tradition. Some Eastern Rite churches who are in fellowship with the Roman Catholic Church may have different books in their canons.

- The growth and development of the Armenian Biblical canon is complex. Extra-canonical Old Testament books appear in historical canon lists and recensions that are either exclusive to this tradition, or where they do exist elsewhere, never achieved the same status. These include the Deaths of the Prophets, an ancient account of the lives of the Old Testament prophets, which is not listed in this table. (It is also known as the Lives of the Prophets.) Another writing not listed in this table entitled the Words of Sirach—which is distinct from Ecclesiasticus and its prologue—appears in the appendix of the 1805 Armenian Zohrab Bible alongside other, more commonly known works.

- Adding to the complexity of the Orthodox Tewahedo Biblical canon, the national epic Kebra Negast has an elevated status among many Ethiopian Christians to such an extent that some consider it to be inspired scripture.

- The English Apocrypha includes the Prayer of Manasseh, 1 & 2 Esdras, the Additions to Esther, Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, the Book of Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, the Letter of Jeremiah, and the Additions to Daniel. The Lutheran Apocrypha omits from this list 1 & 2 Esdras. Some Protestant Bibles include 3 Maccabees as part of the Apocrypha. However, many churches within Protestantism—as it is presented here—reject the Apocrypha, do not consider it useful, and do not include it in their Bibles.

- The Prayer of Manasseh is included as part of the Book of Odes, which follows the Psalms in Eastern Orthodox Bibles. The rest of the Book of Odes consists of passages found elsewhere in the Bible.

- 2 Ezra, 3 Ezra, and 3 Maccabees are included in Bibles and have an elevated status within the Armenian scriptural tradition, but are considered "extra-canonical".

- In many eastern Bibles, the Apocalypse of Ezra is not an exact match to the longer Latin Esdras–2 Esdras in KJV or 4 Esdras in the Vulgate—which includes a Latin prologue (5 Ezra) and epilogue (6 Ezra). However, a degree of uncertainty continues to exist here, and it is certainly possible that the full text—including the prologue and epilogue—appears in Bibles and Biblical manuscripts used by some of these eastern traditions. Also of note is the fact that many Latin versions are missing verses 7:36–7:106. (A more complete explanation of the various divisions of books associated with the scribe Ezra may be found in the Wikipedia article entitled "Esdras".)

- Evidence strongly suggests that a Greek manuscript of 4 Ezra once existed; this furthermore implies a Hebrew origin for the text.

- An early fragment of 6 Ezra is known to exist in the Greek language, implying a possible Hebrew origin for 2 Esdras 15–16.

- Esther's placement within the canon was questioned by Luther. Others, like Melito, omitted it from the canon altogether.

- The Latin Vulgate, Douay-Rheims, and Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition place First and Second Maccabees after Malachi; other Catholic translations place them after Esther.

- 2 and 3 Meqabyan, though relatively unrelated in content, are often counted as a single book.

- Some sources place Zëna Ayhud within the "narrower canon".

- A Syriac version of Josephus's Jewish War VI appears in some Peshitta manuscripts as the "Fifth Book of Maccabees", which is clearly a misnomer.

- Several varying historical canon lists exist for the Orthodox Tewahedo tradition. In one particular list Archived 10 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine found in a British Museum manuscript (Add. 16188), a book of Assenath is placed within the canon. This most likely refers to the book more commonly known as Joseph and Asenath. An unknown book of Uzziah is also listed there, which may be connected to the lost Acts of Uziah referenced in 2 Chronicles 26:22.

- Some traditions use an alternative set of liturgical or metrical Psalms.

- In many ancient manuscripts, a distinct collection known as the Odes of Solomon is found together with the similar Psalms of Solomon.

- The book of Sirach is usually preceded by a non-canonical prologue written by the author's grandson.

- In some Latin versions, chapter 51 of Ecclesiasticus appears separately as the "Prayer of Joshua, son of Sirach".

- A shorter variant of the prayer by King Solomon in 1 Kings 8:22–52 appeared in some medieval Latin manuscripts and is found in some Latin Bibles at the end of or immediately following Ecclesiasticus. The two versions of the prayer in Latin may be viewed online for comparison at the following website: BibleGateway.com: Sirach 52 / 1 Kings 8:22–52; Vulgate

- The "Martyrdom of Isaiah" is prescribed reading to honor the prophet Isaiah within the Armenian Apostolic liturgy (see this list). While this likely refers to the account of Isaiah's death within the Lives of the Prophets, it may be a reference to the account of his death found within the first five chapters of the Ascension of Isaiah, which is widely known by this name. The two narratives have similarities and may share a common source.

- The Ascension of Isaiah has long been known to be a part of the Orthodox Tewahedo scriptural tradition. Though it is not currently considered canonical, various sources attest to the early canonicity—or at least "semi-canonicity"—of this book.

- In some Latin versions, chapter 5 of Lamentations appears separately as the "Prayer of Jeremiah".

- Ethiopic Lamentations consists of eleven chapters, parts of which are considered to be non-canonical.

- The canonical Ethiopic version of Baruch has five chapters, but is shorter than the LXX text.

- Some Ethiopic translations of Baruch may include the traditional Letter of Jeremiah as the sixth chapter.

- The "Letter to the Captives" found within Säqoqawä Eremyas—and also known as the sixth chapter of Ethiopic Lamentations—may contain different content from the Letter of Jeremiah (to those same captives) found in other traditions.

- The Letter of Baruch is found in chapters 78–87 of 2 Baruch—the final ten chapters of the book. The letter had a wider circulation and often appeared separately from the first 77 chapters of the book, which is an apocalypse.

- Included here for the purpose of disambiguation, 3 Baruch is widely rejected as a pseudepigraphon and is not part of any Biblical tradition. Two manuscripts exist—a longer Greek manuscript with Christian interpolations and a shorter Slavonic version. There is some uncertainty about which was written first.

- Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, and The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children.

New Testament

Among the various Christian denominations, the New Testament canon is a generally agreed-upon list of 27 books. However, the way in which those books are arranged may vary from tradition to tradition. For instance, in the Slavonic, Orthodox Tewahedo, Syriac, and Armenian traditions, the New Testament is ordered differently from what is considered to be the standard arrangement. Protestant Bibles in Russia and Ethiopia usually follow the local Orthodox order for the New Testament. The Syriac Orthodox Church and the Assyrian Church of the East both adhere to the Peshitta liturgical tradition, which historically excludes five books of the New Testament Antilegomena: 2 John, 3 John, 2 Peter, Jude, and Revelation. However, those books are included in certain Bibles of the modern Syriac traditions.

Other New Testament works that are generally considered apocryphal nonetheless appear in some Bibles and manuscripts. For instance, the Epistle to the Laodiceans[note 5] was included in numerous Latin Vulgate manuscripts, in the eighteen German Bibles prior to Luther's translation, and also a number of early English Bibles, such as Gundulf's Bible and John Wycliffe's English translation—even as recently as 1728, William Whiston considered this epistle to be genuinely Pauline. Likewise, the Third Epistle to the Corinthians[note 6] was once considered to be part of the Armenian Orthodox Bible,[65] but is no longer printed in modern editions. Within the Syriac Orthodox tradition, the Third Epistle to the Corinthians also has a history of significance. Both Aphrahat and Ephraem of Syria held it in high regard and treated it as if it were canonical.[66] However, it was left-out of the Peshitta and ultimately excluded from the canon altogether.

The Didache,[note 7] The Shepherd of Hermas,[note 8] and other writings attributed to the Apostolic Fathers, were once considered scriptural by various early Church fathers. They are still being honored in some traditions, though they are no longer considered to be canonical. However, certain canonical books within the Orthodox Tewahedo traditions find their origin in the writings of the Apostolic Fathers as well as the Ancient Church Orders. The Orthodox Tewahedo churches recognize these eight additional New Testament books in its broader canon. They are as follows: the four books of Sinodos, the two books of the Covenant, Ethiopic Clement, and the Ethiopic Didascalia.[67]

Table

| Books | Protestant tradition | Roman Catholic tradition | Eastern Orthodox tradition | Armenian Apostolic tradition[N 1] | Coptic Orthodox tradition | Orthodox Tewahedo traditions | Syriac Christian traditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical gospels[N 2] | |||||||

| Matthew | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 3] |

| Mark[N 4] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 3] |

| Luke | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 3] |

| John[N 4][N 5] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 3] |

| Apostolic history | |||||||

| Acts[N 4] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Acts of Paul and Thecla[N 6][68][69] | No | No | No | No (early tradition) | No | No | No (early tradition) |

| Pauline epistles | |||||||

| Romans | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 1 Corinthians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Corinthians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Corinthians to Paul and 3 Corinthians[N 6][N 7] | No | No | No | No − inc. in some mss. | No | No | No (early tradition) |

| Galatians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ephesians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Philippians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Colossians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Laodiceans | No − inc. in some eds.[N 8] | No − inc. in some mss. | No | No | No | No | No |

| 1 Thessalonians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Thessalonians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 1 Timothy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Timothy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Titus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Philemon | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| General epistles | |||||||

| Hebrews | Yes[N 9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| James | Yes[N 9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 1 Peter | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Peter | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 10] |

| 1 John[N 4] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 John | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 10] |

| 3 John | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 10] |

| Jude | Yes[N 9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 10] |

| Apocalypse[N 11] | |||||||

| Revelation | Yes[N 9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 10] |

| Apostolic Fathers[N 12] and Church Orders[N 13] | |||||||

| 1 Clement[N 14] | No (Codices Alexandrinus and Hierosolymitanus) | ||||||

| 2 Clement[N 14] | No (Codices Alexandrinus and Hierosolymitanus) | ||||||

| Shepherd of Hermas[N 14] | No (Codex Siniaticus) | ||||||

| Epistle of Barnabas[N 14] | No (Codices Hierosolymitanus and Siniaticus) | ||||||

| Didache[N 14] | No (Codex Hierosolymitanus) | ||||||

| Ser'atä Seyon (Sinodos) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Te'ezaz (Sinodos) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Gessew (Sinodos) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Abtelis (Sinodos) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Book of the Covenant 1 (Mäshafä Kidan) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Book of the Covenant 2 (Mäshafä Kidan) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Ethiopic Clement (Qälëmentos)[N 15] | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Ethiopic Didescalia (Didesqelya)[N 15] | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

Table notes

- The growth and development of the Armenian Biblical canon is complex. Extra-canonical New Testament books appear in historical canon lists and recensions that are either distinct to this tradition, or where they do exist elsewhere, never achieved the same status. Some of the books are not listed in this table. These include the Prayer of Euthalius, the Repose of St. John the Evangelist, the Doctrine of Addai (some sources replace this with the Acts of Thaddeus), a reading from the Gospel of James (some sources replace this with the Apocryphon of James), the Second Apostolic Canons, the Words of Justus, Dionysius Aeropagite, the Acts of Peter (some sources replace this with the Preaching of Peter), and a Poem by Ghazar. (Various sources also mention undefined Armenian canonical additions to the Gospels of Mark and John, however, these may refer to the general additions—Mark 16:9–20 and John 7:53–8:11—discussed elsewhere in these notes.) A possible exception here to canonical exclusivity is the Second Apostolic Canons, which share a common source—the Apostolic Constitutions—with certain parts of the Orthodox Tewahedo New Testament broader canon. The correspondence between King Agbar and Jesus Christ, which is found in various forms—including within both the Doctrine of Addai and the Acts of Thaddeus—sometimes appears separately (see this list). It is noteworthy that the Prayer of Euthalius and the Repose of St. John the Evangelist appear in the appendix of the 1805 Armenian Zohrab Bible. However, some of the aforementioned books, though they are found within canon lists, have nonetheless never been discovered to be part of any Armenian Biblical manuscript.

- Though widely regarded as non-canonical, the Gospel of James obtained early liturgical acceptance among some Eastern churches and remains a major source for many of Christendom's traditions related to Mary, the mother of Jesus.

- The Diatessaron, Tatian's gospel harmony, became a standard text in some Syriac-speaking churches down to the 5th century, when it gave-way to the four separate gospels found in the Peshitta.

- Parts of these four books are not found in the most reliable ancient sources; in some cases, are thought to be later additions; and have therefore not historically existed in every Biblical tradition. They are as follows: Mark 16:9–20, John 7:53–8:11, the Comma Johanneum, and portions of the Western version of Acts. To varying degrees, arguments for the authenticity of these passages—especially for the one from the Gospel of John—have occasionally been made.

- Skeireins, a commentary on the Gospel of John in the Gothic language, was included in the Wulfila Bible. It exists today only in fragments.

- The Acts of Paul and Thecla, the Epistle of the Corinthians to Paul, and the Third Epistle to the Corinthians are all portions of the greater Acts of Paul narrative, which is part of a stichometric catalogue of New Testament canon found in the Codex Claromontanus, but has survived only in fragments. Some of the content within these individual sections may have developed separately, however.

- The Third Epistle to the Corinthians often appears with and is framed as a response to the Epistle of the Corinthians to Paul.

- The Epistle to the Laodiceans is present in some western non-Roman Catholic translations and traditions. Especially of note is John Wycliffe's inclusion of the epistle in his English translation, and the Quakers' use of it to the point where they produced a translation and made pleas for its canonicity (Poole's Annotations, on Col. 4:16). The epistle is nonetheless widely rejected by the vast majority of Protestants.

- These four works were questioned or "spoken against" by Martin Luther, and he changed the order of his New Testament to reflect this, but he did not leave them out, nor has any Lutheran body since. Traditional German Luther Bibles are still printed with the New Testament in this changed "Lutheran" order. The vast majority of Protestants embrace these four works as fully canonical.

- The Peshitta excludes 2 John, 3 John, 2 Peter, Jude, and Revelation, but certain Bibles of the modern Syriac traditions include later translations of those books. Still today, the official lectionary followed by the Syriac Orthodox Church and the Assyrian Church of the East, present lessons from only the twenty-two books of Peshitta, the version to which appeal is made for the settlement of doctrinal questions.

- The Apocalypse of Peter, though not listed in this table, is mentioned in the Muratorian fragment and is part of a stichometric catalogue of New Testament canon found in the Codex Claromontanus. It was also held in high regard by Clement of Alexandria.

- Other known writings of the Apostolic Fathers not listed in this table are as follows: the seven Epistles of Ignatius, the Epistle of Polycarp, the Martyrdom of Polycarp, the Epistle to Diognetus, the fragment of Quadratus of Athens, the fragments of Papias of Hierapolis, the Reliques of the Elders Preserved in Irenaeus, and the Apostles' Creed.

- Though they are not listed in this table, the Apostolic Constitutions were considered canonical by some including Alexius Aristenus, John of Salisbury, and to a lesser extent, Grigor Tat'evatsi. They are even classified as part of the New Testament canon within the body of the Constitutions itself. Moreover, they are the source for a great deal of the content in the Orthodox Tewahedo broader canon.

- These five writings attributed to the Apostolic Fathers are not currently considered canonical in any Biblical tradition, though they are more highly regarded by some more than others. Nonetheless, their early authorship and inclusion in ancient Biblical codices, as well as their acceptance to varying degrees by various early authorities, requires them to be treated as foundational literature for Christianity as a whole.

- Ethiopic Clement and the Ethiopic Didascalia are distinct from and should not be confused with other ecclesiastical documents known in the west by similar names.

Latter Day Saint canons

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The standard works of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) consists of several books that constitute its open scriptural canon, and include the following:

- The King James Version of the Bible[note 9] – without the Apocrypha

- The Book of Mormon: Another Testament of Jesus Christ

- The Doctrine and Covenants of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- The Pearl of Great Price

The Pearl of Great Price contains five sections: "Selections from the Book of Moses", "The Book of Abraham", "Joseph Smith–Matthew", "Joseph Smith–History" and "The Articles of Faith". The Book of Moses and Joseph Smith–Matthew are portions of the Book of Genesis and the Gospel of Matthew (respectively) from the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible. (The Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible is also known as the Inspired Version of the Bible.)

The manuscripts of the unfinished Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible (JST) state that "the Song of Solomon is not inspired scripture."[70] However, it is still printed in every version of the King James Bible published by the church.

The Standard Works are printed and distributed by the LDS church in a single binding called a "Quadruple Combination" or a set of two books, with the Bible in one binding, and the other three books in a second binding called a "Triple Combination". Current editions of the Standard Works include a bible dictionary, photographs, maps and gazetteer, topical guide, index, footnotes, cross references, excerpts from the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible and other study aids.

Other Latter Day Saint sects

Canons of various Latter Day Saint denominations diverge from the LDS Standard Works. Some accept only portions of the Standard Works. For instance, the Bickertonite sect does not consider the Pearl of Great Price or Doctrines and Covenants to be scriptural. Rather, they believe that the New Testament scriptures contain a true description of the church as established by Jesus Christ, and that both the King James Bible and Book of Mormon are the inspired word of God.[71] Some denominations accept earlier versions of the Standard Works or work to develop corrected translations. Others have purportedly received additional revelation.

The Community of Christ points to Jesus Christ as the living Word of God,[72] and it affirms the Bible, along with the Book of Mormon, as well as its own regularly appended version of Doctrines and Covenants as scripture for the church. While it publishes a version of the Joseph Smith Translation—which includes material from the Book of Moses—the Community of Christ also accepts the use of other translations of the Bible, such as the standard King James Version and the New Revised Standard Version.

Like the aforementioned Bickertonites, the Church of Christ (Temple Lot) rejects the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price, as well as the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible, preferring to use only the King James Bible and the Book of Mormon as doctrinal standards. The Book of Commandments is accepted as being superior to the Doctrine and Covenants as a compendium of Joseph Smith's early revelations, but is not accorded the same status as the Bible or Book of Mormon.

The Word of the Lord and The Word of the Lord Brought to Mankind by an Angel are two related books considered to be scriptural by certain (Fettingite) factions that separated from the Temple Lot church. Both books contain revelations allegedly given to former Church of Christ (Temple Lot) Apostle Otto Fetting by an angelic being who claimed to be John the Baptist. The latter title (120 messages) contains the entirety of the former's material (30 msgs.) with additional revelations (90 msgs.) purportedly given to William A. Draves by this same being, after Fetting's death. Neither are accepted by the larger Temple Lot body of believers.[73]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite) considers the Bible (when correctly translated), the Book of Mormon, and editions of the Doctrine and Covenants published prior to Joseph Smith's death (which contained the Lectures on Faith) to be inspired scripture. They also hold the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible to be inspired, but do not believe modern publications of the text are accurate. Other portions of The Pearl of Great Price, however, are not considered to be scriptural—though are not necessarily fully rejected either. The Book of Jasher was consistently used by both Joseph Smith and James Strang, but as with other Latter Day Saint denominations and sects, there is no official stance on its authenticity, and it is not considered canonical.[74]

An additional work called The Book of the Law of the Lord is also accepted as inspired scripture by the Strangites. They likewise hold as scriptural several prophecies, visions, revelations, and translations printed by James Strang, and published in the Revelations of James J. Strang. Among other things, this text contains his purported "Letter of Appointment" from Joseph Smith and his translation of the Voree plates.

The Church of Jesus Christ (Cutlerite) accepts the following as scripture: the Inspired Version of the Bible (including the Book of Moses and Joseph Smith–Matthew), the Book of Mormon, and the 1844 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants (including the Lectures on Faith). However, the revelation on tithing (section 107 in the 1844 edition; 119 in modern LDS editions) is emphatically rejected by members of this church, as it is not believed to be given by Joseph Smith. The Book of Abraham is rejected as scripture, as are the other portions of the Pearl of Great Price that do not appear in the Inspired Version of the Bible.

Many Latter Day Saint denominations have also either adopted the Articles of Faith or at least view them as a statement of basic theology. (They are considered scriptural by the larger LDS church and are included in The Pearl of Great Price.) At times, the Articles have been adapted to fit the respective belief systems of various faith communities.

Islamic canon

| Quran |

|---|

|

|

While Islam does not use the Bible, it does have a canon of scripture in the Quran, the holy book of Islam. Muslims believe the word of God was revealed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and in collections of hadith, the record of what Muslims believe to be the words, actions, and the silent approval of Muhammad.

Quran

Uthman and the canonization of the Quran

The Quran was canonized after Muhammad's death in 632 CE. According to traditional Islamic history, the third caliph, Uthman (r. 23/644–35 AH/655 CE) established the canonical Quran, reportedly starting the process in 644 CE,[75] and completing the work around 650 CE (the exact date was not recorded by early Arab annalists).[76] It is generally accepted that the Uthmanic text comprises all 114 surahs (chapters of the Quran) in the order known today.[77]

The Quranic canon is the form of the Quran as recited and written in which it is religiously binding for the Muslim community. This canonical corpus is closed and fixed in the sense that nothing in the Quran can be changed or modified.[77]

According to the traditional Islamic narrative, by the time of Uthman's caliphate, there was a perceived need for clarification of Quran reading. The holy book had often been spread to others orally by Muslims who had memorized the Quran in its entirety (huffaz), but now "sharp divergence" had appeared in recitation of the book among Muslims.[76] It is believed the general Hudhayfah ibn al-Yaman reported this problem to the caliph and asked him to establish a unified text. According to the history of al-Tabari, during the expedition to conquer Armenia and Azerbaijan there were 10,000 Kufan Muslim warriors, 6,000 in Azerbaijan and 4,000 at Rayy,[78] and a large number of these soldiers disagreed about the correct way of reciting the Quran.[79]

What was more, many of the huffaz were dying. Seventy had been killed in the Battle of Yamama.[80] The Islamic empire had also grown considerably, expanding into Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and Iran, bringing into Islam's fold many new converts from various cultures with varying degrees of isolation.[81] These converts spoke a variety of languages but were not well learned in Arabic, and so Uthman felt it was important to standardize the written text of the Quran on one specific Arabic dialect.

Uthman obtained written "sheets" or parts of the Quran from Ḥafṣa, one of the widows of Muhammad. Other parts collected from Companions had been "written down on parchment, stone, palm leaves and the shoulder blades of camels".[82] He appointed a commission consisting of a scribe of Muhammad, Zayd ibn Thabit and three prominent Meccans, and instructed them to copy the sheets into several volumes based on the dialect of the Quraysh — the tribe of Muhammad and the main tribe of Mecca.[83]

Uthman's reaction in 653 is recorded in the following hadith from Sahih al-Bukhari, 6:61:510:

So Uthman sent a message to Hafsa saying, "Send us the manuscripts of the Quran so that we may compile the Quranic materials in perfect copies and return the manuscripts to you." Hafsa sent it to Uthman. Uthman then ordered Zaid bin Thabit, Abdullah bin Az Zubair, Said bin Al-As and Abdur Rahman bin Harith bin Hisham to rewrite the manuscripts in perfect copies. Uthman said to the three Quraishi men, "In case you disagree with Zaid bin Thabit on any point in the Quran, then write it in the dialect of Quraish, the Quran was revealed in their tongue." They did so, and when they had written many copies, 'Uthman returned the original manuscripts to Hafsa. 'Uthman sent to every Muslim province one copy of what they had copied and ordered that all the other Quranic materials, whether written in fragmentary manuscripts or whole copies, be burnt. Zayd bin Thabit added, "A Verse from Surat Ahzab was missed by me when we copied the Quran and I used to hear Allah's Apostle reciting it. So we searched for it and found it with Khuzaima bin Thabit Al-Ansari. [That verse was]: 'Among the Believers are men who have been true in their covenant with Allah.'

When the task was finished Uthman kept one copy in Medina and sent others to Kufa, Baṣra, Damascus, and, according to some accounts, Mecca, and ordered that all other variant copies of the Quran be destroyed. Some non-Uthmanic Qurans are thought to have survived in Kufa, where Abdullah ibn Masud and his followers reportedly refused.[83]

This is one of the most contested issues and an area where many non-Muslim and Muslim scholars often clash.[77]

Variants

According to Islamic tradition the Quran was revealed to Muhammad in seven ahruf (translated variously as "styles",[84] "forms", or "modes",[85] singular harf). However, Uthman canonized only one of the harf (according to tradition).[86] This was because after Muhammad's death a rivalry began to develop among some of the Arab tribes over the alleged superiority of their ahruf. In addition, some new converts to Islam began mixing the various forms of recitation out of ignorance.[86][87] Consequently, when the Quran was canonized, caliph Uthman ordered the rest of the ahruf to be destroyed.

This does not mean that only one "reading" of the Quran is canonized. The single harf canonized by Uthman did not include vowels or diacritical marks for some consonants, which allowed for variant readings. Seven readings, known as Qira'at, were noted by scholar Abu Bakr Ibn Mujāhid and canonized in the 8th century CE.[88] Later scholars, such as Ibn al-Jazari, added three other reciters (Abu Ja’far from Madinah, Ya’qub from Basrah, and Khalaf from Kufa) to form the canonical list of ten Qira'at.[89][90]

Of the ten, the one qira'at has become so popular that (according to one source) "for all practical purposes", it is the one Quranic version in general use in the Muslim world today[91][note 10] -- Hafs ‘an ‘Asim, specifically the standard Egyptian edition of the Quran first published on July 10, 1924 in Cairo. Mass-produced printing press mus'haf (written copies of the Quran) have been credited with narrowing the diversity of qira'at.[94]

Shia belief

While Shia (who make up about 10-15% of the Muslim population) use the same Quran as Sunni Muslims, they have a different story of its canonization, connected to the initial rift between the two groups, i.e. that the Companions of the Prophet (allegedly) unjustly denied Ali this leadership position. Most Shī‘ah believe the Quran was gathered and compiled not by Uthman[95] (one of The Companions) but by Muhammad himself during his lifetime.[96][97][98]

According to the Shia website Al-Islam, a minority of Shia believe the Quran was compiled by Ali, "after the Prophet’s death but before people finally accepted him as a caliph".[99] (Another small minority of Shia Muslims disputed the canonical validity of the Uthmanic codex,[100] reportedly only seven Shia scholars contended there were omissions in the Uthmanic codex.)[101]

According to influential Shia marja' Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei, Uthman's collection of the Quran was metaphorical, not physical. Rather than collecting the verses and surahs in one volume (Al-Khoei argues), Uthman united Muslims on the reading of one authoritative recension — the one in circulation among most Muslims, having reached them through uninterrupted transmission from Muhammad.[102]

However, the story of the canonization of the Quran is of importance in Islam for a number of reasons. Since at least the 10th century anti-Shia Sunni Muslims have accused Shia of claiming that the contemporary Quran differs from what was revealed to Muhammad; of believing that the original Quran was edited to remove any references to (among other things) the rights of Ali and the Imams (descendants of Ali that should be accepted as leaders and guides of the Muslim community).[103] The idea that the Quran was distorted is regard by these Sunnis as an outrageous Shia "heresy".[104]

Twelver Shia (who make up the overwhelming majority of Shia) did at one time believe in the distortion of the Quran, according to western Islamic scholar Etan Kohlberg — and the belief was common among Shia during the early Islamic centuries,[105] but waned during the era of the Buyid dynasty (934–1062).[106] Kohlberg claims that Ibn Babawayh was the first major Twelver author "to adopt a position identical to that of the Sunnis".[107] This change in belief was primarily a result of the Shia "rise to power at the centre of the Sunni 'Abbasid caliphate," whence belief in the corruption of the Quran became untenable vis-a-vis the position of Sunni “orthodoxy”.[108]

The Brill Encyclopedia of the Quran also states some Shia Muslims have disputed the canonical validity of the Uthmanic codex,[109] And according to Hossein Modarressi, seven early Shia scholars believed there are omissions in the Uthmanic codex.[101]

Hadith

Second only to the Quran in authority as a source for religious law and moral guidance in Islam,[110] are Hadith—the record of what Muslims believe to be the words, actions, and the silent approval of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. While the number of verses pertaining to law in the Quran is relatively few, hadith give direction on everything from details of religious obligations (such as Ghusl or Wudu, ablutions[111] for salat prayer), to the correct forms of salutations[112] and the importance of benevolence to slaves.[113] Thus the "great bulk" of the rules of Sharia (Islamic law) are derived from hadith, rather than the Quran.)[114] Scriptural authority for hadith comes from the Quran which enjoins Muslims to emulate Muhammad and obey his judgments (in verses such as 24:54, 33:21).

Because there were a large number of false hadith, a great deal of effort was expended by scholars in a field known as hadith studies to sift through and grade hadith on a scale of authenticity. In Sunni Islam there are six major authentic hadith collections known as the Kutub al-Sittah (six books)[115] or al-Sihah al-Sittah (the authentic six). The two "most famous" 'Authentic' (Sahih) ḥadīth collections are those of Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim — known as the sahihayn (or two sahih). These works came out over two centuries after the Uthmanic codex, (the hadith collections do not have original publishing dates but the authors' death dates range from 870 to 915 CE).

Because the Kutub al-Sittah hadith collections used by Sunni Muslims were based on narrators and transmitters that Shia Islam believed treated Ali unfairly and so were not trustworthy, Shia follow different hadith collections. The most famous being "The Four Books", which were compiled by three authors who are known as the 'Three Muhammads'.[116] The Four Books are: Kitab al-Kafi by Muhammad ibn Ya'qub al-Kulayni al-Razi (329 AH), Man la yahduruhu al-Faqih by Muhammad ibn Babuya and Al-Tahdhib and Al-Istibsar both by Shaykh Muhammad Tusi. Shi'a clerics also make use of extensive collections and commentaries by later authors.

Not only were the hadith collections compiled centuries after the Quran, but their canonization also came much later. Scholar Jonathan A. C. Brown has studied the process of canonization of the two "most famous" collections of hadith -- sahihayn of al-Bukhari and Muslim -- which went from "controversial to indispensable" over the centuries.[117]

From their very creation, they were subject to withering criticism and rejection: Muslim was forced to argue that his book was merely meant as a 'private collection' (94) and al-Bukhari was acused of plagiarism (95). The 4th/10th and 5th/11th centuries were no kinder, for while the Shafi'is [school of fiqh law] championed the Sahihayn, Malikis were initially enamored of their own texts and 'tangential to the Sahihayn network" (37), while the Hanbalis were openly critical. Not until the mid-5th/11th century did these schools come to a tacit agreement on the status of 'the Sahihayn canon as a measure of authenticity in polemics and exposition of their schools' doctrines' (222); it would be three more centuries before the Hanafis would join them in this assessment.[note 11][118]

Brown writes that the books achieved iconic status in the Sunni Muslim community such that public readings of them were made in Cairo in 790 AH/1388 CE to ward off plague and the Moroccan statesman Mawlay Isma'il (d.1727) "dubbed his special troops the 'slaves of al-Bukhari'".[119]

See also

- Authorship of the Bible

- Bible

- Bible citation

- Bible translations

- Biblical apocrypha

- Biblical criticism

- Biblical manuscript

- Canon (fiction) – a concept inspired by Biblical canon

- Canonical criticism

- Jewish apocrypha

- List of Old Testament pseudepigrapha

- New Testament apocrypha

- Non-canonical books referenced in the Bible

- Pseudepigraph

Notes

- For a fuller discussion of issues regarding the canonicity of Enoch, see the Reception of Enoch in antiquity.

- Because of the lack of solid information on this subject, the exclusion of Lamentations from the Ethiopian Jewish canon is not a certainty. Furthermore, some uncertainty remains concerning the exclusion of various smaller deuterocanonical writings from this canon including the Prayer of Manasseh, the traditional additions to Esther, the traditional additions to Daniel, Psalm 151, and portions of Säqoqawä Eremyas.

- Josephus's The Jewish War and Antiquities of the Jews are highly regarded by Christians because they provide valuable insight into 1st century Judaism and early Christianity. Moreover, in Antiquities, Josephus made two extra-Biblical references to Jesus, which have played a crucial role in establishing him as a historical figure.