Fred Hampton

Fredrick Allen Hampton (August 30, 1948 – December 4, 1969) was an American activist and revolutionary socialist.[1] He came to prominence in Chicago as chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party (BPP), and deputy chairman of the national BPP. In this capacity, he founded the Rainbow Coalition, a prominent multicultural political organization that initially included the Black Panthers, Young Patriots and the Young Lords, and an alliance among major Chicago street gangs to help them end infighting and work for social change.

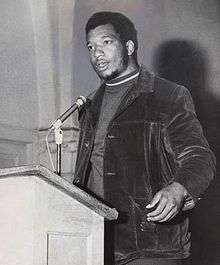

Fred Hampton | |

|---|---|

Hampton c. 1968 | |

| Born | August 30, 1948 Summit, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 4, 1969 (aged 21) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Resting place | Bethel Cemetery, Haynesville, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Citizenship | American |

| Education | Proviso East High School |

| Occupation | Activist, revolutionary |

| Years active | 1966–1969 |

| Known for | Deputy chairman of the Illinois chapter Black Panther Party |

| Political party | Black Panther Party |

| Partner(s) | Deborah Johnson |

| Children | Fred Hampton Jr. |

In 1967, Hampton was identified by the Federal Bureau of Investigation as a radical threat. The FBI tried to subvert his activities in Chicago, sowing disinformation among black progressive groups and placing a counterintelligence operative in the local Panthers. In December 1969, Hampton was shot and killed in his bed during a predawn raid at his Chicago apartment by a tactical unit of the Cook County State's Attorney's Office in conjunction with the Chicago Police Department and the Federal Bureau of Investigation; during the raid, Panther Mark Clark was also killed and several seriously wounded. In January 1970, a coroner's jury held an inquest and ruled the deaths of Hampton and Clark to be justifiable homicide.[2][3][4][5]

A civil lawsuit was later filed on behalf of the survivors and the relatives of Hampton and Clark. It was resolved in 1982 by a settlement of $1.85 million; the City of Chicago, Cook County, and the federal government each paid one-third to a group of nine plaintiffs. Given revelations about the illegal COINTELPRO program and documents associated with the killings, scholars now widely consider Hampton's death an assassination under the FBI's initiative.[6][7][8]

Early life and youth

Hampton was born on August 30, 1948, in present-day Summit, Illinois, and grew up in Maywood, both suburbs of Chicago. His parents had moved north from Louisiana, as part of the Great Migration of African Americans in the early 20th century out of the South. They both worked at the Argo Starch Company. As a youth, Hampton was gifted both in the classroom and athletically, and dreamed of playing center field for the New York Yankees. He graduated from Proviso East High School with honors in 1966 and enrolled at Triton Junior College in nearby River Grove, Illinois, where he majored in pre-law. He planned to become more familiar with the legal system to use it as a defense against police. When he and fellow Black Panthers later followed police in his community supervision program, watching out for police brutality, they used his knowledge of law as a defense.

Hampton became active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and assumed leadership of its West Suburban Branch's Youth Council. In his capacity as an NAACP youth organizer, he began to demonstrate natural leadership abilities; from a community of 27,000, he was able to muster a youth group 500-members strong. He worked to get more and better recreational facilities established in the neighborhoods and to improve educational resources for Maywood's impoverished black community. Through his involvement with the NAACP, Hampton hoped to achieve social change through community organizing and nonviolent activism.[9]

Chicago

—Fred Hampton on solidarity.[10]

About the same time that Hampton was successfully organizing young African Americans for the NAACP, the Black Panther Party (BPP) was rising to national prominence. Hampton was quickly attracted to the Black Panthers' approach, which was based on a Ten-Point Program that integrated black self-determination with class and economic critique from Maoism. Hampton joined the Party and relocated to downtown Chicago. In November 1968 he joined the Party's nascent Illinois chapter, founded in late 1967 by Bob Brown, a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organizer.

Over the next year, Hampton and his friend and associates made a number of significant achievements in Chicago. Perhaps his most important was his brokering of a nonaggression pact among Chicago's most powerful street gangs. Emphasizing that racial and ethnic conflict among gangs would only keep its members entrenched in poverty, Hampton strove to forge a class-conscious, multiracial alliance among the BPP, the neo-confederate Young Patriots Organization, and the Young Lords under the leadership of Jose Cha Cha Jimenez, leading to the Rainbow Coalition.

Hampton met the Young Lords Chicago's Lincoln Park neighborhood the day after they were in the news for occupying a police community workshop at the Chicago 18th District Police Station. He was arrested twice with Jimenez at the Wicker Park Welfare Office, and both were charged with "mob action" at a peaceful picket of the office. Later, the Rainbow Coalition was joined nationwide by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Brown Berets, A.I.M., and the Red Guard Party.[11][12] In May 1969, Hampton called a press conference to announce that this "rainbow coalition" had formed. It was a phrase Hampton coined and Jesse Jackson later popularized, eventually using the name for his own, unrelated coalition, Rainbow/PUSH.[13]

Hampton rose quickly in the Black Panthers, based on his organizing skills, substantial oratorical gifts, and personal charisma. Once he became leader of the Chicago chapter, he organized weekly rallies, worked closely with the BPP's local People's Clinic, taught political education classes every morning at 6am, and launched a project for community supervision of the police. Hampton was also instrumental in the BPP's Free Breakfast Program. When Bob Brown left the Party with Stokely Carmichael, in the FBI-fomented SNCC/Panther split, Hampton assumed chairmanship of the Illinois state BPP. This automatically made him a national BPP deputy chairman. As the nationwide Panther leadership began to be decimated by the effects of the FBI's COINTELPRO, Hampton's prominence in the national hierarchy increased rapidly and dramatically. Eventually he was in line to be appointed to the Party's Central Committee's Chief of Staff. He would have achieved this position had he not been killed on December 4, 1969.[11][12]

FBI investigation

Hampton's effective leadership and talent for communication marked him as a major threat to the FBI. It began keeping close tabs on his activities. Investigations have shown that FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover was determined to prevent the formation of a cohesive Black movement in the United States. Hoover believed the Panthers, Young Patriots, Young Lords, and similar radical coalitions Hampton forged in Chicago were a stepping stone to the rise of a revolution that could threaten the U.S. government and society.

The FBI opened a file on Hampton in 1967. It tapped Hampton's mother's phone in February 1968 and by May placed Hampton on the Bureau's "Agitator Index" as a "key militant leader."[11] In late 1968, the Racial Matters squad of the FBI's Chicago field office recruited William O'Neal to work with it; he had recently been arrested twice for interstate car theft and impersonating a federal officer. In exchange for having his felony charges dropped and a monthly stipend, O'Neal agreed to infiltrate the BPP as a counterintelligence operative.[14]

O'Neal joined the Party and quickly rose in the organization, becoming Director of Chapter security and Hampton's bodyguard. In 1969, the FBI Special Agent in Charge (SAC) in San Francisco wrote Hoover that the agent's investigation had found that, in his city at least, the Panthers were primarily feeding breakfast to children. Hoover responded with a memo implying that the agent's career prospects depended on his supplying evidence to support Hoover's view that the BPP was "a violence-prone organization seeking to overthrow the Government by revolutionary means".[15]

By means of anonymous letters, the FBI sowed distrust and eventually instigated a split between the Panthers and the Rangers. O'Neal personally instigated an armed clash between them on April 2, 1969. The Panthers became effectively isolated from their power base in the Chicago ghetto, so the FBI worked to undermine its ties with other radical organizations. O'Neal was instructed to "create a rift" between the Party and Students for a Democratic Society, whose Chicago headquarters was blocks from the Panthers'. The Bureau released a batch of racist cartoons in the Panthers' name,[16] aimed at alienating white activists. It also launched a disinformation program to forestall formation of the Rainbow Coalition, but the BPP did make an alliance with the Young Patriots and Young Lords. In repeated directives, Hoover demanded that COINTELPRO personnel investigate the Rainbow Coalition, "destroy what the [BPP] stands for", and "eradicate its 'serve the people' programs".[17]

Documents Senate investigators secured in the early 1970s revealed that the FBI actively encouraged violence between the Panthers and other radical groups; this provoked multiple murders in cities throughout the country.[18] On July 16, 1969, an armed confrontation between party members and the Chicago Police Department resulted in one BPP member mortally wounded and six others arrested on serious charges.

In early October, Hampton and his girlfriend, Deborah Johnson (now known as Akua Njeri), pregnant with their first child (Fred Hampton Jr.), rented a four-and-a-half-room apartment at 2337 West Monroe Street to be closer to BPP headquarters. O'Neal reported to his superiors that much of the Panthers' "provocative" stockpile of arms was stored there and drew them a map of the apartment. In early November, Hampton traveled to California on a speaking engagement to the UCLA Law Students Association. While there, he met with the remaining BPP national hierarchy, who appointed him to the Party's Central Committee. He was soon to take the position of Chief of Staff and major spokesman.[19]

Death

Hampton had quickly risen in the Black Panther Party, and his talent as a political organizer was described as remarkable.[11][12] In 1968, he was on the verge of creating a merger between the BPP and a southside street gang with thousands of members, which would have doubled the size of the national BPP.[11][12]

In November 1969, Hampton traveled to California and met with the National BPP leadership at UCLA. They offered him a position on the Central Committee as the chief of staff and asked him to serve as the national spokesman for the BPP. While Hampton was out of town, two Chicago police officers, John J. Gilhooly and Frank G. Rappaport, were fatally shot in a gun battle with Panthers on the night of November 13; one died the next day.[20] A total of nine police officers were shot; 19-year-old Panther Spurgeon Winter Jr. was killed by police, and another Panther, Lawrence S. Bell, was charged with murder. In an unsigned editorial headlined "No Quarter for Wild Beasts", the Chicago Tribune urged that Chicago police officers approaching suspected Panthers "should be ordered to be ready to shoot."[21]

The FBI, determined to prevent any enhancement of the BPP leadership's effectiveness, decided to set up an arms raid on Hampton's Chicago apartment. Informant William O'Neal provided them with detailed information about Hampton's apartment, including the layout of furniture and the bed in which Hampton and his girlfriend slept. An augmented, 14-man team of the SAO (Special Prosecutions Unit) was organized for a pre-dawn raid; they were armed with a search warrant for illegal weapons.[11][12]

On the evening of December 3, Hampton taught a political education course at a local church, which was attended by most members. Afterward, as was typical, several Panthers went to his Monroe Street apartment to spend the night, including Hampton and Deborah Johnson, Blair Anderson, James Grady, Ronald "Doc" Satchell, Harold Bell, Verlina Brewer, Louis Truelock, Brenda Harris, and Mark Clark. There they were met by O'Neal, who had prepared a late dinner, which the group ate around midnight. O'Neal had slipped the barbiturate sleep agent secobarbitol into a drink that Hampton consumed during the dinner, in order to sedate Hampton so he would not awaken during the subsequent raid. O'Neal left at this point, and, at about 1:30 a.m., December 4, Hampton fell asleep mid-sentence talking to his mother on the telephone.[22][23][24][25] Although Hampton was not known to take drugs, Cook County chemist Eleanor Berman would report that she ran two separate tests which each showed evidence of barbiturates in Hampton's blood. An FBI chemist would later fail to find similar traces, but Berman stood by her findings.[26]

The raid was organized by the office of Cook County State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan, using officers attached to his office.[27] Hanrahan had recently been strongly criticized by Hampton, who said that Hanrahan's talk about a "war on gangs" was really rhetoric used to enable him to carry out a "war on black youth".[28]

At 4:00 a.m., the heavily armed police team arrived at the site, divided into two teams, eight for the front of the building and six for the rear. At 4:45 a.m., they stormed into the apartment. Mark Clark, sitting in the front room of the apartment with a shotgun in his lap, was on security duty. The police shot him in the chest, killing him instantly.[29] An alternative account said that Clark answered the door and police immediately shot him. Either way, Clark's gun discharged once into the ceiling.[30] This single round was fired when he suffered a reflexive death-convulsion after being shot. This was the only shot fired by the Panthers.[12][31][32]

Hampton, drugged by barbiturates, was sleeping on a mattress in the bedroom with his fiancée, Deborah Johnson, who was nine months pregnant with their child.[29] She was forcibly removed from the room by the police officers while Hampton still lay unconscious in bed.[33] Then, the raiding team fired at the head of the south bedroom. Hampton was wounded in the shoulder by the shooting.

Fellow Black Panther Harold Bell said that he heard the following exchange:

- "That's Fred Hampton."

- "Is he dead?... Bring him out."

- "He's barely alive."

- "He'll make it."[34]

The injured Panthers said they heard two shots. According to Hampton's supporters, the shots were fired point blank at Hampton's head.[35] According to Deborah Johnson, an officer then said:

- "He's good and dead now."[34]

Hampton's body was dragged into the doorway of the bedroom and left in a pool of blood. The officers directed their gunfire at the remaining Panthers who had been sleeping in the north bedroom (Satchel, Anderson, Brewer and Harris).[29] Verlina Brewer, Ronald "Doc" Satchel, Blair Anderson, and Brenda Harris were seriously wounded,[29] then beaten and dragged into the street. They were arrested on charges of aggravated assault and the attempted murder of the officers. They were each held on US$100,000 bail.[30]

In the early 1990s, Deborah Johnson was interviewed about the raid by Jose Cha Cha Jimenez, former president and co-founder of the Young Lords Organization. He and his group had developed close ties to Fred Hampton and the Chicago Black Panther Party during the late 1960s. She said:

- I believe Fred Hampton was drugged. The reason why is because when he woke up when the person [Truelock] said, "Chairman, chairman," he was shaking Fred's arm, you know, Fred's arm was folded across the head of the bed. And Fred—he just raised his head up real slow. It was like watching a slow motion. He raised. His eyes were open. He raised his head up real slow, you know, with his eyes toward the entranceway, toward the bedroom and laid his head back down. That was the only movement he made [...][33]

The seven Panthers who survived the raid were indicted by a grand jury on charges of attempted murder, armed violence, and various other weapons charges. These charges were subsequently dropped. During the trial, the Chicago Police Department claimed that the Panthers were the first to fire shots. But a later investigation found that the Chicago police fired between ninety and ninety-nine shots, while the only Panthers shot was a bullet that hit the ceiling from Mark Clark's fallen shotgun.[30][37]

After the raid, the apartment was left unguarded. The Panthers sent some members to investigate, accompanied by a videographer to document the scene. The footage was later released as part of the 1971 documentary The Murder of Fred Hampton. After a break-in at an FBI office in Pennsylvania, the existence of COINTELPRO, an illegal counter-intelligence program, was revealed and reported. With this program revealed, many activists and others began to suspect that the police raid and the shooting of Fred Hampton were conducted under this program. One of the documents released after the break-in was a floor plan of Hampton's apartment. Another document outlined a deal that the FBI brokered with the US deputy attorney general to conceal the FBI's role in the killing of Hampton and the existence of COINTELPRO.[37]

Aftermath

At a press conference the next day, the police announced the arrest team had been attacked by the "violent" and "extremely vicious" Panthers and had defended themselves accordingly. In a second press conference on December 8, the police leadership praised the assault team for their "remarkable restraint", "bravery", and "professional discipline" in not killing all the Panthers present. Photographic evidence was presented of "bullet holes" allegedly made by shots fired by the Panthers, but this was soon challenged by reporters. An internal investigation was undertaken, and the police claimed that their colleagues and friends on the assault team were exonerated of any wrongdoing.

Hampton's funeral was attended by 5,000 people, and he was eulogized by black leaders, such as Jesse Jackson and Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King's successor as head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In his eulogy, Jackson noted that "when Fred was shot in Chicago, black people in particular, and decent people in general, bled everywhere."[38] On December 6, members of the Weather Underground destroyed numerous police vehicles in a retaliatory bombing spree at 3600 N. Halsted Street, Chicago.[39]

The police described their raid on Hampton's apartment as a "shootout". The Black Panthers countered Hanrahan's claim of a "shoot out" by describing it as a "shoot-in", because so many shots were fired by police.[40][41]

On December 11 and 12, the two competing daily newspapers, the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Sun-Times, published vivid accounts of the events, but drew different conclusions. At that time, the Chicago Tribune was considered the politically conservative newspaper, and the Chicago Sun-Times was considered the politically liberal newspaper. On December 11, the Chicago Tribune published a page 1 article titled, "Exclusive – Hanrahan, Police Tell Panther Story." The article included photographs, supplied by Hanrahan's office, that depicted bullet holes in a thin white curtain and door jamb as evidence that the Panthers fired multiple bullets at the police.[42][43]

Jack Challem, editor of the Wright College News, the student newspaper at Wright Junior College in Chicago, had visited the apartment on Saturday, December 6, as it was unsecured. He took numerous photographs of the crime scenes. A member of the Black Panthers was allowing visitors to tour the apartment. Challem's photographs did not show the bullet holes as reported by the Chicago Tribune. On the morning of December 12, after the Chicago Tribune article had appeared with the Hanrahan-supplied photos, Challem contacted a reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times, showed him his own photographs, and encouraged the other reporter to visit the apartment. That evening, the Chicago Sun-Times published a page 1 article with the headline: "Those 'bullet holes' aren't." According to the article, the alleged bullet holes (supposedly the result of the Panthers shooting in the direction of the police) were nail heads.[44]

Four weeks after witnessing Hampton's death at the hands of the police, Deborah Johnson gave birth to their son Fred Hampton Jr.[45]

Civil rights activists Roy Wilkins and Ramsey Clark (styled as "The Commission of Inquiry into the Black Panthers and the Police") subsequently alleged that the Chicago police had killed Fred Hampton without justification or provocation and had violated the Panthers' constitutional rights against unreasonable search and seizure.[46] "The Commission" further alleged that the Chicago Police Department had imposed a summary punishment on the Panthers.[47]

A federal grand jury did not return any indictment against any of the numerous individuals involved with the planning or execution of the raid, including the officers involved in killing Hampton.[48] FBI informant William O'Neal, who had given the FBI the floor plan of the apartment and drugged Hampton, later admitted his involvement in setting up the raid. He committed suicide on January 25, 1990.[26][49]

Inquest

Shortly after the raid, Cook County coroner Andrew Toman began forming a special six-member coroner's jury to hold an inquest into the deaths of Hampton and Clark.[50] On December 23, Toman announced four additions to the jury, who included two African-American men: physician Theodore K. Lawless and attorney Julian B. Wilkins, the son of J. Ernest Wilkins, Sr.[50] He said the four were selected from a group of candidates submitted to his office by groups and individuals representing both Chicago's black and white communities.[50] Civil rights leaders and spokesmen for the black community were reported to have been disappointed with the selection.[51]

An official with the Chicago Urban League said: "I would have had more confidence in the jury if one of them had been a black man who has a rapport with the young and the grass roots in the community."[51] Gus Savage said that such a man to whom the community could relate need not be black.[51] The jury eventually included a third black man, who had been a member of the first coroner's jury sworn in on December 4.[3]

The blue-ribbon panel convened for the inquest on January 6, 1970. On January 21 they ruled the deaths of Hampton and Clark to be justifiable homicides.[3][52][53][54] The jury qualified their verdict on the death of Hampton as "based solely and exclusively on the evidence presented to this inquisition";[3] police and expert witnesses provided the only testimony during the inquest.[55] Jury foreman James T. Hicks stated that they could not consider the charges made by surviving Black Panthers who had been in the apartment; they had told reporters that the police entered the apartment shooting. The survivors were reported to have refused to testify during the inquest because they faced criminal charges of attempted murder and aggravated assault during the raid.[55] Attorneys for the Hampton and Clark families did not introduce any witnesses during the proceedings, but described the inquest as "a well-rehearsed theatrical performance designed to vindicate the police officers".[3] State's attorney Edward Hanrahan said the verdict was recognition "of the truthfulness of our police officers' account of the events".[3]

Federal grand jury

Released on May 15, 1970, the reports of a federal grand jury criticized the actions of the police, the surviving Black Panthers, and the Chicago news media.[56][57] The grand jury said that the police department's raid was "ill conceived" and that there were many errors committed during the post-raid investigation and reconstruction of the events. It said that the refusal of the surviving Black Panthers to cooperate hampered the investigation, and that the press "improperly and grossly exaggerated stories".[56][57]

1970 Civil rights lawsuit

In 1970, the survivors and relatives of Hampton and Clark filed a civil suit, stating that the civil rights of the Black Panther members were violated by the joint police/FBI raid and seeking $47.7 million in damages.[58] Twenty-eight defendants were named, including Assistant DA Hanrahan as well as the City of Chicago, Cook County, and federal governments.[58] It took years to get to trial, which lasted 18 months. It was reported to have been the longest federal trial up to that time.[58] After its conclusion in 1977, Judge Joseph Sam Perry of United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois dismissed the suit against 21 of the defendants prior to jury deliberations.[58] After jurors deadlocked on a verdict, Perry dismissed the suit against the remaining defendants .[58]

The plaintiffs appealed. In 1979, the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Chicago found that the government had withheld relevant documents, thereby obstructing the judicial process in this case.[58] Reinstating the case against 24 of the defendants, the Court of Appeals ordered a new trial.[58] The Supreme Court of the United States heard an appeal by defendants, but voted 5–3 in 1980 to return the case to the District Court for a new trial.[58]

In 1982, the City of Chicago, Cook County, and the federal government agreed to a settlement in which each would pay $616,333 to a group of nine plaintiffs, including the mothers of Hampton and Clark.[58] The $1.85 million settlement was believed to be the largest ever in a civil rights case.[58] G. Flint Taylor, one of the attorneys representing the plaintiffs, said: "The settlement is an admission of the conspiracy that existed between the F.B.I. and Hanrahan's men to murder Fred Hampton."[59] An Assistant United States Attorney, Robert Gruenberg, said that the settlement was intended to avoid another costly trial and it was not an admission of guilt or responsibility by any of the defendants.[59]

Controversy

The allegation that Hampton was assassinated has been debated since the day he and Clark were killed in the police raid.[60] Ten days afterward, Bobby Rush, then the deputy minister of defense for the Illinois Black Panther party, called the raiding party an "execution squad".[61] As is typical in settlements, the three government defendants did not acknowledge claims of responsibility for plaintiffs' allegations. Some commentators have debated whether the men died in an exchange of gunfire with police or were intentionally slain.[60] Several scholars and documentaries assert that Hampton's killing was a political assassination perpetrated by Chicago police with help from the FBI.

Michael Newton is among those writers who have concluded that Hampton was assassinated.[62] In his 2016 book Unsolved Civil Rights Murder Cases, 1934–1970, Newton writes that Hampton "was murdered in his sleep by Chicago police with FBI collusion."[63] This view is also presented in Jakobi Williams's book From the Bullet to the Ballot: The Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party and Racial Coalition Politics in Chicago.[64]

Legacy

Legal and political impacts

According to a 1969 Chicago Tribune report, "The raid ended the promising political career of Cook County State's Atty. Edward V. Hanrahan, who was indicted but cleared with 13 other law-enforcement agents on charges of obstructing justice. Bernard Carey, a Republican, defeated him in the next election, in part because of the support of outraged black voters."[65] The families of Hampton and Clark filed a US$47.7 million civil suit against the city, state, and federal governments. The case went to trial before Federal Judge J. Sam Perry. After more than 18 months of testimony and at the close of the Plaintiff's case, Judge Perry dismissed the case. The Plaintiffs appealed and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit reversed, ordering the case to be retried. More than a decade after the case had been filed, the suit was finally settled for $1.85 Million.[48] The two families each shared in the settlement.

Jeffrey Haas, who, together with his law partners G. Flint Taylor and Dennis Cunningham and attorney James D. Montgomery, were the attorneys for the plaintiffs in the federal suit Hampton v. Hanrahan, wrote a book about these events. He said that Chicago was worse off without Hampton:

Of course, there's also the legacy that, without a young leader, I think the West Side of Chicago degenerated a lot into drugs. And without leaders like Fred Hampton, I think the gangs and the drugs became much more prevalent on the West Side. He was an alternative to that. He talked about serving the community, talked about breakfast programs, educating the people, community control of police. So I think that that's unfortunately another legacy of Fred's murder.[41]

In 1990, the Chicago City Council unanimously passed a resolution, introduced by then-Alderman Madeline Haithcock, commemorating December 4, 2004, as "Fred Hampton Day in Chicago". The resolution read in part: "Fred Hampton, who was only 21 years old, made his mark in Chicago history not so much by his death as by the heroic efforts of his life and by his goals of empowering the most oppressed sector of Chicago's Black community, bringing people into political life through participation in their own freedom fighting organization."[66]

Monuments and streets

A public pool was named in his honor in his home town of Maywood, Illinois.[67] In March 2006, supporters of Hampton's charity work proposed the naming of a Chicago street in honor of the former Black Panther leader. Chicago's chapter of the Fraternal Order of Police opposed this effort.[68] On Saturday September 7, 2007, a bust of Hampton was erected outside the Fred Hampton Family Aquatic Center.[69]

Weather Underground reaction

Two days after the killings of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, on December 6, 1969, members of the Weathermen destroyed numerous police vehicles in a retaliatory bombing spree at 3600 N. Halsted Street in Chicago.[70] Following this, the group became increasingly ultra-radicalized. On May 21, 1970, the group issued a "Declaration of War" against the United States government, and used for the first time its new name, the "Weather Underground Organization". They adopted fake identities and decided to pursue covert activities only. These initially included preparations for a bombing of a U.S. military non-commissioned officers' dance at Fort Dix, New Jersey, in what Brian Flanagan said had been intended to be "the most horrific hit the United States government had ever suffered on its territory".[71]

We've known that our job is to lead white kids into armed revolution ... Kids know the lines are drawn: revolution is touching all of our lives. Tens of thousands have learned that protest and marches don't do it. Revolutionary violence is the only way.

Media and popular culture

In film

A 27-minute documentary entitled Death of a Black Panther: The Fred Hampton Story[73] was used as evidence in the civil suit.[74][75] The 2002 documentary The Weather Underground shows in detail the way that group was deeply influenced by Hampton and his death—as well as showing that Hampton had kept his distance from them for being what he called "adventuristic, masochistic and Custeristic".[76]

Much of the first half of "A Nation of Law?", Eyes on the Prize episode 12, chronicles the leadership and extrajudicial killing of Fred Hampton. The events of Hampton's rise to prominence, J. Edgar Hoover's targeting of him, and Hampton's subsequent death are also recounted with footage in the 2015 documentary The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution.

In the 1999 TV mini-series The 60s, Fred Hampton appears serving free breakfast with the BPP. David Alan Grier plays Hampton. [77]

Judas and the Black Messiah is an upcoming film about Hampton. The film stars Daniel Kaluuya as Hampton, it is directed and produced by Shaka King, from a screenplay by King and Will Berson, and a story by King, Berson, and Kenny and Keith Lucas. It is due to be released in 2021. [78]

In literature

Jeffrey Haas wrote an account of Hampton's death, entitled The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther (2009).[26] Stephen King refers to Hampton in the novel 11/22/63 (2012), where a character discusses the ripple effect of traveling back in time to prevent President John F. Kennedy's assassination, which the character postulates would give rise to a series of events that could prevent Fred Hampton's assassination as well.[79]

In music

Artists that have mentioned Hampton in their music include:

- "Nashville" star Ronee Blakley's solo LP, "Ronee Blakley" (1972), includes the lyrics "I want to be a part of Fred Hampton / I want to be a part of his purity / You've got to heal the wounds".[80]

- Spoon's "Loss Leaders", from the "Soft Effects" EP, says "Fred tried to change their ways 'til he got some bullet holes / now he lives in outer space".[81]

- Rage Against the Machine's "Down Rodeo" says: "They ain't gonna send us campin' like they did my man Fred Hampton".[82]

- Ramshackle Glory refers to Fred Hampton in "First Song, Part 2", followed by an explanation that "justice doesn't flow from police guns, I'm reminded of that all the time".[83]

- Jay-Z, who was born December 4, 1969, mentions Fred Hampton on "Murder to Excellence" on Watch The Throne in the lyric "I arrived on the day Fred Hampton died, real niggas just multiply".

- Dead Prez mentions Fred Hampton and Fred Hampton Jr in the song "Behind Enemy Lines" on "Let's Get Free". In the lyric "Her father's a political prisoner, Free Fred / Son of a Panther that the government shot dead ..."[84]

- Killer Mike mentions Fred Hampton in the song "Don't Die" on R.A.P. Music. In the song, Mike states "Wanna leave me dead on a mattress, Hampton".[85]

- Lecrae mentions Fred Hampton in the song "Gangland". He says: "What people don't understand is that a lot of the leaders died. Medgar Evers (has been shot), Bunchy Carter (has been shot), Fred Hampton (has been shot), MLK (has been shot in Memphis Tennessee). These youngsters didn't have any direction. No leaders to look up to..."

- Thievery Corporation uses a thirty-second sample of one of his television interviews ("We intend to defend ourselves") in Retaliation Suite, on their 2008 Radio Retaliation album.

- Rick Ross mentions Fred Hampton in his song Powers That Be on the album Rather You Than Me. In the song, he says "Fred Hampton was an angel may his name ring".

- Propagandhi mention Fred Hampton in the song "Today's Empires, Tomorrow's Ashes", in the line "No justice shines upon the cemetery plots marked Hampton, Weaver or Anna-Mae".[86]

- Kendrick Lamar mentions Fred Hampton in the song "HiiiPoWeR", in the line "Fred Hampton on your campus, You can't resist his HiiiPoWeR." [87]

- The 2017 album The Underside of Power by Algiers begins with a sample of a Fred Hampton speech.

- Gil Scott-Heron's "No Knock" from the 1972 album "Free Will" contains the line, "No-knocked on my brother Fred Hampton, bullet holes all over the place."

- Michael Kiwanuka in 2019 album Kiwanuka wrote "Hero" as an hommage to the young Black Panthers activist.

- On January 13, 2006 Ernest Dawkins Chicago 12 performed "A Black Op'era" with music and poetry dedicated to "Chairman Fred Hampton" at the Sons d'hiver Festival de Musiques in Paris. In 2007 the live performance recording from the festival was released as a CD.

See also

- Anna Mae Aquash, murdered Native American activist

References

- Haas, Jeffrey (2010). The Assassination of Fred Hampton. Lawrence Hill. p. 4. ISBN 9781569767092.

- Haas, Jeffrey (2010). The Assassination of Fred Hampton. Lawrence Hill. p. 111. ISBN 9781569767092.

- Dolan, Thomas J. (January 22, 1970). "Panther Inquest Backs Police" (PDF). Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago. p. 3. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- Rutberg, Susan (December 6, 2017). "Nothing but a Northern Lynching: The Death of Fred Hampton Revisited". Huffpost. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- Thamm, Natalie (April 7, 2019). "Murder or 'Justifiable Homicide'?: The Death of the Revolutionary Fred Hampton". STMU History Media. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- Stubblefield, Anna (May 31, 2018). Ethics Along the Color Line. Cornell University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9781501717703.

- Burrough, Bryan (2016). Days of Rage: America's Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence. Penguin Publishing Group. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9780143107972.

- Lee, William (December 3, 2019). "In 1969, Charismatic Black Panthers Leader Fred Hampton Was Killed in a Hail of Gunfire. 50 Years Later, the Fight Against Police Brutality Continues". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- "Fred Hampton". National Archives. August 25, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- Jones, Cornelius (October 23, 2013). Don't Call Me Black, Call Me American. books.google.com/. ISBN 9781105520020.

- Ward Churchill; Jim Vander Wall (1988). Agents of Repression: The FBI's Secret Wars Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement. p. 66. ISBN 0-89608-293-8.

- Rod Bush (2000). We Are Not What We Seem: Black Nationalism and Class Struggle in the American Century. NYU Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-8147-1318-1.

- Williams, Jakobi, "Fred Hampton to Barack Obama: The Illinois Black Panther Party, the Original Rainbow Coalition, and Racial Coalition Politics in Chicago". Paper presented at the 96th Annual Convention of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Richmond, VA, October 4, 2011.

- Iberia HAMPTON et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. Edward V. HANRAHAN et al., Defendants-Appellees, United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, September 12, 1979, page 1, paragraph 13, Law Resource

- FBI document, May 27, 1969, "Director FBI to SAC San Francisco", available at the FBI reading room.

- Feldman, Jay (2012). Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 275–276. ISBN 9780307388230.

- Ward Churchill, "To Disrupt, Discredit and Destroy", in Kathleen Cleaver and George Katsiaficas (eds), Liberation, Imagination and the Black Panther Party, p.84 and p. 87.

- Michael Newton. Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, p. 206. ISBN 1610692853

- "Fred Hampton". National Archives. August 25, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- "Second Cop in Gun Battle Dies, Wounded Describe Nightmare", Chicago Tribune, November 14, 1969, p. 1.

- "No Quarter for Wild Beasts", Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1969, p. 10.

- Bush, Rod (2000). We Are Not What We Seem: Black Nationalism and Class Struggle in the American Century. NYU Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-8147-1318-1.

- Berger, Dan (2006). Outlaws of America: the Weather Underground and the politics of solidarity. AK Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-904859-41-3.

- Ward Churchill; Jim Vander Wall (2002). The COINTELPRO Papers: Documents from the FBI's Secret Wars Against Dissent. South End Press. p. 358. ISBN 0-89608-648-8.

- Peter Dale Scott (1996). Deep Politics and the Death of JFK. Univ. of California Press. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-520-20519-2.

- Jeffrey Haas (2010). The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther. Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 92, 299, 353. ISBN 978-1-55652-765-4.

- Napoliatno, Jo. "Edward Hanrahan, Prosecutor Tied to '69 Panthers Raid, Dies at 88", The New York Times, June 11, 2009. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- Dan Berger (2009). The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther. Chicago Review Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-55652-765-4.

- "Hampton v. City Of Chicago, et al". IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS. January 4, 1978. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Nelson Jr, Stuart (January 23, 2015). The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (Documentary).

- Dan Berger (2009). The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther. Chicago Review Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-55652-765-4.

- Berger, Dan (2006), Outlaws of America: the Weather Underground and the politics of solidarity, AK Press, ISBN 978-1-904859-41-3, pp. 132–133.

- Interview by Jose "Cha-Cha" Jimenez, c. 1990, File Folder 10, Box 4, The Collection on the Young Lords, DePaul University Special Collections and Archives. url=https://libguides.depaul.edu/ld.php?content_id=10135864

- Ward Churchill; Jim Vander Wall (1988). Agents of Repression: The FBI's Secret Wars Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement. pp. 69–70. ISBN 0-89608-293-8. Churchill and Vander Wall cited court transcripts of Iberia Hampton, et al. vs. Plaintiffs-Appellants, v Edward V. Hanrahan, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Nos. 77-1968, 77-1210 and 77-1370) as the primary source for their account of the police raid. In particular, witnesses Harold Bell and Deborah Johnson testified to the comments by police.

- Williams, Jakobi (2013). From the Bullet to the Ballot: The Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party and Racial Coalition Politics in Chicago. UNC Press Books. p. 185. ISBN 9780807838167.

- Stubblefield, Anna (May 31, 2018). Ethics Along the Color Line. Cornell University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9781501717703.

- Bennett, Hans (2010). "The Black Panthers and the Assassination of Fred Hampton". Journal of Pan African Studies. 3 (6).

- Mantler, Gordon Keith (2013). Power to the Poor: Black-Brown Coalition and the Fight for Economic Justice, 1960–1974. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9780807838518.

- Weather Underground Anon. Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism. UK, Red Dragon Print Collective, c. 1970.

- Barbara Reynolds, "Five years later Hampton alive", Chicago Tribune, December 8, 1974.

- "The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther". Interview with Jeffrey Haas, Democracy Now! December 9, 2009.

- "“Exclusive – Hanrahan, Police Tell Panther Story", Chicago Tribune, December 11, 1969.

- "Panther Battle Scene", Chicago Tribune, December 11, 1969.

- Joseph Reilly, "At Hampton Apartment", Chicago Sun-Times, December 12, 1969.

- "Fred Hampton Jr. Speaks About the Assassination of His Father".

- Ryan, Yvonne (November 19, 2013). Roy Wilkins: The Quiet Revolutionary and the NAACP. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813143804.

- Wilkins, Roy and Ramsey Clark, chairmen. Search and Destroy: A Report by the Commission of Inquiry into the Black Panthers and the Police. New York: Metropolitan Applied Research Center, 1973, 249.

- "The Black Panthers and the Assassination of Fred Hampton". Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- Michael Ervin (January 25, 1990). "The Last Hours of William O'Neal (He was the informant who gave the FBI the floor plan of Fred Hampton's apartment. Last week he ran onto the Eisenhower Expressway and killed himself)". Chicago Reader.

- O'Brien, John (December 24, 1969). "For More Selected for Jury to Probe Panther Raid Deaths". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. section 1, p. 4. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- Siddon, Arthur (December 24, 1969). "Panther Inquest Jury Selections Questioned". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. section 1, p. 4. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- Haas, Jeffrey (2010). The Assassination of Fred Hampton. Lawrence Hill. p. 111. ISBN 9781569767092.

- Rutberg, Susan (December 6, 2017). "Nothing but a Northern Lynching: The Death of Fred Hampton Revisited". Huffpost. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- Thamm, Natalie (April 7, 2019). "Murder or 'Justifiable Homicide'?: The Death of the Revolutionary Fred Hampton". STMU History Media. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- "Illinois jury rules Black Panther deaths 'justifiable homicide'". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. United Press International. January 22, 1970. p. 12. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- Grossman, Ron (December 4, 2014). "Fatal Black Panther raid in Chicago set off sizable aftershocks". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- Graham, Fred P. (May 16, 1970). "US Jury Assails Police in Chicago on Pather Raid". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- Franklin, Tim; Crawford Jr., William B (November 2, 1982). "County OKs Panther Death Settlements". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- Sheppard Jr., Nathaniel (November 14, 1982). "Plaintiffs in Panther Suite 'Knew We Were Right'". The New York Times. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- Davis, Robert (November 16, 1990). "Some have 2nd thoughts on making Panther's day". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. section 2, pp. 1,6. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- Koziol, Ronald (December 14, 1969). "Panther Slayings Split the City Into 'Name Calling' Factions". Chicago Tribune. section 1, p. 7. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Michael Newton. Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, p. 205. ISBN 1610692853

- Newton, Michael (2016). Unsolved Civil Rights Murder Cases 1934–1970. McFarland & Company. p. 249. ISBN 978-0786498956.

- Williams, Jakobi (February 28, 2013). From the Bullet to the Ballot: The Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party and Racial Coalition Politics in Chicago. UNC Press Books. p. 10. ISBN 9781469608167.

- "The Black Panther Raid and the death of Fred Hampton". Chicago Tribune. December 4, 1969.

- Monica Moorehead (December 16, 2004). "CHICAGO: 'Fred Hampton Day' declared". Workers World.

- "Village of Maywood Parks and Recreation". Archived from the original on October 5, 2010. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- "Group Wants Street Named After Black Panther Fred Hampton-Protesters filled City Hall Today – Susan Murphy-Milano". Movingoutmovingon.bloghi.com. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- "Maywood street statue honor slain Panther leader Hampton". Itsabouttimebpp.com. September 9, 2007. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- Anonymous (Weather Underground). Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism. UK, Red Dragon Print Collective, 1970.

- "Ex-Weather Underground Member Kathy Boudin Granted Parole" Archived November 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Democracy Now! August 21, 2003.

- Weather Underground Declaration of a State of War

- Death of a Black Panther: The Fred Hampton Story

- "The Death of a Black Panther – The Fred Hampton Story, 1969–70", Inteldocu, July 31, 2011.

- "Edward Hanrahan", Panjury.

- "The Seeds of Terror". The New York Times. November 22, 1981. p. 4.

- The '60s (TV Mini-Series 1999) – IMDb, retrieved July 8, 2020

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt9784798/

- King 2012:62.

- "Ronee Blakley: Fred Hampton", Artist Direct.

- "Spoon – Loss Leaders". Genius. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ""Down Rodeo" lyrics". Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- "First Song, part 2 Lyrics". First Song, part 2. Ramshackle Glory. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- Lyrics to Dead Prez' "Behind Enemy Lines"

- "Killer Mike – Don't Die"

- "Lyrics: Today's Empires, Tomorrow's Ashes". propagandhi.com.

- "Lyrics: HiiiPoWeR". genius.com.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fred Hampton |

- "The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther" – video report by Democracy Now! December 4, 2009.

- The Murder of Fred Hampton on IMDb (A 1971 documentary film directed by Howard Alk)

- FBI files on Fred Hampton

- From COINTELPRO to the Shadow Government: As Fred Hampton Jr. Is Released From 9 Years of Prison, a Look Back at the Assassination of Fred Hampton. 36:48 real audio. Tape: Fred Hampton, Deborah Johnson. Guests: Fred Hampton Jr., Mutulu Olugabala, Rosa Clemente. Interviewer: Amy Goodman. Democracy Now!. Tuesday, March 5, 2002. Retrieved May 12, 2005.

- "Power Anywhere Where There's People" A Speech By Fred Hampton

- National Young Lords Brief notes on Young Lords origins

- The short film Death of a Black Panther: The Fred Hampton Story is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Grand Valley State University Oral History Collection