Immigration to Denmark

Denmark has seen a steady increase in immigration over the past 30 years, with the majority of new immigrants originating from non-Western countries. As of 2014, more than 8 percent of the population of Denmark consists of immigrants. The population of immigrants is approximately 476,059, excluding Danish born descendants of immigrants to Denmark. This recent shift in demographics has posed challenges to the nation as it attempts to address religious and cultural difference, employment gaps, education of both immigrants and their descendants, spatial segregation, crime rates and language abilities.

History

Prior to World War I, Denmark experienced a mass emigration to non-European nations.[1] During World War I, the Interbellum and World War II, migration to and from Denmark halted. Immigration to Denmark increased rapidly during the 1960s as the manufacturing economy expanded and the demand for labor increased.[2] As a result of the increased demand, a majority of immigrants that came to Denmark during the 1960s and early 1970s were migrant laborers with guest worker status. A large proportion of the guest worker population came from Turkey, Yugoslavia, and Pakistan.[3]

At the end of the 1960s immigration policy became more stringent, greatly reducing the number of immigrants arriving in Denmark.[2] Immigration was limited further in the early 1970s in response to the first oil crises and the resulting consequences for the Danish economy.[4] In 1972 and 1973, Denmark's immigration policy only allowed for migration of workers from within the Nordic region. After 1973 this policy was expanded to also permit labor migration from Europe.[2] Despite these limitations on immigration, the 1972 policy granted guest workers residing in Denmark the option of applying for family reunification which then became the primary method of immigration from non-European countries to Denmark.[3]

Contemporary immigration

The granting of political asylum in conjunction with the Geneva Conventions greatly impacted immigration to Denmark from the 1980s onward.[3] Although immigrants arriving as a result of family reunification continued to comprise a large portion of new immigrant populations, the number of refugees increased exponentially. In the 1990s, refugees made up a majority of inflow of immigrants.[1] The Enlargement of the European Union in 2004 led to a second wave of labor immigration since its halt in the 1970s as Central and Eastern European countries gained access to the opportunity of free movement that EU membership guarantees.[5]

According to a 2012 report published by the Danish Immigration Service, the most common reasons for receiving a Danish residence permit were:

- 54% Immigrating under the European Union and European Economic Area rules of free movement

- 19% International students

- 8% Labor Migrants with work permits

- 6% Family reunification

- 5% Asylum seekers.[6]

In 2016, an interview with Queen Margrethe II of Denmark in the book De dybeste rødder (English: The Deepest Roots) she showed, according to historians at Saxo institutet, a change in attitude to immigration towards a more restrictive stance. She stated that the Danish people should have more explicitly clarified the rules and values of Danish culture in order to be able to teach them to new arrivals. Further stated that the Danes in general have underestimated the difficulties involved in successful integration of immigrants, exemplified with the rules of a democracy not being clarified to Muslim immigrants and a lack of readiness to enforce those rules. This was received as a change in line with the attitude of the Danish people.[7][8]

In the 2010s, Denmark tightened its laws for immigration. The hold period for a family reunification was extended from one year to three, social welfare for asylum seekers has been reduced, the duration of temporary residence permits have been decreased and efforts to deport rejected asylum claimants have intensified.[9]

By 2017 the character of immigration had changed from 20 years earlier. Whereas in 1997 individuals with asylum claims and family reunification with non-Nordic citizenship constituted about half the immigrants, in 2017 the majority (65%) was composed of international students and labour migrants whereas family reunification accounted for 13% of immigrants.[10]

In November 2018, the government announced plans to house failed asylum claimants, criminal foreigners who could not be deported and foreign fighters in the Islamic State on Lindholm (Stege Bugt), an island with no permanent residents.[9][11] The scheme was approved by Danish parliament 19 December 2018. The plan was opposed by council leaders in Vordingsborg municipality and merchants in Kalvehave, where the ferry to Lindholm has its port.[12]

In December 2018, the law on Danish citizenship was changed so that a handshake was mandatory during the ceremony. The regulation would, among other things, prevent members of Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir to receive citizenship as they would never shake hands.[13]

In 2019 more people with a refugee background emigrated from Denmark than immigrated, for the first time since 2011 with a difference of 730 people according to Udlændinge- og Integrationsministeriet (UIM) figures. According to UIM, refugees from Somalia, Iraq, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Syria which left in 2019. For refugees from Eritrea, Iran and Afghanistan more arrived than departed.[14]

Identity fraud

In October 2017, the Danish Immigration Service rejected over 600 asylum applications because the applicants had lied about their identity in order to achieve preferential treatment.[15]

Child brides

Dozens of cases of girls living with older men were identified in asylum centres in Denmark in February 2016, Reuters reported in April 2016. Minister Inger Støjberg stated she planned to "stop housing child brides in asylum centres". Furthermore, a spokeswoman for the ministry indicated "There will never be exceptions in cases where one side is below the age of 15."[16]

Population demographics

Since 1980, the number of Danes has remained constant at around 5 million in Denmark and nearly all the population growth from 5.1 up to the 2018 total of 5.8 million was due to immigration.[17]

Countries of origin

The ten most represented countries of origin within the Danish immigrant population in order of greatest proportion of the population are Poland, Turkey, Germany, Iraq, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Romania, Norway, Iran, Sweden, and Pakistan.[18] According to Statistics Denmark, in the year 2014 immigrants from western countries of origin made up 41.88% of the population, whereas 58.12% of immigrants had non-western countries of origin. Statistics Denmark defines European Union member countries, Iceland, Norway, Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino, Switzerland, the Vatican State, Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand as Western Countries and all other countries as Non-Western Countries. Refugees to Denmark are primarily Iraqis, Palestinians, Bosnians, Iranians, and Somalis. The population of non-western immigrants in 2008 was more than three times the number in the 1970s when family reunification was first introduced.[19] A majority of reunified family members have been spouses and children of Danish or Nordic citizens, with only 2,000 of the 13,000 individuals reunited in 2002 coming from third world and refugee families.[20]

Immigrants from specific countries are divided into several ethnic groups. For example, there are both Russians and Chechens from Russia, Singalese and Tamil from Sri Lanka, Serbs and Albanians from Serbia. Immigrants from Iran are divided into Azeris, Kurds, Persians and Lurs.[21]

| Country | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14,086 | 29,431 | 48,773 | 59,216 | 64,172 | |

| 6,467 | 9,662 | 12,290 | 28,401 | 48,473 | |

| 213 | 625 | 2,284 | 3,707 | 42,968 | |

| 26,333 | 23,123 | 25,446 | 30,912 | 34,468 | |

| 220 | 782 | 1,934 | 6,446 | 33,591 | |

| 160 | 2,423 | 14,902 | 29,264 | 33,381 | |

| 222 | 7,938 | 19,011 | 23,775 | 27,310 | |

| 7,845 | 12,006 | 17,509 | 20,392 | 25,949 | |

| 0 | 0 | 19,727 | 22,221 | 23,203 | |

| 241 | 8,591 | 12,980 | 15,209 | 21,701 | |

| 133 | 531 | 14,856 | 16,831 | 21,072 | |

| 35 | 342 | 3,275 | 12,630 | 19,488 | |

| 13,872 | 13,116 | 14,647 | 16,067 | 17,350 | |

| 7,598 | 8,547 | 11,608 | 13,053 | 17,155 | |

| 15,979 | 13,708 | 14,604 | 15,154 | 16,620 | |

| 1,322 | 5,797 | 11,051 | 13,878 | 15,747 | |

| 1,730 | 2,194 | 3,157 | 6,382 | 15,135 | |

| 0 | 0 | 926 | 5,443 | 15,134 | |

| 872 | 1,403 | 3,610 | 9,688 | 15,038 | |

| 0 | 0 | 719 | 6,525 | 14,462 | |

| 7,452 | 10,504 | 17,176 | 16,959 | 14,383 | |

| 574 | 1,567 | 4,884 | 9,411 | 12,947 | |

| 909 | 2,023 | 3,935 | 9,307 | 12,151 | |

| 259 | 5,014 | 9,515 | 10,803 | 12,036 | |

| 2,104 | 4,267 | 7,813 | 9,831 | 11,659 | |

| 119 | 207 | 594 | 2,685 | 10,912 | |

| 5,769 | 5,357 | 6,267 | 7,458 | 9,637 | |

| 1,815 | 2,275 | 3,003 | 4,469 | 9,544 | |

| 3,155 | 3,413 | 6,011 | 8,967 | 9,308 | |

| 1,901 | 2,421 | 4,685 | 6,422 | 8,147 | |

| Total foreign population | 152,958 | 214,571 | 378,162 | 542,738 | 807,169 |

Religion

Danish law does not allow the registration of citizens based upon their religion, which makes religious demographic data of both Danish born and foreign born residents difficult to come by.[23] According to the U.S. Department of State, Islam is the second largest religion in Denmark, with Muslims comprising 4% of the population.[24] The U.S. Department of State attributes the size of this population to increased immigration to Denmark in their 2010 report, but does not elaborate on the number of Danes and foreign born populations adhering to each faith.[25] A 2007 study of religious pluralism in Denmark describes the 0.7% of the population practicing Hinduism as being primarily Tamil immigrants from Sri Lanka and Southern India.[26] The same study notes that a majority of Buddhists in Denmark are immigrants from Vietnam, Thailand, and Tibet, however the population of practicing Buddhists also includes a number of native Danes and immigrants from other Western Countries.[26]

Although religious demographics of immigrants to Denmark remain unclear, the perceived religious differences between immigrants and native Danes are a central theme in the political immigration debate.[27] Negative public attitudes toward immigration in Denmark have been linked with negative views of Islam[27] and its perceived incompatibility with Danish Protestant ethics and democratic values.[28][29] Indeed, the former Danish Prime Minister Poul Nyrup Rasmussen has been quoted,[30] urging immigrants to Denmark to "not put the Qur’an above the Constitution" following the events of 9/11 in 2001, noting a perceived disconnection between Islamic ideals and the Danish democratic state.

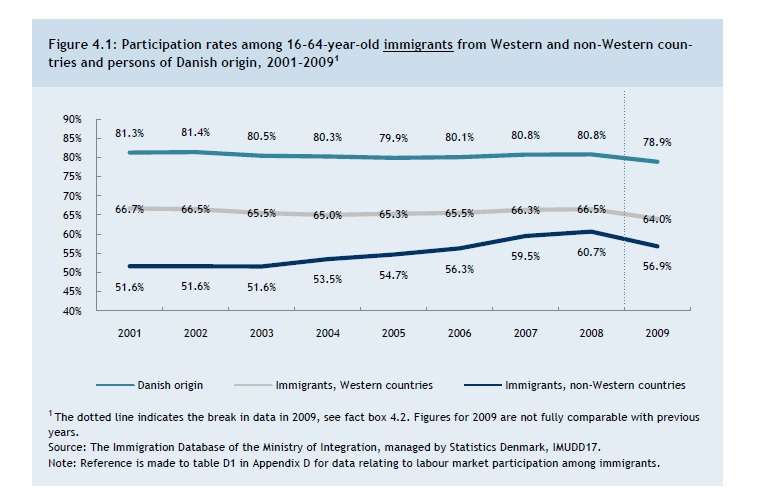

Employment

Immigrants from non-OECD countries of origin have also been found to have employment rates of 13 percentage points or more below that of immigrants from OECD countries.[31] In a 2009 report by the Ministry of Refugee, Immigration, and Integration Affairs reported that from 2001 to 2008 there was a rise from 51.6% to 60.7% labor market participation by working age immigrants from non-western countries and the gap between labor market participation of non-western immigrants and those of Danish origin dropped by more than 9 percentage points.[32] Despite reported gains, immigrant labor market participation remains far below that of Danes, which was above 80% in 2008.[32]

The sectors that employ immigrants contrast with those that employ native Danes, with a higher proportion of immigrants concentrated in the field of manufacturing and a greater proportion of working immigrants, especially those from non-western countries of origin, being self-employed. Immigrant self-employment is concentrated in service sectors such as restaurants, hotels, retail, and repair services. Immigrants are also more likely to be employed in larger companies with 100 employees or more as opposed to mid-sized and small companies.[33] A gap in employment continues to be found between highly skilled immigrants and Danes, with more than one fifth of highly educated immigrants working in jobs below their skill level, indicating that there may be more factors than the employment disincentive of welfare benefits to account for this pattern.[31]

| Country of birth | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 82,3 | 78,9 | 80 | 80 | 82 | |

| 83,1 | 80,9 | 81 | 78 | 82 | |

| 73,1 | 75,5 | 76 | 78 | 79 | |

| 72,1 | 72,2 | 74 | 75 | 76 | |

| 74,2 | 72,7 | 74 | 75 | 75 | |

| 71,4 | 73,0 | 73 | 73 | 75 | |

| 68,7 | 71,0 | 72 | 73 | 75 | |

| 64,5 | 68,6 | 70 | 71 | 74 | |

| 70,6 | 70,6 | 73 | 74 | 74 | |

| 74,4 | 70,4 | 71 | 73 | 74 | |

| 67,4 | 68,6 | 70 | 72 | 74 | |

| 72,2 | 72,6 | 73 | 73 | 74 | |

| 72,4 | 68,7 | 69 | 71 | 73 | |

| 65,5 | 66,0 | 67 | 70 | 73 | |

| 72,5 | 71,4 | 72 | 71 | 73 | |

| 65,4 | 66,7 | 68 | 70 | 72 | |

| 64,9 | 66,9 | 66 | 66 | 71 | |

| 66,1 | 70,6 | 71 | 71 | 71 | |

| 60,9 | 64,8 | 65 | 66 | 69 | |

| 62,0 | 63,3 | 64 | 66 | 69 | |

| 64,0 | 63,3 | 64 | 65 | 69 | |

| 62,9 | 65,9 | 65 | 66 | 68 | |

| 64,3 | 65,5 | 66 | 65 | 65 | |

| 56,5 | 57,0 | 57 | 59 | 65 | |

| 61,8 | 60,6 | 61 | 61 | 64 | |

| 52,7 | 52,7 | 54 | 54 | 59 | |

| 53,1 | 52,8 | 53 | 55 | 57 | |

| 49,0 | 47,5 | 49 | 51 | 55 | |

| 49,6 | 47,4 | 48 | 51 | 54 | |

| 49,0 | 48,6 | 51 | 52 | 54 | |

| 50,7 | 48,3 | 49 | 50 | 52 | |

| 39,1 | 39,2 | 41 | 44 | 49 | |

| 32,8 | 33,2 | 35 | 37 | 40 | |

| 22,8 | 14,0 | 12 | 23 | 39 | |

| 30,4 | 31,9 | 34 | 36 | 39 | |

| 27,6 | 26,2 | 28 | 31 | 38 | |

Welfare benefits and the "unemployment trap"

One explanation for this gap in employment between immigrant populations and Danes has been the high proportion of immigrants with low levels of education which correlate with lower wages. Studies have found that the difference in income and social benefits would only be marginally different for more than one third of the immigrant population, which makes immigrants vulnerable to the "unemployment trap."[33] Denmark offers some of the highest unemployment benefits of OECD countries, which have been argued to act as a disincentive for labor market participation, particularly within low-skilled immigrant populations.[31] One analysis by the Rockwool Foundation based on surveys of immigrants in 1999 and 2001 found that 36% of non-western immigrants and their descendants employed full-time earned 500 Danish Kroner in disposable income per month below what they would receive had they been full-time unemployed. The study found that wages above the benefits of unemployment not only incentivized workers to maintain their employment, but was also linked to immigrants’ job search activity, with immigrants with the greatest perspective income gains through employment being the most active in searching for and applying for jobs.[33]

| Country of birth | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 77,5 | 91,6 | 89,6 | 77,9 | 67,4 | |

| 74,7 | 74,8 | 72,1 | 68,5 | 64,4 | |

| 70,9 | 69,5 | 67,4 | 65,5 | 63,6 | |

| 68,8 | 67,5 | 65,4 | 63,4 | 61,8 | |

| 63,2 | 62,4 | 59,4 | 56,3 | 53,0 | |

| 50,2 | 50,1 | 49,1 | 48,2 | 47,3 | |

| 54,3 | 52,5 | 50,7 | 49,6 | 47,0 | |

| 45,7 | 45,5 | 43,7 | 42,3 | 41,0 | |

| 49,4 | 46,6 | 43,6 | 42,3 | 40,7 | |

| 45,5 | 44,3 | 42,0 | 40,4 | 39,1 | |

| 40,4 | 39,6 | 38,8 | 37,4 | 36,3 | |

| 33,2 | 32,9 | 31,4 | 29,8 | 27,8 | |

| 32,6 | 31,6 | 29,3 | 28,3 | 27,0 | |

| 31,7 | 32,9 | 30,6 | 28,4 | 26,3 | |

| 27,0 | 25,7 | 24,1 | 22,9 | 21,9 | |

| 21,2 | 20,9 | 20,5 | 20,4 | 20,0 | |

| 20,6 | 19,7 | 18,9 | 18,0 | 16,9 | |

| 19,4 | 18,6 | 17,4 | 17,1 | 16,8 | |

| 21,0 | 19,7 | 18,6 | 17,1 | 16,4 | |

| 16,3 | 16,5 | 15,9 | 15,9 | 15,1 | |

| 19,5 | 18,2 | 17,2 | 16,1 | 14,8 | |

| 17,8 | 18,4 | 16,7 | 15,9 | 14,8 | |

| 21,6 | 17,0 | 16,8 | 15,5 | 14,6 | |

| 16,9 | 16,3 | 15,1 | 15,1 | 14,1 | |

| 15,2 | 14,6 | 13,3 | 12,8 | 12,0 | |

| 14,2 | 13,6 | 12,8 | 12,3 | 11,9 | |

| 14,9 | 14,2 | 13,4 | 12,7 | 11,4 | |

| 13,2 | 12,4 | 11,7 | 11,0 | 10,7 | |

| 12,2 | 11,4 | 10,7 | 10,1 | 9,2 | |

| 11,0 | - | 8,4 | 7,9 | 7,5 | |

Labor market structure

Another explanation relates to the structure of the Danish labor market, which consists primarily of highly skilled jobs with firm-specific training and few low skill or entry-level positions. In addition, many entry-level jobs require vocational training which most immigrants lack. Denmark's labor market is also characterized as flexible, with high levels of employee turn over. Immigrants' lack of language skills and cultural knowledge have been argued to be linked to their shorter periods of employment and lengthier dependency on unemployment benefits.[36] The length of time an immigrant has lived in Denmark, their Danish language skills, and their associations with native Danes have been identified as being positively linked to immigrant employment.[33] The connection between the gender of immigrants and these as well as additional factors, such as parenthood, and the level of Danish language skills, and the importance of education and employment qualifications differ among male and female immigrants.[33] One study found that men's language skills and qualifications were of less importance than for women immigrants applying for jobs. It was also found that immigrant women with small children were less likely to be employed than those without.[33]

Ethnic discrimination

In addition to these theories, employment discrimination against immigrants has been identified as a possible barrier to workforce participation. A 2001 Rockwool Foundation study[33] based on opinion surveys asked immigrants, second generation immigrants, and native Danes if they had been turned down from a job in the last five years and if they believed that they had been discriminated against. 35 percent of immigrant and immigrant descendant respondents had been turned down for a job and felt they had been discriminated against on the basis of ethnicity. Furthermore, 39% of immigrants and immigrant descendants employed at the time of the survey felt that they had been victims of discrimination at some time since entering the workforce.

Spatial segregation

Preventing spatial segregation and ethnic enclaves has been a growing concern in Denmark since the 1980s. Denmark's first dispersal act was passed in 1986 and enforced the geographic dispersal of arriving refugee populations across the 13 Danish counties.[31] The Integration Act of 1998 reassigned primary responsibility to find local housing for refugees and organize programs to introduce refugees to Danish society to municipalities.[37] The 1998 legislation also tied immigrant introductory programs and welfare benefits to residing in their assigned municipality in order to discourage relocation.[31]

Legislation to further promote integration of immigrant populations, titled "A Change for Everyone" was passed in May 2005. Part of the aim of this legislation was to combat ethnic ghettoization of neighborhoods.[38] This act gave municipalities the right to deny housing to applicants on housing waiting lists that had received public benefits for 6 months or more in order to encourage unemployed immigrant populations to accept housing offers outside of areas with high concentrations of immigrants in an effort to diversify the composition of tenants in urban areas. This legislation aimed to balance housing waiting lists in cities such as Copenhagen with existing vacancies in geographic regions such as Jutland.[39]

The Danish Ghetto Policy has become a major topic of political discussion since 2002. A publication by the Danish Housing Sector[40] describes considerations of government policies concerning ghettos in saying:

Parallel societies create constraints rather than opportunities, have a negative effect on immigration, counteract efforts in the areas of employment and social welfare and leave children and young people with poor job and education prospects.

As of June 2013, residential areas are legally considered ghettos if it satisfies three out of the following five criteria: residents of the area's income is 55% or below the region's income average, 50% of residents between the ages of 30 and 59 have not been educated past primary school, 2.7% of residents have been convicted of a crime, more than 50% of residents have non-western countries of origin, and 40% of adults between the ages of 18 and 64 are not working or in school.[41] Classifying residential areas as ghettos is part of an effort to better pinpoint areas in need of social services to improve residents' quality of life.[41] As of November 2014, 34 residential areas nationwide qualify as ghettos, with 6 of these residential areas located within the city of Copenhagen.[41]

In 2018, the Lars Løkke Rasmussen III Cabinet published a proposal titled "Ét Danmark uden parallelsamfund - Ingen ghettoer i 2030" ("One Denmark without parallel societies - No ghettos by 2030"). Examples of specific proposals are demolishment of existing neighbourhoods, requiring daycare institutions to accept at most 30% of children from ghettos, and allowing police to designate areas as "skærpede strafzoner", such that certain crimes committed within them are punished more severely than crimes committed elsewhere.[42]

Economic impact of immigration

The cost of integrating Denmark's immigrant population both as socio-cultural and economic members of the Danish population has been used as a justification for the passage of increasingly stringent immigration and refugee policy.[5][30] Recent numbers calculating the cost of immigration welfare benefits to the Danish economy are debated due to the number of complex factors involved.[20] One 1997 report from the Ministry for Immigrants, Refugees and Immigration stated that the total cost of immigrants and their descendants to the state, taking into account their tax contributions as well, was 10 billion Danish Kroner.[20] The following section explores the conceptual and numeric economic costs and gains that Denmark has experienced as its immigrant population has increased in recent years.[5]

Public finances

According to the Danish Ministry of Finance, non-Western immigration will cost the public expenses 33 billion DKK annually (about 4.4 billion euro) for the foreseeable future due to the low levels of employment. Therefore, they result in higher expenses for social benefits and pay less tax. Western immigrants and their descendants contributed 14 billion DKK annually due to their high level of employment.[43]

Employment

In the 1990s Denmark was found to have the greatest gap between immigrant and native-born employment of all of the OECD countries. One study, published by the Think Tank on Integration in Denmark[44] found

"The inadequate integration of foreigners in the labor market will cost the public sector some 23 billion Danish Kroner annually from the year 2005."

A 1996 study of positive and negative net transfers to and from the Danish Public Sector found that although immigrants contributed a positive transfer to the national public sector tax base, they posed a negative transfer at the county and municipal level as primarily recipients of rather than contributors to public sector benefits. Immigrants from non-western countries of origin posed the greatest cost to the public sector, with the smallest positive contribution when compared to native Dane and second generation immigrants at the state level and the largest cost at the county, municipal, and unemployment insurance levels of the public sector budget.[45] The particularly high cost to municipalities can be explained in part by municipalities’ responsibility to design and fund the integration of their resident immigrant populations.[46] This same 1996 study [45] found that the length of time immigrants live in Denmark can remediate some of these costs, with an increase in the number of years an immigrant lives in Denmark correlating a larger net contribution to the national, county, and municipal levels of the public sector. Despite this finding, the greater the number of years an immigrant lived in Denmark also correlated with a greater cost in unemployment insurance. A study published in 2003 found that in order for the net contribution of working age immigrants to meet their net costs to the public sector it would require 60% labor force participation within the population.[47] Statistics such as these motivated the Danish government to pass the first Integration Act of 1999, which articulated labor market participation as a measurement of immigrant integration.[31]

Wages

Denmark does not have a nationally mandated minimum wage, rather trade unions regulate pay by lobbying for wage standards within their specific sectors.[45] The strength of trade unions to influence wages relies upon their representation of the labor force and a lack of competition for lower wages.[5] As immigration and free movement from European Union member countries have increased, trade unions and economic experts have speculated that an increase in workers outside of trade unions, especially in the unskilled labor market, will lead to a weakening of labor union bargaining power and a drop in native Danes' wages.[5]

Pension

Many scholars[46][48] have identified the influx of a younger immigrant population as a posing a possible economic benefit to the aging Danish population and its declining fertility by contributing to the tax base as a growing number of native Danes reach retirement age and collect their state pensions. This issue remains contested, however, due to the low rates of employment among immigrant populations with some scholars suggesting that the best solution to counter the aging Danish population coupled with the economic burdens of immigrants on the public sector would be longer labor market participation through an increase in retirement age.[48]

Crime

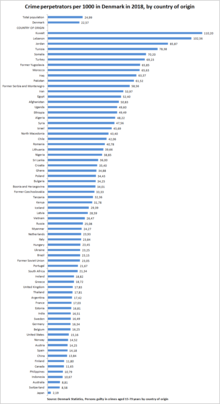

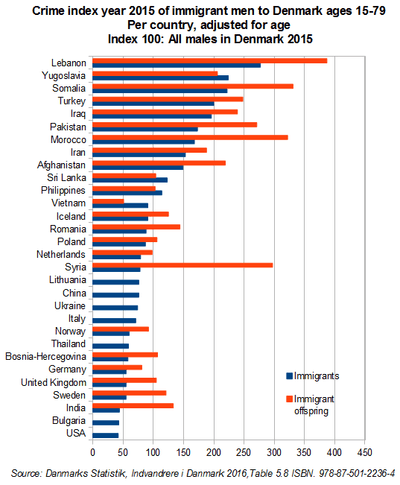

Immigrants and men and women of immigrant descent in Denmark are over-represented in crime statistics. A study of crime statistics from 1990 to 2001 found greater proportion of non-Western immigrant and descendant populations are convicted of committing a crime than Western immigrants and descendants and their Danish peers. The same study suggested that descendants of immigrants were found to have a slightly higher crime rate than immigrant populations.[49]

Studies have found that the types of crime that Danish nationals and immigrants and their descendants are found guilty of committing differ. A study of crime by country of origin from 1995 to 2000 found that Danes are more likely to violate the Road Traffic Act, whereas immigrants and descendants have a higher proportion of convictions for property violations and crimes of violence than Danes.[49]

The incidence of crime within male second-generation populations of non-Western descent has been rising, with more than a 60% increase in crimes committed by members of this demographic group between 2007 and 2012. This growing crime rate has put pressure on politicians to design new legislature to deter criminal activity. In February 2014, the Danish Minister of Justice suggested that child support be cut to immigrant families with youth found guilty of a crime.[53] Currently, an immigrant convicted of a serious crime is excluded from obtaining right to permanent residence.[20]

Immigration and integration scholars have noted that differences in crime between native-born citizens and immigrants and their descendants may indicate a lack of agreement with common societal rules and norms and therefore an indication of poor integration of foreigners into the greater population.[54] Other explanations for the higher rates of arrest and conviction rates for immigrants have been the age demographic differences, Islam, different crime patterns, different confessional patterns, and ethnic profiling by law enforcement officials.[55] Involvement in criminal activity has been linked to age and the foreign-born population of Denmark includes a greater proportion of adolescents than the Danish population.[55] The types of crimes committed may impact arrest and sentencing,[55][56] and as the previously mentioned study pointed out, differences exist in the types of crime committed by demographic groups.[49] A willingness to confess has been linked to dropped charges and acquittals. Two studies comparing the confession patterns of Danish and foreign born individuals found that individuals of a Danish background were twice as likely to confess to criminal charges than those of an immigrant background.[55] Finally, a qualitative study of Danish police indicated that the ethnicity of an individual was a factor in police's stop-and-search procedure, indicating that the number of arrests of immigrants and ethnic minority citizens in Denmark may be inflated due to a greater suspicion of the criminal actions of such individuals.[57]

Danish national police reported in 2012 that conviction rates per 1000 residents in Denmark were: 12.9 for Danish citizens, 114.4 for Somali citizens and 54.3 for citizens of other countries.[58]

According to a 2015 report by Statistics Denmark, men born abroad had a 43% higher crime rate compared to the average of all men in Denmark. The highest rates were recorded from males from Lebanon, Somalia, Morocco, Syria and Pakistan. For male descendants of non-Western immigrants, the discrepancy was greater at 144%.[59]

According to the 2016 report by Statistics Denmark, the crime rate of non-Western male migrants was about three times that of the male population in Denmark. When correction for the greater proportion youth among non-Western migrants are taken into account and is adjusted for, the crime rate was two and half times that of the general male population.[60] Male immigrants and male descendants from EU countries were among males with the lowest crime rate. When corrected for age, male immigrants from Germany, Sweden, Italy and the United Kingdom crime indices of less than half (43-48%) the average of all males in Denmark. Descendants from nearly all countries showed an over-representation, except descendants with roots in Iceland, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. Syrian male descendants stand out where their crime rate is three times that of Syrian immigrants.[61]

At 4%, male migrants aged 15–64 with non-Western backgrounds had twice the conviction rate against the Danish Penal Code in 2018, compared to 2% for Danish men. In a given year, about 13% of all male descendants of non-Western migrants aged 17–24 are convicted against the penal code.[62]

In the 2018-2020 period, 83 people were denied Danish citizenship because they had committed serious crime. Amon those were people who had received court sentences for gang crime, violence against children and sexual offenses. People who have received a prison sentence of at least one year are barred from receiving citizenship, along with people who have received a prison sentence of at least three months for a crime against a person.[63]

Prisoner population

In 2017, 30% of the prison population were foreign nationals with the largest group being Romanian citizens, followed by Somali, Turkish and Lithuanian citizens. On 1 July 2017, there were 3403 inmates and 2382 of those were Danish citizens. In 2017, the share of immigrants, foreigners and descendants of immigrants constituted 43.5% of the prison population.[64]

According to statistics collected in November 2018 non-Danish immigrants constituted 44.3% of the prison population where 13.5% were foreigners, 16.5% were immigrants and 14.2% were descendants of immigrants. In Copenhagen prisons the share was higher at 66.3%.[65]

Language

In 1973, the first policy regarding immigrant language acquisition was enacted. This law required all foreign workers in Denmark to complete 40 hours of language instruction within a month of their arrival in Denmark. The Ministry of Social Affairs expanded this requirement in 1975 from 40 hours to 180 hours of language instruction accompanied by 40 hours of courses to introduce workers to norms of Danish society.[66] Today, all applicants for permanent residency in Denmark must sign a Declaration on Integration and Active Citizenship in Danish Society[67] which includes the following provision:

"I understand and accept that the Danish language and knowledge of the Danish society is the key to a good and active life in Denmark. I will therefore do my best to learn Danish and acquire knowledge about the Danish society as soon as possible. I understand and accept that I can learn Danish by attending Danish classes offered to me by the district council."

Immigrants that have been granted residence permits based on family reunification are required to pass a Danish language test within six months of the date they registered at the National Register of Persons. Reunified spouses benefit from passing an optional second level of the language test, which upon passing, will reduce the amount of monetary collateral their partner has to provide as a requirement of their reunification.[68]

Education

Immigrants arriving to Denmark have lower average levels of education than their Danish counterparts.[69] Despite low levels of education within Denmark's immigrant population, enrollment of immigrants in continuing education is higher than other nations with similar immigrant demographics, such as Germany.[69]

Until 2006, Danish immigrant pupils had the privilege to receive instruction of their mother tongue. This practice was discontinued as it was found in a study of 450 immigrant pupils that such instruction did not improve test scores in numeracy or literacy in the PISA tests.[70]

Parents of non-Western education have a 60% share with only primary education, compared to 20% of Danes.[62]

Enrollment

During the 2008–2009 school year, immigrants and descendants of immigrants constituted 10% of the children enrolled in primary and secondary school.[32] Gaps exist between immigrant and immigrant descendants' and Danish enrollment in secondary education between the ages of 16 and 19 for both men and women.[32] In addition to differences in enrollment in secondary education, immigrant students are more often enrolling in Vocational secondary education in Denmark rather than other forms of Secondary education in Denmark, which is a more popular educational pathway among their Danish peers.[71] Second generation immigrants, however are enrolling in higher education at or above the level of their native Danish peers.[32] In 2009, the number of women descendants of immigrants age 20 to 24 enrolled in higher education outnumbered Danish women for the first time and the number of descendant men age 20 to 24 enrolled in higher education was equal to that of Danish men.[32]

Achievement gaps

On average, immigrant students have weaker performance levels in reading, math, and science than their Danish peers at the end of compulsory education[71] One analysis of Denmark's results from the OECD's 2003 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test[72] revealed that reading scores of Danish natives were much higher than those of immigrant and descendant students from Turkey, Lebanon, Pakistan, and former Yugoslavia, the four main countries of origin in the study. It was found that demographic characteristics such as the student's gender, number of siblings, language spoken at home, home education resources, the number of books in the home, parents' level of education, parents' income and occupation, and parents' labor market experience explained between 40 and 65% of the achievement gap between immigrant and native Dane test scores.[72] Although it was predicted that second generation students would outperform their first generation counterparts, the study found that country of origin should be considered when evaluating second generation academic performance, with Pakistani and Lebanese second generation students performing better than first generation students, but Turkish and Yugoslavian second generation students performing at the same level as first generation students.[72]

In 2012, according to PISA København, half of immigrant boys left primary education functionally illiterate.[73]

In addition to the finding that student demographic characteristics concerning their family size, educational materials in the home, and their parents' socioeconomic status, the study found that schools with more than 10% immigrant students had greater achievement gaps between immigrant and descendant PISA scores and the scores of native Danish students. This indicates that school composition also has a significant effect on immigrant student achievement.[72]

According to Statistics Denmark, pupils with Vietnamese (highest), Danish, Sri Lankan and Iranian backgrounds scored at the top and pupils with backgrounds from Morocco, Somalia, Turkey and Lebanon (lowest) scored at the bottom.[74] For all groups girls scored better than boys.[74]

The PISA Etnisk 2015 study indicated that the achievement gap of first-generation immigrants had narrowed to the level of second-generation immigrants from 2009 to 2015, but that the scores of second-generation immigrants had not improved in the same period.[75]

According to Statistics Denmark 2016, school grades do not improve for non-Western between the second and third generation, where the grades are on average (5,6 males, 6,3) lower compared to Danish pupils (6.9 males, 7.7 females).[76]

A study by the Ministry of Immigration and Integration in 2018 found, among other findings in the study, that same-aged children and youth retain a disparity of results depending on immigration status, especially in the case of being a descendant of immigrant, adding a number of possible causes, such as a significantly lower average age for immigrant mothers, which by itself was theorized by the study to be because of increased restrictions to family reunification. The study also concluded, however that "the amount of children that are descendants of immigrants is today so low that it isn't possible to predict the future demographic behavior for this group."[77]

This was also covered under an article from the Danish newspaper, Berlingske, which initially proclaimed the study as "disproving the notion that with the right kind of help, immigrants and their descendants will eventually tend to the same levels of education and employments as Danes. Berlingske later corrected this to clarify that this was, in fact, an interpretation from the politicians in the article, and not the statement of the Ministry. It also corrected the statement that later generations were being compared, when, in fact, the study was covering same-aged youths, regardless of immigration generation, among other confounding factors, such as the relatively low number of descendants and immigrants.[78]

Religious education

Religious Education is a compulsory subject in Danish public schools.[26][79] In elementary schools, this class is often titled Kristendomskundskab ("Knowledge about Christianity"), but is perceived to be a culturally neutral course in which students learn of the historical religious and cultural values of Denmark, rather than elaborating on the core teachings of the Lutheran Folk Church as it had until the 1970s.[26] Other or "foreign religions" were added as compulsory subjects in the Danish curriculum in 1975,[26] but are taught exclusively at the upper grade levels,[79] either within the Christian Studies course or in other courses such as History.[26]

Politics

Immigration as a political issue

Immigration and asylum gained increasing political salience in the 1990s and 2000s. Prior to the 1980s, immigration was not an issue that was included in political party manifestos.[80] Immigration was first mentioned in political party agendas in 1981, when less than 1% of political agenda content was devoted to the issue. In 1987, 2.8% of Danish political party manifesto content mentioned immigration, after which mentions of immigration decreased below 1% until 1994 when the percentage jumped to 4.8% and then continued to increase to 7.7% during the 1998 election cycle and to 13.5% during the 2001 elections.[80] When Danes were surveyed in 2001 about the most important issues politicians should address in the coming election, 51% of respondents listed immigrant and refugee populations.[81] A disagreement on the issue of immigration within the coalition government in power, consisting of the Social Democratic Party and the Social Liberals, has been cited as a major cause of the Social Liberal Party's rise to power in coalition with the Danish Conservative People's Party and the Danish People's Party in the 2001 parliamentary elections.[80]

Danish People's Party and immigration

In 2002, several of the Danish People's Party demands for stricter limitations to Denmark's family reunification policy were introduced into law.[82] A new policy stipulated that spouses must be 24 years of age or older in order to qualify for spouse reunification, now commonly referred to as the 24-year rule. In addition, the Danish immigration authorities were tasked with assessing if each member of the couple applying for spouse reunification had a greater attachment to Denmark or to another nation. Spouse reunification was denied to any applicants who had received Danish social assistance within a year of their application and the person already residing in Denmark was required to provide bank documentation that he or she could provide financial collateral for public expenses to support his or her partner. A housing requirement mandated a space of 20 square meters per person in the accommodations provided by the current resident of Denmark.[82] As a result of these policy changes, the number of family reunification permits granted fell from 13,000 in 2001 to less than 5,000 in 2005.[83]

Since the 2001 election, the Danish People's Party has become increasingly popular as it has focused its political agenda on issues of welfare and immigration. In the 2005 parliamentary election, the party increased their number of seats in parliament from 22 to 24 after winning 13.2% of the public vote. In the subsequent 2007 parliamentary elections, the Danish People's party again saw increased support with 13.9% of the vote leading them to gain one additional seat in parliament[84]

References

- Jensen, Peter; Pederson, Peder J. (December 1, 2007). "To Stay or Not to Stay? Out Migration of Immigrants to Denmark". International Migration. 45 (5): 94. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2007.00428.x.

- Wadesnjo, Eskil (2000). "Immigration, the Labor Market and Public Finances in Denmark". Swedish Economic Policy. 7: 61.

- Nannestad, Peter (September 2004). "Immigration as a challenge to the Danish welfare state? ☆". European Journal of Political Economy. 20 (3): 758. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2004.03.003.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Husted, Lief; Nielsen, Helena Skyt; Rosholm, Michael; Smith, Nina (December 1999). "Employment and Wage Assimilation of Male First Generation Immigrants in Denmark". International Journal of Manpower. 22 (1–2): 40. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.200.4546. doi:10.1108/01437720110386377.

- Brochmann, Grete; Hagelund, Anniken; Borevi, Karin; Vad Jonsson, Heidi (2012). Immigration Policy and the Scandinavian Welfare State, 1945-2010. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 9.

- Grunnet, Henrik; Jensen, Jakob. "Statistical Overview Migration and Asylum 2012" (PDF). The Danish Immigration Service. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- "Historiker om Margrethes danskheds-udtalelse: - Hun har fulgt folkesjælens bekymringer". TV2 (Denmark). 23 October 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- "Dronning Margrethe om integration: »Det er ikke en naturlov, at man bliver dansker af at bo i Danmark«". Berlingske Tidende. 22 October 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- December 7, CBC Radio ·. "Denmark treating migrants like 'inferior race' by sending them to remote island: MP | CBC Radio". CBC. Retrieved 2018-12-15.

- "Publikation: Indvandrere i Danmark 2018 revideret". www.dst.dk (in Danish). Statistics Denmark. p. 26. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- Støjberg, Inger. "Støjberg: Derfor skal uønskede udlændinge bo på en ø". www.bt.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 2018-12-15.

- "Flertal for et udrejsecenter på Lindholm - sådan fordelte stemmerne sig". TV ØST (in Danish). 2018-12-19. Retrieved 2018-12-23.

- "Nu skal man give hånd for at få statsborgerskab". Berlingske.dk (in Danish). 2018-12-20. Retrieved 2018-12-23.

- "Flere flygtninge forlader Danmark end der kommer hertil". DR (in Danish). 2020-05-04. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- "Over 600 asylansøgere får afslag efter snyd med deres identitet". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 2017-10-12.

- Doyle, Alister (21 April 2016). "Child brides sometimes tolerated in Nordic asylum centers despite bans". Reuters (Oslo). Retrieved 22 April 2016.

In February, Danish Integration Minister Inger Stojberg said that she would "stop housing child brides in asylum centers" after a review found dozens of cases of girls living with older men. Couples younger than 18 would not be allowed to live together without "exceptional reasons", said Sarah Andersen, spokeswoman for the Integration Ministry. "There will never be exceptions in cases where one side is below the age of 15," she said. In Denmark, 15 is the minimum age for sex and for marrying with a special permit.

- Parallelsamfund i Danmark / Økonomisk Analyse nr. 30. Ministry for economic affairs and the interior. February 2018. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "Population at the first day of the Quarter by Ancestry, Time, and Country of Origin 2014". Statistics Denmark. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- Kuttner, Robert (2008). "The Copenhagen Consensus". Foreign Affairs. 87 (2): 86.

- Ostergaard-Nielsen, Eva (2003). "Counting the Cost: Denmark's Changing Migration Policies". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 27 (2): 448–454. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00457.

- https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik

- "POPULATION AT THE FIRST DAY OF THE QUARTER BY REGION, SEX, AGE (5 YEARS AGE GROUPS), ANCESTRY AND COUNTRY OF ORIGIN". Statistics Denmark.

- Denmark country profile- [Euro-Islam.info] and Muslimpopulation.com – Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "2013 Report on International Religious Freedom -Denmark". United States Department of State. July 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "2010 Report on International Religious Freedom -Denmark". United States Department of State. 17 November 2010. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Jensen, Tim (2007). "Religious pluralism in Denmark". Res Cogitans Journal of Philosophy. 2 (4).

- Andersen, Joel; Antalikova, Radka (2014). "Framing (implicitly) matters: The role of religion in attitudes toward immigrants and Muslims in Denmark". Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 55 (6): 593–600. doi:10.1111/sjop.12161. PMID 25231272.

- Jensen, Tina Gudrun (2008). "To Be 'Danish', Becoming 'Muslim': Contestations of National Identity?". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 34 (3): 389–409. doi:10.1080/13691830701880210.

- Kærgård, Niels (2015). "From religion to economic acting". Department of Food and Resource Economics University of Copenhagen.

- Rytter, Mikkel; Pedersen, Marianne Holm (2014). "A decade of suspicion: Islam and Muslims in Denmark after 9/11". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 37 (13): 2303–2321. doi:10.1080/01419870.2013.821148.

- Liebig, Thomas (March 5, 2007). "The Labor Market Integration of Immigrants in Denmark" (PDF). OECD Social, Employment, and Migration Working Papers. 50.

- Ministry of Refugee, Immigration, and Integration Affairs (September 2010). "Statistical Overview of Integration: Population, Education, and Employment" (PDF): 9–10. Retrieved 12 January 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mathiessen, Poul Chr. (2009). Immigration to Denmark: An overview of the Research Carried Out from 1999 to 2006 by the Rockwool Foundation Research Unit. Odense, Denmark: The Rockwool Foundation Research Unit University Press of Southern Denmark. ISBN 9788776744137.

- https://www.dst.dk/da/Statistik/Publikationer/VisPub?pid=1174

- https://www.dst.dk/da/Statistik/Publikationer/VisPub?pid=1174

- Brodmann, Stefanie; Polavieja, Javier G. (2011). "Immigrants in Denmark: Access to Employment, Class Attainment and Earnings in a High-Skilled Economy". International Migration. 49 (1): 58–90. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00608.x.

- Vad Jonsson, Heidi; Petersen, Klaus. Immigration Policy and the Scandinavian Welfare State 1945-2010. Chapter 3 Denmark: A National Welfare State Meets the World: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 128.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Penninx, Rinus (2007). "Case Study on Housing: Copenhagen, Denmark". European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

- Erlandsen, Espen; Lundsgaard, Jens; Huefner, Felix (2006). "The Danish Housing Market: Less Subsidy and More Flexibility". OECD Economics Department Working Papers.

- "The Danish Social Housing Sector" (PDF). www.mbbl.dk. Ministry of Housing, Urban and Rural Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- Stanners, Peter. "Government Changes What is Means to Come from a Ghetto". The Copenhagen Post. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- "Regeringen vil gøre op med parallelsamfund". regeringen.dk. 1 March 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- "Ikke-vestlig indvandring og efterkommere koster varigt 33 mia. kr. om året frem til år 2100". Finansministeriet (in Danish). Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- The Think Tank on Integration in Denmark (2002). "Immigration, Integration, and the National Economy". The Ministry of Refugee, Immigration and Integration Affairs: 6.

- Wadensjo, Eskil; Orrje, Helena (2002). Immigration and the Public Sector in Denmark. Denmark: Aarhus University Press. ISBN 9788772888965.

- Clausen, Jens; Hienesen, Eskil; Hummelgaard, Hans; Husted, Lief; Rosholm, Michael (2009). "The effect of integration policies on the time until regular employment of newly arrived immigrants: Evidence from Denmark". Labour Economics. 16 (4): 409–417. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.3303. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2008.12.006.

- Storesletten, Kjetil (2003). "Implications of Immigration – A net present value calculation". Scandinavian Journal of Economics. 105 (3): 487–506. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.201.807. doi:10.1111/1467-9442.t01-2-00009.

- Andersen, Torben M; Pedersen, Lars Haagen (2006). "FINANCIAL RESTRAINTS IN A MATURE WELFARE STATE—THE CASE OF DENMARK". Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 22 (3): 313–329. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grj019.

- Entorf, Horst; Larsen, Claus (2004), "Immigration and Crime in Germany and Denmark", in Tranæs, Torben; Zimmermann, Klaus F. (eds.), Migrants, work, and the welfare state, Odense, Denmark: University Press of Southern Denmark and the Rockwool Foundation Research Unit, pp. 285–317, ISBN 9788778387745.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Pdf.

- Indvandrere i Danmark 2016. [Statistics Denmark]]. 2016. pp. 81, 84. ISBN 978-87-501-2236-4.

- https://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?MainTable=STRAFNA3&TabStrip=Select&PLanguage=1&FF=20

- https://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?MainTable=FOLK2&PLanguage=1&PXSId=0&wsid=cftree

- Admin (18 February 2014). "More Immigrant Youngsters Becoming Criminals". The Copenhagen Post. Ejvind Sandal. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- Entzinger, Han; Biezeveld, Renske (2003). Benchmarking in immigration integration (Report). European Research Centre on Migration and Ethnic Relations (ERCOMER).

- Holmberg, Lars; Kyvsgaard, Britta (December 2013). "Are immigrants and their descendants discriminated against in the Danish criminal justice system?". Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention. 4 (2): 125–142. doi:10.1080/14043850310020027.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kyvsgaard, Britta (November 2001). "Kriminalitet, retshåndhævelse og etniske minoriteter". Juristen. 9. Pdf.

- Holmberg, Lars (2003). Policing stereotypes a qualitative study of police work in Denmark. Glienicke, Berlin Madison, Wisconsin: Galda und Wilch. ISBN 9783931397487.

- "Spørgsmål nr. 89 (Alm. del) fra Folketingets Udvalg for Udlændinge- og Integrationspolitik" (PDF). www.ft.dk. Folketing - The Danish Parliament. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- "Danmark: Kriminaliteten 43 prosent høyere blant mannlige innvandrere". Aftenposten (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2017-11-25.

Kriminaliteten er 43 prosent høyere blant mannlige innvandrere enn blant alle menn i landet. Øverst troner personer fra Libanon, Somalia, Marokko, Syria og Pakistan. Tallene er mye høyere for gruppen «mannlige etterkommere med ikke-vestlig bakgrunn»: For denne gruppen er kriminaliteten hele 144 prosent høyere enn blant hele den mannlige befolkningen i Danmark.

- Indvandrere i Danmark 2017 (in Danish). København. November 2017. p. 103. ISBN 9788750122821. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017.

Hvis der beregnes et ukorrigeret indeks, dvs. at antallet af dømte i en befolkningsgruppe blot sættes i relation til antallet af personer i den samme befolkningsgruppe, viser det sig fx, at mandlige efterkommere fra ikke-vestlige lande har et kriminalitetsindeks på 319. Det betyder, at denne gruppe har en overhyppighed af kriminalitet på 219 pct. i forhold til hele den mandlige befolkning, hvor indekstallet Tabel 6.6 Korrektion for alderssammensætning Metode Betydning af alderskorrektion 104 er sat til 100. Når der korrigeres for deres alderssammensætning, falder indekset til 245.

- Indvandrere i Danmark 2017 (in Danish). København. November 2017. p. 105. ISBN 9788750122821. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017.

Indvandrere og efterkommere med oprindelse i EU-lande er blandt de mænd, der har den laveste kriminalitet. Når der er korrigeret for alderssammensætningen, har fx mandlige indvandrere fra Tyskland, Sverige, Italien og Storbritannien indeks, der ligger mellem 43 pct. og 48 pct. under gennemsnittet for alle mænd. / Som det fremgår ovenfor, har efterkommere fra vestlige og fra ikke-vestlige lande et højere kriminalitetsindeks end indvandrerne. Det samme gælder også helt overvejende, når der kigges på de enkelte oprindelseslande. Men der er enkelte undtagelser som fx Sri Lanka, Vietnam og Island. Særlig markant er forskellen for mænd med oprindelse i Syrien. Her er indekset for efterkommere mere end tre gange så højt som for indvandrere når der er foretaget korrektion for alderssammensætningen..

- "GRAFIK Indvandrede og efterkommere halter efter etniske danskere". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- "83 kriminelle udlændinge udelukket fra dansk statsborgerskab". DR (in Danish). 2020-08-14. Retrieved 2020-08-16.

- "Fængselsformand: Udenlandske indsatte udfordrer os helt vildt". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 2019-10-03.

- Nielsen, Jens Beck (2020-03-02). "Stadig flere indsatte i landets fængsler og arresthuse har udenlandsk baggrund". Berlingske.dk (in Danish). Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 2020-03-08.

- Vad Jonsson, Heidi; Petersen, Klaus. Immigration Policy and the Scandinavian Welfare State 1945-2010. Chapter 3 Denmark: A National Welfare State Meets the World: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 111.CS1 maint: location (link)

- The Ministry of Refugee, Immigration and Integration Affairs. "Declaration on Integration and Active Citizenship in Danish Society". Nyidanmark.dk. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- "Test in Danish". Nyidanmark.dk. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Mathiessen, Poul Chr. (2009). Immigration to Denmark: An overview of Research Carried out from 1999 to 2006 by the Rockwool Foundation Research Unit. The Integration of non-Western immigrants in Denmark and Germany: The Rockwool Foundation Research Unit and University Press of Southern Denmark. p. 144.

- "Köpenhamn lägger ner hemspråksundervisning". Sydsvenskan (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- Nusche, Deborah; Wurzburg, Gregory; Naughton, Brena (2010). "Denmark" (PDF). OECD Reviews of Migrant Education.

- Rangvid, Beatrice Schindler (2010). "Source country differences in test score gaps: Evidence from Denmark". Education Economics. 18 (13): 269–295. doi:10.1080/09645290903094117.

- "Hver anden tosprogede dreng er funktionel analfabet". Danmarks Radio dr.dk. 20 Nov 2012. Retrieved 2017-05-21.

- "Efterkommere fra Libanon og Tyrkiet får bundkarakterer i folkeskolen" (in Danish). Retrieved 2017-05-25.

- "Pisa Etnisk: Andengenerationsindvandrere halter fortsat efter - Folkeskolen.dk". www.folkeskolen.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 2017-05-25.

- "Indvandrere i Danmark 2017". Statistics Denmark. p. 9. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Analyse om børn af efterkommere 2018". Ministry of Immigration and Integration. pp. 17 and 47. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- "Opråb fra ministre: Problemer med integration af børn af ikkevestlige indvandrere". Berlingske.dk (in Danish). 2018-12-16. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- Kosmin, Barry Alexander; Keysar, Ariela (2007). Secularism & Secularity: Contemporary International Perspectives. ISSSC.

- Green-Pederson, Christoffer; Krogstrup, Jesper (2008). "Immigration as a Political Issue in Denmark and Sweden". European Journal of Political Research. 47 (5): 619. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00777.x.

- Andersen, Jorgen Goul (2006). "Immigration and the Legitimacy of the Scandinavian Welfare State: Some Preliminary Danish Findings". AMID, Akademiet for Migrationsstudier I Danmark.

- Jensen, Andersen Goul (2007). "Restricting access to Social Protection for Immigrants in the Danish Welfare State" (PDF). Benefits. 15 (13): 258.

- "Denmark's immigration issue". BBC News. 19 February 2005. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- "Dansk Folkeparti". Den Store Dansk. Retrieved 12 January 2015.