Grammont, Haute-Saône

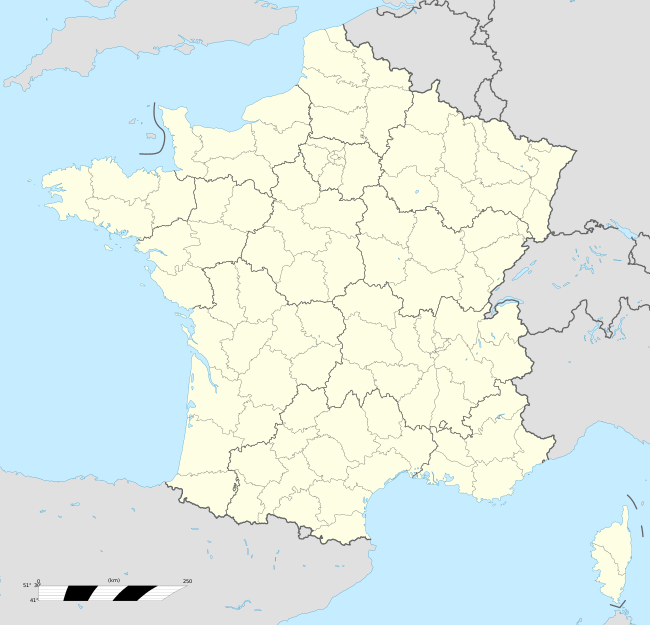

Grammont is a commune in the Haute-Saône department in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

Grammont | |

|---|---|

Grammont in 2007 | |

Coat of arms | |

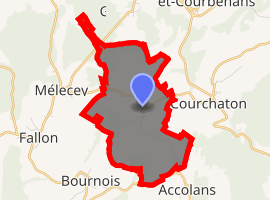

Location of Grammont

| |

Grammont  Grammont | |

| Coordinates: 47°30′56″N 6°31′02″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Bourgogne-Franche-Comté |

| Department | Haute-Saône |

| Arrondissement | Lure |

| Canton | Villersexel |

| Area 1 | 5.94 km2 (2.29 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-01-01)[1] | 66 |

| • Density | 11/km2 (29/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 70273 /70110 |

| Elevation | 283–515 m (928–1,690 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Geography

Grammont is located in the north of the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, 10 km from the capital of Canton, Villersexel and 10 km from L'Isle-sur-le-Doubs. The village's name is the combination of the adjective for "large" and the name "mount".

The average altitude of Grammont is 350 m.

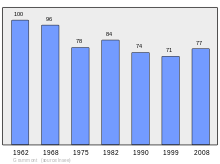

The village had 374 inhabitants at the time of the French Revolution of 1789, and 422 during the reign of King Louis-Philippe. As of February 2013, the village had only 63 inhabitants involved in mainly farming. This was down from 2007 in 1974.

History

In 1308, Guyot II Granges ("Grammont Guyot II") built a castle here. He was in homage to Count Renaud de Montbéliard. The castle was besieged, taken, burned and partially demolished by the Swiss after the battle of Héricourt on November 13, 1474.

By letters patent of 10 March 1657, the land of Grammont was erected in the county in favor of Claude-François de Grammont, honorary knight in Parliament Dole (Jura). After taking Besançon in 1674, Louis XIV made him dismantle the castles of Franche-Comté and Grammont. From 1699, the castle of Villersexel, from the family of Rye, was the new place of residence of the family.

In 1841 Grammont had 422 inhabitants. At the end of the nineteenth century, Chalon-sur-Saône and Grammont were the two largest Eastern horse fairs, with a concentration on the second which went from 400 to 800 hp by year. The Belgian and Italian armies went there sometimes for horses to their artillery; they were led on foot to the station Villersexel by grooms of these armies. The Flemish merchants went there regularly. Then came the First World War, and infectious anemia equine decimated the herd. Mules replaced them; they even harnessed cows.

At Grammont, in the early twentieth century, fairs tools and seeds that correspond to periods of intense work (plowing and haymaking) disappeared. The horse fair, in hollow period, retained all its reason for being in late winter, hence the saying: "After the fair in Grammont is sown oats."

World War II was due to the horse park with massive requisitions of the German army for the needs of the Russian front.

In 1976, the population of Grammont gave back a second wind at the fair to make it a privileged meeting place for the rural world.

Annual fair

The annual fair on 22 February, is in Geraardsbergen with a tradition of 500 years. It dates back to August 8, 1502. In the Haute-Saône, under the old regime, there are 266 fairs in 57 cities, towns or villages. In the early 19th century, 69 localities were organizing 377 fairs. A decree of 15 March 1807 is set to Grammont, the Horse Fair February 22, the Frequently Asked tools to June 6 and Frequently Asked seeds to 15 October. The fairs will culminate in the final years of the century with over 1000 fairs a year to 120 cities. A fair in common was the symbol of autonomy and village power.

Heraldry

The coat of arms of Grammont is an "Azure three queen busts complexion, and sandy hair and gold crown."

Population

In 2013, the town of Grammont had 62 inhabitants. In 1841 the population in Grammont peaked at 422, after which it declined.

References

- INSEE (in English)

- "Populations légales 2017". INSEE. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Édouard Thirria, Manuel à l'usage de l'habitant du département de la Haute-Saône, 1869 (lire en ligne [archive]), p. 184-185.

- Marcel Lanoir, Carburants rhodaniens : les schistes bitumineux, notamment dans la Haute-Saône, vol. 7, coll. (Les Études rhodaniennes, 1931), p.328.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grammont (Haute-Saône). |