Dim sum

Dim sum (simplified Chinese: 点心; traditional Chinese: 點心; pinyin: diǎnxīn; Cantonese Yale: dímsām) is a Chinese cuisine of bite-sized portions served in small steamer baskets or on plates. Dim sum is generally considered Cantonese,[1][2][3] though other varieties exist. In Cantonese tradition, dishes are usually served with tea. Together, they form a full tea brunch or yum cha (饮茶; 飲茶; yǐn chá; 'drink tea'), a term used interchangeably with dim sum.[4][5] Dim sum are traditionally served as fully cooked, ready-to-serve dishes. Some Cantonese teahouses have servers push around carts of dim sum for diners to pick from.

Etymology

The original meaning of the term dim sum remains unclear and debated.[6]

Some references state that the term originated in the Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420).[7][8] According to one legend, to show soldiers gratitude after battles, a general had civilians make buns and cakes to send to the front lines. "Gratitude", or 點點心意; diǎn diǎn xīnyì, later shortened to 點心 (dim sum), came to represent dishes made in a similar fashion.

However, no historical text supports that legend. Some versions date the legend to the Southern Song dynasty (960–1279)[9][10] after the term's earliest attestation in the Book of Tang (唐書; Táng shū.[8] Written in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–979), the book uses dim sum as a verb instead: 「治妝未畢, 我未及餐, 爾且可點心」; "Zhì zhuāng wèi bì, wǒ wèi jí cān, ěr qiě kě diǎnxīn", or "I have not finished preparing myself and been ready for a proper meal, therefore you can treat yourself with some small snacks".[8] In this context, dim sum (點心; 'to lightly touch (your) heart'), means "to barely fill (your) stomach".[8]

Dim sum dishes are usually associated with yum cha (Chinese: 飲茶; Cantonese Yale: yám chàh; pinyin: yǐnchá; lit.: 'drink tea'), a Cantonese brunch tradition.[11][12]

History

The city Guangzhou experienced an increase in commercial travel in the 10th Century[13] and the travelers stopped at tea houses for frequent, small-portion meals with tea called yum cha, or "drink tea" meal.[13][14] Yum cha includes two related concepts:[15]

- 一盅兩件, which is literally “one cup, two pieces.” This refers to the custom of serving teahouse customers two pieces of delicately made food items, savory or sweet, to complement their tea.

- 點心, which is dim sum and literally “touch heart.” This is the term used to designate the small food items that accompanied the drinking of tea.

Teahouse owners eventually added various snacks, called dim sum, and this practice of having tea with dim sum eventually evolved into modern yum cha.[13][16] While at the tea houses, travelers selected their preferred snacks from carts.[13] Visitors to tea houses often socialized as they ate and businesspeople negotiated deals over dim sum.[13]

Cantonese dim sum culture developed rapidly during the latter half of the nineteenth century in Guangzhou.[17] Teahouse dining areas were typically located upstairs and initial dim sum fare included steamed buns.[17] Eventually, specialized dim sum restaurants opened for business and the variety and quality of dim sum dishes rapidly evolved.[17] Cantonese dim sum was originally based on local foods, such as the sweet roast pork known as char siu and fresh rice noodles.[17] As dim sum continued to develop, chefs introduced influences and traditions from other regions of China and this was a start to the wide variety of dim sum.[17] Chefs created a large range of dim sum that even today comprises the majority of a teahouse’s dim sum offerings.[17] Part of this development included reducing portion sizes of larger dishes originally from northern China, such as stuffed steamed buns, so that can they easily be incorporated into the dim sum menu.[17] The rapid growth in dim sum restaurants was partly because people found the preparation of dim sum dishes to be time-consuming and preferred the convenience of dining out and eating a large variety of baked, steamed, pan-fried, deep-fried, and braised foods.[17] Dim sum continued to develop and also spread southward to Hong Kong.[18]

Dim sum normally considered as Cantonese can include a range of additional influences.[17] Over thousands of years, as people in China migrated in search of different or better places to live, they brought the recipes of their favorite foods and continued to prepare and serve the dishes.[17] Many Han Chinese migrated south seeking warmer climates.[17] Settlements took shape in the Yangtze River Valley, the central highlands, and the coastal southeast, including Guangdong.[17] The influence of Suzhou and Hangzhou is found in vegetarian soy skin rolls and pearl meatballs. The dessert squares flavored with red dates or wolfberries are influences from Beijing desserts.[17] Savory dishes, such as pot stickers and steamed dumplings have Muslim influence due to people traveling from Central Asia across the Silk Roads and into Guangdong.[17] These are just a few examples of how a wide range of influences became incorporated into traditional Cantonese dim sum.[17]

By the end of 1860, foreign influences had also begun to influence Guangdong’s dim sum with culinary innovations, such as catsup, Worcestershire sauce, and curry included into some savory dishes.[17] Custard pies evolved into the miniature beloved classics found in every teahouse.[17] Additional dim sum dishes evolved from Indian samosas, mango puddings, and Mexican conchas (snow-topped buns).[17] Cantonese-style dim sum has an extremely broad range of flavors, textures, cooking styles, and ingredients.[17] As a result, there are more than a thousand different varieties of dim sum.[17]

During the 1920's in Guangzhou, the deluxe places to enjoy tea were the tea pavilions which had refined and expansive surroundings.[17] The customers were wealthy and the tea pavillion service and dim sum were of very high caliber.[17] Upon entering a tea pavillion, customers would inspect tea leaves to ensure their quality and to verify the water temperature.[17] Once satisfied, these guests were presented with a pencil and a booklet listing the available dim sum.[17] A waiter would then tear their orders out of the booklet so that the kitchen could pan-fry, steam, bake, or deep-fry these dishes on demand.[17] Customers dined upstairs in privacy and comfort.[17] Servers carefully balanced the dishes on their arms or arranged them on trays as they climbed up and down the stairs.[17] Eventually, dim sum carts were used to serve the steamers and plates.[17]

People with average incomes also enjoyed tea and dim sum.[17] Early every morning, customers visited inexpensive restaurants that offered filled steamed buns and hot tea.[17] During mid-morning, students and government employees ordered two or three kinds of dim sum and ate as they read their newspapers.[17] In the late morning, people working at small businesses visited restaurants for breakfast and to use the restaurant as a small office space.[17]

By the late 1930s, Guangzhou’s teahouse culture included four high-profile dim sum chefs, with signs at the front doors of their restaurants.[17] There was heavy competition among teahouses and as a result, new varieties of dim sum were invented almost daily, including dishes influenced by the tea pastries of Shanghai and Beijing, as well as the Western Hemisphere.[17] Many new fusion dishes were also created, including puddings, baked rolls, turnovers, custard tarts, and Malay steamed cakes.[17]

There were also significant increases in the variety of thin wrappers used in both sweet and savory items:[17]

"If we concentrate only on the changes and development in the variety of “wrappers,” the main types of dim sum wrappers during the 1920s included such things as raised (for filled buns), wheat starch, shao mai (i.e., egg dough), crystal bun, crispy batter, sticky rice, and boiled dumpling wrappers. By the 1930s, the varieties of wrappers commonly used by chefs included . . . puff pastry, Cantonese short pastry, [and so on, for a total of 23 types] that were prepared by pan-frying, deep-frying, steaming, baking, and roasting"[17][19]

In the late 1930's, some of the early U.S. newspaper references to dim sum began to appear.[20]

Cuisine

There are over one thousand dim sum dishes available[21][22] and they are usually eaten as breakfast or brunch.[23][24] Cantonese dim sum has a very broad range of flavors, textures, cooking styles, and ingredients.[22] Dim sum can be categorized into regular items, seasonal offerings, weekly specials, banquet dishes, holiday dishes, house signature dishes, travel-friendly, as well as foods for breakfast, lunch, and late night snacks.[22]

The portion size of dim sum is partly influened by the subtropical climate of the southeast quadrant of Guangdong.[22] The subtropical climate can result in decreased appetites[25] and people prefer eating scaled-down meals throughout the day rather than the customary three large meals.[22] Teahouses in Guangzhou served “three teas and two meals,” which included lunch and dinner, as well as breakfast, afternoon, and evening teas with dim sum.[22]

Many dim sum dishes are made of seafood, chopped meats, or vegetables wrapped in dough or thin wrappings and steamed, deep-fried, or pan-fried.[3][21][26] A traditional dim sum brunch includes various types of steamed buns, such as cha siu bao (a steamed bun filled with barbecue pork), rice or wheat dumplings, and rice noodle rolls that contain a range of ingredients, including beef, chicken, pork, prawns, and vegetarian options.[27][28] Many dim sum restaurants also offer plates of steamed green vegetables, stuffed eggplant, stuffed green peppers, roasted meats, congee, and other soups.[29] Dessert dim sum is also available and can be ordered at any time since there is not a set sequence for the meal.[30][31]

It is customary to order "family-style", sharing the small dishes consisting of three or four pieces of dim sum among all members of the dining party.[23][32][33][34] Small portion sizes allow people to try a wide variety of food.[24]

Dishes

Dim sum restaurants typically have a wide variety of dishes, usually several dozen.[35]

Dumplings

Shrimp dumpling (蝦餃)

Shrimp dumpling (蝦餃) Teochew dumpling (潮州粉粿)

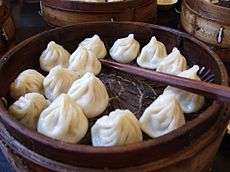

Teochew dumpling (潮州粉粿) Xiaolongbao (小笼包)

Xiaolongbao (小笼包)_(Pork_and_napa_cabbage).jpg) Guotie (鍋貼)

Guotie (鍋貼) Shaomai (燒賣)

Shaomai (燒賣) Taro dumpling (芋角)

Taro dumpling (芋角)

- Shrimp dumpling (蝦餃; xiā jiǎo; hā gáau): steamed dumpling with shrimp filling[36]

- Teochew dumpling (潮州粉粿; cháozhōu fěnguǒ; Chìu jāu fán gwó): steamed dumpling with peanuts, garlic, Chinese chives, pork, dried shrimp, and Chinese mushrooms.[37]

- Chive dumpling (韭菜餃): steamed dumpling with Chinese chives

- Xiaolongbao (小笼包; 小籠包; xiǎolóngbāo; síu lùhng bāau): dumplings containing a rich broth and filled with meat or seafood.[38][39]

- Guotie (鍋貼; guōtiē; wōtip): pan-fried dumpling, usually with meat and cabbage filling.[40][41]

- Shaomai (烧卖; 燒賣; shāomài; sīu máai): steamed dumplings with pork and prawns, usually topped off with crab roe and mushroom.[42]

- Taro dumpling (芋角; yù jiǎo; wuh gok): deep fried dumpling made with mashed taro and stuffed with diced mushrooms, shrimp and pork.[43]

- Haam Seui Gok (鹹水角; xiánshuǐ jiǎo; hàahm séui gok): deep fried dumpling with a slightly savoury filling of pork and chopped vegetables in a sweet and sticky wrapping.[44]

- Dumpling soup (灌湯餃; guàntāng jiǎo; guntōng gáau): soup with one or two big dumplings.

Rolls

Spring roll (春卷)

Spring roll (春卷) Tofu skin roll (腐皮捲)

Tofu skin roll (腐皮捲) Fresh bamboo roll (鮮竹卷)

Fresh bamboo roll (鮮竹卷) Barbecued pork rice roll (叉燒腸)

Barbecued pork rice roll (叉燒腸)- Rice noodle roll (腸粉)

Zhaliang (炸兩)

Zhaliang (炸兩)

- Spring roll (春卷; 春捲; chūnjuǎn; chēun gyún): a deep fried roll with various sliced vegetables (such as carrots, cabbage, mushroom and wood ear fungus) and sometimes meat.[45]

- Tofu skin roll (腐皮捲; fǔpíjuǎn; fuh pèih gyún): a roll made of tofu skin filled with various meat and sliced vegetables.[46]

- Fresh bamboo roll (鮮竹卷): a roll made of tofu skin filled with minced pork and bamboo shoot, typically served in an oyster sauce broth

- Four-treasure chicken roll (四寶雞扎): a roll made of tofu skin filled with chicken, Jinhua ham, fish maw (花膠), and Chinese mushroom

- Rice noodle roll (腸粉; chángfěn; chéungfán): steamed rice noodles with or without meat or vegetable filling. Popular fillings include beef, dough fritter, shrimp, and barbecued pork. Often served with a sweetened soy sauce.[47][48]

- Zhaliang (炸兩; jaléung): steamed rice noodles rolled around youjagwai (油炸鬼), typically doused in soy sauce, hoisin sauce, or sesame paste and sprinkled with sesame seeds.[49]

Bun

Barbecued pork bun (叉燒餐包)

Barbecued pork bun (叉燒餐包) Barbecued pork bun (叉燒包)

Barbecued pork bun (叉燒包) Sweet cream bun (奶黃包)

Sweet cream bun (奶黃包) Lotus paste bun (蓮蓉包) made to resemble roosters for Lunar New Year

Lotus paste bun (蓮蓉包) made to resemble roosters for Lunar New Year Pineapple buns (菠蘿包)

Pineapple buns (菠蘿包)

- Barbecued pork bun (叉燒包; chāshāo bāo; chāsīu bāau): buns with barbecued pork filling steamed to be white and fluffy.叉燒餐包; chāshāo cān bāo; chāsīu chāan bāau is a variant glazed and baked for a golden appearance.[50]

- Sweet cream bun (奶黃包; nǎihuáng bāo; náaih wòhng bāau): steamed buns with milk custard filling

- Lotus paste bun (蓮蓉包): steamed buns with lotus seed paste filling

- Pineapple bun (菠蘿包; bōluó bāo; bōlòh bāau): a usually sweet bread roll that does not contain pineapple but has a topping textured like pineapple skin.[51]

Cake

Turnip cake (蘿蔔糕)

Turnip cake (蘿蔔糕) Taro cake (芋頭糕;)

Taro cake (芋頭糕;) Water chestnut cake (馬蹄糕)

Water chestnut cake (馬蹄糕)

- Turnip cake (蘿蔔糕; luóbo gāo; lòh baahk gōu): pudding made from a mix of shredded white radish, bits of dried shrimp, Chinese sausage, and mushroom that is steamed, sliced, and pan-fried.[52][53]

- Taro cake (芋頭糕; yùtou gāo; wuh táu gōu): pudding made of taro.[54]

- Water chestnut cake (馬蹄糕; mǎtí gāo; máh tàih gōu): pudding made of crispy water chestnut; some restaurants also serve a variation made with bamboo juice.[55]

Meat

.jpg) Phoenix claws (鳳爪)

Phoenix claws (鳳爪)- Steamed meatball (山竹牛肉丸)

Spare ribs (排骨)

Spare ribs (排骨) Beef entrails (牛什; 牛雜)

Beef entrails (牛什; 牛雜) Siu mei (烧味; 燒味)

Siu mei (烧味; 燒味)

- Steamed meatball (山竹牛肉丸; niúròu wán; ngàuh yuhk yún): steamed meatballs served on thin tofu skin.[56]

- Phoenix claws (鳳爪; fèngzhuǎ; fuhng jáau): deep fried, boiled, and then steamed chicken feet with douchi. "White Cloud Phoenix Claws" (白雲鳳爪; báiyún fèngzhuǎ; baahk wàhn fuhng jáau) is a plain steamed version.[57][58]

- Spare ribs (排骨; páigǔ; pàaih gwāt): steamed pork spare ribs with douchi and sometimes garlic and chili

- Pork rinds and radish (豬皮蘿蔔): boiled and steamed pork rind and radish

- Pork blood (豬紅): stir-fried pork blood with douchi and scallion

- Beef tendon (牛筋)

- Reticulum beef tripe (金錢肚)

- Omasum beef tripe (牛百頁; 牛柏葉)

- Beef entrails (牛什; 牛雜): pieces of beef entrails such as tripe, pancreas, intestine, spleen, and lung served in a bowl of master stock

- Siu mei (烧味; 燒味; shāowèi; sīuméi): Hong Kong-style barbecue meat roasted in an oven. Popular varieties include char siu (Chinese: 叉燒), siu ngo (Chinese: 燒鵝), siu aap (Chinese: 燒鴨), white cut chicken (Chinese: 白切雞), soy sauce chicken (Chinese: 豉油雞), and siu yuk (Chinese: 燒肉).[59]

- Chicken wing (Chinese: 雞翼): deep fried (Chinese: 炸雞翼) or marinated in soy sauce and spices (Chinese: 瑞士雞翼)

Seafood

Deep fried squid (炸鱿鱼须)

Deep fried squid (炸鱿鱼须)

- Deep fried squid (炸鱿鱼须; 炸魷魚鬚; zhàyóuyúxū; ja yàuh yùh sōu): similar to fried calamari, the battered squid is deep-fried.

- Curry squid (咖哩鱿鱼; 咖哩魷魚): squid served in curry broth

Vegetable

- Steamed vegetables (油菜; yóucài; yáu choi): served with oyster sauce, popular varieties include lettuce (生菜; shēngcài; sāang choi), choy sum (菜心; càixīn; choi sām), gai lan (芥兰; 芥蘭; jièlán; gaailàahn) or water spinach (蕹菜; wèngcài; ung choi).

- Fried tofu (炸豆腐): deep fried tofu with salt and pepper

Rice

Lotus leaf rice (糯米雞)

Lotus leaf rice (糯米雞) Chinese sticky rice (糯米飯)

Chinese sticky rice (糯米飯)

- Lotus leaf rice (糯米雞; nuòmǐ jī; noh máih gāi): glutinous rice wrapped in a lotus leaf that typically contains egg yolk, dried scallop, mushroom, and meat (usually pork and chicken). A lighter variant is known as "pearl chicken" (珍珠雞; zhēnzhū jī; jānjyū gāi).[60]

- Chinese sticky rice (糯米飯; nuòmǐ fàn; noh máih faahn): stir fried (or steamed) glutinous rice with savoury Chinese sausage, soy sauce steeped mushrooms, sweet spring onions, and sometimes chicken marinated with a mixture of spices including five-spice powder.[61][62][63]

- Congee (粥; zhōu; jūk): many kinds of rice porridge, such as the "Preserved Egg and Pork Porridge" (皮蛋瘦肉粥; pídàn shòuròu zhōu; pèihdáan sauyuhk jūk).[64]

Dessert

Egg custard tarts (蛋撻)

Egg custard tarts (蛋撻) Tofu pudding (豆腐花)

Tofu pudding (豆腐花) Sesame ball (煎堆)

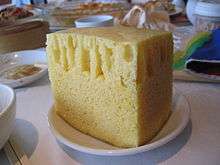

Sesame ball (煎堆) Malay sponge cake (馬拉糕)

Malay sponge cake (馬拉糕) Coconut pudding (椰汁糕)

Coconut pudding (椰汁糕)- Mango pudding (芒果布甸)

.jpg) Ox-tongue pastry (牛脷酥)

Ox-tongue pastry (牛脷酥)

- Egg tart (Chinese: 蛋撻; pinyin: dàntǎ; Cantonese Yale: daahn tāat): baked tart with egg custard filling.[65][66][67][68]

- Tofu pudding (豆腐花; dòufuhuā; dauh fuh fā): soft tofu served with a sweet ginger or jasmine flavoured syrup.[69][70]

- Sesame ball (煎堆; jiānduī; jīn dēui): deep fried chewy dough with various fillings (lotus seed, black bean, red bean pastes) coated in sesame seeds.[71][72]

- Thousand-layer cake (千層糕; qiāncéng gāo; chīnchàhng gōu): a dessert made of many layers of sweet egg dough

- Malay sponge cake (馬拉糕; mǎlā gāo; máhlāai gōu): steamed sponge cake flavoured with molasses.[73]

- White sugar sponge cake:(白糖糕; báitáng gāo; baahk tòng gōu): steamed sponge cake made with white sugar.[74][75]

- Coconut pudding (椰汁糕; yēzhī gāo; yèh jāp gōu): light and spongy but creamy coconut milk pudding made with a thin clear jelly layer made with coconut water on top.[76]

- Mango pudding (芒果布甸; mángguǒ bùdiàn; mōnggwó boudīn): a sweet, rich mango-flavoured pudding usually with large chunks of fresh mango and often served with a topping of evaporated milk.[77][78]

- Ox-tongue pastry (牛脷酥): a fried oval-shaped dough resembling an ox tongue that is similar to youjagwai, but sugar is added to the flour.[79]

- Tong sui (糖水): sweet dessert soups; popular varieties include black sesame soup (芝麻糊), red bean soup (红豆汤; 紅豆沙), mung bean soup (绿豆汤; 綠豆沙), sai mai lo (西米露), guilinggao (龟苓膏; 龜苓膏), peanut paste soup (花生糊), and walnut soup (核桃糊).[80]

Tea

The drinking of tea matters just as much as the food does.[2][81] Teas served during dim sum include:

- Chrysanthemum tea: instead of tea leaves, it is a flower-based tisane made from flowers of the species Chrysanthemum morifolium or Chrysanthemum indicum, which are most popular in East Asia.[82] To prepare the tea, chrysanthemum flowers (usually dried) are steeped in hot water (usually 90 to 95 °C (194 to 203 °F) after cooling from a boil) in a teapot, cup, or glass. A common mix with pu-erh is called guk pou (Chinese: 菊普; pinyin: jú pǔ; Cantonese Yale: gūk póu), a portmanteau of its component teas.

- Green tea: freshly picked leaves that go through heating and drying processes but not oxidation keep their original green color and chemical compounds, like polyphenols and chlorophyll.[83] Produced all over China and the most popular category of tea, green teas include the representative Dragon Well (Chinese: 龍井; pinyin: lóngjǐng; Cantonese Yale: lùhngjéng) and Biluochun from Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces, respectively.

- Oolong tea: partially oxidizing the tea leaves imparts them with characteristics of both green and black teas.[84][85][86] Oolongs taste more like green than black tea but have a less "grassy" flavour than the former. Major oolong-tea producing areas line the southeast coast of China, such as Fujian, Guangdong, and Taiwan. Tieguanyin (Chinese: 鐵觀音; pinyin: tiěguānyīn; Cantonese Yale: titgūnyām), one of the most popular, originated in Fujian province and is a premium variety with a delightful fragrance.

- Pounei (Cantonese) or pu-erh tea (Mandarin): usually a compressed tea, pu-erh has a unique earthy flavour from years of fermentation.[87][88]

- Scented teas: various mixes of flowers with green, black, or oolong teas exist. Flowers used include jasmine, gardenia, magnolia, grapefruit flower, sweet-scented osmanthus, and rose. Strict rules govern the proportion of flowers to tea. Jasmine tea, the most popular scented tea, is the one most often served at yum cha establishments.

The tea service includes several customs.[89][90][91][92] Typically, the server starts by asking diners what tea to serve. According to etiquette, the person closest to the tea pot pours tea for the others. Those served tea express thanks by tapping their first two fingers on the table.[33][92] Diners flip open the lid (of hinged metal tea pots) or offset the tea pot cover (on ceramic tea pots) to signal an empty pot.[92] Servers then refill the pot.

Restaurants

Many Cantonese restaurants start serving dim sum as early as five in the morning[93][94][95], while more traditional restaurants typically serve dim sum until mid-afternoon.[93][23][24] It has become commonplace for restaurants to serve dim sum at dinner time and even to sell various dim sum items a la carte for take-out.[96]

Dim sum has a unique serving method.[97] In dim sum restaurants or teahouses, servers offer dishes to customers from steam-heated carts.[21][97][98] Diners often prefer tables nearest the kitchen since servers and carts pass by these tables first.[34][95] Many restaurants place lazy susans on tables to help diners reach food and tea.[99]

Pricing of dishes at these types of restaurants may vary, but traditionally, the dishes are classified as "small", "medium", "large", "extra-large", or "special".[95][30] For example, a basket of dumplings may be considered a small dish, while a bowl of congee or plate of lo mai gai a large one. Dishes are then priced by size. Servers record orders with a rubber stamp or ink pen onto a bill card that remains on the table.[89][27][3] Servers in some restaurants use distinctive stamps to track sales statistics for each server. Menu items not typically considered dim sum fare, such as a plate of chow mein, are typically branded as "kitchen" dishes on menus and individually priced. When done eating, the customers simply call the servers over, and the bill is calculated based on the number of stamps or quantities marked in each priced section.

Another way of pricing the food consumed uses the number and color of the dishes left on the patron's table as a guide, much like the method used in some Japanese conveyor belt sushi restaurants. Some newer restaurants offer a "conveyor belt dim sum" format.[100]

Other Chinese restaurants may instead take orders from a pre-printed sheet of paper and serve à la carte, much like Spanish tapas restaurants,[101][102] to provide fresh, cooked-to-order dim sum or due to real estate and resource constraints.[103][104]

Fast food

Instant dim sum as a fast food has come into the market in Hong Kong,[105] mainland China,[106] Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, and Malaysia. People can enjoy snacks after defrosting or reheating instant dim sum in a microwave for three minutes.[105]

In many cities, vendors sell "street dim sum" from mobile carts. It usually consists of dumplings or meatballs steamed in a large container and served on a bamboo skewer. The customer can dip the whole skewer into a sauce bowl and then eat while standing or walking.

Dim sum can often be purchased from grocery stores in major cities.[89] These dim sum can be easily cooked by steaming, frying, or microwaving.[107][108] Major grocery stores in Hong Kong, Vietnam, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Mainland China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Thailand, Australia, United States, and Canada have a variety of frozen or fresh dim sum stocked at the shelves. These include dumplings, shaomai, baozi, rice noodle roll, turnip cake and steamed spare ribs.

In Hong Kong and other cities in Asia, dim sum can be purchased from convenience stores, coffee shops and other eateries.[109][110] Halal-certified dim sum that uses chicken instead of pork very popular in Hong Kong,[111] Malaysia,[112] Indonesia[113] and Brunei.[114]

Modern dim sum

In addition to traditional dim sum, some chefs also create and prepare new fusion-based dim sum dishes.[115][116][117][118] Variations designed for visual appeal on social media, such as dumplings and buns made to resemble animals, also exist.[119] Dim sum chefs have used cocoa power as coloring to create steamed bread puffs that appear like forest mushrooms, espresso powder as coloring and flavor for deep-fried riblets, pastry cream, and French puffs in order to create innovative dishes while honoring the history of dim sum.[17]

See also

- Cantonese cuisine

- Chinese cuisine

- Dim sim, Australian dumpling inspired by dim sum, with origins in local Cantonese restaurants.

- Hong Kong cuisine

- List of brunch foods

- List of dumplings

References

- Fallon, Stephen; Harper, Damian (2002). Hong Kong & Macau (10th ed.). Melbourne, Vic.: Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-86450-230-4. OCLC 48153757.

- "Fare of the Country; Why Dim Sum Is 'Heart's Delight'". The New York Times. 25 October 1981. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "What Is Dim Sum? The Beginner's Guide to South China's Traditional Brunch Meal". Asia Society. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Wong, Adele (1 November 2016). Hong Kong Food & Culture: From Dim Sum to Dried Abalone. Man Mo Media. ISBN 9887756008.

- "Dim Sum: A tradition that's anything but dim". South China Morning Post. 13 April 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "點心點解叫「點心」?". Bastille Post (in Chinese). 2016.

- 施, 莉雅 (2013). 精選美食王 (in Chinese). 萬里.

- 蘇, 建新 (2011). 人人都要學的三分鐘國文課5: 常用詞語篇 (in Chinese). 如果出版社.

- 劉, 利生 (2015). 影響世界的中國元素 - 中華美食. 元華文創.

- "吃「點心」與「閉門羹」的典故". 每日頭條. 2018.

- "Yum Cha – Cantonese Tea Brunch Tradition". www.travelchinaguide.com. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Gao, Sally. "6 Things You Should Know Before Eating Dim Sum In Hong Kong". Culture Trip. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Tribune, Leslie Gourse, Special to The. "DIM SUM HAS COME A LONG WAY, FROM ESOTERIC TO MASS POPULARITY". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "Fare of the Country; Why Dim Sum Is 'Heart's Delight'". The New York Times. 25 October 1981. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Jian Dui -- Sesame Balls (煎堆)". Kindred Kitchen. 13 May 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Parkinson, Rhonda (3 September 2019). "Delicious Dim Sum – Chinese Brunch". About.com-Chinese Food. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- Phillips, Carolyn (1 February 2017). "Modern Chinese History as Reflected in a Teahouse Mirror". Gastronomica. 17 (1): 56–65. doi:10.1525/gfc.2017.17.1.56. ISSN 1529-3262.

- Tam, S. (1997). Eating Metropolitaneity: Hong Kong Identity in yumcha. Australian Journal of Anthropology, 8(1), 291-306

- Feng, Mingquan (1986). "A discussion on Guangzhou's teahouse industry]. Guangzhou wenshi ziliao 廣州文史資料". Literary and historical materials on Guangzhou. 36, 1.

- Auffrey, Richard (6 March 2020). "The Passionate Foodie: Blob Joints: A History of Dim Sum in the U.S." The Passionate Foodie. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Simoons, Frederick J. (1991). Food in China : a cultural and historical inquiry. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-8804-X. OCLC 20392910.

- Phillips, Carolyn (1 February 2017). "Modern Chinese History as Reflected in a Teahouse Mirror". Gastronomica. 17 (1): 56–65. doi:10.1525/gfc.2017.17.1.56. ISSN 1529-3262.

- "How to Order Dim Sum, According to the Head Chef of the First Chinese Restaurant in North America to Receive a Michelin Star". Time. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Dim Sum". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "How the hot weather impacts your appetite". krem.com. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "The best thing you're not ordering at a dim sum restaurant". The Takeout. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Your Complete Guide to Dim Sum, the Traditional Chinese Brunch". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "The Ultimate Dim Sum Menu Guide". Dim Sum Central. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Your Ultimate Guide to a Typical Chinese Dim Sum Menu". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Everything You Need to Know About Dim Sum". Spoon University. 31 December 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Dim Sum Etiquette - Chinese/Lunar New Year | Epicurious.com". Epicurious. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- "Dim Sum". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Millson, Alex (6 December 2017). "Six Rules for Eating Dim Sum Like a Pro: A top chef in Hong Kong tells all". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Dim Sum Etiquette - Chinese/Lunar New Year". Epicurious. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- TODAY, Larry Olmsted, special for USA. "Great American Bites: Ping's serves savory dim sum in NYC's Chinatown". USA TODAY. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Albala, Ken (2011). Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia. 3. ABC-CLIO. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-313-37626-9 – via Google Books.

- Stone, A. (2009). Hong Kong. Con Cartina. Ediz. Inglese. Best Of Series. Lonely Planet. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-74220-514-4. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- 古時面皮中有餡之物方稱爲饅頭。見曾维华,〈古代的馒头〉,《上海师范大学学报(哲学社会科学版)》1995年第2期,页157。

- 古時面皮中有餡之物方稱爲饅頭。見曾维华,〈古代的馒头〉,《上海师范大学学报(哲学社会科学版)》1995年第2期,页157。

- Fong, Nathan (5 February 2013). "Potstickers: A tasty traditional dish for Lunar New Year". The Vancouver Sun.

- Parkinson, Rhonda Lauret (2003). The Everything Chinese Cookbook: From Wonton Soup to Sweet and Sour Chicken. Simon & Schuster Canada, Inc.

- Hsiung, Deh-Ta. Simonds, Nina. Lowe, Jason. [2005] (2005). The food of China: a journey for food lovers. Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-681-02584-4. p 38.

- "蜂巢炸芋角". chinabaike.com. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "Guide to Authentic Dim Sum Dishes for Yum Cha & Zao Cha | Welcome To China". welcometochina.com.au. 6 November 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- yeinjee (23 January 2008). "Maxim's Chinese Restaurant, Hong Kong International Airport". yeinjee.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Hsiung, Deh-Ta. Simonds, Nina. Lowe, Jason. [2005] (2005). The food of China: a journey for food lovers. Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-681-02584-4. p35.

- "晶莹剔透,香滑可口--肠粉". 美食天下 (in Chinese). Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- "的確涼布 拉出完美腸粉". Apple Daily (in Chinese). 17 August 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- "Gallery: The Serious Eats Guide to Dim Sum: Serious Eats". Derious Eats. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Hsiung, Deh-Ta. Simonds, Nina. Lowe, Jason. [2005]. The Food of China: A Journey for Food Lovers. Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-681-02584-4. p. 24.

- "Hong Kong food: 40 dishes we can't live without - 6. 'Pineapple' bun". CNN Travel. 13 July 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Bartholomew, Ian (24 January 2008). "New Year's Eve dinner: easy as pie". Taipei Times. p. 13. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- "Turnip or Radish Cake with Chinese Sausages". tastehongkong.com. 23 February 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "Chinese New Year Taro Cake". christinesrecipes.com. 26 January 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "Water Chestnut Cake for Chinese New Year and sometimes Valentine's Day". tastehongkong.com. 10 February 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- "Nutrient Values of Chinese Dim Sum" (PDF). Food and Environmental Hygiene Department. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Christopher DeWolf; Izzy Ozawa; Tiffany Lam; Virginia Lau; Zoe Li (13 July 2010). "40 Hong Kong foods we can't live without". CNN Go. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Shimabukuro, Betty. "Dive In, Feet First", Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 11 November 1998.

- Zoe Li (29 August 2011). "Hong Kongers eat 66,000 tons of siu mei a year". CNN Go. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- Hsiung, Deh-Ta. Simonds, Nina. Lowe, Jason. [2005] (2005). The food of China: a journey for food lovers. Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-681-02584-4. p27.

- Betty (8 January 2015). "No Mi Fan (糯米饭 ) without a steamer (Chinese Sticky Rice)". Food52. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Jennifer Che (1 September 2001). "Chinese Sticky Rice (Nuo Mi Fan)". Tiny Urban Kitchen. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Nado2003 (7 January 2008). "Chinese Sticky Rice Nuomi Fan) Recipe". Food.com. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- (家政), 陳春香 (1 April 2006). Congee - Special Porridge (Chinese Edition). ISBN 978-9868213630.

- "除了奶茶,還有蛋撻 - 香港文匯報". paper.wenweipo.com. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "Hong Kong egg tarts are not vegetarian – and here's why". South China Morning Post. 13 December 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- "澳門蛋撻的背後:夫妻離婚,肯德基爺爺竟成最大贏家!" (in Chinese). Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- Gao, Sally. "Everything You Need To Know About The Hong Kong Egg Tart". Culture Trip. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- 教育部簡編國語辭典修訂本.

【豆腐】 注音 ㄉㄡˋ ㄈㄨˇ 漢語拼音 dòu fǔ

- Mary Bai (19 October 2011). "Tofu, a Healthy Traditional Food in China". China International Travel Service Limited. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- Misty, Littlewood and Mark Littlewood, 2008 Gateways to Beijing: a travel guide to Beijing ISBN 981-4222-12-7, pp. 52.

- "Sesame Balls". Ching He Huang. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- Ting, Chew-Peh (1982). Chinese Immigration and the Growth of a Plural Society in Peninsular Malaysia. United States: Research in Race and Ethnic Relations. pp. 103–123.

- Shimabukuro, Bitty (21 May 2003). "Rice cake revelation". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- 梅联华 (2008). 南昌民俗 (in Chinese). 江西人民出版社. ISBN 9787210038184.

- What is a coconut bar? Wisegeek.com. Accessed 31 March 2012.

- Olver, Lynne (10 March 2012). "puddings, custards & creams". The Food Timeline. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Andrew Dembina (26 August 2010). "8 bone-chilling summer desserts for Hong Kong". CNN Go. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Johnny Law (20 January 2011). "簡單粥品又一餐". Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- So Good Blog. "Hong Kong: the Sugar Land of Sweet Soup (Tong Sui)." Wenna Pang. Retrieved 2017-06-07.

- Stevenson, Rachel (15 February 2018). "The Ideal Tea Pairing with Dim Sum Guide". Ideal Magazine. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Campbell, Dawn L. (1995). The tea book. Gretna: Pelican Publishing. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-56554-074-3.

- Khan N, Mukhtar H (2013). "Tea and health: studies in humans". Current Pharmaceutical Design (Literature Review). 19 (34): 6141–7. doi:10.2174/1381612811319340008. PMC 4055352. PMID 23448443.

- Zhongguo Chajing pp. 222–234, 271–282, 419–412, chief editor: Chen Zhongmao, publisher: Shanghai Wenhua Chubanshe (Shanghai Cultural Publishers) 1991.

- 施海根,中國名茶圖譜、烏龍茶黑茶及壓製茶花茶特種茶卷 p2,上海文化出版社 2007 ISBN 7-80740-130-3

- Joseph Needham, Science and Civilization in China, vol. 6, Cambridge University Press, 2000, part V, (f) Tea Processing and Use, pp. 535–550 "Origin and processing of oolong tea".

- Yoder, Austin (13 May 2013). "Pu'er Vs. Pu-erh: What's the Deal with the Different Spellings?". Tearroir. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016.

- Chen ZM (1991), p. 438, chpt. "Manufacturing pu'er [普洱茶的制造]"

- "Entertaining from ancient Rome to the Super Bowl: an encyclopedia". Choice Reviews Online. 46 (08): 46–4201-46-4201. 1 April 2009. doi:10.5860/choice.46-4201. ISSN 0009-4978.

- "The Serious Eats Guide to Dim Sum". Serious Eats. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Chinese food lovers' guide to ordering, eating and appreciating dim sum". Dallas News. 25 January 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Chiang, Karen. "The yum cha rules you need to know". BBC. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Jacobs, Harrison. "Here's how to navigate one of the most epic New York food traditions — 'Dim Sum' in Chinatown". Business Insider. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- 梁廣福. (2015). 再會茶樓歲月 (初版. ed.). 香港: 中華書局(香港)有限公司

- "What is Dim Sum?". Dim Sum Central. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Scholem, Richard Jay (16 August 1992). "A la Carte; Dim Sum Delights". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Phillips, C. (2016). The Dim Sum Field Guide: A Taxonomy of Dumplings, Buns, Meats, Sweets, and Other Specialties of the Chinese Teahouse. Ten Speed Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-60774-956-1. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Guides, R. (2010). The Rough Guide to Southeast Asia On A Budget. Rough Guides. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-4053-8686-9. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Daniel A. Gross. "The Lazy Susan, the Classic Centerpiece of Chinese Restaurants, Is Neither Classic nor Chinese". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Corporation, Ready-Market Online. "Dim Sum restaurant Solution Project". Hong Chiang Technology Industry Co. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- James, Trevor (9 August 2019). "What is Dim Sum + The Ultimate Ordering Guide". The Food Ranger. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Six rules for eating dim sum like a pro". South China Morning Post. 10 December 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Embiricos, George (16 June 2015). "Dim Sum Has Gotten The Hell Out Of Chinatown". Food Republic. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Britain's Dim Sum Trolleys Are Making Their Last Rounds". Vice. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Wu, D.Y.H.; Tan, C.B. (2001). Changing Chinese Foodways in Asia. Academic monograph on Chinese food culture. Chinese University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-962-201-914-0. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Ball, S.; Horner, S.; Nield, K. (2009). Contemporary Hospitality and Tourism Management Issues in China and India. Taylor & Francis. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-136-41459-6. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- "How to Throw a Dim Sum Party Like A Pro". Food & Wine. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "How to Cook Frozen Dumplings". www.seriouseats.com. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "7-Eleven champions its dim sum with "Wholehearted, Simple and Tasty" campaign launch". www.marketing-interactive.com. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "7-Eleven Now Sells 'Din Tai Fung' Style Garlic Fried Rice & Here's What We Think". TODAYonline. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Tobin, Meaghan (16 December 2018). "Halal dim sum, airport prayer rooms: how Hong Kong, Japan and Korea won over Muslim travellers". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Tan, G.C. (16 June 2017). "Halal dim sum gains steam". The Star. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Elmira, Putu (7 February 2019). "Kuliner Malam Jumat: Berawal dari Mimpi Makan Dimsum Halal dan Terjangkau" [Friday night culinary: Started from dreaming about eating Halal Dim sum and very affordable]. Liputan 6 (in Indonesian). Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Thiessen, Tamara (2012). Borneo: Sabah, Brunei, Sarawak. Guilford: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 145. ISBN 9781841623900.

- "Four Hong Kong restaurants putting a modern spin on dim sum". South China Morning Post. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Magyarics, Kelly (26 January 2017). "4 Spots for modern take on Dim Sum". DC Refined. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Kirouac, Matt (21 March 2017). "Trend Watch: Dim Sum Goes Beyond Chinatown". Zagat. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- "The best modern dim sum restaurants in Hong Kong". Lifestyle Asia Hong Kong. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Schulman, Amy (5 February 2019). "Hungerlust: One Man Is Reshaping Yum Cha in Hong Kong". Culture Trip. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dim sum. |