Chernyakhov culture

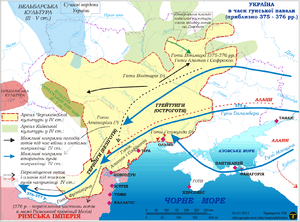

The Chernyakhov culture, or Sântana de Mureș culture,[1][2][3] is an archaeological culture that flourished between the 2nd and 5th centuries AD in a wide area of Eastern Europe, specifically in what is now Ukraine, Romania, Moldova and parts of Belarus. The culture is thought to be the result of a multiethnic cultural mix of the Sarmatian, Slavic, Gothic, and Geto-Dacian (including Romanised Daco-Romans) populations of the area.[4][5]

The Chernyakhov culture territorially replaced its predecessor, the Zarubintsy culture. Both cultures were discovered by the Czech-Ukrainian archaeologist, Vikentiy Khvoyka, who conducted numerous excavations around Kiev and its vicinity. Among other archaeologists are Austrian Karel Hadáček from Eastern Galicia and Ivan Kovac from Transylvania. With the invasion of Huns, the culture declined and was replaced with the Penkovka culture (or the culture of the Antes).

The Chernyakhov culture is very similar to the Wielbark culture, which was located closer to the Baltic Sea.

Location and nomenclature

The Chernyakhov culture encompassed regions of modern Ukraine, Moldova, and Romania.[6] It is named after the localities Sântana de Mureș, Mureș County, Transylvania in Romania and Cherniakhiv, Kaharlyk Raion, Kyiv Oblast in Ukraine. The dual name reflects past preferential use by different schools of history (Romanian and Soviet) to designate the culture.

The spelling "Chernyakhov" is the transliteration from the Russian language. Other spellings include Marosszentanna (Hungarian), Sîntana de Mureș (pre-1993 Romanian spelling), Cherniakhiv (Ukrainian), Czerniachów (Polish), and several others.

Origins

Archaeology, identity and ethnicity

The 'culture-historical' doctrine founded by German archaeologist Gustaf Kossinna, assumed that “sharply defined archaeological culture areas correspond unquestionably with the areas of particular peoples or tribes”.[7] Scholars today are more inclined to see material cultures as cultural-economic systems incorporating many different groups. "What created the boundaries of these cultural areas were not the political frontiers of a particular people, but the geographical limits within which the population groups interacted with sufficient intensity to make some or all of the remains of their physical culture – pottery, metal work, building styles, burial goods and so on- look very similar.[8]

Kossinna's Siedlungsarchäologie ('settlement archaeology') postulated that materially homogeneous archeological cultures could be matched with the ethnic groups defined by philologists.

— Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars, p. 61

Essentially, scholars are tentative in ascribing an 'ethnic' identity to the material remains of past populations, although they recognise that certain objects may have been manipulated to represent some form of group identity, especially at times of inter-group conflict.

Early 20th century views

In the earlier half of the 20th century, scholars spent much energy debating the ethnic affinity of people in the Chernyakov zone. Soviet scholars, such as Boris Rybakov, saw it as the archaeological reflection of the Proto-Slavs,[9] but western, especially German, historians, and Polish archeologists attributed it to the Goths. According to Kazimierz Godłowski (1979), the origins of Slavic culture should be connected with the areas of the upper Dnieper basin (the Kiev culture) while the Chernyakhov culture with the federation of the Goths.[10] However, the remains of archaeologically visible material culture and their link with ethnic identity are not as clear as originally thought.

The migration theory from Scandinavia to the Polish Baltic coast regions and further on to Ukraine was ideal propaganda material for German Nazi Ostsiedlung ideology and arguments for Lebensraum. Reference material used during that era was Ludwig Schmidt's Geschichte der deutschen Stämme (History of the German Tribes)[2]

Modern research

Today, scholars recognize the Chernyakov zone as representing a cultural interaction of a diversity of peoples, but predominantly those who already existed in the region,[11] whether it be the Sarmatians,[12] or the Getae-Dacians (some authors believe that the Getae-Dacians played the leading role in the creation of the culture).[13] Late Antiquity authors often confused the Getae with the Goths, most notably Jordanes, in his Getica.

Finds

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Ukraine |

|

|

Early history

|

|

Modern history

|

|

Topics by history |

|

|

Funerary rites

Both inhumation and cremation were practiced. The dead were buried with grave goods – pottery, iron implements, bone combs, personal ornaments, although in later periods grave goods decrease. Of the inhumation burials, the dead were usually buried in a north–south axis (with head to north), although a minority are in east–west orientation. Funerary gifts often include fibulae, belt buckles, bone combs, glass drinking vessels and other jewelry. Women's burials in particular shared very close similarities with Wielbark forms - buried with two fibulae, one on each shoulder. Like in the Wielbark culture, Chernyakhov burials usually lack weapons as funerary gifts, except in a few cremation burials reminiscent of Przeworsk influences.[14] Although cremation burials are traditionally associated with Dacian, Germanic and Slavic peoples, and inhumation is suggestive of nomadic practice, careful analysis suggests that the mixed burials were of an earlier period, whilst toward the end there was a trend toward inhumation burials without grave goods. This could be the result of the influences of Christianity, but could just as easily be explained in terms of an evolution of non-Christian beliefs about the afterlife.

Ceramic wares

Pottery was predominantly of local production, being both wheel and hand-made. Wheel made pottery predominated, and was made of finer clay. It was reminiscent of earlier Sarmatian types, refined by Roman and La Tene influences. Hand made pottery showed a greater variety in form, and was sometimes decorated with incised linear motifs. In addition, Roman amphorae are also found, suggesting trade contacts with the Roman world. There is also a small, but regular, presence of distinct hand–made pottery typical of that found in western Germanic groups, suggesting the presence of Germanic groups.

Economy

The Chernyakhov people were primarily a settled population involved in cultivation of cereals – especially wheat, barley and millet. Finds of ploughshares, sickles and scythes have been frequent. Cattle breeding was the primary mode of animal husbandry, and the breeding of horses appears to have been restricted to the open steppe. Metalworking skills were widespread throughout the culture, and local smiths produced much of the implements, although there is some evidence of production specialization.

Decline

The Chernyakhov culture ends in the 5th century, attributed to the arrival of the Huns.[12] The collapse of the culture is no longer explained in terms of population displacement, although there was an outmigration of Goths. Rather, more recent theories explain the collapse of the Chernyakhov culture in terms of a disruption of the hierarchical political structure that maintained it. John Mathews suggests that, despite its cultural homogeneity, a sense of ethnic distinction was kept between the disparate peoples. Some of the autochthonous elements persist,[15] and become even more widespread, after the demise of the Gothic elite – a phenomenon associated with the rise and expansion of the early Slavs.

Migration and diffusion theories

Migration

Whilst acknowledging the mixed origins of the Chernyakiv culture, Peter Heather suggests that the culture is ultimately a reflection of the Goths' domination of the Pontic area. He cites literary sources that attest that the Goths were the centre of political attention at this time.[16] In particular, the culture's development corresponds well with Jordanes' tale of Gothic migration from Gothiscandza to Oium, under the leadership of Filimer. Moreover, he highlights that crucial external influences that catalysed Chernyakhov cultural development derived from the Wielbark culture. Originating in the mid-1st century, it spread from south of the Baltic Sea (from territory around later Pomerania) down the Vistula in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. Wielbark elements are prominent in the Chernyakhov zone, such as typical 'Germanic' pottery, brooch types and female costume, and, in particular, weaponless bi-ritual burials. Although cultures may spread without substantial population movements, Heather draws attention to a decrease in the number of settlements in the original Pomeranian Wielbark heartland as evidence of a significant population movement. Combined with Jordanes' account, Heather concludes that a movement of Goths (and other east Germanic groups such as Heruli and Gepids) "played a major role in the creation of the Cernjachove culture".[17] He clarifies that this movement was not a single, royal-led, migration, but was rather accomplished by a series of small, sometimes mutually antagonistic groups.[18]

Diffusion

However, Guy Halsall challenges some of Heather's conclusions. He sees no chronological development from the Wielbark to Chernyakhov culture, given that the latter stage of the Wielbark culture is synchronous with Chernyakhov, and the two regions have minimal territorial overlap. "Although it is often claimed that Cernjachov metalwork derives from Wielbark types, close examination reveals no more than a few types with general similarities to Wielbark types".[19] Michael Kulikowski also challenges the Wielbark connection, highlighting that the greatest reason for Wielbark-Chernyakhov connection derives from a "negative characteristic" (i.e., the absence of weapons in burials), which is less convincing proof than a positive one. He argues that the Chernyakhov culture could just as likely have been an indigenous development of local Pontic, Carpic or Dacian cultures, or a blended culture resulting from Przeworsk and steppe interactions. Furthermore, he altogether denies the existence of Goths prior to the 3rd century. Kulikowski states that no Gothic people, nor even a noble kernel, migrated from Scandinavia or the Baltic. Rather, he suggests that the "Goths" formed in situ. Like the Alemanni or the Franks, the Goths were a "product of the Roman frontier".[20]

Other influences, such as a minority of burials containing weapons, are seen from the Przeworsk and Zarubinec cultures. The latter has been connected with early Slavs.[12]

Genetics

In 2019, a genetic study of various cultures of the Eurasian Steppe, including the Chernyakhov culture, was published in Current Biology. Samples from three individuals thought to belong its Gothic component were analyzed. Compared to earlier samples from the region, attributed to Scythians and Sarmatians, the results appeared to confirm that the Chernyakhov culture emerged partly as a result of a new non-Scythian population, with a higher amount of Near Eastern ancestry. These results appeared to confirm the theory that the Chernyakhov culture emerged as a result of migrations from the direction of central Europe.[21]

See also

Notes

- Halsall 2007.

- Kulikowski 2007.

- Matthews & Heather 1991, p. 47.

- Eiddon, Edwards & Heather 1998, p. 488: "In the past, the association of this [Černjachov] culture with the Goths was highly contentious, but important methodological advances have made it irresistible."

- Matthews & Heather 1991, p. 88-92.

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 104.

- Curta 2001, p. 24. Citing Kossinna 1911, p. 3

- Heather 2006.

- Barford 2001, p. 40.

- Buko 2008, p. 58.

- Halsall 2007, p. 132: "The Cernjachov culture is a mixture of all sorts of influences, but most come from existing cultures in the region"

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 106.

- Matthews & Heather 1991, p. 90.

- Heather 1998, p. 47.

- Matthews & Heather 1991, p. 91: "settlement was continuous from the period of the Sintana de Mures/ Cernjachov Culture right through the Migration Period into the Middle Ages proper"

- Matthews & Heather 1991.

- Heather 1998, pp. 22, 23.

- Heather 1998, pp. 43, 44.

- Halsall 2007, p. 133.

- Kulikowski 2007, pp. 60–68.

- Järve 2019.

References

- Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 1-884964-98-2

- Heather, Peter (2006), The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-515954-3

- Eiddon, Iorwerth; Edwards, Stephen; Heather, Peter (1998), "Goths & Huns", The Late Empire, The Cambridge Ancient History, 13, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30200-5

- Barford, Paul M (2001), The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe, Cornell University Press, ISBN 0-8014-3977-9

- Halsall, Guy (2007), Barbarian migrations and the Roman West, 376-568, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-43491-1

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139428880.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Järve, Mari (July 22, 2019). "Shifts in the Genetic Landscape of the Western Eurasian Steppe Associated with the Beginning and End of the Scythian Dominance". Current Biology. 29 (14): 2430–2441. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.019. PMID 31303491.

Genetic makeup agrees with the Gothic source of post- Scythian Chernyakhiv culture

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Kossinna, Gustaf (1911). Die Herkunft der Germanen: zur methode der Siedlungsarchäologie (in German). Würzburg: C. Kabitzsch.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Matthews, John; Heather, Peter (1991), The Goths in the fourth century, Liverpool University Press, ISBN 0-85323-426-4

- Heather, Peter J (1998), The Goths, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-20932-8

- Kulikowski, Michael (2007), Rome's Gothic Wars: from the third century to Alaric, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-84633-2

- Buko, Andrzej (2008), The Archeology of Early Medieval Poland. Discoveries-Hypotheses-Interpretations, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-16230-3

External links

- Slavs in Antiquity, summary in English translation of a text by Valentin V. Sedov, originally in Russian (V. V. Sedov: "Slavyane v drevnosti", Moscow 1994).