Bochasanwasi Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha

Bochasanwasi Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS) (IAST: Bocāsaṇvāsī Akṣhar Puruṣottam Swaminarayan Sansthā), is a Hindu denomination within the Swaminarayan Sampradaya.[1][2][3]:157 It was formed, by Yagnapurushdas (Shastriji Maharaj), on the principle that Swaminarayan was to remain present on earth through a lineage of gurus dating all the way back to Gunatitanand Swami – one of Swaminarayan's most prominent disciples.[4]:55[5][6] Based on the Akshar Purushottam doctrine (also known as Akshar-Purushottam Darshan), followers of BAPS believe Swaminarayan manifests through a lineage of Aksharbrahman Gurus[7], beginning with Gunatitanand Swami, followed by Bhagatji Maharaj, Shastriji Maharaj, Yogiji Maharaj, Pramukh Swami Maharaj, and presently Mahant Swami Maharaj. As of 2019, BAPS has 44 shikharbaddha mandirs and more than 1,200 mandirs worldwide that facilitate practice of this doctrine by allowing followers to offer devotion to the murtis of Swaminarayan, Gunatitanand Swami, and their successors.[8]:51 BAPS mandirs also feature activities to foster culture and youth development. Many devotees view the mandir as a place for transmission of Hindu values and their incorporation into daily routines, family life, and careers.[9]:418–422[10] BAPS also engages in a host of humanitarian and charitable endeavors through BAPS Charities, a separate non-profit aid organization which has spearheaded a number of projects around the world addressing healthcare, education, environmental causes, and community-building campaigns.[11]

BAPS Akshar Deri Logo | |

| |

| Abbreviation | BAPS |

|---|---|

| Motto | "In the joy of others lies our own." – Pramukh Swami Maharaj |

| Formation | 5 June 1907 |

| Founder | Shastriji Maharaj |

| Type | Religious organization |

| Headquarters | Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India |

| Location |

|

Area served | Worldwide |

| Leader | Mahant Swami Maharaj |

| Website | www www |

Mandirs

The mandir, known as a Hindu place of worship, serves as a hub for the spiritual, cultural, and humanitarian activities of BAPS. As of 2019, the organization has 44 shikharbaddha mandirs and more than 1,200 other mandirs spanning five continents.[12]:51 In the tradition of the Bhakti Movement, Swaminarayan and his spiritual successors began erecting mandirs to provide a means to uphold proper devotion to God on the path towards moksha, or ultimate liberation.[13]:440 BAPS mandirs thus facilitate devotional commitment to the Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, in which followers strive to reach the spiritually perfect state of Aksharbrahman, or the ideal devotee, thereby gaining the ability to properly worship Purushottam, the Supreme Godhead.[14]:7–13

Mandir rituals

The offering of bhakti, or devotion to God, remains at the center of mandir activities. In all BAPS Swaminarayan mandirs, murtis, or sacred images of Swaminarayan, Gunatitanand Swami, BAPS guru's and other deities, are enshrined in the inner sanctum. After completion of prana pratishta or life-force installation ceremonies, the deities are believed to reside in the murtis, and are thus subjects of direct worship through sacred daily rituals.[15]:240 In many mandirs, murtis are adorned with clothes and ornaments and devotees come to perform darshan, the act of worshiping the deity by viewing the sacred image.[15]:131, 140[16] Aarti, which is a ritual of waving lit lamps in circular motions to illuminate the different parts of the murti while singing a song of praise, is performed five times daily in shikharbaddha mandirs and twice daily in smaller mandirs. Additionally, food is offered to the murtis amidst the singing of devotional songs three times a day as part of the ritual of thaal, and the sanctified food is then distributed to devotees.[15]:140 Daily readings of and discourses on various Hindu scriptures also take place in the mandir.[15]:132 Many mandirs are also home to BAPS swamis, or monks.[15]:50 On weekends, assemblies are held in which swamis and devotees deliver discourses on a variety of spiritual topics. During these assemblies, bhakti is offered in the form of call-and-response hymns (kirtans) with traditional musical accompaniment. Religious assemblies also take place for children and teenagers of various age ranges.[15]:62 Throughout the year, mandirs celebrate traditional Hindu festivals. Assemblies with special discourses, kirtans, and other performances are arranged to commemorate Rama Navami, Janmashtami, Diwali, and other major Hindu holidays.[15]:138–147 Members of the sect are known as Satsangis. Male Satsangis are generally initiated by obtaining a kanthi at the hands of a swamis or senior male devotee while females receive the vartman from the senior women followers.[17]:273–276

Mandir activities

In addition to being focal points of religious activity, BAPS mandirs are also centers of culture.[14]:21 Many forms of traditional Indian art have their roots in Hindu scriptures and have been preserved and flourished in the setting of mandirs.[15]:220 Many BAPS mandirs outside of India hold Gujarati classes to facilitate scriptural study, instruction in traditional dance forms in preparation for performances in festival assemblies, and music classes where students are taught how to play traditional instruments such as tabla.[18][19] Devotees view the mandir as a place for transmission of knowledge of Hindu values and their incorporation into daily routines, family life, and careers.[20]:418–422[21]

Apart from classes teaching about religion and culture, mandirs are also the site of activities focused on youth development. Many centers organize college preparatory classes, leadership training seminars and workplace skills development workshops.[22][23][24] Centers often host women's conferences aimed at empowering women.[25] They also host sports tournaments and initiatives to promote healthy lifestyles among children and youth.[26] Many centers also host parenting seminars, marriage counseling, and events for family bonding.[27][28]

BAPS mandirs and cultural centers serve as hubs of several humanitarian activities powered by local volunteers. Mandirs in the US and UK host an annual walkathon to raise funds for local charities such as hospitals or schools.[29][30][31] Centers also host annual health fairs where needy members of the community can undergo health screenings and consultations.[32] During weekend assemblies, physicians are periodically invited to speak on various aspects of preventative medicine and to raise awareness on common conditions.[33] In times of disaster, centers closest to the affected area become hubs for relief activity ranging from providing meals to reconstructing communities.[34][35]

Notable mandirs

The founder of BAPS, Shastriji Maharaj, built the first mandir in Bochasan, Gujarat, which led the organization to be known as "Bochasanwasi" (of Bochasan).[14]:8–9

The organization's second mandir was built in Sarangpur, which also hosts a seminary for BAPS swamis.[15]:112

The mandir in Gondal was constructed around the Akshar Deri, the cremation memorial of Gunatitanand Swami, who is revered as a manifestation of Aksharbrahman.[15]:132

Shastriji Maharaj constructed his last mandir on the banks of the River Ghela in Gadhada, where Swaminarayan resided for the majority of his adult life.[15]:19[14]:9

Yogiji Maharaj constructed the mandir in the Shahibaug section of Ahmedabad, which remains the site of the international headquarters of the organization.[20]:86

Under the leadership of Pramukh Swami Maharaj, over 25 additional shikharbaddha mandirs have been built across Gujarat and other regions of India and abroad.

As a consequence of the Indian emigration patterns, mandirs have been constructed in Africa, Europe, North America, and the Asia-Pacific region.[14]:13–14 The BAPS mandir in Neasden, London was the first traditional Hindu mandir built in Europe.[14]:11–12 The organization has six shikharbaddha mandir's in North America in the metro areas of Houston, Chicago, Atlanta, Toronto, Los Angeles, and in the New Jersey suburb of Robbinsville Township, near Trenton, New Jersey.[36]

BAPS has constructed two large temple complexes dedicated to Swaminarayan called Swaminarayan Akshardham, in New Delhi and Gandhinagar, Gujarat, which in addition to a large stone-carved mandir has exhibitions that explain Hindu traditions and Swaminarayan history and values.[37]

BAPS is constructing a Hindu stone temple in the Middle East, in Abu Dhabi, the capital city of United Arab Emirates, on 55,000 square metres of land. Projected to be completed by 2021, and open to people of all religious backgrounds, the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi participated in the foundation stone-laying ceremony in the UAE, which is home to over three million people of Indian origin.[38]

History

Doctrinal origins (1799–1905)

Formation

The history of BAPS as an organization begins with Shastriji Maharaj's desire to propagate the mode of worship from Swaminarayan's teachings.[39] During Swaminarayan's own time, his group's spread had been curbed by opposition from Vaishnava sampradayas and others hostile to Swaminarayan's bhakti teachings.[14]:363 Due to the hostility of those who found Swaminarayan's growing popularity and teachings unacceptable, swamis and devotees during Swaminarayan's time tempered some of the public presentation of his doctrine, despite their own convictions, to mitigate violence towards their newly formed devotional community.[14]:364 The original doctrine taught by Swaminarayan continued to be conveyed in less public fora, but with the passage of time, Shastriji Maharaj sought to publicly reveal this doctrine, which asserted that Swaminarayan and his choicest devotee, Gunatitanand Swami, were ontologically, Purushottam and Akshar, respectively.[40]:186 However, when Shastriji Maharaj began openly discoursing about this doctrine, hereafter the Akshar-Purushottam doctrine, he was met with opposition from some quarters within the Vadtal diocese.[15]:55[14]:365 As the opposition against him grew violent,[14]:365 Shastriji Maharaj was left with no choice but to leave[15]:54–56 Vadtal to escape violent physical assaults.[14]:363–365 Thus, Williams notes, the very basis for separation from the Vadtal diocese and raison d’être for the formation of BAPS was this doctrinal issue.[15]:55[41][42]

Revelation of doctrine

Swaminarayan is viewed as God (Purushottam) by BAPS followers.[14]:362 Thus, his writings and discourses form the foundation for BAPS' theological tenets.[20]:342 Regarding Swaminarayan's philosophy, Akshar plays a fundamental role in the overall scheme of ultimate liberation.[40]:33 To that end, Swaminarayan indicated that those who wish to offer pure devotion to God (Purushottam)[14]:364 and are desirous of Moksha should imbibe the qualities of the Gunatit Guru[43] [Satsangijivanam Volume IV/72:1,2]. As Akshar, embodied as the Gunatit Guru,[44][45] epitomizes ideal devotion[15]:87 transcending maya. Swaminarayan's philosophical stand that liberation is unattainable unless one "identifies oneself with Akshar (a synonym of Brahman) and offers the highest devotion to Purushottam"[46] is also found in various Hindu scriptures [Mundaka Upanishad 3/2:9, Shrimad Bhagavatam I/1:1, Bhagvad Gita XVIII/54]. It follows that the doctrine that Shastriji Maharaj propagated, as Kim observes, "did not result in the rejection of any scriptures; instead, it was the beginning of a distinctive theology which added a single but powerful qualification, [that Akshar plays] in the form of the living guru".[20]:318

BAPS devotees also believe that Swaminarayan propagated the same doctrine through the mandirs he built.[14]:364 From 1822 to 1828, Swaminarayan constructed a total of six shikharbaddha mandirs in Gujarat; in each he installed the murtis of a principal deity coupled with their ideal devotee in the central shrine: Nar-Narayan-Dev in Ahmedabad (1822) and Bhuj (1823), Lakshmi-Narayan-Dev in Vadtal (1824), Madan-Mohan-Dev in Dholera (1826), Radha-Raman-Dev in Junagadh (1828), and Gopi-Nathji in Gadhada (1828).[14]:364–365

As Kim notes, "For BAPS devotees, the dual murtis in the original Swaminarayan temples imply that Swaminarayan did install a murti of himself alongside the murti of his ideal bhakta or Guru".[14]:364 Thus, Shastriji Maharaj, was simply extending that idea by enshrining the murti of Swaminarayan along with Gunatitanand Swami, his ideal devotee, in the central sanctum.[14]:364 However, many within the Vadtal and Ahmedabad dioceses did not subscribe to this view, and this became one of the main points of disagreement that led to the schism.[47]:55

Shastriji Maharaj explained that as per Swaminarayan's teachings, God desired to remain on earth through a succession of enlightened gurus.[48]:317 In many of his discourses in the Vachanamrut (Gadhada I-71,[49]:147–148 Gadhada III-26[49]:630–631 and Vadtal 5[49]:534) Swaminarayan explains that there forever exists a Gunatit Guru[14]:363 (perfect devotee) through whom Swaminarayan manifests on earth[47]:92 for the ultimate redemption of jivas.[40]:178

Shastriji Maharaj noted that Swaminarayan had "expressly designated" the Gunatit Guru to spiritually guide the satsang (spiritual fellowship) while instructing his nephews to help manage the administration of the fellowship within their respective dioceses.[48]:317[50]:610

Numerous historical accounts[40]:89[51] and texts[52] written during Swaminarayan and Gunatitanand Swami's time period identify Gunatitanand Swami as the embodiment of Akshar. Followers of BAPS believe that the Ekantik dharma that Swaminarayan desired to establish is embodied and propagated by the Ekantik Satpurush – the Gunatit Guru.[48]:327, 358 The first such guru in the lineage was Gunatitanand Swami.[15]:90 Shastriji Maharaj had understood from his own guru, Bhagatji Maharaj, that Gunatitanand Swami was the first Gunatit Guru in the lineage.[41]

Historically, each Gunatit Guru in the lineage has continued to reveal his successor; Gunatitanand Swami revealed Pragji Bhakta (Bhagatji Maharaj), who in turn revealed Shastriji Maharaj, who pointed to Yogiji Maharaj, who revealed Pramukh Swami Maharaj, the Guru, thus continuing the lineage of Akshar.[15]:89–90[41] Most recently, Pramukh Swami Maharaj revealed Mahant Swami Maharaj as the next and current Guru in the lineage.

Propagation of doctrine by Bhagatji Maharaj

Bhagatji Maharaj, born Pragji Bhakta, was originally a householder disciple of Gopalanand Swami. He was instructed to seek the company of Gunatitanand Swami if he desired to attain the gunatit state.[53][54] As he associated with Gunatitanand Swami, he began spending more time in Junagadh and obeyed every command from his new guru. He wanted to renounce the world and become an ascetic but he was told not to.[15]:56 Bhagatji Maharaj over time came to believe that the doctrine of Akshar-Purushottam was the true doctrine propagated by Swaminarayan.[55]

In 1883,[56][57] Shastriji Maharaj met Bhagatji Maharaj in Surat.[58] Recognizing Bhagatji Maharaj's spiritual caliber, Shastriji Maharaj began spending increasing amounts of time listening to Bhagatji Maharaj's discourses, and soon, he accepted Bhagatji Maharaj as his guru.[59]:21 Over time, Shastriji Maharaj also became a strong proponent of the Akshar-Purushottam Upasana.[15]:55 After Bhagatji Maharaj died on 7 November 1897,[60] Shastriji Maharaj became the primary proponent of the doctrine of Akshar-Purushottam.[15]:55 He believed that the construction of mandirs guided by this doctrine was urgently needed to facilitate followers' practice of this understanding of Swaminarayan devotion and identified Gunatitanand Swami and Bhagatji Maharaj as the first and second embodiments of Akshar.[14]:363

Schism and early foundational years (1905–1950)

In this regard, Shastriji Maharaj persuaded Acharya Kunjvihariprasadji to consecrate the murtis of Akshar (Gunatitanand Swami) and Purushottam (Swaminarayan) in the Vadhwan mandir.[59]:21 Shastriji Maharaj's identification of Gunatitanand Swami as the personal form of Akshar was already a paradigm shift for some that led to "opposition and hostility"[14]:363 from many within the Vadtal diocese.[14]:357–390 Moreover, the installation of Gunatitanand Swami's murti next to Swaminarayan in the Vadhwan Mandir, led to further hostility and opposition from many swamis of the Vadtal temple who were determined to prevent the murti of Gunatitanand Swami from being placed [along with Swaminarayan in the central shrine].[15]:55 Jaga Bhakta, a respected devotee of Gunatitanand Swami said: "It is the wish of Maharaj that the upasana (worship) of Akshar-Purushottam should be established. Therefore, you must take up this work. It shall be your shortcoming if you don't take a pledge to accomplish this task, and it shall be my shortcoming if I default in fulfilling it."

Following this, several attempts to murder him were made,[14]:365 but Shastriji Maharaj maintained his reluctance to leave Vadtal.[59]:21 Since Bhagatji Maharaj promised him, "Even if they cut you into pieces, I will stitch you together, but you must never leave the doors of Vadtal", Shastriji Maharaj refused to leave.[61] Seeing the unrelenting threat to Shastriji Maharaj's life, Krishnaji Ada, a respected devotee of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya, advised him to leave for his own safety, as per the teachings of Swaminarayan in the Shikshapatri Verse 153–154.[59]:21 Acknowledging the commands of Swaminarayan in the Shikshapatri, and interpreting Krishnaji Ada's words to be of Bhagatji Maharaj,[59]:21 Shastriji Maharaj decided to leave[47]:54–56 the Vadtal temple to preach in the surrounding regions until the temple became safe again.[59]:21

On 12 November 1905,[62]:Chp 5 – Pg 2 Shastriji Maharaj left the Vadtal temple with five swamis and the support of about 150 devotees.[63]:13 However, he did not want to believe that he was separating from Vadtal[64] as he initially instructed his followers to continue their financial contributions to and participation in the temples of the Vadtal diocese.[14]:365 (See Shastriji Maharaj: Formation of BAPS)

Mandirs to facilitate doctrinal practice

On 5 June 1907, Shastriji Maharaj consecrated the murtis of Swaminarayan and Gunatitanand Swami in the central shrine of the shikharbaddha mandir he was constructing

in the village of Bochasan in the Kheda District of Gujarat.[48]:91 This event was later seen to mark the formal establishment of the Bochasanwasi Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha,[14]:364 which was later abbreviated as BAPS. The Gujarati word Bochasanwasi implies hailing from Bochasan, since the organization's first mandir was built in this village.

Shastriji Maharaj continued to consolidate and spread the Akshar-Purushottam teachings of the nascent BAPS by spending the majority of 1908–15 discoursing throughout Gujarat, while continuing construction work of mandirs in Bochasan and Sarangpur. As recognition of Shastriji Maharaj's teachings continued to spread throughout Gujarat, he acquired a loyal and growing group of devotees, admirers, and supporters, many of whom were formerly associated with the Vadtal or Ahmedabad diocese of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya.[14]:365 Over the next four decades, Shastriji Maharaj completed four more shikharbaddha mandirs in Gujarat (Sarangpur – 1916, Gondal – 1934, Atladra – 1945, and Gadhada – 1951).[14]:365

Kim notes that these temples, in essence, represented the fundamental doctrine that Shastriji Maharaj wished to propagate based on Swaminarayan's teachings: "the ultimate reality [Purushottam] and the means, in the form of the Guru, which [enables a] devotee to offer eternal devotion to the ultimate reality".[14]:365 Thus, this historical period marked a "focused emphasis" on building shikharbaddha mandirs as a means of conveying Swaminarayan doctrine. Shashtriji Maharaj was accepted as the third successor, or Akshar by BAPS devotees.[65]

Successors

On 12 August 1910 Shastriji Maharaj met his eventual successor, Yogiji Maharaj, at the house of Jadavji in Bochasan.[63]:16 Yogiji Maharaj was a resident swami at Junagadh Mandir (Saurashtra),[40]:183 where Gunatitanand Swami had served as mahant.[63]:17 Yogiji Maharaj regarded Gunatitanand Swami as Akshar and also served the murti of Harikrishna Maharaj which had previously been worshiped by Gunatitanand Swami.[63]:17 As he already believed in the doctrine being preached by Shastriji Maharaj, Yogiji Maharaj left Junagadh on 9 July 1911 with six swamis to join Shastriji Maharaj's mission.[40]:186

On 7 November 1939, 17-year-old Shantilal Patel (who would become Pramukh Swami Maharaj) left his home[66] and was initiated by Shastriji Maharaj into the parshad order, as Shanti Bhagat, on 22 November 1939,[67] and into the swami order, as Narayanswarupdas Swami, on 10 January 1940.[67] Initially, he studied Sanskrit and Hindu scriptures[67] and served as Shastriji Maharaj's personal secretary. In 1946, he was appointed administrative head (Kothari) of the Sarangpur mandir.[67]

In the early part of 1950, Shastriji Maharaj wrote several letters to 28-year-old Shastri Narayanswarupdas expressing a wish to appoint him as the administrative president of the organization. Initially, Shastri Narayanswarupdas was reluctant to accept the position, citing his young age and lack of experience and suggesting that an elderly, experienced swami should take the responsibility.[68] However, Shastriji Maharaj insisted over several months, until, seeing the wish and insistence of his guru, Shastri Narayanswarupdas accepted the responsibility.[67] On 21 May 1950 at Ambli-Vali Pol in Amdavad, Shastriji Maharaj appointed Shastri Narayanswarupdas as the administrative president (Pramukh) of BAPS.[63]:11 He instructed Shastri Narayanswarupdas, who now began to be referred to as Pramukh Swami, to ennoble Satsang under the guidance of Yogiji Maharaj.[69]

In the last few years of his life, Shastriji Maharaj took steps to preserve the growth and future of BAPS by registering BAPS as a charitable trust in 1947 under India's new legal code.[63]:33

Development and organizational formation (1950–1971)

After the death of Shastriji Maharaj on 10 May 1951,[70] Yogiji Maharaj became the spiritual leader, or guru, of the organization while Pramukh Swami continued to oversee administrative matters as president of the organization.[15]:60 Yogiji Maharaj carried Shastriji Maharaj's mission of fostering the Akshar-Purushottam doctrine by building temples, touring villages, preaching overseas and initiating weekly local religious assemblies for children, youths and elders. In his 20 years as guru, from 1951 to 1971, he visited over 4,000 cities, towns and villages, consecrated over 60 mandirs and wrote over 545,000 letters to devotees.[63]:9

Youth Movement

This period of BAPS history saw an important expansion in youth activities. Yogiji Maharaj believed that in a time of profound and rapid social ferment, there was an imminent need to save the young from 'degeneration of moral, cultural and religious values'.[71]:219 To fill a void in spiritual activities for youths, Yogiji Maharaj started a regular Sunday gathering (Yuvak Mandal) of young men in Bombay[71]:217 in 1952.[63]:167 Brear notes, "His flair, dynamism and concern led within ten years to the establishment of many yuvak mandals of dedicated young men in Gujarat and East Africa".[71]:217 In addition to providing religious and spiritual guidance, Yogiji Maharaj encouraged youths to work hard and excel in their studies. Towards realizing such ideals, he would often remind them to stay away from worldly temptations.[72] A number of youths decided to take monastic vows.[40]:187 On 11 May 1961 during the Gadhada Kalash Mahotsav, he initiated 51 college-educated youths into the monastic order as swamis.[63]:168 Mahant Swami Maharaj initiated as Keshavjivandas Swami was one of the initiates.

East Africa

Satsang in Africa had started during Shastriji Maharaj's lifetime, as many devotees had migrated to Africa for economic reasons. One of Shastriji Maharaj's senior swamis, Nirgundas Swami, engaged in lengthy correspondence with these devotees, answering their questions and inspiring them to start satsang assemblies in Africa. Eventually, in 1928, Harman Patel took the murtis of Akshar-Purushottam Maharaj to East Africa and started a small center.[63]:20 Soon, the East Africa Satsang Mandal was established under the leadership of Harman Patel and Magan Patel.[63]:20

In 1955, Yogiji Maharaj embarked on his first foreign tour to East Africa.[71]:217[62]:Chp 5 – Pg 2 The prime reason for the visit was to consecrate Africa's first Akshar-Purushottam temple in Mombasa. The temple was inaugurated on 25 April 1955.[63]:168[73] He also travelled to Nairobi, Nakuru, Kisumu, Tororo, Jinja, Kampala, Mwanza and Dar es salaam.[63]:168 His travels inspired the local devotees to begin temple construction projects. Due to the visit, in a span of five years, the devotees in Uganda completed the construction of temples in Tororo, Jinja and Kampala and asked Yogiji Maharaj to revisit Uganda to install the murtis of Akshar-Purushottam Maharaj. The rapid temple constructions in Africa were helped by the presence of early immigrants, mainly Leva Patels, who came to work as masons, and were particularly skilled in temple building.[74]

As a result, Yogiji Maharaj made a second visit to East Africa in 1960 and consecrated hari mandirs in Kampala, Jinja and Tororo in Uganda.[63]:50 Despite his failing health, Yogiji Maharaj at the age of 78 undertook a third overseas tour of London and East Africa in 1970.[63]:169 Prior to his visit, the devotees had purchased the premises of the Indian Christian Union at Ngara, Kenya in 1966 and remodeled it to resemble a three-spired temple.[75] Yogiji Maharaj inaugurated the temple in Ngara, a suburb of Nairobi in 1970.[73][75]

England

In 1950, disciples Mahendra Patel and Purushottam Patel held small personal services at their homes in England. Mahendra Patel, a barrister by vocation, writes, "I landed in London in 1950 for further studies. Purushottambhai Patel...was residing in the county of Kent. His address was given to me by Yogiji Maharaj".[76] Beginning 1953, D. D. Meghani held assemblies in his office that brought together several followers in an organized setting. In 1958, leading devotees including Navin Swaminarayan, Praful Patel and Chatranjan Patel from India and East Africa began arriving to the UK.[76] They started weekly assemblies at Seymour Place every Saturday evening at a devotee's house.[76] In 1959, a formal constitution was drafted and the group registered as the "Swaminarayan Hindu Mission, London Fellowship Centre".[76] D.D. Megani served as Chairman, Mahendra Patel as Vice-Chairman and Praful Patel the secretary.[76] On Sunday, 14 June 1970, the first BAPS temple in England was opened at Islington by Yogiji Maharaj.[76] In this same year he established the Shree Swaminarayan Mission[40]:189 as a formal organization.[77]

United States

Yogiji Maharaj was unable to travel to the United States during his consecutive foreign tours. Nonetheless, he asked Dr. K.C. Patel, to begin satsang assemblies in the United States.[78] He gave Dr. Patel the names of twenty-eight satsangi students to help conduct [satsang] assemblies.[78]

In 1970, Yogiji Maharaj accepted the request of these students and sent four swami to visit the U.S.[78][79] The tour motivated followers to start satsang sabhas in their own homes every Sunday around the country.[78] Soon, K.C. Patel established a non-profit organization known as BSS under US law.[80] Thus, a fledgling satsang mandal formed in the United States before the death of Yogiji Maharaj in 1971.

Growth and further global expansion (1971–2016)

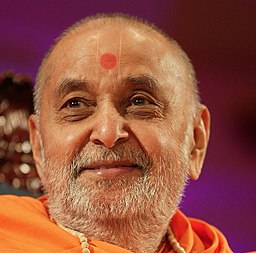

After Yogiji Maharaj's death, Pramukh Swami Maharaj became both the spiritual and administrative head of BAPS[81] in 1971.[82] He was the fifth spiritual guru of the BAPS organization.[83] Under his leadership, BAPS has grown into a global Hindu organization and has witnessed expansion in several areas. His work has been built on the foundations laid by his gurus – Shastriji Maharaj and Yogiji Maharaj.

Personal outreach (1971–1981)

Immediately upon taking helm, Pramukh Swami Maharaj ventured on a hectic spiritual tour in the first decade of his role as the new Spiritual Guru. Despite health conditions—cataract operation in 1980—he continued to make extensive tours to more than 4000 villages and towns, visiting over 67,000 homes and performing image installation ceremonies in 77 temples in this first decade.[15] He also embarked on a series of overseas tours beginning in 1974 as the guru. Subsequent tours were made in 1977, 1979, and 1980.[84]

Overall, he embarked on a total of 28 international spiritual tours between 1974 and 2014.[78][85] His travels were motivated by his desire to reach out to devotees for their spiritual uplift and to spread the teachings of Swaminarayan.[86]

Festivals and organization (1981–1992)

The personal outreach (vicharan) of the earlier era (1971–81) by Pramukh Swami Maharaj through traveling to villages and towns, writing letters to devotees, and giving discourses contributed to sustaining a global BAPS community.

The Gujarati migration patterns in the early 1970s, globalization factors and economic dynamics between India and the West saw the organization transform into a transnational devotional movement.[87] Organizational needs spanned from transmitting cultural identity through spiritual discourses to the newer much alienated generation in the new lands, temple upkeep and traveling to regional and local centers to disseminate spiritual knowledge. As a result, this era saw a significant rise in the number of swamis initiated to maintain the organizational needs of the community – both in India and abroad. Furthermore, having access to a greater volunteer force and community enabled the organization to celebrate festivals on a massive scale which marked the arrival of a number of milestone anniversaries in the history of the organization, including the bicentenary of Swaminarayan, bicentenary of Gunatitanand Swami, and the centenary of Yogiji Maharaj. Some effects of the celebration included a maturation of organizational capacity, increased commitment and skill of volunteers, and tangentially, an increased interest in the monastic path.

The Swaminarayan bicentenary celebration, a once in a life-time event for Swaminarayan followers, was held in Ahmedabad in April 1981.[15] On 7 March 1981, 207 youths were initiated into the monastic order.[15] In 1985 the bicentenary birth of Gunatitanand Swami was celebrated.[15] During this festival, 200 youths were initiated into the monastic order.[88]

The organization held Cultural Festivals of India in London in 1985 and New Jersey in 1991.[88] The month-long Cultural Festival of India was held at Alexandra Palace in London in 1985.[88] The same festival was shipped to US as a month-long Cultural Festival of India at Middlesex County College in Edison, New Jersey.[71]

Migrational patterns in the 70s led to a disproportionate number of Hindus in the diaspora.[87] Culturally, a need arose to celebrate special festivals (Cultural Festival of India) to reach out to youths in the diaspora to foster understanding and appreciation of their mother culture in a context accessible to them.[82][89] To engage the youths, festival grounds housed temporary exhibitions ranging from interactive media, dioramas, panoramic scenes and even 3D-exhibits.

By the end of the era, owing to the success of these festivals and the cultural impact it had on the youths, the organization saw a need to create a permanent exhibition in the Swaminarayan Akshardham (Gandhinagar) temple in 1991.

In 1992, a month-long festival was held to both celebrate Yogiji Maharaj's centenary and to inaugurate a permanent exhibition and temple called Swaminarayan Akshardham (Gandhinagar). The festival also saw 125 youths initiated into the monastic order bringing the total number of swamis initiated to more than 700 in fulfillment to a prophecy made by Yogiji Maharaj.[90]

Mandirs and global growth (1992–2016)

In the third leg of the era, the organization saw an unprecedented level of mandir construction activities taking place in order to accommodate the rapid rise of adherents across the global Indian diaspora. Initially, beginning with the inauguration of Swaminarayan Akshardham (Gandhinagar) in 1992. A number of shikharbaddha mandirs (large traditional stone mandirs) were inaugurated in major cities; Neasden (1995), Nairobi (1999), New Delhi (2004), Swaminarayan Akshardham (New Delhi) (2005), Houston (2004), Chicago (2004), Toronto (2007), Atlanta (2007), Los Angeles (2012), and Robbinsville (2014).

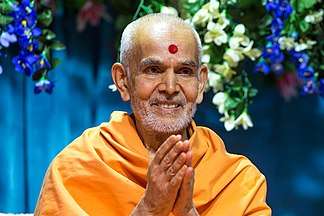

Mahant Swami Maharaj as Guru (2016 – present)

On 20 July 2012, in the presence of senior swamis in Ahmedabad, Pramukh Swami Maharaj revealed Keshavjivandas Swami (Mahant Swami) as his spiritual successor.[91]

Following the death of Pramukh Swami Maharaj on 13 August 2016, Mahant Swami Maharaj became the 6th guru and president of BAPS.[92] In 1961, he was ordained as a swami by Yogiji Maharaj and named Keshavjivandas Swami. Due to his appointment as the head (mahant) of the mandir in Mumbai, he became known as Mahant Swami.[93]

He continues the legacy of the Aksharbrahma Gurus by visiting BAPS mandirs worldwide, guiding spiritual aspirants, initiating devotees, ordaining swamis, creating and sustaining mandirs, and encouraging the development of scriptures.[12][94][95]

In his discourses, he mainly speaks on how one can attain God and peace through ridding one’s ego (nirmani), seeing divinity in all (divyabhav), not seeing, talking, or adapting any negative nature or behavior of others (no abhav-avgun), and keeping unity (samp).[96]

In 2017, he performed the ground-breaking ceremony for shikharbaddha mandirs in Johannesburg, South Africa, and Sydney, Australia, and in April 2019, he performed the ground-breaking ceremony for a traditional stone temple in Abu Dhabi.[12]

Philosophy

| Part of a series on | |

| Hindu philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orthodox | |

|

|

|

| Heterodox | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The philosophy of BAPS is centered on the doctrine of Akshar-Purshottam Darshan, in which followers worship Swaminarayan as God, or Purshottam, and his choicest devotee Gunatitanand Swami, as Akshar.[47]:73 The concept of Akshar has been interpreted differently by various branches of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya, and one major reason for the separation of BAPS from the Vadtal diocese has been attributed to doctrinal differences in the interpretation of the concept of Akshar.[47]:44 Both the Vadtal and Ahmedabad dioceses of the Swaminaryan Sampradaya believe Akshar to be the divine abode of the supreme entity Purushottam.[47]:73 The BAPS denomination concurs that Akshar is the divine abode of Purushottam, but they further understand Akshar as "an eternally existing spiritual reality having two forms, the impersonal and the personal"[47]:73[97][98]:158 Followers of BAPS identify various scriptures and documented statements of Swaminarayan as supporting this understanding of Akshar within the Akshar-Purushottam Darshan.[99]:95–103 BAPS teaches that the entity of Akshar remains on earth through a lineage of "perfect devotees", the gurus or spiritual teachers of the organization, who provide "authentication of office through Gunatitanand Swami and back to Swaminarayan himself."[15]:92 Followers hold Mahant Swami Maharaj[91] as the personified form of Akshar and the spiritual leader of BAPS.

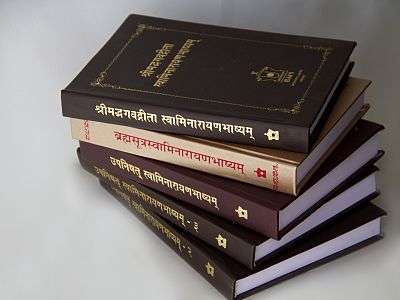

The Swaminarayan-Bhashyam is a published commentary written by Bhadreshdas Swami in 2007 that explicates the roots of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan in the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Brahma Sutras..[100][101] This is further corroborated in a classical Sanskrit treatise, also authored by Bhadreshdas Swami, called Swaminarayan-Siddhanta-Sudha.

Swaminarayan ontology

The Swaminarayan ontology comprises five eternal entities: jiva (jīva), ishwar (iśvara), maya (māyā), Aksharbrahman (Akṣarabrahman, also Akshara, Akṣara, or Brahman), Parabrahman (Parabrahman, or Purushottam, Puruṣottama).[98]:69 The entities are separate and distinct from one another and structured within a hierarchy.[102][98]:71–73 (refer to chart) Encompassing the entities of both Swaminarayan and his ideal devotee, this hierarchy emphasizes the relationship between Akshar and Purshottam.[48]:65

Parabrahman - At the top is Parabrahman. Parabrahman is the highest reality, God. He is understood as pragat (manifest on Earth), sakara (having a form), sarvopari (supreme), and karta (all do-er).[98]:75 He is also one and unparalleled, the reservoir for all forms of bliss and eternally divine. Parabrahman is also referred to as Purshottam and Paramatma, both of which reflect his supreme existential state.[48]:319 Furthermore, Parabrahman is the only unconditioned entity upon which the other four entities are contingent.[15]:78

Aksharbrahman - Subservient to Parabrahman is Aksharbrahman, also known as Akshara or Brahman, which exists simultaneously in four states.[98] :69,191 The first state is in the form of the impersonal chidakash, the divine, all-pervading substratum of the cosmos.[103][98]:191–192 Another form of Akshar is the divine abode of Parabrahman, known as Akshardham.[48]:319[98] :191,194 Muktas, or liberated jivas (souls), also dwell here in unfathomable bliss and luster which is beyond the scope of human imagination.[98]:194 The other two states of Akshar are personal, which manifest as the ideal servant of Purshottam, both within his divine abode of Akshardham and simultaneously on earth as the God-realized saint.[48]:320[98]:191

Maya - Below Aksharbrahman is maya.[98]:73 Maya utilizes three main qualities to create the physical world: sattva (goodness), rajas (passion), and tamas (darkness).[98]:246 Maya entangles ishwar and jiva and causes them to form an attachment to both their physical bodies and the material world.[48]:320[98]:245 This attachment denies them liberation, and only through contact with the personal form of Brahman can they overcome the illusion created by maya and attain liberation.[104]

Ishwar - Ishwars are conscious spiritual beings that are responsible for the creation, sustenance, and destruction of the cosmos, at the behest of Parabrahman.[48]:320[105] They are metaphysically higher than that of jivas yet are inferior to Parabrahman and Aksharbrahman.[98] :234 They are the deities that are above jiva, but are also bound by maya, and must transcend maya to attain final liberation.[106][98]:234–235

Jiva - Every living being can be categorized as a jiva. Jiva is derived from the Sanskrit verb-root 'jiv' which means to breathe or to live.[98]:211 In its pristine form, the jiva is pure and free from flaws, however the influence of maya propels the jiva through the cycles of births and deaths.[98]:211,218[48]:320–321[107]

Akshar-Purshottam Darshan

History

In 1907, Shastriji Maharaj consecrated the images of Akshar and Purshottam in a temple's central shrine in the village of Bochasan as sacred, marking the formation of the BAPS fellowship as a formally distinct organization.[15] However, the fundamental beliefs of the sampradaya date back to the time of Swaminarayan.[108] One revelation of Gunatitanand Swami as Akshar occurred in 1810 at the grand yagna of Dabhan, during which Swaminarayan initiated Gunatitanand Swami as a swami. On this occasion, Swaminarayan publicly confirmed that Gunatitanand Swami was the incarnation of Akshar, declaring, "Today, I am extremely happy to initiate Mulji Sharma. He is my divine abode – Akshardham, which is infinite and endless." The first Acharya of the Vadtal diocese, Raghuvirji Maharaj, recorded this declaration in his composition, the Harililakalpataru (7.17.49–50).[109] Under Shastriji Maharaj, considered the manifest form of Akshar at the time, the fellowship continued the traditions of the Akshar-Purshottam Darshan. He focused on the revelations of Gunatitanand Swami as Swaminaryan's divine abode and choicest devotee.[110]

Essence

The Akshar-Purushottam Darshan refers to two separate entities within the Swaminarayan ontology.[48]:65 These two entities are worshipped in conjunction by followers of BAPS in accordance with the instructions laid down in the Vachanamrut.[62]:Ch 5 - Pg 2 According to BAPS, Swaminarayan refers to Akshar in the Vachanamrut, with numerous appellations such as Sant, Satpurush, Bhakta and Swami, as having an august status that makes it an entity worth worshipping alongside God.[48]:453–455 For example, in Vachanamrut Gadhada I-37, Swaminarayan states: "In fact, the darshan of such a true Bhakta of God is equivalent to the darshan of God Himself"[111] Moreover, in Vachanamrut Vadtal 5, Swaminarayan states: Just as one performs the mãnsi puja of God, if one also performs the mãnsi puja of the ideal Bhakta along with God, by offering him the prasãd of God; and just as one prepares a thãl for God, similarly, if one also prepares a thãl for God's ideal Bhakta and serves it to him; and just as one donates five rupees to God, similarly, if one also donates money to the great Sant – then by performing with extreme affection such similar service of God and the Sant who possesses the highest qualities...he will become a devotee of the highest calibre in this very life.[112] Thus, in all BAPS mandirs the image of Akshar is placed in the central shrine and worshipped alongside the image of Purushottam.[15]:86[47]:112 Furthermore, BAPS believes that by understanding the greatness of God's choicest devotee, coupled with devotion and service to him and God, followers are able to grow spiritually. This practice is mentioned by Swaminarayan in Vachanamrut Vadtal 5: "by performing with extreme affection such similar service of God and the Sant who possesses the highest qualities, even if he is a devotee of the lowest type and was destined to become a devotee of the highest type after two lives, or after four lives, or after ten lives, or after 100 lives, he will become a devotee of the highest caliber in this very life. Such are the fruits of the similar service of God and God's Bhakta."[113]

Metaphysical ends

As per the Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, each jiva attains liberation and true realization through the manifest form of Akshar.[114] Jivas who perform devotion to this personal form of Brahman can, despite remaining ontologically different, attain a similar spiritual standing as Brahman and then go to Akshardham.[48]:319–320[115] It is only through the performance of devotion to Brahman that Parabrahman can be both realized and attained.[116]

Akshar as a living entity

According to the Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, the personal form of Akshar is forever present on the earth through a lineage of spiritual leaders, or gurus. It is through these gurus that Swaminarayan is also held to forever remain present on the earth.[15]:55 These gurus are also essential in illuminating the path that needs to be taken by the jivas that earnestly desire to be liberated from the cycle of rebirth.[48]:65 This lineage begins with Gunatitanand Swami (1785–1867), a swami who lived conterminously with Swaminarayan. Members of BAPS point to numerous historical anecdotes and scriptural references, particularly from the central Swaminarayan text known as the Vachanamrut, as veritable evidence that Gunatitanand Swami was the manifest form of Akshar.[48]:76 Swaminarayan refers to this concept specifically in Vachnamrut Gadhada I-21, Gadhada I-71, Gadhada III-26, Vadtal 5.[15]:92 Following Gunatitanand Swami, the lineage continued on through Bhagatji Maharaj (1829–1897), Shastriji Maharaj (1865–1951), Yogiji Maharaj (1892–1971), and Pramukh Swami Maharaj (1921–2016). Today Mahant Swami Maharaj is said to be the manifest form of Akshar.[91]

Swaminarayan praxis

According to BAPS doctrines, followers aim to attain a spiritual state similar to Brahman which is necessary for ultimate liberation.[48]:291 The practices of BAPS Swaminarayans are an idealistic "portrait of Hinduism."[48]:6 To become an ideal Hindu, followers must identify with Brahman, separate from the material body, and offer devotion to god[117][98]:276 It is understood that through association with Akshar, in the form of the God-realized guru, one is able to achieve this spiritual state.[48]:325 Followers live according to the spiritual guidance of the guru who is able to elevate the jiva to the state of Brahman.[48]:295 Thus devotees aim to follow the spiritual guidance of the manifest form of Akshar embedding the principles of righteousness (dharma), knowledge (gnan), detachment from material pleasures (vairagya) and devotion unto God (bhakti) in to their lives.[48]:358 The basic practices of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya are based on these four principles. Followers receive gnan through regularly listening to spiritual discourses and reading scriptures in an effort to gain knowledge of God and one's true self.[118] Dharma encompasses righteous conduct as prescribed by the scriptures.[118] The ideals of dharma range from practicing non-violence to avoiding meat, onions, garlic, and other items in their diet. Swaminarayan outlined the dharma of his devotees in the scripture the Shikshapatri.[48]:456[62]:Chp 5 – Pg 2 He included practical aspects of living life such as not committing adultery and respecting elders, gurus, and those of authority.[48]:333 Devotees develop detachment (vairagya) in order to spiritually elevate their soul (jiva) to a Brahmic state. This entails practices such as biweekly fasting (on the eleventh day of each half of each lunar month) and avoiding worldly pleasures by strongly attaching themselves to God.[48]:326 The fourth pillar, devotion (bhakti) is at the heart of the faith community. Common practices of devotion include daily prayers, offering prepared dishes (thal) to the image of God, mental worship of God and his ideal devotee, and singing religious hymns.[118] Spiritual service, or seva, is a form of devotion where devotees serve selflessly "while keeping only the Lord in mind."[48]:343

Followers participate in various socio-spiritual activities with the objective to earn the grace of the guru and thus attain association with God through voluntary service.[99]:97 These numerous activities stem directly from the ideals taught by Swaminarayan, to find spiritual devotion in the service of others.[48]:319–320, 389 By serving and volunteering in communities to please the guru, devotees are considered to be serving the guru.[48]:389 This relationship is the driving force for the spiritual actions of devotees. The guru is Mahant Swami Maharaj, who is held to be the embodiment of selfless devotion. Under the guidance of Mahant Swami Maharaj, followers observe the tenets of Swaminarayan through the above-mentioned practices, striving to please the guru and become close to God.[91]

BAPS Charities

BAPS Charities is a global non-religious, charitable organization that originated from the Bochasanwasi Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS) with a focus on serving society.[119] Their history of service activities can be traced back to Swaminarayan (1781-1830), who opened alms houses, built shelters, worked against addiction, and abolished the practice of sati and female infanticide with the goals of removing suffering and effecting positive social change.[119][120] This focus on service to society is stated in the organization's vision, that "every individual deserves the right to a peaceful, dignified, and healthy way of life. And by improving the quality of life of the individual, we are bettering families, communities, our world, and our future."[119]

BAPS Charities aims to express a spirit of selfless service through Health Awareness, Educational Services, Humanitarian Relief, Environmental Protection & Preservation and Community Empowerment. From Walkathons or Sponsored Walks that raise funds for local communities to supporting humanitarian relief in times of urgent need or from community health fairs to sustaining hospitals and schools in developing countries, BAPS Charities provides an opportunity for individuals wishing to serve locally and globally.

References

- Mamtora, Bhakti. Jacobsen, Knut A.; Basu, Helene; Malinar, Angelika; Narayanan, Vasudha (eds.). "BAPS: Pramukh Swami". Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism Online. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- Patel, Aarti (December 2018). "Secular Conflict". Nidān: International Journal for Indian Studies. 3 (2): 55–72.

- Gadhia, Smit (1 April 2016), "Akshara and Its Four Forms in Swaminarayan's Doctrine", Swaminarayan Hinduism, Oxford University Press, pp. 156–171, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199463749.003.0010, ISBN 978-0-19-946374-9

- Williams, Raymond (2001). An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65279-0.

- Rinehart, Robin (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. Library of Congress. p. 215. ISBN 1-57607-905-8.

- James, Jonathan (28 August 2017). Transnational religious movements : faith's flows. Thousand Oaks. ISBN 9789386446565. OCLC 1002848637.

- Gadhia, Smit (2016). Trivedi, Yogi; Williams, Raymond Brady (eds.). Akshara and its four forms in Swaminarayan's doctrine (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 9780199086573. OCLC 948338914.

- "BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha Today". Hinduism Today. Himalayan Academy. October–December 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Kim, Hanna (2001). Being Swarninarayan: the ontology and significance of belief in the construction of a Gujarati diaspora. Ann Arbor: Bell & Howell Information and Learning Company.

- "1,200 young adults from North America attend Spiritual Quotient Seminar". India Herald. 30 June 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Clarke, Matthew (2011). Development and Religion: Theology and Practice. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 40–49. ISBN 9781848445840.

- "BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha Today". Hinduism Today. Himalayan Academy. October–December 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Gadhada II-27 (2001). The Vachanamrut: Spiritual Discourses of Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Amdavad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. ISBN 81-7526-190-0.

- Kim, Hanna (December 2009). "Public engagement and personal desires: BAPS Swaminarayan temples and their contribution to the discourses on religion". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 13 (3): 357–390. doi:10.1007/s11407-010-9081-4.

- Williams, Raymond (2001). An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 106. ISBN 0-521-65279-0.

- Jones, Constance (2007). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8160-7336-8.

- Mukundcharandas, Sadhu. (2007). Hindu rites & rituals : sentiments, sacraments & symbols. Das, Jnaneshwar., Swaminarayan Aksharpith. (1st ed.). Amdavad, India: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. ISBN 978-8175263567. OCLC 464166168.

- "Shri Swaminarayan Mandir". Pluralism Project. Harvard University. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "BAPS celebrates Swaminarayan Jayanti & Ram Navmi". India Post. 22 April 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Kim, Hanna (2001). Being Swarninarayan: the ontology and significance of belief in the construction of a Gujarati diaspora. Ann Arbor: Bell & Howell Information and Learning Company.

- "1,200 young adults from North America attend Spiritual Quotient Seminar". India Herald. 30 June 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Dave, Hiral (20 February 2009). "Baps tells Youth to uphold values". Daily News & Analysis. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "Strive to be unique, Kalam tells youth". India Post. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Patel, Divyesh. "BAPS Commemorates Education with Educational Development Day". ChinoHills.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Padmanabhan, R. "BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha Hosts Women's Conference in Chicago". NRI Today. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Piccirilli, Amanda (13 August 2012). "BAPS Charities stresses importance of children's health". The Times Herald. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "Parents Are the Key". Hinduism Today. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "BAPS Charities". Georgetown University. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Rajda, K (29 June 2012). "Local communities join BAPS Walkathon". IndiaPost. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "BAPS Charities Hosts 15th Annual Walkathon". India West. 6 June 2012. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "BAPS Charities Host Community Walk in Support of American Diabetes Association and Stafford MSD Education Fund". Indo American News. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Gibson, Michael. "BAPS Charities Health Fair 2012". NBCUniversal. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Patel, Divyesh. "BAPS Charities to Hold Women's FREE Health Awareness Lectures 2010 on Saturday, June 5th 2010". ChinoHills.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "BAPS Care International launches relief efforts for Hurricane Katrina victims". India Herald. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "BAPS Charities helps victims of tornadoes". IndiaPost. 20 May 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "Traditional Hindu temple opening in Robbinsville, part of BAPS community". 29 July 2014.

- Kim, Hanna (2007). Gujaratis in the West: Evolving Identities in Contemporary Society, Ch. 4: Edifice Complex: Swaminarayan Bodies and Buildings in the Diaspora. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 67–70. ISBN 978-1-84718-368-2.

- "PM Modi officially launches foundation stone-laying ceremony for first Hindu temple in Abu Dhabi – Times of India ►". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- James, Jonathan D. (28 August 2017). Transnational religious movements : faith's flows. Thousand Oaks. ISBN 9789386446565. OCLC 1002848637.

- Dave, H.T (1974). Life and Philosophy of Shree Swaminarayan 1781–1830. London: George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-294082-6.

- Paranjape, edited by Makarand (2005). Dharma and development : the future of survival. New Delhi: Samvad India Foundation. p. 117. ISBN 81-901318-3-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Paranjape, edited by Makarand (2005). Dharma and development : the future of survival. New Delhi: Samvad India Foundation. p. 129. ISBN 81-901318-3-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- The Vachanamrut – Spiritual Discourses of Bhagwan Swaminarayan (An English Translation). Amdavad: Aksharpith. 2006. p. 303. ISBN 81-7526-320-2.

- Paranjape, edited by Makarand (2005). Dharma and development : the future of survival. New Delhi: Samvad India Foundation. p. 112. ISBN 81-901318-3-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Pocock, David Francis (1973). Mind, body, and wealth; a story of belief and practice in an Indian village. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 161. ISBN 0-631-15000-5. OL 17060237W.

- "The Digital Shikshapatri". Oxford's Bodleian Library. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- Williams, Raymond Brady (1984). A New Face of Hinduism. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27473-7.

- Kim, Hanna (2001). Being Swaminarayan: The Ontology and Significance of Belief in the Construction of a Gujarati Diaspora. Ann Arbor: Bell & Howell Information and Learning Company.

- The Vachanamrut – Spiritual Discourses of Bhagwan Swaminarayan (An English Translation). Amdavad: Aksharpith. 2006. ISBN 81-7526-320-2.

- Williams, Raymond Brady (2008). Encyclopedia of new religious movements Swaminarayan Hinduism Founder: Sahajanand Swami Country of origin: India (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-45383-7.

- Acharya, Viharilalji Maharaj (1911). Shri Kirtan Kaustubhmala (1st ed.). Published by Kothari Hathibhai Nanjibhai by the order of Acharya Shripatiprasadji Maharaj and Kothari Gordhanbhai. p. 13.

- Raghuvirji Maharaj, Acharya (1966). Sadhu Shwetvaikunthdas (Translator) (ed.). Shri Harililakalpataru (1st ed.). Mumbai: Sheth Maneklal Chunilal Nanavati Publishers.

- Parekh (Translator), Gujarati text, Harshadrai Tribhuvandas Dave; English translation, Amar (2011). Brahmaswarup Shri Pragji Bhakta : life and work (1st ed.). Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. p. 24. ISBN 978-81-7526-425-0.

- Ishwarcharandas, Sadhu (2009). Pragji Bhakta (Bhagatji Maharaj) - A short biography of Brahmaswarup Bhagatji Maharaj. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. p. 6. ISBN 978-81-7526-260-7.

- "Bhagatji Maharaj's Life-Realisation".

- Ishwarcharandas, Sadhu (1978). Pragji Bhakta – A short biography of Brahmaswarup Bhagatji Maharaj. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. pp. 191–192.

- Ishwarcharandas, Sadhu (2009). Pragji Bhakta (Bhagatji Maharaj) – A short biography of Brahmaswarup Bhagatji Maharaj. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. p. 38. ISBN 978-81-7526-260-7.

- Swaminarayan Bliss. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. 2008. p. 38.

- Amrutvijaydas, Sadhu (2006). Shastriji Maharaj Life and Work. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. ISBN 81-7526-305-9.

- Ishwarcharandas, Sadhu (1978). Pragji Bhakta – A short biography of Brahmaswarup Bhagatji Maharaj. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. p. 65.

- "Shashtriji Maharaj's life: No Secession from the Temple and the Satsang".

- Brahmbhatt, Arun (2014). Global Religious Movements Across Borders: Sacred Service. Oxon: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-409-45687-2.

- Amrutvijaydas, Sadhu (2007). 100 Years of BAPS. Amdavad: Aksharpith. ISBN 978-81-7526-377-2.

- Dave, Kishore M. (2009). Shastriji Maharaj - A brief biography of Brahmaswarup Shastriji Maharaj. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-81-7526-129-7.

- Dr. Preeti Tripathy (2010). Indian religions: tradition, history and culture. Axis Publications. ISBN 978-93-80376-17-2.

- Shelat, Kirit (2005). Yug Purush Pujya Pramukh Swami Maharaj – a life dedicated to others. Ahmedabad: Shri Bhagwati Trust. p. 7.

- Shelat, Kirit (2005). Yug Purush Pujya Pramukh Swami Maharaj – a life dedicated to others. Ahmedabad: Shri Bhagwati Trust. p. 8.

- Vivekjivandas, Sadhu (June 2000). "Pramukh Varni Din". Swaminarayan Bliss.

- "Pramukh Varni Din". Swaminarayan. Swaminarayan Aksharpith. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- Dave, Kishore M. (2009). Shastriji Maharaj – A brief biography of Brahmaswarup Shastriji Maharaj. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. p. 111. ISBN 978-81-7526-129-7.

- Brear, Douglas (1996). "Transmission of sacred scripture in the British East Midlands: the Vachanamritam". In Raymond Brady Williams (ed.). A sacred thread : modern transmission of Hindu traditions in India and abroad (Columbia University Press ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10779-X.

- "Yogiji Maharaj – Sermons of Yogiji Maharaj". Swaminarayan. Swaminarayan Aksharpith. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- Younger, Paul (2010). New homelands : Hindu communities in Mauritius, Guyana, Trinidad, South Africa, Fiji, and East Africa ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-19-539164-0.

- Salvadori, Cynthia (1989). "Revivals, reformations & revisions of Hinduism; the Swaminarayan religion". Through Open Doors : A View of Asian Cultures in Kenya: 127.

- Salvadori, Cynthia (1989). "Revivals, reformations & revisions of Hinduism; the Swaminarayan religion". Through Open Doors : A View of Asian Cultures in Kenya: 128.

- Shelat, Kirit (2005). Yug Purush Pujya Pramukh Swami Maharaj – a life dedicated to others. Ahmedabad: Shri Bhagwati Trust. p. 17.

- Heath, edited by Deana; Mathur, Chandana (2010). Communalism and globalization in South Asia and its diaspora. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-203-83705-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kurien, Prema A. (2007). A place at the multicultural table : the development of an American Hinduism ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). New Brunswick, NJ [u.a.]: Rutgers Univ. Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-8135-4056-6.

- Jones, Constance A.; Ryan, James D. (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. New York: Checkmark Books. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-8160-7336-8.

- Kurien, Prema A. (2007). A place at the multicultural table : the development of an American Hinduism (online ed.). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-8135-4056-6.

- Kim, Hanna Hea-Sun (2001). "Being Swaminarayan – The Ontology and Significance of Belief in the Construction of a Gujarati Diaspora". Dissertation Abstracts International, Section A: The Humanities and Social Sciences. 62 (2): 77. ISSN 0419-4209.

- Jones, Lindsay (2005). Encyclopedia of religion. Detroit : Macmillan Reference USA/Thomson Gale, c2005. p. 8891. ISBN 978-0028659824.

- "Bhagwan Swaminarayan's Spiritual Lineage". BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- Sadhu, Amrutvijaydas (December 2007). 100 Years of BAPS. Amdavad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. p. 169. ISBN 978-8175263772.

- Staff, India West. "BAPS Inaugurates Stone Mandir in New Jersey". India West. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Pramukh Swami's Vicharan". BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- Kim, Hanna Hea-Sun (2012). "A Fine Balance: Adaptation and Accommodation in the Swaminarayan Sanstha". Gujarati Communities Across the Globe: Memory, Identity and Continuity. Edited by Sharmina Mawani and Anjoom Mukadam. Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom: Trentham Books: 141–156. doi:10.1111/rsr.12043_9.

- "Pramukh Swami's Work". BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- Angela, Rudert (11 May 2004). "Inherent Faith and Negotiated Power: Swaminarayan Women in the United States". hdl:1813/106. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "700 BAPS Sadhus". BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- "Final Darshan and Rites of Pramukh Swami Maharaj". BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- Kulkarni, Deepali (December 2018). "Digital Mūrtis, Virtual Darśan and a Hindu Religioscape". Nidān: International Journal for Indian Studies. 3 (2): 40–54.

- Mangalnidhidas, Sadhu (2019). Sacred Architecture and Experience BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, Robbinsville, New Jersey. Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. p. 100. ISBN 978-19-4746-101-7.

- Writer, Staff. "BAPS Temple holds installation of 1st pillar, Mandapam, and Visarjan in New Jersey | News India Times". Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- "Everything we know about the UAE's first traditional Hindu temple". The National. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- "Guruhari Ashirwad - YouTube". YouTube. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Gadhada I-21 The Vachanamrut: Spiritual Discourses of Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. 2003. 2nd edition. ISBN 81-7526-190-0, pg. 31.

- Paramtattvadas, Swami (2017). An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hindu Theology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316611272.

- Williams, Raymond Brady (2004). "The Holy Man as the Abode of God in Swaminarayan Hinduism". Williams on South Asian Religions and Immigration; Collected Works (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.)

- Amrutvijaydas, Sadhu; Williams, Raymond Brady; Paramtattvadas, Sadhu (1 April 2016). Swaminarayan and British Contacts in Gujarat in the 1820s. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199463749.003.0005. ISBN 9780199086573.

- Bhadreshdas, Sadhu (April–June 2014). "Guru's grace empowers philosophical treatise". Hinduism Today.

- Mukundcharandas, Sadhu (2004). Vachnamrut Handbook (Insights into Bhagwan Swaminarayan's Teachings). Amdavad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. p. 154. ISBN 81-7526-263-X

- Vachnamrut, Gadhada I-46, The Vachanamrut: Spiritual Discourses of Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. 2003. 2nd edition. ISBN 81-7526-190-0 p. 87.

- Mukundcharandas, Sadhu (2004). Vachnamrut Handbook (Insights into Bhagwan Swaminarayan's Teachings). Amdavad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. ISBN 81-7526-263-X p. 158

- The Vachanamrut: Spiritual Discourses of Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. 2003. 2nd edition. p. 729. ISBN 81-7526-190-0

- Mukundcharandas, Sadhu (2004). Vachnamrut Handbook (Insights into Bhagwan Swaminarayan's Teachings). Amdavad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. ISBN 81-7526-263-X p. 157

- Mukundcharandas, Sadhu (2004). Vachnamrut Handbook (Insights into Bhagwan Swaminarayan's Teachings). Amdavad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. ISBN 81-7526-263-X p. 155-156

- Amrutvijaydas, Sadhu (2006). Shastriji Maharaj Life and Work. Amdavad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith.ISBN 81-7526-305-9.

- Acharya, Raghuvirji Maharaj; Sadhu Shwetvaikunthdas (Translator) (1966). Shri Harililakalpataru (1st ed.). Mumbai: Sheth Maneklal Chunilal Nanavati Publishers.

- Dave, Kishorebhai (2012). Akshar Purushottam Upasana As Revealed by Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. p. 138. ISBN 978-81-7526-432-8.

- Vachanamrut, Gadhada I-37, The Vachanamrut: Spiritual Discourses of Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. 2003. 2nd edition. ISBN 81-7526-190-0, p. 65

- Vartal 5. The Vachanamrut: Spiritual Discourses of Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. 2003. 2nd edition. p. 536–537. ISBN 81-7526-190-0

- Vachanamrut, Vartal 5, The Vachanamrut: Spiritual Discourses of Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. 2003. 2nd edition, p.534

- G. Sundaram. The Concept of Social Service in the Philosophy of Sri Swaminarayan. p. 45

- Mukundcharandas, Sadhu (2004). Vachnamrut Handbook (Insights into Bhagwan Swaminarayan's Teachings). Amdavad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. ISBN 81-7526-263-X p. 160

- G. Sundaram. The Concept of Social Service in the Philosophy of Sri Swaminarayan. p. 43

- Shikshapatri, shloka 116.

- "FAQ-Related to BAPS Swaminaryan Sansthã-General".

- Clarke, Matthew (2011). Development and Religion: Theology and Practice. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 40–49. ISBN 978-1-84844-584-0.

- Paranjape, Makarand (2005). Dharma and Development: The Future of Survival. New Delhi: Samvad India Foundation. p. 119. ISBN 81-901318-3-4.