Christianity in Australia

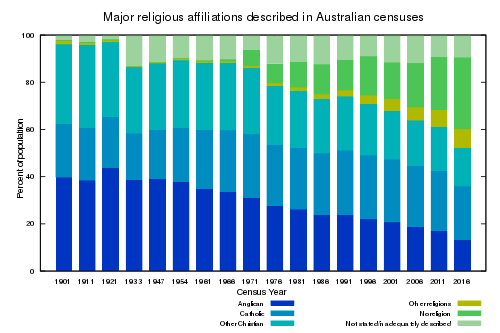

The presence of Christianity in Australia began with the foundation of a British colony at New South Wales in 1788. Christianity remains the largest religion in Australia, though declining religiosity and diversifying immigration intakes of recent decades have seen the percentage of the population identifying as Christian in the national census decline from 96.1% at the time of the Federation of Australia in the 1901 census, to 52.1% in the 2016 census.

| Christianity by country |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Oceania

|

|

South America

|

|

|

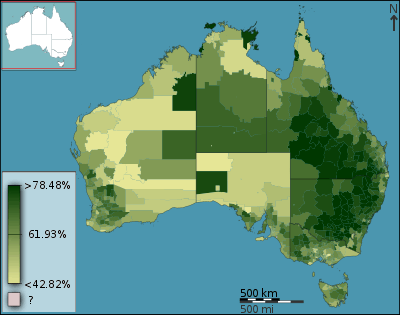

In the 2016 census, Catholics constituted 22.6% of the population, the Anglicans 13.3%, and the Uniting Church had 3.7%. Post-war immigration has grown the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia and there are large and growing Pentecostal groups, such as Sydney's Hillsong Church. According to the 2016 census, Queensland (56.03%) and New South Wales (55.18%) had Christian majorities, while the lowest proportion of Christians were found in the Northern Territory (47.69%) and the Australian Capital Territory (45.38%).[1]

The Christian footprint in Australian society and culture remains broad, particularly in areas of social welfare and education provision and in the marking of festivals such as Easter and Christmas. Though the Australian Constitution of 1901 protects freedom of religion and separation of church and state, the Church of England held legal privileges in the early colonial period, when Catholicism in particular was suppressed, and sectarianism was a feature of Australian politics well into the 20th century, as was collaboration by Church and State in seeking the conversion of the indigenous population to Christianity. Today, the Catholic Church is second only to government as a provider of social services, through organisations such as Catholic Social Services Australia and the St Vincent De Paul Society. The Anglican Church's Anglicare network is similarly engaged in areas such as emergency relief, aged care, family support service and help for the homeless. Other denominations assist through networks like UnitingCare Australia and the Salvation Army, and around a quarter of students attend church owned schools.

Historically significant Australian Christians[2] have included the Reverend John Dunmore Lang, Saint Mary MacKillop, Catherine Helen Spence, Pastor David Unaipon, the Reverend John Flynn, Pastor Sir Doug Nicholls and General Eva Evelyn Burrows of the Salvation Army. High-profile contemporary Australian Christians include Tim Costello; Baptist minister and current CEO of World Vision Australia; Frank Brennan, Jesuit human rights lawyer; John Dickson, historian and founder of The Centre for Public Christianity; Cardinal George Pell, the Vatican's Prefect of the Secretariat for the Economy; Phillip Aspinall the current Archbishop of Brisbane, Philip Freier the current Anglican Primate of Australia and Archbishop of Melbourne; and recent Prime Ministers John Howard, Kevin Rudd, Tony Abbott and Scott Morrison.

History

Introduction of Christianity

Before European contact, indigenous people had performed the rites and rituals of the animist religion of the Dreamtime. Portuguese and Spanish Catholics and Dutch and English Protestants were sailing into Australian waters from the seventeenth century.[4]

Among the first Catholics known to have sighted Australia were the crew of a Spanish expedition of 1605–6. In 1606, the expedition's leader, Pedro Fernandez de Quiros, landed in the New Hebrides and, believing it to be the fabled southern continent, he named the land: Austrialis del Espiritu Santo ("Southern Land of the Holy Spirit").[5][6] Later that year, his deputy Luís Vaz de Torres sailed through Australia's Torres Strait.[7] The English navigator James Cook's favourable account of the fertile east coast of Australia in 1770 ultimately ensured that Australia's Christian foundations were to reflect the British denominations (with their Protestant majority and largely Irish, Catholic minority).

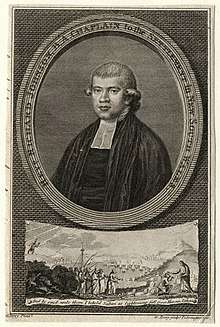

The permanent presence of Christianity in Australia began with the arrival of the First Fleet of British convict ships at Sydney in 1788. The Reverend Richard Johnson of the Church of England was licensed as chaplain to the Fleet and the settlement. In early Colonial times, Church of England clergy worked closely with the governors. Johnson was charged by the governor, Arthur Phillip, with improving "public morality" in the colony, but he was also heavily involved in health and education.[8]

According to Manning Clark, the early colonial officials of the colony had disdain for the "consolations of religion", but shared a view that "the Protestant religion and British institutions were the finest achievements of the wit of man for the promotion of liberty and a high material civilization." Thus they looked to Protestant ministers as the "natural moral policemen of society", of obvious social use in a convict colony for preaching against "drunkenness, whoring and gambling". Chaplain Johnson was an evangelical priest of the Church of England, the first of a series of clergymen, according to Clark, through whom "evangelical Christianity dominated the religious life of Protestant Christianity in Australia throughout the whole of the nineteenth century".[9]

On 7 February 1788, Arthur Phillip was sworn in over the Bible as the first Governor of the colony, and delivered a speech to the convicts counselling the Christian virtues of marriage and an end to promiscuity. Probably on the first Sunday, Chaplain Johnson gathered all those willing under a great tree and offered thanks to God – a week later he celebrated the colony's first Lord's Supper in an officer's tent.[10]

Johnson's successor, the Reverend Samuel Marsden (1765–1838), had magisterial duties and so was equated with the authorities by the convicts. He became known as the "flogging parson" for the severity of his punishments.[11]

Early history of the Catholic Church in Australia

Some of the Irish convicts had been transported to Australia for political crimes or social rebellion in Ireland, so the authorities were suspicious of Catholicism for the first three decades of settlement and Catholic convicts were compelled to attend Church of England services.[12][13]

One-tenth of all the convicts who came to Australia on the First Fleet were Catholic and at least half of them were born in Ireland.[14] A small proportion of British marines were also Catholic. Other groups were also represented, for example, among the Tolpuddle martyrs were a number of Methodists.

It was the crew of the French explorer La Pérouse who conducted the first Catholic ceremony on Australian soil in 1788 – the burial of Father Louis Receveur, a Franciscan friar, who died while the ships were at anchor at Botany Bay, while on a mission to explore the Pacific.[15] The first Catholic priest colonists arrived in Australia as convicts in 1800 – James Harold, James Dixon and Peter O'Neill, who had been convicted for "complicity" in the Irish 1798 Rebellion. Mr Dixon was conditionally emancipated and permitted to celebrate Mass. On 15 May 1803, in vestments made from curtains and with a chalice made of tin he conducted the first Catholic Mass in New South Wales.[12] The Irish led Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804 alarmed the British authorities and Dixon's permission to celebrate Mass was revoked. Fr Jeremiah Flynn, an Irish Cistercian, was appointed as Prefect Apostolic of New Holland and set out from Britain for the colony uninvited. Watched by authorities, Flynn secretly performed priestly duties before being arrested and deported to London. Reaction to the affair in Britain led to two further priests being allowed to travel to the colony in 1820 – John Joseph Therry and Philip Connolly.[13] The foundation stone for the first St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney was laid on 29 October 1821 by Governor Lachlan Macquarie.

The absence of a Catholic mission in Australia before 1818 reflected the legal disabilities of Catholics in Britain. The government therefore endorsed the English Benedictines to lead the early church in the colony.[16] William Bernard Ullathorne (1806–1889) was instrumental in influencing Pope Gregory XVI to establish a Catholic hierarchy in Australia. Ullathorne was in Australia from 1833–1836 as vicar-general to Bishop William Morris (1794–1872), whose jurisdiction extended over the Australian missions.

Foundations of diversification and equality

The Church of England lost its legal privileges in the Colony of New South Wales by the Church Act of 1836. Drafted by the Catholic attorney-general John Plunkett, the act established legal equality for Episcopalians, Catholics and Presbyterians and was later extended to Methodists. Nevertheless, social attitudes were slow to change. Laywoman Caroline Chisholm (1808–1877) faced discouragements and anti-papal feeling when she sought to establish a migrant women's shelter and worked for women's welfare in the colonies in the 1840s, though her humanitarian efforts later won her fame in England and great influence in achieving support for families in the colony.[17]

John Bede Polding, a Benedictine monk, was Sydney's first Catholic bishop (and then archbishop) from 1835 to 1877. Polding requested a community of nuns be sent to the colony and five Irish Sisters of Charity arrived in 1838. The sisters set about pastoral care in a women's prison and began visiting hospitals and schools and establishing employment for convict women.[18] The sisters went on to establish hospitals in four of the eastern states, beginning with St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney in 1857 as a free hospital for all people, but especially for the poor.[19] At Polding's request, the Christian Brothers arrived in Sydney in 1843 to assist in schools. In 1857, Polding founded an Australian order of nuns in the Benedictine tradition – the Sisters of the Good Samaritan – to work in education and social work.[20] While Polding was in office, construction began on the ambitious Gothic Revival designs for St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne and the final St Mary's Cathedral in Sydney.

Since the 19th century, immigrants have brought their own expressions of Christianity with them. Particular examples are the Lutherans from Prussia who tended to settle in the Barossa Valley, South Australia and in Queensland, Methodists in South Australia, with notable pockets coming from Cornwall to work the copper mines in Moonta. Other groups included the Presbyterian, Congregationalist and Baptist churches. Establishing themselves first at Sevenhill, in the newly established colony of South Australia in 1848, the Jesuits were the first religious order of priests to enter and establish houses in South Australia, Victoria, Queensland and the Northern Territory. While the Austrian Jesuits traversed the Outback on horseback to found missions and schools, Irish Jesuits arrived in the east in 1860 and had by 1880 established the major schools which survive to the present.[21]

In 1885, Patrick Francis Moran became Australia's first cardinal. Moran believed that Catholics' political and civil rights were threatened in Australia and, in 1896, saw deliberate discrimination in a situation where "no office of first, or even second, rate importance is held by a Catholic".[22]

The Churches became involved in mission work among the Aboriginal people of Australia in the 19th century as Europeans came to control much of the continent and the majority of the population was eventually converted. Colonial clergy such as Sydney's first Catholic archbishop, John Bede Polding, strongly advocated for Aboriginal rights and dignity[23]

With the withdrawal of state aid for church schools around 1880, the Catholic Church, unlike other Australian churches, put great energy and resources into creating a comprehensive alternative system of education. It was largely staffed by nuns, brothers and priests of religious orders, such as the Christian Brothers (who had returned to Australia in 1868); the Sisters of Mercy (who had arrived in Perth in 1846); Marist Brothers, who came from France in 1872 and the Sisters of St Joseph, founded in Australia by Saint Mary MacKillop and Fr Julian Tenison Woods in 1867.[24][25][26] MacKillop travelled throughout Australasia and established schools, convents and charitable institutions but came into conflict with those bishops who preferred diocesan control of the order rather than central control from Adelaide by the Josephite order. MacKillop administered the Josephites as a national order at a time when Australia was divided among individually governed colonies. She is today the most revered of Australian Catholics, canonised by Benedict XVI in 2010.[27]

Also from Britain came the Salvation Army (its members sometimes called "Salvos" in Australia), which had been established in the slums of East London in 1865 to minister to the impoverished outcasts of the city. The first Salvation Army meeting in Australia was held in 1880. Edward Saunders and John Gore led the meeting from the back of a greengrocer's cart in Adelaide Botanic Park with an offer of food for those who had not eaten.[28] The Salvos also involved themeselves in finding work for the unemployed and in re-uniting families. In Melbourne from 1897 to 1910, The Army's Limelight Department was established as Australia's first film production company.[29] From such diverse activities, The Salvos have grown to be one of Australia's most respected charitable organisations, with a 2009 survey by Sweeney Research and the advertising group Grey Global finding the Salvation Army and the nation's Ambulance Service to be Australia's most trusted entities.[30] Australia's George Carpenter was General of the Salvation Army (worldwide leader) from 1939–1946 and Eva Burrows during the 1980s and 1990s.[31][32]

Commonwealth of Australia

Section 116 of the Australian Constitution of 1901 provided for freedom of religion.[33] With the exception of the indigenous population, descendants of gold rush migrants and a small but significant Lutheran population of German descent, Australian society was predominantly Anglo-Celtic, with 40% of the population being Church of England, 23% Catholic, 34% other Christian and about 1% professing non-Christian religions. The first census in 1911 showed 96.1 per cent identified themselves as Christian.

Sectarianism in Australia tended to reflect the political inheritance of Britain and Ireland. Until 1945, the vast majority of Catholics in Australia were of Irish descent, causing the Anglo-Protestant majority to question their loyalty to the British Empire.[13] The Church of England remained the largest Christian church until the 1986 census. After World War II, the ethnic and cultural mix of Australia diversified and the Church of England gave way to the Catholic Church as the largest. The number of Anglicans attending regular worship began to decline in 1959 and figures for occasional services (baptisms, confirmations, weddings and funerals) started to decline after 1966.[34]

Further waves of migration and the gradual winding back of the White Australia Policy, helped to reshape the profile of Australia's religious affiliations over subsequent decades. The impact of migration from Europe in the aftermath of World War II led to increases in affiliates of the Orthodox churches, the establishment of Reformed bodies, growth in the number of Catholics (largely from Italian migration) and Jews (Holocaust survivors). More recently (post-1970s), immigration from South-East Asia and the Middle East has expanded Buddhist and Muslim numbers considerably and increased the ethnic diversity of the existing Christian churches.

Russian sailors visiting Sydney celebrated the Divine Liturgy as long ago as 1820 and a Greek Orthodox population emerged from the mid-19th century. The Greeks of Sydney and Melbourne had a priest by 1896 and the first Greek Orthodox church was opened at Surry Hills in Sydney in 1898. In 1924, the Metropolis of Australia and New Zealand was established under the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Greek immigration increased considerably following World War II, and the Metropolis of Australia and New Zealand was elevated to Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia and Metropolitan Ezekiel was appointed archbishop in 1959. Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew visited Australia in November 1996.[35]

In the 1970s, the Methodist, Presbyterian and Congregational churches in Australia united to form the Uniting Church in Australia.[36] The church remains prominent in welfare services and noted for its innovative ministry initiatives such as those pioneered at centres like Sydney's Wayside Chapel in King's Cross.

1970 saw the first visit to Australia by a Pope, Paul VI.[37] Pope John Paul II was the next Pope to visit Australia in 1986. At Alice Springs, the Pope made an historic address to indigenous Australians, in which he praised the enduring qualities of Aboriginal culture, lamented the effects of dispossession of and discrimination; called for acknowledgment of Aboriginal land rights and reconciliation in Australia; and said that the Christian Church in Australia would not reach its potential until Aboriginal people had made their "contribution to her life and until that contribution has been joyfully received by others".[38] In July 2008, Sydney hosted the massive international youth festival "World Youth Day" led by Pope Benedict XVI.[39][40] Around 500,000 welcomed the pope to Sydney and 270,000 watched the Stations of the Cross. More than 300,000 pilgrims camped out overnight in preparation for the final Mass,[41] where final attendance was between 300,000 and 400,000 people.[42][43][44]

In recent times, the Christian churches of Australia have been active in ecumenical activity. The Australian Committee for the World Council of Churches was established in 1946 by the Anglican and mainline Protestant churches. The movement evolved and expanded with Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches later joining and by 1994 the Catholic Church was also a member of the national ecumenical body, the National Council of Churches in Australia. A 2015 study estimates some 20,000 Muslim converted to Christianity in Australia, most of them belonging to some form of Protestantism.[45]

Percentage of population since 1901

| Census year | Anglican % | Catholic % | Other Christian % | Total Christian % | Total population counted '000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 39.7 | 22.7 | 33.9 | 96.1 | 3,773.7 |

| 1911 | 38.4 | 22.4 | 35.1 | 95.9 | 4,455.0 |

| 1921 | 43.7 | 21.7 | 31.6 | 96.9 | 5,435.7 |

| 1933 | 38.7 | 19.6 | 28.1 | 86.4 | 6,629.8 |

| 1947 | 39.0 | 20.9 | 28.1 | 88.0 | 7,579.4 |

| 1954 | 37.9 | 22.9 | 28.5 | 89.4 | 8,986.5 |

| 1961 | 34.9 | 24.9 | 28.4 | 88.3 | 10,508.2 |

| 1966 | 33.5 | 26.2 | 28.5 | 88.2 | 11,599.5 |

| 1971 | 31.0 | 27.0 | 28.2 | 86.2 | 12,755.6 |

| 1976 | 27.7 | 25.7 | 25.2 | 78.6 | 13,548.4 |

| 1981 | 26.1 | 26.0 | 24.3 | 76.4 | 14,576.3 |

| 1986 | 23.9 | 26.0 | 23.0 | 73.0 | 15,602.2 |

| 1991 | 23.8 | 27.3 | 22.9 | 74.0 | 16,850.3 |

| 1996 | 22.0 | 27.0 | 21.9 | 70.9 | 17,752.8 |

| 2001 | 20.7 | 26.6 | 20.7 | 68.0 | 18,769.2 |

| 2006 | 18.7 | 25.8 | 19.3 | 63.9 | 19,855.3 |

| 2011 | 17.1 | 25.3 | 18.7 | 61.1 | 21,507.7 |

| 2016 | 13.3 | 22.6 | 16.2 | 52.2 | 23,401.4 |

Data for table up to 2006 from Australian Bureau of Statistics.[3]

Indigenous Australians and Christianity

Christianity and European culture have had a significant impact on Indigenous Australians, their religion and their culture. As in many colonial situations the churches both facilitated the loss of Indigenous Australian culture and religion and also facilitated its maintenance. The involvement of Christians in Aboriginal affairs has evolved significantly since 1788. Around the year 2000, many churches and church organisations officially apologised for past failures to adequately respect indigenous cultures and address the injustices of the dispossession of indigenous people.[46][47][48]

Christian missionaries often witnessed to Indigenous people in an attempt to convert them to Christianity. The Presbyterian Church of Australia’s Australian Inland Mission and the Lutheran mission at Hermannsburg, Northern Territory being examples. Many missionaries often studied Aboriginal society from an Anthropological perspective.[49] Missionaries have made significant contributions to anthropological and linguistic understanding of Indigenous Australians and aspects of Christian services have been adapted when there is Aboriginal involvement – even masses during Papal visits to Australia will include traditional Aboriginal smoking ceremonies.[50] It was the practice of some Missions to enforce a 'forgetting' of Aboriginal culture. Others, like Fr Kevin McKelson of Broome encouraged aboriginal culture and language while also promoting the merits of western style education in the 1960s.[51]

Prominent Aboriginal activist Noel Pearson, himself raised at a Lutheran mission in Cape York, has written that missions throughout Australia's colonial history "provided a haven from the hell of life on the Australian frontier while at the same time facilitating colonisation".[52]

In the Torres Strait Islands, the Coming of the Light Festival marks the day the Christian missionaries first arrived on the islands on 1 July 1871 and introduced Christianity to the region. This is a significant festival for Torres Strait Islanders, who are predominantly Christian. Religious and cultural ceremonies are held across Torres Strait and mainland Australia.[53]

Prominent Aboriginal Christians[54] have included Pastor David Unaipon, the first Aboriginal author; Pastor Sir Douglas Nicholls, athlete, activist and former Governor of South Australia; Mum (Shirl) Smith, a celebrated Redfern community worker who, assisted by the Sisters of Charity, worked in the courts and organised prison visitations, medical and social assistance for Aborigines,[49] and former Senator Aden Ridgeway, the first Chairman of the Aboriginal Catholic Ministry.[49] The Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress, associated with the Uniting Church in Australia, is an organisation developed and managed by Indigenous people to "provide spiritual, social and economic pathways for Australia's First People".[55]

In recent times, Christians like Fr Ted Kennedy of Redfern,[56] Jesuit human rights lawyer Fr Frank Brennan[57] and the Josephite Sisters have been prominent in working for Aboriginal rights and improvements to standards of living.[58]

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Catholic Council[59] is the peak body representing Indigenous Catholics in Australia and was formed in Cairns in January 1989 at the first National Conference of the Aboriginal and Islander Catholic Councils. In 1992 the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference officially recognised and welcomed it as the national representative and consultative body to the church on issues concerning Indigenous Catholics.

The members of the council stand down every three years and a new council is appointed. NATSICC's funding comes in the form of Voluntary contributions from schools, parishes and religious orders. In addition, Caritas Australia provides ongoing funding.

Encouraged by Pope John Paul II's words in the Post Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Ecclesia in Oceania NATSICC is determined to continue, as the peak Indigenous Catholic representative body, to actively support and promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in the Catholic Church in Australia.

Social and political engagement

History

Christian charitable organisations, hospitals and schools have played a prominent role in welfare and education since Colonial times, when the First Fleet's Church of England chaplain, Richard Johnson, was credited as "the physician both of soul and body" during the famine of 1790 and was charged with general supervision of schools.[8] The Catholic laywoman Caroline Chisolm helped single migrant women and rescued homeless girls in Sydney.[60] In his welcoming address to the Catholic World Youth Day 2008 in Sydney the then Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, said that Christianity had been a positive influence on Australia: "It was the church that began first schools for the poor, it was the church that began first hospitals for the poor, it was the church that began first refuges for the poor and these great traditions continue for the future."[61]

Welfare

A number of Christian churches are significant national providers of social welfare services (including residential aged care and the Job Network) and education. These include:

- The Salvation Army. In 2012, the Australian prime minister, Julia Gillard (herself not religious but with family connections to the work of Salvation Army), praised the welfare work of the Salvation Army in Australia as "Christianity with its sleeves rolled up" and which, she said, was each week reuniting 40 Australian families; assisting 500 drug, alcohol or gambling addiction affected people; providing 2000 homeless with shelter; and counselling thousands more.[62]

- The Uniting Church in Australia does extensive community work in aged care, hospitals, nursing, family support services, youth services and with the homeless. Services include UnitingCare Australia, Exodus Foundation, the Wesley Missions and Lifeline counseling.[14]

- The Anglican Church of Australia has organisations working in education, health, missionary work, social welfare and communications. Organisations include Anglicare and the Samaritans.

- The Catholic Church: Catholic Social Services Australia is the church's peak national body. Its 63 member organisations help more than a million Australians each year. Catholic organisations include: Centacare, Caritas Australia, Jesuit Refugee Service, St Vincent de Paul Society, Josephite Community Aid; Fr. Chris Riley's Youth Off The Streets; Edmund Rice Camps; and the Bob Maguire Foundation. Two religious orders founded in Australia which engaged in welfare and charity work are the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart and the Sisters of the Good Samaritan.[13] Many international orders also work in welfare, such as the Little Sisters of the Poor who work in aged care and the Sisters of Charity of Australia, who have played a prominent role in healthcare and women's welfare in Australia since the 1830s.

- Hillsong Church's Hillsong Emerge is a local example in Sydney, New South Wales.

- The Baptist Church's Tim Costello is CEO of World Vision Australia.

- Other Christian humanitarian aid organisations operating in Australia include: Christian Children's Fund, Christian Blind Mission International; Mission Australia; St Luke's, the Christian Blind Mission; Compassion Australia; St John Ambulance Australia;

Health

Catholic Health Australia is the largest non-government provider grouping of health, community and aged care services in Australia. These do not operate for profit and range across the full spectrum of health services, representing about 10% of the health sector and employing 35,000 people.[63] Catholic religious orders founded many of Australia's hospitals. Irish Sisters of Charity arrived in Sydney in 1838 and established St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney in 1857 as a free hospital for the poor. The Sisters went on to found hospitals, hospices, research institutes and aged care facilities in Victoria, Queensland and Tasmania.[64] At St Vincent's they trained leading surgeon Victor Chang and opened Australia's first AIDS clinic.[65] In the 21st century, with more and more lay people involved in management, the sisters began collaborating with Sisters of Mercy Hospitals in Melbourne and Sydney. Jointly the group operates four public hospitals; seven private hospitals and 10 aged care facilities. The English Sisters of the Little Company of Mary arrived in 1885 and have since established public and private hospitals, retirement living and residential aged care, community care and comprehensive palliative care in New South Wales, the ACT, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and the Northern Territory.[66] The Little Sisters of the Poor, who follow the charism of Saint Jeanne Jugan to 'offer hospitality to the needy aged' arrived in Melbourne in 1884 and now operate four aged care homes in Australia.[67]

An example of a Christian Welfare agency is ADRA (Adventist Development and Relief Agency).[68] This welfare agency is an internationally recognized agency run by the Seventh-day Adventist Church. ADRA is operational in more than 120 countries, around the world, providing relief and development, where ever needed. Within Australia they provide shelter, relief, and services to those in need. They have numerous refuges set up those suffering abuse, as well as shelters for those in need. As well many other things such as food distribution, op-shops etc.

The Reverend John Flynn, a minister of the Presbyterian Church founded what was to become the Royal Flying Doctor Service in 1928 in Cloncurry, Queensland, to bring health services to the isolated communities of the Australian The Bush.[69]

Education

There are substantial networks of Christian schools associated with the Christian churches and also some that operate as parachurch organisations. The Catholic education system is the second biggest sector after government schools and has more than 730,000[70] students and around 21 per cent of all secondary school enrolments. The Catholic Church has established primary, secondary and tertiary educational institutions in Australia. The Anglican Church has around 145 schools in Australia, providing for more than 105,000 children. The Uniting Church has around 48 schools [14][71] as does the Seventh-day Adventist Church.[72]

Mary MacKillop was a 19th-century Australian nun who founded an educational order, the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart, and has recently become the first Australian to be canonised as a saint by the Catholic Church.[73] Other Catholic religious orders involved in education in Australia have included: Sisters of Mercy, Marist Brothers, Christian Brothers, Benedictine Sisters, Jesuits and The Missionaries of the Sacred Heart.

Church schools range from elite, high cost schools to low fee locally based schools. Churches with networks of schools include:

- Anglican

- Catholic

- Uniting Church

- Baptist

- Eastern Orthodox

- Lutheran

- Nondenominational

The Australian Catholic University opened in 1991 following the amalgamation of four Catholic tertiary institutions in eastern Australia. These institutions had their origins in the 19th century, when religious orders and institutes became involved in preparing teachers for Catholic schools and nurses for Catholic hospitals.[74] The University of Notre Dame Australia opened in Western Australia in December 1989, and now has over 9000 students on three campuses in Fremantle, Sydney and Broome.[75]

Politics

Church leaders have often involved themselves in political issues in areas they consider relevant to Christian teachings. In early Colonial times, Catholicism was restricted but Church of England clergy worked closely with the governors. The Reverend Samuel Marsden had magisterial duties and so was equated with the authorities by the convicts. He became known as the "floging parson" for the severity of his punishments.[11] An early Catholic missionary, William Ullathorne, criticised the convict system, publishing a pamphlet, The Horrors of Transportation Briefly Unfolded to the People, in Britain in 1837.[76] Australia's first Catholic cardinal, Patrick Francis Moran (1830–1911), was politically active. As a proponent of Australian Federation he denounced anti-Chinese legislation as "unchristian"; became an advocate for women's suffrage and alarmed conservatives by supporting trade unionism and "Australian socialism".[77] Archbishop Daniel Mannix of Melbourne was a controversial voice against conscription during World War I and against British policy in Ireland.[78]

Aboriginal pastors David Unaipon and Sir Douglas Nicholls, former Catholic priest Pat Dodson and Jesuit priest Frank Brennan have been high-profile Christians engaged in the cause of Aboriginal rights.[57][79][80]

The Australian Labor Party had largely been supported by Catholics until prominent layman B. A. Santamaria formed the Democratic Labor Party over concerns of Communist influence over the trade union movement in the 1950s.[81]

In 1999, Catholic cardinal Edward Clancy wrote to the prime minister, John Howard, urging him to send an armed peacekeeping force to East Timor to end the violence engulfing that country.[82] Previous Archbishops of Sydney, Cardinal George Pell (Catholic) and Peter Jensen (Anglican), have concerned themselves with traditional issues of Christian doctrine, such as marriage or abortion, but have also raised questions about government policies such as the Work Choices industrial relations reforms and the mandatory detention of asylum seekers.[83][84] Tim Costello, a Baptist minister and the CEO of World Vision Australia, has often been vocal on issues of welfare, foreign aid and climate change.[85]

Politicians

When taking their oath of office, ministers in the Australian federal government may elect to swear that oath on the Bible. In 2007, half of the 40 member cabinet of the Rudd Government chose to do so.[86] Historically most Australian prime ministers have been Christians of varying denominations. Of recent prime ministers, Bob Hawke is an agnostic son of a Congregational minister; Paul Keating is a practising Catholic; John Howard and Kevin Rudd are practising Anglicans, and Tony Abbott is a practising Catholic.[81][87][88][89] Former Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, was raised by Christian parents but is herself an atheist.

Religion is often kept "low-key" as topic of discussion in politics in Australia, but a number of current and past politicians present themselves as Christian in public life, these include:

- Federally: Scott Morrison (Pentecostal, Prime Minister), Tony Abbott (Catholic, Former Prime Minister), Kevin Rudd (Anglican, former Catholic, Former Prime Minister), Joe Hockey, (Catholic, Treasurer) Christopher Pyne (Catholic, Liberal MP), Andrew Robb, (Catholic, Liberal Party of Australia), Kevin Andrews, (Catholic, Liberal Party of Australia MP). Historically, most Australian prime ministers have been Christians and recent oppositions leaders Kim Beazley (Anglican); Brendan Nelson and Malcolm Turnbull (Catholic) were all practising Christians. Prominent senators Brian Harradine, Tasmanian independent (1975–2005) and Steve Fielding (Pentecostal, Family First former senator) often referred to their Christianity and Brian Howe Labor Deputy Prime Minister (1991–1995). Though the monarch is not the head of the Anglican Church of Australia, the monarch must be in communion with the Anglican Church of Australia. In recent decades, Pastor Doug Nicholls served as Governor of South Australia and Archbishop Peter Hollingsworth served as Governor General of Australia.

- State: Former New South Wales premier Kristina Keneally is a theology graduate and another former premier, John Fahey, is a former seminarian. The Reverend Fred Nile and the Reverend Gordon Moyes have been two long serving members of the New South Wales Legislative Council. Andrew Evans in the South Australian Legislative Council and Joh Bjelke Petersen Premier of Queensland (1968 to 1987) were also Christians. NSW premier Mike Baird and NSW Commissioner of Police Andrew Scipione are both Christians.

The Parliamentary Christian Fellowship, also known as the Parliamentary prayer group, is a gathering of Christian politicians in the Australian parliament, who hold prayer sessions on Monday nights in Parliament House, Canberra.

Culture and the arts

Festivals

The Christian festivals of Christmas and Easter are marked as public holidays in Australia.

Christmas

The Christian festival of Christmas celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ. As in most Western nations, Christmas in Australia is an important time even for non-religious people and is generally celebrated on 25 December. Churches of the Western Christian tradition hold Christmas Day services on this day but most churches of Eastern Christian tradition – Ethiopian Orthodox, Russian Orthodox or the Armenian Church celebrate Christmas on 6 or 7 January. Both Christmas Day and 26 December (Boxing Day) are public holidays throughout Australia.[90]

Although Christmas in Australia is celebrated during the Southern Hemisphere summer, many Northern Hemisphere traditions are observed in Australia – families and friends exchange Christmas cards and gifts and gather for Christmas dinners; sing songs about snow and sleighbells; decorate Christmas trees; and tell stories of Santa Claus. Nevertheless, local adaptations have arisen – large open-air carol concerts are conducted on summer evenings before Christmas – such as the Carols by Candlelight in Melbourne and Sydney's Carols in the Domain. The Christmas song Six White Boomers, by Rolf Harris, tells of Santa undertaking his flight around Australia hauled by six white-boomer kangaroos in place of reindeer. Christian carols such as Three Drovers or Christmas Day by John Wheeler and William G. James place the hymns of praise firmly in an Australian context of warm, dry Christmas winds and red dust. Although a hot roast dinner remains a favourite Christmas meal, the summer temperatures can tempt some Australians toward the nearest watercourses to cool down between feasts. It is a tradition for international visitors to gather en masse at Sydney's Bondi Beach on Christmas Day.

The Assyrian Church of the East is also known to be a crowd drawer for the special Christmas Eve midnight mass. More than 15,000 faithful gather at churches in Sydney, notably the St Hurmizd Cathedral in Sydney's west.

Easter

The Christian festival of Easter commemorates the Bible's account of the Crucification and Resurrection of Jesus Christ. In Australia, in addition to the religious significance of Easter for Christians, the festival is marked by a four-day holiday weekend starting on Good Friday and ending on Easter Monday – which generally coincides with school holidays and is an opportunity for family and friends to travel and reunite. Across Australia, church services are well attended, as are secular music festivals, fairs and sporting events. One such Easter event is Easterfest an annual Christian Music Festival in Queen's Park Toowoomba and known as the largest drug and alcohol free festival in Australia.[91]

Traditional Easter foods commonly consumed in Australia include Hot Cross Buns, recalling the cross of the Crucifixion, and chocolate Easter Eggs – symbolic of the promise of New Life offered by the Resurrection. Although chocolate eggs are now eaten throughout the period, eggs were traditionally exchanged on Easter Sunday and, as in other nations, young children believe their eggs to be delivered by the Easter Bunny. A local variant on this tradition is the story of the Easter Bilby, which seeks to raise the profile of an endangered Australian native, the Bilby whose existence is threatened by the imported European rabbit population.[92]

Other Easter traditions have been brought by migrant communities to Australia. Greek Orthodox traditions have a wide following among descendants of Greek immigrants; and a fishermen's tradition brought from Sicily, the Ulladulla Blessing of the Fleet, takes place on the New South Wales South Coast with St Peter as patron.[93]

Architecture

See also

Most towns in Australia have at least one Christian church. One of Australia's oldest is St. James Church, Sydney, built between 1819 and 1824. The historic Anglican church was designed by Governor Macquarie's architect, Francis Greenway – a former convict – and built with convict labour. It is set on a sandstone base and built of face brick with the walls articulated by brick piers.[94] Sydney's Anglican Cathedral of St Andrew was consecrated in 1868 from foundations laid in the 1830s. Largely designed by Edmund Thomas Blacket in the Perpendicular Gothic style reminiscent of English cathedrals. Blacket also designed St Saviour's Goulburn Cathedral, based on the Decorated Gothic style of a large English parish church and built between 1874–1884.[95]

The "mother church" of Catholicism in Australia is St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney. The plan of the cathedral is a conventional English cathedral plan, cruciform in shape, with a tower over the crossing of the nave and transepts, and twin towers at the West Front, with impressive stained glass windows. 106.7 metres in length and a general width 24.4 metres, it is Sydney's largest church. Built to a design by William Wardell from a foundation stone laid in 1868, the spires of the Cathedral were not finally added until the year 2000.

Wardell also worked on the design of St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne – considered among the finest examples of ecclesiastical architecture in Australia.[96][97] Wardell's overall design was in Gothic Revival style, paying tribute to the mediaeval cathedrals of Europe. Largely constructed between 1858 and 1897, the nave was Early English in style, while the remainder of the building is in Decorated Gothic. St Paul's Anglican Cathedral, from a foundation stone laid in 1880, is another Melbourne landmark. It was designed by distinguished English architect William Butterfield in Gothic Transitional.[98]

Tasmania is home to a number of significant colonial Christian buildings including those located at Australia's best preserved convict era settlement, Port Arthur. According to 19th century notions of prisoner reform, the "Model Prison" incorporates a grim chapel into which prisoners in solitary confinement were shepherded to listen (in individual enclosures) to the preacher's Sunday sermon – their only permitted interaction with another human being.[99] Adelaide, the capital of South Australia has long been known as the "City of Churches" and its St Peter's Anglican Cathedral is a noted city landmark.[100] 130 km north of Adelaide is the Jesuit old stone winery and cellars at Sevenhill, founded by Austrian Jesuits in 1848.[101]

The oldest building in the city of Canberra is the picturesque St John the Baptist Anglican Church in Reid, consecrated in 1845. This church long pre-dates the city of Canberra and is not so much representative of urban design as it is of the Bush chapels which dot the Australian landscape and stretch even into the far Outback, such as that which can be found at the Lutheran Mission Chapel at Hermannsburg in the Northern Territory. A rare Australian example of Spanish missionary style exists at New Norcia, Western Australia. Founded by Spanish Benedictine monks in 1846.[102][103]

A number of notable Victorian era chapels and edifices were also constructed at church schools across Australia.

Along with community attitudes to religion, church architecture changed significantly during the 20th century. Urban churches such as that at the Wayside Chapel (1964) in Sydney differed markedly from traditional ecclesiastical designs. St Monica's Cathedral in Cairns was designed by architect Ian Ferrier and built in 1967–68 following the form of the original basilica model of the early churches of Rome, adapted to a tropical climate and to reflect the changes to Catholic liturgy mandated at Vatican 2. The cathedral was dedicated as a memorial to the Battle of the Coral Sea which was fought east of Cairns in May 1942. The "Peace Window" stained glass was installed on the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II.[104]

In the later 20th century, distinctly Australian approaches were applied at places such as Jambaroo Benedictine Abbey, where natural materials were chosen to "harmonise with the local environment". The chapel sanctuary is of glass overlooking rainforest.[105] Similar design principles were applied at Thredbo Ecumenical Chapel built in the Snowy Mountains in 1996.[106]

Film

The Salvation Army founded one of the world's first ever movie studios in Melbourne in the 1890s: the Limelight Department. First filming A Melbourne Street Scene in 1897, they went on to make large scale Christian themed audio-visual presentations such as Soldiers of the Cross in 1900, and documented the Australian Federation ceremonies of 1901.[107]

Australian films on Christian themes have included:

- Molokai: The Story of Father Damien (1999), directed by Paul Cox and starring David Wenham. The film recounts the life of a Belgian saint, Fr Damien of Molokai who devoted his life to care of lepers on a Hawaiian Island.

- Mary (1994), directed written and directed by Kay Pavlou and starring Lucy Bell. A biopic recounting the life and works of Saint Mary MacKillop, Australia's first canonised saint of the Catholic Church.

- The Passion of the Christ (2004) was directed, co-produced and co-written by Australian trained actor-director Mel Gibson (who was raised a Traditionalist Catholic in Australia).

Media

A number of current and past media personalities present themselves as Christian in public life, these include Brooke Fraser, Dan Sweetman, and Guy Sebastian.

Father Bob Maguire and Reverend Gordon Moyes have hosted radio programs.

Coverage of religion is part of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Charter obligation to reflect the character and diversity of the Australian community. Its religious programs include coverage of worship and devotion, explanation, analysis, debate and reports.[108]

Catholic Church Television Australia is an office with the Australian Catholic Office for Film & Broadcasting and develops television programs for Aurora Community Television on Foxtel and Austar in Australia.[109]

Literature

A Bush Christening is a popular comic bush ballad by renowned Australian poet Banjo Paterson which makes light of the sparsity of Christian preachers and houses of worship on the Australian frontier, beginning:

- On the outer Barcoo where the churches are few,

- And men of religion are scanty...

Nevertheless, the body of literature produced by Australian Christians is extensive. During colonial times, the Benedictine missionary William Ullathorne (1806–1889) was a notable essayist writing against the Convict Transportation system. Later Cardinal Moran (1830–1911), a noted historian, wrote a History of the Catholic Church in Australasia.[12] More recent Catholic histories of Australian include The Catholic Church and Community in Australia (1977) by Patrick O'Farrell and Australian Catholics (1987), by Edmund Campion.

Notable Christian poets have included Christopher Brennan (1870–1932) and James McAuley (1917–1976),[110] Bruce Dawe (born 1930). Dawe is among Australia's foremost contemporary poets, noted for his use of vernacular and everyday Australian themes.[111][112]

Australian literature for a long time assumed knowledge of Biblical stories, even where works of literature are not overtly Christian in character. The writings of great 20th century authors like Manning Clark or Patrick White are therefore filled with allusions to biblical or Christian themes.[111]

Many Australian writers have examined the lives of Christian characters, or have influenced by Christian educations. Best selling author Tim Winton.s early novel That Eye, the Sky tells the story of a family's conversion to Christianity in the face of tragedy. Australia's best selling novel of all time, The Thornbirds, by Colleen McCullough writes of the temptations encountered by a priest living in the Outback.

Many contemporary Australian writers including Peter Carey and Robert Hughes; leading screenwriters Nick Enright, Bruce Beresford, Peter Weir, Santo Cilauro and Tom Gleisner; and notable poets and authors like Kenneth Slessor, Helen Garner and Gerard Windsor attended Anglican, Presbyterian or Catholic schools in Australia.

In 2011, Prime Minister and atheist Julia Gillard, said that it was important for Australians to have knowledge of the Bible, on the basis that "what comes from the Bible has formed such an important part of our culture. It's impossible to understand Western literature without having that key of understanding the Bible stories and how Western literature builds on them and reflects them and deconstructs them and brings them back together."[113]

Art

The story of Christian art in Australia began with the arrival of the first British settlers at the end of the 18th Century. During the 19th Century, Gothic Revival Cathedrals were built in the Colonial capitals, often containing stained glass art works, as can be seen at St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney and St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne. Rupert Bunny (1864–1947), one of the first Australian painters to gain international fame, often painted Christian themes (see Annunciation, 1893).[114] Roy de Maistre (1894–1968) was an Australian abstract artist who obtained renown in Britain, converted to Catholicism and painted notable religious works, including a series of Stations of the Cross for Westminster Cathedral. Among the most acclaimed of Australian painters of Christian themes was Arthur Boyd. Influenced by both the European masters and the Heidelberg School of Australian landscape art, he placed the central characters of the bible within Australian bush scenery, as in his portrait of Adam and Eve, The Expulsion (1948).[115] Artist Leonard French, who designed a stained glass ceiling of the National Gallery of Victoria, has drawn heavily on Christian story and symbolism through his career.[116]

From the 1970s, Australian Aboriginal artists of the Western Desert began to paint traditional style artworks in acrylic paints. This distinctively Australian style of painting has been fused with biblical themes to produce a uniquely Australian contribution to the long history of Christian art: integrating the mysterious dot designs and evocative circular patterns of traditional Aboriginal art with popular Christian subjects.[117]

The Blake Prize for Religious Art was established in 1951 as an incentive to raise the standard of religious art in Australia and was named after the artist and poet William Blake.[118]

Music

.jpg)

Christian music arrived in Australia with the First Fleet of British settlers in 1788 and has grown to include all genres from traditional Hymns of Praise to Christian Rock and country music. St Mary's Cathedral Choir, Sydney is the oldest musical institution in Australia, from origins in 1817.[119] Major recording artists from Johnny O'Keefe (the first Australian Rock and Roll star) to Paul Kelly (folk rock), Nick Cave (the critically acclaimed brooding rocker) and Slim Dusty (the King of Australian country music) have all recorded Christian themed songs. Other performing artists such as Catholic nun Sister Janet Mead, Aboriginal crooner Jimmy Little and Australian Idol contestant Guy Sebastian have held Christianity as central to their public persona.

Church music also ranges widely across genres, from Melbourne's St Paul's Cathedral Choir who sing choral evensong most weeknights; to the Contemporary music that is a feature of the evangelical Hillsong congregation.[120][121] The Ntaria Choir at Hermannsburg, Northern Territory, has a unique musical language which mixes the traditional vocals of the Ntaria Aboriginal women with Lutheran chorales (tunes that were the basis of much of Bach's music). Baba Waiyar, a popular traditional Torres Strait Islander hymn shows the influence of gospel music mixed with traditionally strong Torres Strait Islander vocals and country music.[122]

Annually, Australians gather in large numbers for traditional open-air Christmas music Carols by Candlelight concerts in December, such as the Carols by Candlelight of Melbourne, and Sydney's Carols in the Domain. Australian Christmas carols like the Three Drovers or Christmas Day by John Wheeler and William G. James place the Christmas story firmly in an Australian context of warm, dry Christmas winds and red dust.[90]

New South Wales Supreme Court Judge George Palmer was commissioned to compose the setting of the Mass for Sydney's World Youth Day 2008 Papal Mass. The Mass, Benedictus Qui Venit, for large choir, soloists and orchestra, was performed in the presence of Pope Benedict XVI and an audience of 350,000 with singing led by soprano Amelia Farrugia and tenor Andrew Goodwin. "Receive the Power" a song written by Guy Sebastian and Gary Pinto was chosen as official anthem for the XXIII World Youth Day (WYD08) held in Sydney in 2008.[123]

Denominations

| Christian denominations in Australia |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other |

Church affiliation

The churches with the largest number of members are the Catholic Church in Australia, the Anglican Church of Australia and the Uniting Church in Australia. Pentecostal churches are growing with megachurches, predominantly associated with Australian Christian Churches (the Assemblies of God in Australia), being found in most states (for example, Hillsong Church and Paradise Community Church).[124]

Australian Bureau of Statistics

As at the 2016 census, 12,201,600, representing 52.1% of the total population, declared a religious affinity with Christianity.[125][126]

| Affiliation | 1986 census | 1996 census | 2006 census[128] | 2016 census[125][126] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| '000s | % of all Christians | '000s | % of all Christians | '000s | % of all Christians | actuals | % of all Christians | |||

| Anglican | 3723.4 | 32.7% | 3903.3 | 31.0% | 3718.3 | 29.3% | 3,101,191 | 25.4% | ||

| Baptist | 196.8 | 1.7% | 295.2 | 2.3% | 316.7 | 2.5% | 345,142 | 2.8% | ||

| Catholic | 4064.4 | 35.7% | 4799 | 38.1% | 5126.9 | 40.4% | 5,291,830 | 43.4% | ||

| Churches of Christ | 88.5 | 0.8% | 75 | 0.6% | 54.8 | 0.4% | 39,622 | 0.3% | ||

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 66.5 | 0.6% | 83.4 | 0.7% | 80.9 | 0.6% | 82,510 | 0.7% | ||

| Latter Day Saints | 35.5 | 0.3% | 45.2 | 0.4% | 53.1 | 0.4% | 61,639 | 0.5% | ||

| Lutheran | 208.3 | 1.8% | 250 | 2.0% | 251.1 | 2.0% | 174,019 | 1.4% | ||

| Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodoxy, and Assyrian Apostolic | 427.4 | 3.8% | 497.3 | 4.0% | 544.3 | 4.3% | 567,680 | 4.7% | ||

| Pentecostal | 107 | 0.9% | 174.6 | 1.4% | 219.6 | 1.7% | 260,560 | 2.1% | ||

| Presbyterian and Reformed Churches | 560 | 4.9% | 675.5 | 5.4% | 596.7 | 4.7% | 524,338 | 4.3% | ||

| Salvation Army | 77.8 | 0.7% | 74.1 | 0.6% | 64.2 | 0.5% | 48,939 | 0.4% | ||

| Seventh-day Adventist | 48 | 0.4% | 52.7 | 0.4% | 55.3 | 0.4% | 62,945 | 0.5% | ||

| Uniting Church | 1182.3 | 10.4% | 1334.9 | 10.6% | 1135.4 | 9.0% | 870,183 | 3.7% | ||

| Other Christianity (defined and not defined) | 596 | 5.2% | 322.7 | 2.6% | 468.6 | 3.7% | 768,649 | 6.3% | ||

| Christian total | 11,381.9 | 100% | 12,582.9 | 100% | 12,685.9 | 100% | 12,201,600 | 100% | ||

| State | 2001 census | 2006 census | 2011 census | 2016 census | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christians (000's) | % population | Christians (000's) | % population | Christians (000's) | % population | Christians (000's) | % population | |

| 4,520.3 | 71.4% | 4,434.7 | 67.7% | 4,462.2 | 64.5% | 4,127.8 | 55.2% | |

| 3,011.3 | 64.6% | 2,985.8 | 60.5% | 3,078.1 | 57.5% | 2,839.4 | 47.9% | |

| 2,499.3 | 70.9% | 2,589.5 | 66.3% | 2,785.0 | 64.3% | 2,635.5 | 56.0% | |

| 1,157.1 | 63.2% | 1,162.5 | 59.3% | 1,300.4 | 58.1% | 1,231.2 | 49.8% | |

| 942.9 | 64.1% | 906.1 | 59.8% | 914.4 | 57.3% | 823.6 | 49.1% | |

| 320.2 | 69.4% | 306.1 | 64.2% | 295.4 | 59.6% | 253.5 | 49.7% | |

| 198.5 | 64.0% | 195.2 | 60.2% | 197.1 | 55.2% | 180.3 | 45.4% | |

| 114.0 | 60.6% | 105.4 | 54.6% | 117.6 | 55.5% | 109.1 | 47.7% | |

| All Australia | 12,764.3 | 68.0% | 12,685.8 | 63.9% | 13,150.1 | 61.1% | 12,202.6 | 52.1% |

Church attendance

While church affiliation as reported in the census identifies the largest denominations, there is no overarching study that shows how active the members are. Some smaller studies include the National Church Life Survey which researches weekly church attendance among other items through a survey done in over 7000 congregations in many but not all Christian denominations every Australian Census year and from that estimates figures for those denominations nationally.[129]

From the survey about 8.8% of the Australian population attended a church in one of the covered denominations in a given week in 2001. The Catholic Church represents the highest number of church attenders, with over 50 percent. Whilst church attendance is generally decreasing the Catholic Church attendance in Australia is declining at a rate of 13 percent.[129] Pentecostal denominations such as Australian Christian Churches (formerly Assemblies of God) and Christian City Churches continue to grow rapidly, growing by over 20 per cent between 1991 and 1996. Some Protestant denominations such as the Baptist Union of Australia and the Churches of Christ in Australia grew at a smaller rate, less than 10 per cent, between 1991 and 1996.[129] McCrindle Research has found that Pentecostals grew to a larger denomination (12%) than Anglicans (11%) in 2014.[130] Roy Morgan Research has found in a survey of 4840 Australians between October and December 2013 that 52.6% of Australians were Christian, while 37.6% had no religion.[131]

| Denomination | 2001 est. wkly att. ('000) | % total att. | % change since 1996 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anglican | 177.7 | 11.7% | −2% |

| Apostolic | 9.1 | 0.6% | 20% |

| Assemblies of God | 104.6 | 6.9% | 20% |

| Baptist | 112.2 | 7.4% | 8% |

| Bethesda Ministries | 2.7 | 0.2% | na |

| Christian & Missionary Alliance | 4.1 | 0.3% | na |

| Christian City Churches | 11.4 | 0.7% | 42% |

| Christian Revival Crusade | 11.4 | 0.7% | −7% |

| Church of the Nazarene | 1.6 | 0.1% | 33% |

| Churches of Christ | 45.1 | 3.0% | 7% |

| Lutheran | 40.5 | 2.7% | −8% |

| Presbyterian | 35.0 | 2.3% | −3% |

| Reformed | 7.1 | 0.5% | −1% |

| Salvation Army | 27.9 | 1.8% | −7% |

| Seventh-day Adventist | 36.6 | 2.4% | na |

| Uniting | 126.6 | 8.3% | −11% |

| Vineyard | 2.5 | 0.2% | −17% |

| Wesleyan Methodist | 3.8 | 0.2% | −7% |

| Catholic | 764.8 | 50.2% | −13% |

| Total Attendance | 1,524.7 | 100.0% | -7% |

"Bible Belts"

In Australia, the term "Bible Belt" has been used to refer to areas within individual cities and some regions of states such as Queensland, which have a high concentration of Christians, usually centralised around a megachurch, for example:[132]

- the north-western suburbs of Sydney focusing on The Hills District, where Hillsong Church is located

- the north-eastern suburbs of Adelaide focusing on Paradise, Modbury and Golden Grove, where Influencers Church is located

- the south-eastern region of Queensland comprising the towns of Laidley, Gatton and Toowoomba.

- the Brisbane southern suburbs of Mansfield, Springwood, Carindale and Mount Gravatt. Garden City Assembly of God church, Citipointe church, George Salloum's The 'Christian' Church, and Brisbane Hillsong are notable mega-churches in this area.

Toowoomba

Toowoomba city in Queensland has long been regarded as fertile ground for biblical literalism, particularly for those within the Pentecostal and charismatic stream of Christianity. This was exemplified by the highly publicised rise and subsequent fall of Howard Carter[133] and the Logos Foundation in the 1980s.[134] Pentecostal churches within the city have, since that time, banded together into a loose federation known as the Toowoomba Christian Leaders' Network.[135] This network, views itself as having a divine mission to 'take the city for the Lord' and as such, endorses elements of religious right-wing political advocacy.[136]

The Toowoomba Christian Fellowship, has in recent times attracted publicity for the cult-like manner in which it operates.[137] It will possibly become one of the largest mega-churches in Australia.[138]

The Range Christian Fellowship in Blake Street Toowoomba, originally formed with 300 adherents in 1997 as a protest to the acceptance of homosexuality, has become known for bizarre manifestations and phenomena associated with the Toronto blessing and the North American movements mentioned above. This has included squealing, holy laughter, an inability to stand or sit, retching as though experiencing child-birth, moments of religious ecstasy and emotional euphoria, uttering apocalyptic prophecies and the use of textile banners that are believed to have special powers emanating from divinely inspired designs.[139] Some former adherents of this church, who have regarded themselves as spiritually elite, have at times displayed cultish tendencies. Like other similar churches in Toowoomba, the Range Christian Fellowship became strongly influenced by end-times conspiracy prophecies associated with Y2K, when members of this church purchased generators, engaged in significant food hoarding, took lessons in self-sufficiency and planned for a total collapse of modern society. In the period following this, some church members displayed obsessive and highly superstitious behavior in regard to the Prayer of Jabez doctrine.[140]

Revival Ministries of Australia Shiloh Centre in Russel Street, has a sole focus on the concept of revivalism, founded on precepts of spiritual warfare Christianity and a belief in a providential purpose for the city of Toowoomba as a hub of religious revival.[141] This church was formed following a schism with the Range Christian Fellowship and has carried with it some, but not all, of the bizarre manifestations of religious ecstasy associated with that congregation. Many of its members were religiously active during the years roughly covering 1989 through till the late 1990s, as part of the now defunct Rangeville Uniting Church Toowoomba,[142] where they, along with other local Pentecostal church leaders and their followers, engaged in significant strategic-level Spiritual Warfare.

- They still claim that through this action they took control of the demonic Territorial Spirits (evil spirits) that were making the city both sinful and resistant to the gospel message. Following this, it was expected and predicted (at times through prophecies) that a great revival of Christian faith including thousands of new conversions would follow, in addition to a reduced crime rate, phenomenal church growth, improved morality, general prosperity among the population and the installation of men and women of God into government. There were further claims that this action had placed Toowoomba strategically to be a hub of the anticipated great Australian revival. This expectation of a citywide transformation failed to materialize and was based on the teaching of North American Christian-mystic preacher George Otis jnr., whose claims of great transformations in several South American locations are now regarded as false, as they have been unable to be verified when investigated by his critics.[143]

Christianity and the wider culture

Christianity held strong influence in Australia society after British colonisation, but the influence of Christianity declined in the latter part of the 20th century.

Marriage

The Anglican Church has said that churches are being sidelined in the wider debate on same-sex marriage.[144]

The ACT Attorney-General, Simon Corbell has said, in the ACT, it will be, "unlawful for those who provide goods, services and facilities in the wedding industry to discriminate against another person on the basis of their sexuality or their relationship status. This includes discrimination by refusing to provide or make available those goods, services or facilities."[145] During the short time that same-sex marriages took place in ACT a Uniting Church minister sought and acquired permission to perform same sex marriages.[146]

Media

Liberal senator Eric Abetz has said that media felt comfortable vilifying Christian politicians. Conservative politicians are often described as being "extreme" or from the "Religious Right". He said that the Canberra press gallery gives, "more positive coverage to politicians and policies they agreed with".[147]

Schools

The Anglican Church has criticised the Victorian government for cutting religious education in state schools.[144]

Some Christians have criticised the Safe Schools program[148] (which is used in 400 primary and secondary schools)[149][150] as "radical sexual experimentation".[151] The program includes information about human sexuality and sexual orientations, as well as gender identity.

Life issues

Some Christians have objected to proposals to establish buffer zones around abortion clinics in both Victoria[152] and Tasmania saying they limit the freedom to protest.[153]

Adoption

Adoption is currently restricted in Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and Northern Territory to couples of the opposite sex. The Victorian government has drafted adoption legislation for same-sex parents which does not include any exemptions for faith-based adoption agencies. New South Wales adoption legislation grants these exemptions.[154][155] The proposed Victorian legislation has been described as "social engineering" which will impact on principles of faith and conscience for religious believers.[156]

References

- "Census TableBuilder - Dataset: 2016 Census - Cultural Diversity". Australian Bureau of Statistics – Census 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- A list of Influential Australian Christians, 2011, archived from the original on 7 January 2011, retrieved 4 November 2011

- "Cultural diversity". 1301.0 – Year Book Australia, 2008. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2008-02-07. Archived from the original on 2012-05-31. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- Manning Clark; A Short History of Australia; Penguin Books; 2006; pp. 5–6

- "Biography – Pedro Fernandez de Quiros – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adb.online.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "South Land to New Holland | National Library of Australia". Nla.gov.au. Archived from the original on 6 September 2006. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Biography – Luis Vaez de Torres – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- Johnson, Richard (1753? – 1827) Biographical Entry – Australian Dictionary of Biography Online Archived April 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Manning Clark; A Short History of Australia; Penguin Books; 2006; pp. 13–14

- Manning Clark; A Short History of Australia; Penguin Books; 2006; p. 18

- Marsden, Samuel (1765–1838) Biographical Entry – Australian Dictionary of Biography Online Archived April 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Australia Archived December 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Catholic Australia – The Catholic Community in Australia Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Catholic History of Australia: Botany Bay Story". Saint Anne's Home Schooling Group. Archived from the original on 18 September 2008.

- Nairn, Bede. "Biography – John Bede Polding – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- Iltis, Judith. "Biography – Caroline Chisholm – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Sisters of Charity Australia homepage". Archived from the original on 1 October 2009.

- "St Vincent's Hospital, history and tradition, sesquicentenary – sth.stvincents.com.au". Stvincents.com.au. Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Sisters of The Good Samaritans". Goodsams.org.au. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- O’Kelly SJ, AM, Fr Greg. "History of the Jesuits in Australia". Archived from the original on 29 August 2007.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- A. E. Cahill (1911-08-16). "Biography – Patrick Francis Moran – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 28 April 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- Apsa2000.anu.edu.au Archived May 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Coming to Australia". mercy.org.au. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- "Marist History". parramarist.nsw.edu.au. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- Thorpe, Osmund. "Biography – Mary Helen MacKillop – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "125 Years in Australia " Our History " About Us". salvos.org.au. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Did You Know? " Overview " About Us". salvos.org.au. 14 January 2005. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Banks and telcos biggest losers of the public's trust". www.smh.com.au. 2009-11-20. Archived from the original on 2016-01-15. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- Hazell, George. "Biography – George Lyndon Carpenter – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Eva Burrows – Biographical Information". Australianbiography.gov.au. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Commonwealth Of Australia Constitution Act, Chapter V. The States". Commonwealth of Australia. Archived from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- Frame, Tom. "A History of Anglicanism". Archived from the original on 9 March 2010.

- "Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia — History". Greekorthodox.org.au. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- Learning & Teaching @ UNSW Archived April 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "The Journey of the Catholic Church in Australia". Catholic Enquiry Centre. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008.

- "To Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders of Australia in Alice Spring (November 29, 1986) | John Paul II". Vatican.va. 1986-11-29. Archived from the original on 2014-02-15. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "The Sydney Morning Herald: national, world, business, entertainment, sport and technology news from Australia's leading newspaper". Smh.com.au. Archived from the original on 2016-01-15. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 24, 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Randwick's turf survives WYD Archived July 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Perry, Michael (20 July 2008). "FACTBOX: World Youth Day final Mass facts and figures". Reuters.

- World Youth Day 2008 – Catholic Online Archived January 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- World Youth Day a logistical success Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11: 14. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Mundine, Graeme (17 April 2005). "Pope John Paul II's Indigenous legacy". European Network for Indigenous Australian Rights (ENIAR). Archived from the original on 1 July 2005. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- "Reconciliation and other Indigenous Issues". Anglican Church of Australia. Archived from the original on 16 June 2005.

- "Reconciliation Australia". Reconciliation.org.au. 2015-09-10. Archived from the original on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Aboriginal involvement with the Church". City of Sydney website. Archived from the original on 22 April 2002.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 7, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The 7.30 Report". ABC. 2010-03-25. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Nocookies". The Australian. Archived from the original on 2010-12-02. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "The Coming of the Light Festival". Torres Strait Regional Authority. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007.

- "Influential Australian Aboriginal Christians". Archived from the original on 2019-08-20. Retrieved 2019-08-20.

- "Our History". Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010.

- "A father to the poor and dispossessed". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 May 2005. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Australia". Sosj.org.au. Archived from the original on 2011-02-18. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Home". Natsicc.org.au. Archived from the original on 2016-03-26. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Chisholm's supporters push for sainthood". The Age. Melbourne. 24 October 2007. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- "Opening Mass underway". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 July 2008. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "Catholic Health Australia". Archived from the original on 2016-06-02.

- "Sisters of Charity Health Service, History". St. Vincent'a Health, Australia. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "Facility heritage | Heritage | About Us | St Vincent's Hospital Sydney". Exwwwsvh.stvincents.com.au. Archived from the original on 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- by admin (2016-02-07). "The best lipo suction and breast implants". LCMHealthcare. Archived from the original on 2016-01-12. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Site Title – Home". Littlesistersofthepoor.org.au. Archived from the original on 2018-08-25. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "ADRA website, homepage". Archived from the original on 2016-04-03. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "RFDS, History". Royal Flying Doctor Service. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "A Snapshot of Schools in Australia 2013" (PDF). McCrindle Research. 15 March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- "4102.0 – Australian Social Trends, 2006". Abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Adventist Schools Australia – Home". Asa.adventistconnect.org. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Blessed Mary MacKillop: Beginnings". Archived from the original on 23 March 2010.

- "Our History". Australian Catholic University (ACU) National. Archived from the original on 29 March 2009.

- "The University of Notre Dame Australia website". Archived from the original on 21 March 2012.

- by T. L. Suttor. "Biography – William Bernard Ullathorne – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2011-04-08. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- by A. E. Cahill (1911-08-16). "Biography – Patrick Francis Moran – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adb.online.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- Griffin, James. "Biography – Daniel Mannix – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2011-04-10. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- Jones, Philip. "Biography – David Unaipon – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2011-04-13. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Civics | Sir Douglas Nicholls". Curriculum.edu.au. 2005-06-14. Archived from the original on 2016-06-03. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "The voluble and the Word: amen to that". The Sydney Morning Herald. 10 October 2009. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Morris, Linda (11 October 2005). "Churches against changes". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- Lateline – 28/1/2002: Labor rethinks detention stance Archived July 31, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Australian Broadcasting Corp.

- About us. "Our CEO – Tim Costello | World Vision Australia". Worldvision.com.au. Archived from the original on 2015-05-11. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Nocookies". The Australian. Archived from the original on 2011-01-20. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Before office – Robert Hawke – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2016-05-12. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Before office – Paul Keating – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2016-05-12. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Howard, Rudd woo Christians online – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. 2007-08-10. Archived from the original on 2011-03-16. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 8, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Easterfest Archived February 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 16, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Ulladulla Blessing of The Fleet Festival". Blessingofthefleet.info. Archived from the original on 2016-04-30. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Heritage | NSW Environment & Heritage". Heritage.nsw.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2012-06-14. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- D. I. McDonald. "Wardell, William Wilkinson (1823–1899)". Biography – William Wilkinson Wardell – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adb.online.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 2016-05-07.