Aggravated felony

The term aggravated felony was created by the United States Congress as part of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) to define a special category of criminal offenses.[1][2] The INA says that certain aliens "convicted of an aggravated felony shall be considered to have been convicted of a particularly serious crime."[3] Every "legal immigrant," including a "national but not a citizen of the United States,"[4] who has been convicted of any aggravated felony is ineligible for citizenship of the United States,[5][6][7][8] and other than a refugee,[9][10][11][12] every alien who has been convicted of any aggravated felony is ineligible to receive a visa or be admitted to the United States, if his or her "term of imprisonment was completed within the previous 15 years."[2][13][14][15][16][17]

When the aggravated felony was introduced in 1988, it encompassed only murder and felony trafficking in drugs and/or firearms (but not long shotguns, long rifles, and/or ammunition of such legal weapons).[1][18] Every aggravated felony conviction was manifestly a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year.[1][19] The 1996 enactment of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) tremendously expanded the aggravated felony definition by adding a great many more criminal convictions.[20] All the aggravated felonies are enumerated in the chart at the very bottom.

Background

The INA states that "[t]he term 'alien' means any person not a citizen or national of the United States."[22] The terms "inadmissible aliens" and "deportable aliens" are synonymous,[23] which mainly refer to the INA violators among the 75 million or so foreign nationals who are admitted each year as guests,[24][25] the 12 million or so illegal aliens,[26] and the INA violators among the 300,000 or more foreign nationals who possess the temporary protected status (TPS).[27][28][29]

A legal immigrant, particularly one who was admitted as a refugee pursuant to 8 U.S.C. § 1157(c), can either be a national of the United States (American) or an alien, which requires a case-by-case analysis and depends mainly on the number of continuous years he or she has physically spent in the United States as a lawful permanent resident (LPR).[30][10][31][32][33][34][35]

Firm resettlement of refugees in the United States

U.S. Presidents and the U.S. Congress have expressly favored some "legal immigrants"[36] because the U.S. Attorney General had admitted them to the United States as refugees, i.e., people who experienced genocides in the past and have no safe country of permanent residence other than the United States.[9][11][12][33][10][37] Removing such protected people from the United States constitutes a grave international crime,[38][39][40][41][42][36] especially if they qualify as Americans or have physically and continuously resided in the United States for at least 10 years without committing (in such years) any offense that triggers removability.[11][12][10][32][34][35]

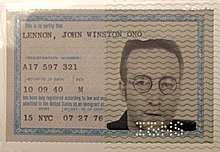

In 1982, the U.S. Supreme Court reminded all immigration officials that "once an alien gains admission to our country and begins to develop the ties that go with permanent residence, his constitutional status changes accordingly."[43] That opinion was issued after Congress and the Reagan administration firmly resettled in the United States thousands of refugee families from totalitarian states, such as Afghanistan, Cambodia, Cuba, Laos, Vietnam, etc.[9][44][45][46][47] As U.N.-recognized refugees, these people had permanently lost their homes, farms, businesses, properties, livelihood, families, relatives, pets, etc. They similarly lost their former nationalities after obtaining permanent resident cards (green cards) of the United States, and thus gradually became like the rest of Americans.[48][4]

Expansion of the definition of "nationals but not citizens of the United States"

In 1986, less than a year before the United Nations Convention against Torture (CAT) became effective, Congress expressly and intentionally expanded the definition of "nationals but not citizens of the United States" by adding paragraph (4) to 8 U.S.C. § 1408, which states that:

the following shall be nationals, but not citizens, of the United States at birth: .... (4) A person born outside the United States and its outlying possessions of parents one of whom is an alien, and the other a national, but not a citizen, of the United States who, prior to the birth of such person, was physically present in the United States or its outlying possessions for a period or periods totaling not less than seven years in any continuous period of ten years—(A) during which the national parent was not outside the United States or its outlying possessions for a continuous period of more than one year, and (B) at least five years of which were after attaining the age of fourteen years.[4][49]

The natural reading of § 1408(4) demonstrates that it was not exclusively written for the 55,000 American Samoans but for all people who statutorily and manifestly qualify as "nationals but not citizens of the United States."[4][50][16] This means that any person who can show by a preponderance of the evidence that he or she meets (or at any time has met) the requirements of 8 U.S.C. §§ 1408(4), 1427, 1429, 1436, and/or 1452, is plainly and unambiguously an American.[31][32][10][34][35] Such person must never be labelled or treated as an alien. "Deprivation of [nationality]—particularly American [nationality], which is one of the most valuable rights in the world today—has grave practical consequences."[51][38][39][40][41][42][36][52][53] This legal finding "is consistent with one of the most basic interpretive canons, that a statute should be construed so that effect is given to all its provisions, so that no part will be inoperative or superfluous, void or insignificant."[15] Under the well known Chevron doctrine, "[i]f the intent of Congress is clear, that is the end of the matter, for the court as well as the [Attorney General] must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress."[54]

Introduction and amendment of the term "aggravated felony"

In 1988, Congress introduced the term "aggravated felony" by defining it under 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a),[1] which was amended several times over the years. As of September 30, 1996, an "aggravated felony" only applies to convictions "for which the term of imprisonment was completed within the previous 15 years."[2][13][15][16][17] After the successful elapse of said "15 years" (i.e., without sustaining another aggravated felony conviction), a longtime LPR automatically becomes entitled to both cancellation of removal and a waiver of inadmissibility.[10] He or she may (at any time and from anywhere in the world[55][56][57][58]) request these popular immigration benefits depending on whichever is more applicable or easiest to obtain.[59][2][60]

The phrase "term of imprisonment" in the INA expressly excludes all probationary periods.[19] Only a court-imposed suspended sentence (i.e., suspended term of imprisonment) is included,[61] which must be added to the above 15 years, and it makes no difference if the aggravated felony conviction was sustained in Afghanistan, American Samoa, Australia, Canada, Mexico, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, the United States, or in any other country or place in the world.[2][13][62][15][16][17]

Consequences of an aggravated felony conviction

In February 1995, while IIRIRA was being prepared, U.S. President Bill Clinton issued an important directive in which he expressly stated the following:

Our efforts to combat illegal immigration must not violate the privacy and civil rights of legal immigrants and U.S. citizens. Therefore, I direct the Attorney General, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and other relevant Administration officials to vigorously protect our citizens and legal immigrants from immigration-related instances of discrimination and harassment. All illegal immigration enforcement measures shall be taken with due regard for the basic human rights of individuals and in accordance with our obligations under applicable international agreements. (emphasis added).[36][49]

Despite what President Clinton said in the above directive, some plainly incompetent immigration officers began deporting longtime LPRs (i.e., potential Americans).[10][9][21][4] Many of these legal immigrants were firmly resettled and non-deportable refugees,[11][12][48] who statutorily qualified as Americans after continuously residing in the United States for at least 10 years without committing (in such years) any offense that triggers removability.[30][4][59] This appears to be the reason why the permanent resident card (green card) is valid for 10 years. It was expected that all refugees in the United States would equally obtain U.S. citizenship within 10 years from the date of their lawful entry,[63][64] but if that was unachievable then they would statutorily become "nationals but not citizens of the United States" after the successful elapsing of such continuous 10 years.[16] This specific class of people owe permanent allegiance solely to the United States,[22] and that obviously makes them nothing but Americans.[21][59] Anything to the contrary leads to "deprivation of rights under color of law," which is a federal crime.[38][39][40][41][42][51][36]

An aggravated felony conviction affects both aliens and "nationals but not citizens of the United States."[4][5][7][8][6] However, unlike a "national but not a citizen of the United States," an alien convicted of any aggravated felony statutorily becomes "removable" from the United States,[23] but only if his or her "term of imprisonment was completed within the previous 15 years."[2][13][15][16][17] In other words, such alien cannot:

- have his or her removal proceedings terminated without a written legal order issued by any immigration judge or member of the BIA,[65] or an injunction issued by any federal judge.[66][31][67]

- be admitted to the United States prior to being granted a waiver of inadmissibility or cancellation of removal by any authorized U.S. immigration official,[59][11][12] or "a full and unconditional pardon by the President of the United States or by the Governor of any of the several States."[68]

- obtain asylum in the United States unless he or she was previously admitted to the United States as a refugee,[11][12] or his or her aggravated felony was shown not to be a particularly serious crime.[3] An alien convicted of a particularly serious crime may still receive asylum, so long as he or she is not "a danger to the community of the United States,"[69] or at minimum deferral of removal under the CAT.[70] It must be added that granting the CAT is not discretionary but statutory and mandatory.[71][3]

- obtain adjustment of status unless he or she was previously admitted to the United States as a refugee.[11][12]

- obtain voluntary departure.[72]

Challenging an aggravated felony charge

An "order of deportation" may be reviewed at any time by any immigration judge or any BIA member and finally by any authorized federal judge.[56] Particular cases, especially those that were adjudicated in any U.S. district court prior to the enactment of the Real ID Act of 2005, can be reopened under Rule 60 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.[58] The review of the order does not require the alien (or the American) to remain in the United States. It can be requested from anywhere in the world via mail (e.g., Canada Post, DHL, FedEx, UPS, etc.) and/or electronic court filing (ECF),[55] and the case can be filed in any court the alien (or the American) finds appropriate.[10] In other words, if one court refuses help, he or she may proceed to another.[10]

Every United States nationality claim, illegal deportation claim, CAT or asylum claim, etc., is adjudicated under 8 U.S.C. §§ 1252(a)(4), 1252(b)(4), 1252(b)(5), 1252(d), 1252(e)(4)(B) and 1252(f)(2). When these specific provisions are invoked, all other contrary provisions of law, especially § 1252(b)(1) and any related case law, must be disregarded because these three claims manifestly constitute exceptional circumstances.[58][31][32][66][67] In removal proceedings, the focus is solely on whether or not the person belongs in the United States (as a matter of law). If he or she does then dismissing the case for lack of jurisdiction or delaying relief is plainly detrimental to the United States.[39][38][41][42][52][53][36][51] The Supreme Court has pointed out in 2009 that "the context surrounding IIRIRA's enactment suggests that § 1252(f)(2) was an important—not a superfluous—statutory provision."[73] In this regard, Congress has long warned every public official by expressly stating the following:

Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or to different punishments, pains, or penalties, on account of such person being an alien, or by reason of his color, or race, than are prescribed for the punishment of citizens, shall be subject to specified criminal penalties.[74][38][39][40][41][42][36]

According to § 1252(f)(1), "no court (other than the Supreme Court)" is authorized to determine which two or more people in removal proceedings should be recognized as nationals of the United States (Americans).[66] This includes parents and children or relatives.[4][31] The remaining courts, however, are fully empowered by §§ 1252(b)(5), 1252(e) and 1252(f)(2) to, inter alia, issue an injunction to cancel or terminate any person's removal proceedings; return any previously removed person to the United States; and/or to confer United States nationality upon any person (but only using a case-by-case analysis).[66][67][31] In addition to that, under 8 C.F.R. 239.2, any immigration official mentioned in 8 C.F.R. 239.1 may at any time move to: (1) terminate the removal proceedings of any person who turns out to be an American; or (2) cancel the removal proceedings of anyone who is clearly not "removable" under the INA.[23][65] The burden of proof is on the alien (or the American) to establish a prima facie entitlement to re-admission after the deportation has been completed.[57][56]

Legal conflict between an aggravated felony and a misdemeanor

Under the INA, the term "sentence" explicitly refers to any form of punishment that must be served inside a prison.[61] Any "street time" (i.e., period of probation, parole, or supervised release) that was imposed as part of the defendant's sentence plainly does not count as term of imprisonment.[61][75][76] A sentence of imprisonment with parole is called a "bifurcated sentence,"[77] and various U.S. courts of appeals have held that this is not a suspended sentence.[78][49] House arrest is also not imprisonment for INA purposes.[76]

Courts have held that a misdemeanor conviction qualifies as an aggravated felony if the trial court or sentencing court orders at least one year of imprisonment.[19] In this regard, Judge Becker of the Third Circuit had explained in 1999 the following:

The line between felonies and misdemeanors is an ancient one. The line has not always been drawn between one year and one year and a day, since it used to be that felonies were all punishable by death.... Furthermore, under federal law, a felony is defined as a crime that has a maximum term of more than one year.... Because, as the government contends, the amended statute's definition of an aggravated theft felony refers to sentences actually imposed and not to potential sentences, it is still possible for a [defendant] to avoid being an aggravated felon if he or she receives a six-month sentence for a theft crime with a maximum possible sentence over one year....[79]

It is important to note that a court cannot defy a clearly-established law.[15] Under the INA, a crime must be punishable by imprisonment for a term "exceeding" one year in order to be considered a conviction of a "crime involving moral turpitude" (CIMT) or an aggravated felony.[19][80][1][81] Anything to the contrary will lead to an absurd result and a blatant violation of the U.S. Constitution.[38][39][41][42] Plus, it will damage the reputation of the appellate court,[82] which suppose to play a more neutral role in removal proceedings under the INA because they are obviously not criminal proceedings.[83][56] Congress has long stated in that "[t]he term [aggravated felony] does not include ... any State offense classified by the laws of the State as a misdemeanor and punishable by a term of imprisonment of two years or less." This expressed language of Congress was in effect in 1988 (when the aggravated felony was coined for the first time) and is still in effect today.[1][19]

Section 921(a)(20) applies to the entire Chapter 44 (§§ 921-931) of title 18. As such, § 921(a)(20) controls 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(43), especially subparagraphs (A), (B), (C), (D), (E), (F) and (G).[84] Under § 921(a)(20), Congress says this: "What constitutes a conviction of such a crime shall be determined in accordance with the law of the jurisdiction in which the proceedings were held." This simply means that the federal felony definition controls in all immigration-related cases.[85] More importantly, in § 927 ("Effect on State law"), Congress expressly states: "No provision of this chapter shall be construed as indicating an intent on the part of the Congress to occupy the field in which such provision operates to the exclusion of the law of any State on the same subject matter...." The phrase "[n]o provision of this chapter" statutorily covers (among many other crimes) every crime of violence and theft.[84] See also the below section: Comparison of an aggravated felony to a crime involving moral turpitude.

Precedents relating to "crime of violence" under U.S. law

In 2001, the Fifth Circuit held "that because intentional force against the person or property of another is seldom, if ever, employed to commit the offense of felony DWI, such offense is not a crime of violence within the meaning of 18 U.S.C. § 16(b)."[86] Later in the same year, the Third Circuit held that unintentional vehicular homicide is not an aggravated felony.[87] In Leocal v. Ashcroft (2004), the U.S. Supreme Court held that driving under the influence is not an aggravated felony if the DUI statute that defines the offense does not contain a mens rea element or otherwise allows a conviction for merely negligent conduct. In 2005, the Third Circuit held that a misdemeanor "simple assault" does not constitute an aggravated felony.[88] "And the Supreme Court recently declared, in Sessions v. Dimaya... (2018), that § 16(b) is unconstitutionally vague and, therefore, cannot be the basis for an aggravated felony."[89]

Comparison of an aggravated felony to a crime involving moral turpitude

The term "crime involving moral turpitude" (CIMT) refers to a specific conviction in which a court of law has imposed upon an alien a "term of imprisonment in excess of 6 months (regardless of the extent to which the sentence was ultimately executed)."[80][19] Congress made a clear distinction between LPRs and "nonpermanent residents" in this regard.[90][83] In the case of an LPR, the CIMT must be committed within 5 years of his or her admission to the United States.[90] However, despite the obvious differences, both classes of aliens are statutorily entitled to a waiver of inadmissibility and cancellation of removal, so long as "the maximum penalty possible for the crime of which the alien[s] w[ere] convicted ... did not exceed imprisonment for one year...." (emphasis added).[80][19] Any period of incarceration or confinement that was subsequently added due to probation/parole violation plainly does not count.[75][78] If the total period served inside a penal institution was less than 180 days (i.e., 6 months),[76] the LPR is manifestly entitled to U.S. citizenship, provided that the remaining citizenship requirements are fulfilled.[31] Such person may be naturalized at any time,[91] whether in the United States or (in particular cases) at any U.S. embassy around the world.[92][31][32][66][73]

The consequences of making a crime an "aggravated felony" are far reaching. One major consequence is that, unlike the deportation ground for a CIMT, an aggravated felony does not necessarily have to be committed within five years from the alien's entry or admission into the United States to make him or her removable.[23] An alien who cannot demonstrate U.S. nationality is removable even if the alien has committed an aggravated felony in a foreign country, either before or after entering the United States.[93] In this regard, the INA expressly states the following:

The term [aggravated felony] applies to an offense described in this paragraph whether in violation of Federal or State law and applies to such an offense in violation of the law of a foreign country for which the term of imprisonment was completed within the previous 15 years. Notwithstanding any other provision of law (including any effective date), the term [aggravated felony] applies regardless of whether the conviction was entered before, on, or after September 30, 1996. (emphasis added).[2][94][15][16]

8 U.S.C. §§ 1101(a)(43) and "1252(f)(2) should be interpreted to avoid absurd results."[95] Section 1227(a)(2)(A)(iii) states that every "alien who is convicted of an aggravated felony at any time after admission is deportable." (emphasis added). It is obviously an absurd result to presume that the "15 years" in the above quoted provision applies only to those who were convicted of an aggravated felony in countries outside the United States. The plain language and skillful structure of the above quoted provision defeats that presumption because all the crimes enumerated in § 1101(a)(43) are obviously in violation of the law of every country on earth. There are countless other cogent reasons why Congress never intended such a bizarre and unconstitutional result. It would basically mean that Congress is somehow advising admitted aliens to, inter alia, murder or rape a person in Mexico instead of the United States. It would ridiculously ban all LPRs but allow only illegal aliens convicted of aggravated felonies outside the United States to receive immigration benefits.[15] The only logical explanation is that the above 15-year period equally rehabilitates all non-citizens against committing another aggravated felony.[96][36]

Notwithstanding any other provision of law

"The ordinary meaning of 'notwithstanding' is 'in spite of,' or 'without prevention or obstruction from or by.'"[97] Congress is clearly and unambiguously saying that the penultimate provision under § 1101(a)(43), as quoted above, controls over the text of §§ 1101(f)(8), 1158(b)(2)(B)(i), 1225, 1226(c)(1)(B), 1227(a)(2)(A)(iii), 1228, 1229b(a), 1231, 1252(a)(2)(C), etc.[94] "In statutes, the [notwithstanding any other provision of law] 'shows which provision prevails in the event of a clash.'"[97] Courts have long explained that "the phrase 'notwithstanding any other provision of law' expresses the legislative intent to override all contrary statutory and decisional law."[17]

What this means is that holdings such as Stone v. INS, 514 U.S. 386, 405 (1995) (case obviously decided prior to IIRIRA of 1996, which materially changed the old "judicial review provisions of the INA"),[20] are statutorily not binding upon any agency or any court.[98][58] Congress clearly spoken about this at 8 U.S.C. § 1252(d)(2) (eff. April 1, 1997). Its intent was sufficiently shown when amending § 1252 during the enactment of the Real ID Act of 2005. There, it added "(statutory or nonstatutory)" after every relevant "notwithstanding any other provision of law" in § 1252.[99] The overall purpose of this is obviously to protect the United States[100][101][102] and the over 13 million[30] LPRs against lawless government actions.[38][39][40][103][104] In other words, the lives of these vulnerable people should not be in the hands of a few judges,[105][106] who often make serious reversible errors in immigration-related cases.[107] An unknown number of these LPRs statutorily qualify as Americans.[31][4][32]

The job of Congress is to equally punish or protect everyone in the United States,[108][103][104][109][110] not only those who merely possess a simple paper showing U.S. citizenship. In many cases, such documents are forged and/or criminally obtained.[111][112][113][7][114][115] Congress instructed the courts by using plain language in § 1252(f)(2) ("Particular cases") to apply plenary power and de novo review.[66][73] Even a high school student can understand that this particular INA provision automatically redresses any deportation case, without the need to look at other provisions of law.[17]

Consequences of illegal re-entry after deportation

Every non-immigrant convicted of any aggravated felony and lawfully removed "must remain outside of the United States for twenty consecutive years from the deportation date before he or she is eligible to re-enter the United States."[116] That stringent rule, however, does not apply to legal immigrants (i.e., refugees and LPRs) who have been deported as aggravated felons.[48][60][2][11][12][98][15][16][17] Many previously removed people are believed to be residing inside the United States, some of whom have been removed from the United States about a dozen of times.[117][118]

According to the INA, it is a federal crime for any non-criminal alien to illegally enter the United States after that alien has been denied entry, excluded, removed, deported, or if he or she has departed the United States while an order of removal was outstanding. The maximum sentence for this crime is 2 years of imprisonment. However, if he or she was a criminal alien and "whose removal was subsequent to a conviction for commission of three or more misdemeanors involving drugs, crimes against the person, or both, or a felony (other than an aggravated felony), such alien shall be fined under title 18, imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both."[119]

The penalty can be increased to as high as 20 years of imprisonment in the case of an alien who was convicted of a particularly serious crime or an aggravated felony and then illegally reentered the United States. Such penalty, however, is extremely rare since no alien has received that many years of imprisonment. Most defendants in such cases receive around 5 years of imprisonment. The only person saved from guilt and serving any imprisonment for illegal reentry after deportation is someone who "was not originally removable as charged, and so could not be convicted of illegal reentry."[120][60]

List of aggravated felonies

| Letter Grade | 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(43) |

|---|---|

| (A) | murder, rape, or sexual abuse of a minor; |

| (B) | illicit trafficking in a controlled substance (as defined in section 802 of title 21), including a drug trafficking crime (as defined in section 924(c) of title 18); |

| (C) | illicit trafficking in firearms or destructive devices (as defined in section 921 of title 18) or in explosive materials (as defined in section 841(c) of that title); |

| (D) | an offense described in section 1956 of title 18 (relating to laundering of monetary instruments) or section 1957 of that title (relating to engaging in monetary transactions in property derived from specific unlawful activity) if the amount of the funds exceeded $10,000; |

| (E) | an offense described in — (i) section 842(h) or (i) of title 18, or section 844(d), (e), (f), (g), (h), or (i) of that title (relating to explosive materials offenses); (ii) section 922(g)(1), (2), (3), (4), or (5), (j), (n), (o), (p), or (r) or 924(b) or (h) of title 18 (relating to firearms offenses); or (iii) section 5861 of title 26 (relating to firearms offenses); |

| (F) | a crime of violence (as defined in section 16 of title 18, but not including a purely political offense) for which the term of imprisonment is at least one year; |

| (G) | a theft offense (including receipt of stolen property) or burglary offense for which the term of imprisonment is at least one year; |

| (H) | an offense described in section 875, 876, 877, or 1202 of title 18 (relating to the demand for or receipt of ransom); |

| (I) | an offense described in section 2251, 2251A, or 2252 of title 18 (relating to child pornography); |

| (J) | an offense described in section 1962 of title 18 (relating to racketeer influenced corrupt organizations), or an offense described in section 1084 (if it is a second or subsequent offense) or 1955 of that title (relating to gambling offenses), for which a sentence of one year imprisonment or more may be imposed; |

| (K) | an offense that — (i) relates to the owning, controlling, managing, or supervising of a prostitution business; (ii) is described in section 2421, 2422, or 2423 of title 18 (relating to transportation for the purpose of prostitution) if committed for commercial advantage; or (iii) is described in any of sections 1581–1585 or 1588–1591 of title 18 (relating to peonage, slavery, involuntary servitude, and trafficking in persons); |

| (L) | an offense described in — (i) section 793 (relating to gathering or transmitting national defense information), 798 (relating to disclosure of classified information), 2153 (relating to sabotage) or 2381 or 2382 (relating to treason) of title 18; (ii) section 421 of title 50 (relating to protecting the identity of undercover intelligence agents); or (iii)section 421 of title 50 (relating to protecting the identity of undercover agents); |

| (M) | an offense that — (i) involves fraud or deceit in which the loss to the victim or victims exceeds $10,000; or (ii) is described in section 7201 of title 26 (relating to tax evasion) in which the revenue loss to the Government exceeds $10,000; |

| (N) | an offense described in paragraph (1)(A) or (2) of section 1324(a) of this title (relating to alien smuggling), except in the case of a first offense for which the alien has affirmatively shown that the alien committed the offense for the purpose of assisting, abetting, or aiding only the alien’s spouse, child, or parent (and no other individual) to violate a provision of this chapter; |

| (O) | an offense described in section 1325(a) or 1326 of this title committed by an alien who was previously deported on the basis of a conviction for an offense described in another subparagraph of this paragraph; |

| (P) | an offense (i) which either is falsely making, forging, counterfeiting, mutilating, or altering a passport or instrument in violation of section 1543 of title 18 or is described in section 1546(a) of such title (relating to document fraud) and (ii) for which the term of imprisonment is at least 12 months, except in the case of a first offense for which the alien has affirmatively shown that the alien committed the offense for the purpose of assisting, abetting, or aiding only the alien’s spouse, child, or parent (and no other individual) to violate a provision of this chapter; |

| (Q) | an offense relating to a failure to appear by a defendant for service of sentence if the underlying offense is punishable by imprisonment for a term of 5 years or more; |

| (R) | an offense relating to commercial bribery, counterfeiting, forgery, or trafficking in vehicles the identification numbers of which have been altered for which the term of imprisonment is at least one year; |

| (S) | an offense relating to obstruction of justice, perjury or subornation of perjury, or bribery of a witness, for which the term of imprisonment is at least one year; |

| (T) | an offense relating to a failure to appear before a court pursuant to a court order to answer to or dispose of a charge of a felony for which a sentence of 2 years’ imprisonment or more may be imposed; and |

| (U) | an attempt or conspiracy to commit an offense described in this paragraph. |

References

This article in most part is based on law of the United States, including statutory and latest published case law.

- "Subtitle J—Provisions Relating to the Deportation of Aliens Who Commit Aggravated Felonies, Pub. L. 100-690, 102 Stat. 4469-79, § 7342". U.S. Congress. November 18, 1988. pp. 289–90. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

Section 101(a) (8 U.S.C. 1101(a)) is amended by adding at the end thereof the following new paragraph: '(43) The term 'aggravated felony' means murder, any drug trafficking crime as defined in section 924(c)(2) of title 18, United States Code, or any illicit trafficking in any firearms or destructive devices as defined in section 921 of such title....' (emphasis added).

- (emphasis added); Matter of Vasquez-Muniz, 23 I&N Dec. 207, 211 (BIA 2002) (en banc) ("This penultimate sentence, governing the enumeration of crimes in section 101(a)(43) of the Act, refers the reader to all of the crimes 'described in' the aggravated felony provision."); Luna Torres v. Lynch, 578 U.S. ___, ___, 136 S.Ct. 1623, 1627 (2016) ("The whole point of § 1101(a)(43)'s penultimate sentence is to make clear that a listed offense should lead to swift removal, no matter whether it violates federal, state, or foreign law."); see also 8 C.F.R. 1001.1(t) ("The term aggravated felony means a crime ... described in section 101(a)(43) of the Act. This definition is applicable to any proceeding, application, custody determination, or adjudication pending on or after September 30, 1996, but shall apply under section 276(b) of the Act only to violations of section 276(a) of the Act occurring on or after that date.") (emphasis added).

- ; Gomez-Sanchez v. Sessions, 892 F.3d 985, 990 (9th Cir. 2018) ("The grant of withholding of removal is mandatory if an individual proves that his 'life or freedom would be threatened in [the] country [to which he or she would be removed] because of [his or her] race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.'") (quoting INA § 241(b)(3)(A), ).

- 8 U.S.C. § 1408 (emphasis added); see also 8 U.S.C. § 1436 ("Nationals but not citizens...."); 8 U.S.C. § 1452 ("Certificates of citizenship or U.S. non-citizen national status; procedure"); 22 C.F.R. 51.1 ("U.S. non-citizen national means a person on whom U.S. nationality, but not U.S. citizenship, has been conferred at birth under 8 U.S.C. 1408, or under other law or treaty, and who has not subsequently lost such non-citizen nationality.") (emphasis added); "Certificates of Non Citizen Nationality". Bureau of Consular Affairs. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

If a person believes he or she is eligible under the law as a non-citizen national of the United States and the person complies with the provisions of section 341(b) of the INA, 8 USC 1452(b),he/she may apply for a passport at any Passport Agency in the United States.. When applying, applicants must execute a Form DS-11 and show documentary proof of their non-citizen national status as well as their identity.

- See generally, ; ; .

- Al-Sharif v. United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, 734 F.3d 207 (3d Cir. 2013) (en banc) (denying U.S. citizenship to an aggravated felon); see also Mobin v. Taylor, 598 F.Supp.2d 777 (E.D. Va. 2009) (same).

- "Justice Department Seeks to Revoke Citizenship of Convicted Felons Who Conspired to Defraud U.S. Export-Import Bank of More Than $24 Million". Office of Public Affairs. U.S. Dept. of Justice (DOJ). May 8, 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- "Justice Department Secures Denaturalization of Guardian Convicted of Sexual Abuse of A Minor". Office of Public Affairs. U.S. Dept. of Justice (DOJ). August 13, 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- ("The term 'refugee' means ... any person who is outside any country of such person's nationality or, in the case of a person having no nationality, is outside any country in which such person last habitually resided, and who is unable ... to return to, and is unable ... to avail himself ... of the protection of, that country because of persecution ... on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion....") (emphasis added); Mashiri v. Ashcroft, 383 F.3d 1112, 1120 (9th Cir. 2004) ("Persecution may be emotional or psychological, as well as physical.").

- Ahmadi v. Ashcroft, et al., No. 03-249 (E.D. Pa. Feb. 19, 2003) ("Petitioner in this habeas corpus proceeding, entered the United States on September 30, 1982 as a refugee from his native Afghanistan. Two years later, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (the 'INS') adjusted Petitioner's status to that of a lawful permanent resident.... The INS timely appealed the Immigration Judge's decision to the Board of Immigration Appeals (the 'BIA').") (Baylson, District Judge); Ahmadi v. Att'y Gen., 659 F. App'x 72 (3d Cir. 2016) (slip opinion, pp.2, 4 & n.1) (invoking statutorily nullified case law, the court dismissed an obvious illegal deportation case by asserting that it lacks jurisdiction to review an unopposed United States nationality claim under and solely due to ) (non-precedential); Ahmadi v. Sessions, No. 16-73974 (9th Cir. Apr. 25, 2017) (same; unpublished single-paragraph order); Ahmadi v. Sessions, No. 17-2672 (2d Cir. Feb. 22, 2018) (same; unpublished single-paragraph order); cf. Hamer v. Neighborhood Housing Servs. of Chicago, 583 U.S. ___, ___, 138 S.Ct. 13, 17-18 (2017) ("Mandatory claim-processing rules ... may be waived or forfeited."); United States v. Wong, 575 U.S. ___, ___, 135 S.Ct. 1625, 1632 (2015) ("In recent years, we have repeatedly held that procedural rules, including time bars, cabin a court's power only if Congress has 'clearly stated' as much.") (brackets omitted); Eberhart v. United States, 546 U.S. 12, 19 (2005) ("These claim-processing rules [provide] [injunctive] relief to a party properly raising them, but do not compel the same result if the party forfeits them."); Missouri v. Jenkins, 495 U.S. 33, 45 (1990) ("We have no authority to extend the period for filing except as Congress permits."); see also Bibiano v. Lynch, 834 F.3d 966, 971 (9th Cir. 2016) ("Section 1252(b)(2) is a non-jurisdictional venue statute") (collecting cases) (emphasis added); Andreiu v. Ashcroft, 253 F.3d 477, 482 (9th Cir. 2001) (en banc) (the court clarified "that § 1252(f)(2)'s standard for granting injunctive relief in removal proceedings trumps any contrary provision elsewhere in the law.").

- Matter of H-N-, 22 I&N Dec. 1039, 1040-45 (BIA 1999) (en banc) (case of a female Cambodian-American who was convicted of a particularly serious crime but "the Immigration Judge found [her] eligible for a waiver of inadmissibility, as well as for adjustment of status, and he granted her this relief from removal."); Matter of Jean, 23 I&N Dec. 373, 381 (A.G. 2002) ("Aliens, like the respondent, who have been admitted (or conditionally admitted) into the United States as refugees can seek an adjustment of status only under INA § 209."); INA § 209(c), ("The provisions of paragraphs (4), (5), and (7)(A) of section 1182(a) of this title shall not be applicable to any alien seeking adjustment of status under this section, and the Secretary of Homeland Security or the Attorney General may waive any other provision of [section 1182] ... with respect to such an alien for humanitarian purposes, to assure family unity, or when it is otherwise in the public interest.") (emphasis added); Nguyen v. Chertoff, 501 F.3d 107, 109-10 (2d Cir. 2007) (petition granted of a Vietnamese-American convicted of a particularly serious crime); City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc., 473 U.S. 432, 439 (1985) ("The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment commands that ... all persons similarly situated should be treated alike.").

- Matter of J-H-J-, 26 I&N Dec. 563 (BIA 2015) (collecting court cases) ("An alien who adjusted status in the United States, and who has not entered as a lawful permanent resident, is not barred from establishing eligibility for a waiver of inadmissibility under section 212(h) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, (2012), as a result of an aggravated felony conviction.") (emphasis added); see also De Leon v. Lynch, 808 F.3d 1224, 1232 (10th Cir. 2015) ("[Petitioner] next claims that even if he is removable, he should nevertheless have been afforded the opportunity to apply for a waiver under . Under controlling precedent from our court and the BIA's recent decision in Matter of J–H–J–, he is correct.") (emphasis added).

- Zivkovic v. Holder, 724 F.3d 894, 911 (7th Cir. 2013) ("Because [Petitioner]'s aggravated felony convictions were more than a decade old before the 1988 statute took effect, they cannot be used as a ground for removal...."); Ledezma-Galicia v. Holder, 636 F.3d 1059, 1080 (9th Cir. 2010) ("[Petitioner] is not removable by reason of being an aggravated felon, because 8 U.S.C. § 1227(a)(2)(A)(iii) does not apply to convictions, like [Petitioner]'s, that occurred prior to November 18, 1988."); but see Canto v. Holder, 593 F.3d 638, 640-42 (7th Cir. 2010) (good example of absurdity and deprivation of rights), cert. denied, 131 S.Ct. 85 (2010) (Question Presented: "Are individuals who went to trial entitled to the same relief provided in St. Cyr such that they may continue to seek waiver of deportation under Section 212(c) despite its repeal?" Here, p.3, the "15 years" argument had been completely waived).

- ("Clauses (i) and (ii) shall not apply to an alien seeking admission within a period if, prior to the date of the alien's reembarkation at a place outside the United States or attempt to be admitted from foreign contiguous territory, the Attorney General has consented to the alien's reapplying for admission.") (emphasis added).

- Rubin v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 583 U.S. ___ (2018) (Slip Opinion at 10) (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted); see also Matter of Song, 27 I&N Dec. 488, 492 (BIA 2018) ("Because the language of both the statute and the regulations is plain and unambiguous, we are bound to follow it."); Matter of Figueroa, 25 I&N Dec. 596, 598 (BIA 2011) ("When interpreting statutes and regulations, we look first to the plain meaning of the language and are required to give effect to unambiguously expressed intent. Executive intent is presumed to be expressed by the ordinary meaning of the words used. We also construe a statute or regulation to give effect to all of its provisions.") (citations omitted); Lamie v. United States Trustee, 540 U.S. 526, 534 (2004); TRW Inc. v. Andrews, 534 U.S. 19, 31 (2001) ("It is a cardinal principle of statutory construction that a statute ought, upon the whole, to be so construed that, if it can be prevented, no clause, sentence, or word shall be superfluous, void, or insignificant.") (internal quotation marks omitted); United States v. Menasche, 348 U.S. 528, 538-539 (1955) ("It is our duty to give effect, if possible, to every clause and word of a statute." (internal quotation marks omitted); NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1, 30 (1937) ("The cardinal principle of statutory construction is to save and not to destroy. We have repeatedly held that as between two possible interpretations of a statute, by one of which it would be unconstitutional and by the other valid, our plain duty is to adopt that which will save the act. Even to avoid a serious doubt the rule is the same.").

- Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., 519 U.S. 337, 341 (1997) ("The plainness or ambiguity of statutory language is determined by reference to the language itself, the specific context in which that language is used, and the broader context of the statute as a whole."); see also Matter of Dougless, 26 I&N Dec. 197, 199 (BIA 2013) ("The [Supreme] Court has also emphasized that the Chevron principle of deference must be applied to an agency’s interpretation of ambiguous statutory provisions, even where a court has previously issued a contrary decision and believes that its construction is the better one, provided that the agency's interpretation is reasonable.").

- In re JMC Telecom LLC, 416 B.R. 738, 743 (C.D. Cal. 2009) (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted) (emphasis added); see also In re Partida, 862 F.3d 909, 912 (9th Cir. 2017) ("That is the function and purpose of the 'notwithstanding' clause."); Drakes Bay Oyster Co. v. Jewell, 747 F.3d 1073, 1083 (9th Cir. 2014) ("As a general matter, 'notwithstanding' clauses nullify conflicting provisions of law."); Jones v. United States, No. 08-645C, p.4-5 (Fed. Cl. Sep. 14, 2009); Kucana v. Holder, 558 U.S. 233, 238-39 n.1 (2010); Andreiu v. Ashcroft, 253 F.3d 477, 482 (9th Cir. 2001) (en banc) (the court clarified "that § 1252(f)(2)'s standard for granting injunctive relief in removal proceedings trumps any contrary provision elsewhere in the law."); Cisneros v. Alpine Ridge Group, 508 U.S. 10, 18 (1993) (collecting cases).

- ; 26 U.S.C. § 5845; see also 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 6102; 18 U.S.C. § 927 ("Effect on State law").

- United States v. Valencia-Mendoza, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 17-30158, p.20-21 & n.4 (9th Cir. Jan. 10, 2019) (stating that courts of appeals "have held that, when determining whether a [state] offense is 'punishable' by more than one year in prison, the Supreme Court's recent cases require an examination of the maximum sentence possible under the state's mandatory sentencing guidelines.").

- Othi v. Holder, 734 F.3d 259, 264-65 (4th Cir. 2013) ("In 1996, Congress 'made major changes to immigration law' via IIRIRA.... These IIRIRA changes became effective on April 1, 1997.").

- ("The term 'lawfully admitted for permanent residence' means the status of having been lawfully accorded the privilege of residing permanently in the United States as an immigrant in accordance with the immigration laws, such status not having changed.").

- (emphasis added); see also ("The term 'national of the United States' means (A) a citizen of the United States, or (B) a person who, though not a citizen of the United States, owes permanent allegiance to the United States.") (emphasis added); ("The term 'permanent' means a relationship of continuing or lasting nature, as distinguished from temporary, but a relationship may be permanent even though it is one that may be dissolved eventually at the instance either of the United States or of the individual, in accordance with law."); ("The term 'residence' means the place of general abode; the place of general abode of a person means his principal, actual dwelling place in fact, without regard to intent."); Black's Law Dictionary at p.87 (9th ed., 2009) (defining the term "permanent allegiance" as "[t]he lasting allegiance owed to [the United States] by its citizens or [permanent resident]s.") (emphasis added); Ricketts v. Att'y Gen., 897 F.3d 491, 493-94 n.3 (3d Cir. 2018) ("Citizenship and nationality are not synonymous."); Jennings v. Rodriguez, 138 S.Ct. 830, 855-56 (2018) (Justice Thomas concurring) ("The term 'or' is almost always disjunctive, that is, the [phrase]s it connects are to be given separate meanings."); Chalmers v. Shalala, 23 F.3d 752, 755 (3d Cir. 1994) (same).

- ("The term 'removable' means—(A) in the case of an alien not admitted to the United States, that the alien is inadmissible under section 1182 of this title, or (B) in the case of an alien admitted to the United States, that the alien is deportable under section 1227 of this title."); see also Tima v. Att'y Gen., 903 F.3d 272, 277 (3d Cir. 2018) ("Section 1227 defines '[d]eportable aliens,' a synonym for removable aliens.... So § 1227(a)(1) piggybacks on § 1182(a) by treating grounds of inadmissibility as grounds for removal as well."); Galindo v. Sessions, 897 F.3d 894, 897 (7th Cir. 2018); Lolong v. Gonzales, 484 F.3d 1173, 1177 n.2 (9th Cir. 2007).

- "Destination USA: 75 million international guests visited in 2014". share.america.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- "International Visitation to the United States: A Statistical Summary of U.S. Visitation" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce. 2015. p. 2. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ("An illegal alien ... is any alien ... who is in the United States unlawfully...."); United States v. Torres, ___ F.3d ___, No. 15-10492 (9th Cir. Jan. 8, 2019).

- Melissa Etehad, ed. (July 19, 2018). "The Trump administration wants more than 400,000 people to leave the U.S. Here's who they are and why". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- Meagan Flynn, ed. (October 4, 2018). "Federal judge, citing Trump racial bias, says administration can't strip legal status from 300,000 Haitians, Salvadorans and others — for now". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- ("Benefits and status during period of temporary protected status"); Saliba v. Att'y Gen., 828 F.3d 182 (3d Cir. 2016).

- "Estimates of the Lawful Permanent Resident Population in the United States: January 2014" (PDF). James Lee; Bryan Baker. U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Retrieved 2018-06-29.

In summary, an estimated 13.2 million LPRs lived in the United States on January 1, 2014, and 8.9 million of them were eligible to naturalize.

- Khalid v. Sessions, 904 F.3d 129, 131 (2d Cir. 2018) ("[Petitioner] is a U.S. citizen and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) must terminate removal proceedings against him."); Jaen v. Sessions, 899 F.3d 182, 190 (2d Cir. 2018) (same); Anderson v. Holder, 673 F.3d 1089, 1092 (9th Cir. 2012) (same); Dent v. Sessions, 900 F.3d 1075, 1080 (9th Cir. 2018) ("An individual has third-party standing when [(1)] the party asserting the right has a close relationship with the person who possesses the right [and (2)] there is a hindrance to the possessor's ability to protect his own interests.") (quoting Sessions v. Morales-Santana, 582 U.S. ___, ___, 137 S.Ct. 1678, 1689 (2017)) (internal quotation marks omitted); Gonzalez-Alarcon v. Macias, 884 F.3d 1266, 1270 (10th Cir. 2018); Hammond v. Sessions, No. 16-3013, p.2-3 (2d Cir. Jan. 29, 2018) ("It is undisputed that Hammond's June 2016 motion to reconsider was untimely because his removal order became final in 2003.... Here, reconsideration was available only under the BIA's sua sponte authority. 8 C.F.R. 1003.2(a). Despite this procedural posture, we retain jurisdiction to review Hammond's U.S. [nationality] claim."); accord Duarte-Ceri v. Holder, 630 F.3d 83, 87 (2d Cir. 2010) ("Duarte's legal claim encounters no jurisdictional obstacle because the Executive Branch has no authority to remove a [national of the United States]."); 8 C.F.R. 239.2; see also Yith v. Nielsen, 881 F.3d 1155, 1159 (9th Cir. 2018) ("Once applicants have exhausted administrative remedies, they may appeal to a district court."); ("Request for hearing before district court").

- Ricketts v. Att'y Gen., 897 F.3d 491 (3d Cir. 2018) ("When an alien faces removal under the Immigration and Nationality Act, one potential defense is that the alien is not an alien at all but is actually a national of the United States."); ("The term 'naturalization' means the conferring of nationality of [the] [United States] upon a person after birth, by any means whatsoever.") (emphasis added); 8 U.S.C. § 1436 ("A person not a citizen who owes permanent allegiance to the United States, and who is otherwise qualified, may, if he becomes a resident of any State, be naturalized upon compliance with the applicable requirements of this subchapter...."); see also Saliba v. Att'y Gen., 828 F.3d 182, 189 (3d Cir. 2016) ("Significantly, an applicant for naturalization has the burden of proving 'by a preponderance of the evidence that he or she meets all of the requirements for naturalization.'"); In re Petition of Haniatakis, 376 F.2d 728 (3d Cir. 1967); In re Sotos' Petition, 221 F. Supp. 145 (W.D. Pa. 1963).

- Smriko v. Ashcroft, 387 F.3d 279, 287 (3d Cir. 2004) (explaining that the idea of refugees being admitted to the United States as lawful permanent residents was intentionally rejected by the U.S. Congressional Conference Committee); H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 96-781, at 21 (1980), reprinted in 1980 U.S.C.C.A.N. 160, 162; see also Matter of D-K-, 25 I&N Dec. 761, 767 (BIA 2012).

- Stanton, Ryan (May 11, 2018). "Michigan father of 4 was nearly deported; now he's a U.S. citizen". www.mlive.com. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- Sakuma, Amanda (October 24, 2014). "Lawsuit says ICE attorney forged document to deport immigrant man". MSNBC. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- "60 FR 7885: ANTI-DISCRIMINATION" (PDF). U.S. Government Publishing Office. February 10, 1995. p. 7888. Retrieved July 16, 2018. See also Zuniga-Perez v. Sessions, 897 F.3d 114, 122 (2d Cir. 2018) ("The Constitution protects both citizens and non‐citizens.") (emphasis added).

- "NBC Asian America Presents: Deported". NBC. March 16, 2017. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- "Deprivation Of Rights Under Color Of Law". U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). August 6, 2015. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

Section 242 of Title 18 makes it a crime for a person acting under color of any law to willfully deprive a person of a right or privilege protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States. For the purpose of Section 242, acts under 'color of law' include acts not only done by federal, state, or local officials within their lawful authority, but also acts done beyond the bounds of that official's lawful authority, if the acts are done while the official is purporting to or pretending to act in the performance of his/her official duties. Persons acting under color of law within the meaning of this statute include police officers, prisons guards and other law enforcement officials, as well as judges, care providers in public health facilities, and others who are acting as public officials. It is not necessary that the crime be motivated by animus toward the race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status or national origin of the victim. The offense is punishable by a range of imprisonment up to a life term, or the death penalty, depending upon the circumstances of the crime, and the resulting injury, if any.

(emphasis added). - 18 U.S.C. §§ 241–249; United States v. Lanier, 520 U.S. 259, 264 (1997) ("Section 242 is a Reconstruction Era civil rights statute making it criminal to act (1) 'willfully' and (2) under color of law (3) to deprive a person of rights protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States."); United States v. Acosta, 470 F.3d 132, 136 (2d Cir. 2006) (holding that 18 U.S.C. §§ 241 and 242 are "crimes of violence"); see also 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981–1985; et seq.; Rodriguez v. Swartz, 899 F.3d 719 (9th Cir. 2018) ("A U.S. Border Patrol agent standing on American soil shot and killed a teenage Mexican citizen who was walking down a street in Mexico."); Ziglar v. Abbasi, 582 U.S. ___ (2017) (mistreating immigration detainees); Hope v. Pelzer, 536 U.S. 730, 736-37 (2002) (mistreating prisoners); Lyttle v. United States, 867 F.Supp.2d 1256, 1270 (M.D. Ga. 2012) (case about a U.S.-born citizen deported from the United States by the ICE "as an 'alien who is convicted of an aggravated felony.'").

- 18 U.S.C. § 2441 ("War crimes").

- "Article 16". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

[The United States] shall undertake to prevent in any territory under its jurisdiction other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment which do not amount to torture as defined in article I, when such acts are committed by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.

(emphasis added). - "Chapter 11 - Foreign Policy: Senate OKs Ratification of Torture Treaty" (46th ed.). CQ Press. 1990. pp. 806–7. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

The three other reservations, also crafted with the help and approval of the Bush administration, did the following: Limited the definition of 'cruel, inhuman or degrading' treatment to cruel and unusual punishment as defined under the Fifth, Eighth and 14th Amendments to the Constitution....

(emphasis added). - Landon v. Plasencia, 459 U.S. 21, 32 (1982)

- Matter of Izatula, 20 I&N Dec. 149, 154 (BIA 1990) ("Afghanistan is a totalitarian state under the control of the [People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan], which is kept in power by the Soviet Union."); Matter of B-, 21 I&N Dec. 66, 72 (BIA 1995) (en banc) ("We further find, however, that the past persecution suffered by the applicant was so severe that his asylum application should be granted notwithstanding the change of circumstances.").

- "Cambodia: Khmer Rouge leaders guilty of genocide, court rules". Al Jazeera. November 16, 2018. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

Verdict after years of trial is first time any Khmer Rouge leaders were found guilty of genocide for 1975-79 terror.

- Federis, Marnette (March 3, 2018). "Some Vietnamese immigrants were protected from deportation, but the Trump administration may be changing that policy". Public Radio International (PRI). Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- Levin, Sam (November 10, 2017). "Detained and divided: how the US turned on Vietnamese refugees". The Guardian. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- See generally Hanna v. Holder, 740 F.3d 379, 393-97 (6th Cir. 2014) (explaining what "firm resettlement" is); Matter of A-G-G-, 25 I&N Dec. 486 (BIA 2011) (same).

- Alabama v. Bozeman, 533 U.S. 146, 153 (2001) ("The word 'shall' is ordinarily the language of command.") (internal quotation marks omitted); Kingdomware Technologies, Inc. v. United States, 579 U.S. ___, ___, 136 S.Ct. 1969, 1977 (2016) ("Unlike the word 'may,' which implies discretion, the word 'shall' usually connotes a requirement.").

- (explaining that lawful permanent residents may lawfully remain outside the United States for up to one year (or even longer) in certain situations).

- Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144, 160 (1963) (citation and internal quotation marks omitted); see also Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. 387, 395 (2012) ("Perceived mistreatment of aliens in the United States may lead to harmful reciprocal treatment of American citizens abroad.")

- Stevens, Jacqueline (June 2, 2015). "No Apologies, But Feds Pay $350K to Deported American Citizen". LexisNexis. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- "Peter Guzman and Maria Carbajal, v. United States, CV08-01327 GHK (SSx)" (PDF). U.S. District Court for the Central District of California (CDCA). www.courtlistener.com. June 7, 2010. p. 3. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 842-43 (1984).

- See generally Toor v. Lynch, 789 F.3d 1055, 1064-65 (9th Cir. 2015) ("The regulatory departure bar [(8 C.F.R. 1003.2(d))] is invalid irrespective of the manner in which the movant departed the United States, as it conflicts with clear and unambiguous statutory text.") (collecting cases); see also Blandino-Medina v. Holder, 712 F.3d 1338, 1342 (9th Cir. 2013) ("An individual who has already been removed can satisfy the case-or-controversy requirement by raising a direct challenge to the removal order."); United States v. Charleswell, 456 F.3d 347, 351 (3d Cir. 2006) (same); Kamagate v. Ashcroft, 385 F.3d 144, 150 (2d Cir. 2004) (same); Zegarra-Gomez v. INS, 314 F.3d 1124, 1127 (9th Cir. 2003) (holding that because petitioner's inability to return to the United States for twenty years as a result of his removal was "a concrete disadvantage imposed as a matter of law, the fact of his deportation did not render the pending habeas petition moot").

- ; see generally Reyes Mata v. Lynch, 576 U.S. ___, ___, 135 S.Ct. 2150, 1253 (2015); Avalos-Suarez v. Whitaker, No. 16-72773 (9th Cir. Nov. 16, 2018) (unpublished) (case remanded to the BIA which involves a legal claim over a 1993 order of deportation); Ku v. Attorney General United States, No. 17-3001, pp.7-8 & n.3 (3d Cir. 2019); Nassiri v. Sessions, No. 16-60718 (5th Cir. Dec. 14, 2017); Alimbaev v. Att'y, 872 F.3d 188, 194 (3d Cir. 2017); Agonafer v. Sessions, 859 F.3d 1198, 1202-03 (9th Cir. 2017); In re Baig, A043-589-486 (BIA Jan. 26, 2017); In re Cisneros-Ramirez, A 090-442-154 (BIA Aug. 9, 2016); In re Contreras-Largaespada, A014-701-083 (BIA Feb. 12, 2016); In re Wagner Aneudis Martinez, A043 447 800 (BIA Jan. 12, 2016); In re Vikramjeet Sidhu, A044 238 062 (BIA Nov. 30, 2011); accord Matter of A-N- & R-M-N-, 22 I&N Dec. 953 (BIA 1999) (en banc); Matter of G-N-C-, 22 I&N Dec. 281, 285 (BIA 1998) (en banc); Matter of JJ-, 21 I&N Dec. 976 (BIA 1997) (en banc).

- 8 C.F.R. 1003.2 ("Reopening or reconsideration before the Board of Immigration Appeals"); ("Burden on alien"); (explaining that "a decision that an alien is not eligible for admission to the United States is conclusive unless manifestly contrary to law...."); ("Judicial review of orders under section 1225(b)(1)").

- United States v. Bueno-Sierra, No. 17-12418, p.6-7 (6th Cir. Jan. 29, 2018) ("Rule 60(b)(1) through (5) permits a district court to set aside an otherwise final judgment on a number of specific grounds, such as mistake, newly discovered evidence, an opposing party’s fraud, or a void or satisfied judgment. Rule 60(b)(6), the catch-all provision, authorizes a judgment to be set aside for 'any other reason that justifies relief.' Rule 60(d)(3) provides that Rule 60 does not limit a district court's power to 'set aside a judgment for fraud on the court.'") (citations omitted) (unpublished); Herring v. United States, 424 F.3d 384, 386-87 (3d Cir. 2005) ("In order to meet the necessarily demanding standard for proof of fraud upon the court we conclude that there must be: (1) an intentional fraud; (2) by an officer of the court; (3) which is directed at the court itself; and (4) in fact deceives the court."); 18 U.S.C. § 371; 18 U.S.C. § 1001 (court employees (including judges and clerks) have no immunity from prosecution under this section of law); Luna v. Bell, 887 F.3d 290, 294 (6th Cir. 2018) ("Under Rule 60(b)(2), a party may request relief because of 'newly discovered evidence.'"); United States v. Handy, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 18-3086, p.5-6 (10th Cir. July 18, 2018) ("Rule 60(b)(4) provides relief from void judgments, which are legal nullities.... [W]hen Rule 60(b)(4) is applicable, relief is not a discretionary matter; it is mandatory. And the rule is not subject to any time limitation.") (citations, brackets, and internal quotation marks omitted); Mattis v. Vaughn, No. 99-6533, p.3-4 (E.D. Pa. June 4, 2018); accord Satterfield v. Dist. Att'y of Phila., 872 F.3d 152, 164 (3d Cir. 2017) ("The fact that . . . proceeding ended a decade ago should not preclude him from obtaining relief under Rule 60(b) if the court concludes that he has raised a colorable claim that he meets this threshold actual-innocence standard ...."); see also Bousley v. United States, 523 U.S. 614, 622 (1998); United States v. Olano, 507 U.S. 725, 736 (1993); Davis v. United States, 417 U.S. 333, 346-47 (1974); Gonzalez-Cantu v. Sessions, 866 F.3d 302, 306 (5th Cir. 2017) (same) (collecting cases); Pacheco-Miranda v. Sessions, No. 14-70296 (9th Cir. Aug. 11, 2017) (same).

- (stating that an LPR, especially a wrongfully deported LPR, is permitted to reenter the United States by any means whatsoever, including with a grant of "relief under section 1182(h) or 1229b(a) of this title....") (emphasis added); accord United States v. Aguilera-Rios, 769 F.3d 626, 628-29 (9th Cir. 2014) ("[Petitioner] was convicted of a California firearms offense, removed from the United States on the basis of that conviction, and, when he returned to the country, tried and convicted of illegal reentry under 8 U.S.C. § 1326. He contends that his prior removal order was invalid because his conviction ... was not a categorical match for the Immigration and Nationality Act's ('INA') firearms offense. We agree that he was not originally removable as charged, and so could not be convicted of illegal reentry."); see also Matter of Campos-Torres, 22 I&N Dec. 1289 (BIA 2000) (en banc) (A firearms offense that renders an alien removable under section 237(a)(2)(C) of the Act, (Supp. II 1996), is not one 'referred to in section 212(a)(2)' and thus does not stop the further accrual of continuous residence or continuous physical presence for purposes of establishing eligibility for cancellation of removal."); Vartelas v. Holder, 566 U.S. 257, 262 (2012); City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc., 473 U.S. 432, 439 (1985) ("The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment commands that ... all persons similarly situated should be treated alike.").

- Salmoran v. Attorney General of the U.S., ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 17-2683, p.5 n.5 (3d Cir. Nov. 26, 2018) (case involving cancellation of removal after the LPR has been physically removed from the United States on a bogus aggravated felony charge).

- ("Any reference to a term of imprisonment or a sentence with respect to an offense is deemed to include the period of incarceration or confinement ordered by a court of law regardless of any suspension of the imposition or execution of that imprisonment or sentence in whole or in part."); Matter of Cota, 23 I&N Dec. 849, 852 (BIA 2005).

- See generally, Chavez-Alvarez v. Warden York County Prison, 783 F.3d 469 (3d Cir. 2015) ("[Petitioner], a citizen of Mexico, entered the United States at a young age without inspection and later adjusted to lawful permanent resident status.... In 2000, while serving in the United States Army in South Korea, a General Court-Martial convicted him of giving false official statements.... It sentenced him to eighteen months of imprisonment. He served thirteen months in prison and was released on February 4, 2002."); Chavez-Alvarez v. Att'y Gen., 783 F.3d 478 (3d Cir. 2015); Matter of Chavez-Alvarez, 26 I&N Dec. 274 (BIA 2014).

- ("The terms 'admission' and 'admitted' mean, with respect to an alien, the lawful entry of the alien into the United States after inspection and authorization by an immigration officer.") (emphasis added); Matter of D-K-, 25 I&N Dec. 761, 765-66 (BIA 2012).

- See generally

- "Path to U.S. Citizenship". United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). January 22, 2013. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- "How to Apply for U.S. Citizenship". www.usa.gov. September 4, 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- Matter of S-O-G- & F-D-B-, 27 I&N Dec. 462 (A.G. 2018) ("Immigration judges may dismiss or terminate removal proceedings only under the circumstances expressly identified in the regulations, see 8 C.F.R. 1239.2(c), (f), or where the Department of Homeland Security fails to sustain the charges of removability against a respondent, see 8 C.F.R. 1240.12(c)."); see also Matter of G-N-C-, 22 I&N Dec. 281 (BIA 1998) (en banc).

- Jennings v. Rodriguez, 583 U.S. ___, 138 S.Ct. 830, 851 (2018); Wheaton College v. Burwell, 134 S.Ct. 2806, 2810-11 (2014) ("Under our precedents, an injunction is appropriate only if (1) it is necessary or appropriate in aid of our jurisdiction, and (2) the legal rights at issue are indisputably clear.") (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted); Lux v. Rodrigues, 561 U.S. 1306, 1308 (2010); Correctional Services Corp. v. Malesko, 534 U.S. 61, 74 (2001) (stating that "injunctive relief has long been recognized as the proper means for preventing entities from acting unconstitutionally."); Alli v. Decker, 650 F.3d 1007, 1010-11 (3d Cir. 2011) (same); Andreiu v. Ashcroft, 253 F.3d 477, 482-85 (9th Cir. 2001) (en banc) (same); see also ("Limitation on collateral attack on underlying deportation order").

- Singh v. USCIS, 878 F.3d 441, 443 (2d Cir. 2017) ("The government conceded that Singh's removal was improper.... Consequently, in May 2007, Singh was temporarily paroled back into the United States by the Attorney General, who exercised his discretion to grant temporary parole to certain aliens."); Orabi v. Att'y Gen., 738 F.3d 535, 543 (3d Cir. 2014) ("The judgment of the BIA will therefore be reversed, with instructions that the Government... be directed to return Orabi to the United States in accordance with the ICE regulations cited."); Avalos-Palma v. United States, No. 13-5481 (FLW), 2014 WL 3524758, p.3 (D.N.J. July 16, 2014) ("On June 2, 2012, approximately 42 months after the improper deportation, ICE agents effectuated Avalos-Palma's return to the United States."); In re Vikramjeet Sidhu, A044 238 062, at 1-2 (BIA Nov. 30, 2011) ("As related in his brief on appeal, the respondent was physically removed from the United States in June 2004, but subsequently returned to this country under a grant of humanitarian parole.... Accordingly, the proceedings will be terminated.") (three-member panel).

- ("Paragraph (1) shall not apply to an alien if the Attorney General determines that— ... (ii) the alien, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of the United States") (emphasis added).

- Anwari v. Attorney General of the U.S., Nos. 18-1505 & 18-2291, p.6 (3rd Cir. Nov. 6, 2018); Matter of Y-L-, A-G- & R-S-R-, 23 I&N Dec. 270, 279 (A.G. 2002) ("Although the respondents are statutorily ineligible for withholding of removal by virtue of their convictions for 'particularly serious crimes,' the regulations implementing the Convention Against Torture allow them to obtain a deferral of removal notwithstanding the prior criminal offenses if they can establish that they are 'entitled to protection' under the Convention."); ("Claims under the United Nations Convention").

- (stating that "the authority for which is specified under this subchapter to be in the discretion of the Attorney General or the Secretary of Homeland Security, other than the granting of relief under section 1158(a)....") (emphasis added).

- United States v. Vidal–Mendoza, 705 F.3d 1012, 1013-14 n.2 (9th Cir. 2013) ("Voluntary departure is not available to an alien who has been convicted of an aggravated felony.").

- Nken v. Holder, 556 U.S. 418, 443 (2009) (Justice Alito dissenting with Justice Thomas).

- United States v. Lanier, 520 U.S. 259, 264-65 n.3 (1997) (internal quotation marks omitted) (emphasis added).

- In re Juan Ignacio Ruela, A077 485 879 (BIA May 5, 2014); United States v. Pray, 373 F.3d 358, 361 (3d Cir. 2004) ("We hold that the term 'imprisonment' ... does not include parole.... A person who is on parole, although subject to some restraints on liberty, is not 'imprisoned' in the sense in which the term is usually used. For example, if a parolee were informed at the end of a parole revocation hearing that the outcome was 'imprisonment,' the parolee would not think that this meant that he was going to be returned to parole.") (citations omitted); United States v. Benz, 282 U.S. 304, 306-07 (1931); United States v. Pettus, 303 F.3d 480 (2d Cir. 2002) (regarding "street time"); Young v. Pa. Board of Probation and Parole, No. 361 C.D. 2016 (Commonwealth Court of Pa. June 12, 2018) ("However, if the Parole Board does award credit, the parolee no longer has 'time spent at liberty on parole,' i.e., 'street time.' Id.") (emphasis added); Commonwealth v. Conahan, 589 A.2d 1107, 1110 (Pa. 1991); Young v. Pa. Board of Probation and Parole, 409 A.2d 843, 846-47 (Pa. 1979) ("To attempt to equate a parole status with that of custody is to ignore reality."); accord Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471, 482 (1972).

- Garcia-Mendoza v. Holder, 753 F.3d 1165, 1169 (10th Cir. 2014).

- State v. Cole, 262 Wis.2d 167, 177, 663 N.W.2d 700 (Wis. 2003).

- United States v. Parsons, No. 15-2055, at p.10 (3d Cir. Nov. 10, 2016); accord United States v. Frias, 338 F.3d 206, 211 (3d Cir. 2003); United States v. Rodriguez-Bernal, 783 F.3d 1002, 1006 (5th Cir. 2015); United States v. Rodriguez-Arreola, 313 F.3d 1064, 1066 (8th Cir. 2002); see also ("In the case of a person who violates section 922(g) ... the court shall not suspend the sentence of, or grant a probationary sentence to, such person ....") (emphasis added); 42 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 9756(b) ("The court shall impose a minimum sentence of confinement which shall not exceed one-half of the maximum sentence imposed.") (emphasis added).

- United States v. Graham, 169 F.3d 787, 792 (3d Cir. 1999); see also Francis v. Reno, 269 F.3d 162, 167-71 (3d Cir. 2001)

- ; ; see also, generally Arias v. Lynch, 834 F.3d 823, 831 (7th Cir. 2016); Flores-Molina v. Sessions, 850 F.3d 1150, 1171-72 (10th Cir. 2017) (collecting cases); Ildefonso-Candelario v. Att'y Gen., 866 F.3d 102, 105-06 n.4 (3d Cir. 2017); Lozano-Arredondo v. Sessions, 866 F.3d 1082, 1086 (9th Cir. 2017); Romero v. Sessions, Nos. 16-73655, 17-70848 (9th Cir. June 1, 2018) (unpublished); Garcia-Martinez v. Sessions, 886 F.3d 1291, 1294 (9th Cir. 2018); Beltran-Tirado v. INS, 213 F.3d 1179, 1183 (9th Cir. 2000); Matter of Serna, 20 I&N Dec. 579, 584 (BIA 1992); Matter of Espinosa, 10 I&N Dec. 98 (BIA 1962).

- Alabama v. Shelton, 535 U.S. 654, 670 n.10 (2002) ("In Pennsylvania, for example, ... only those charged with 'summary offenses' (violations not technically considered crimes and punishable by no more than 90 days' imprisonment, ... may receive a suspended sentence uncounseled. (Typical 'summary offenses' in Pennsylvania include the failure to return a library book within 30 days, ... and fishing on a Sunday [.])" (citations omitted).

- United States v. Olano, 507 U.S. 725, 732 (1993).

- Edwards v. Sessions, No. 17-87, p.3 (2d Cir. 2018) ("In removal proceedings involving an LPR, the government bears the burden of proof, which it must meet by adducing clear, unequivocal, and convincing evidence that the facts alleged as grounds for deportation are true.") (internal quotation marks omitted) (summary order); accord 8 C.F.R. 1240.46(a); ; Mondaca-Vega v. Lynch, 808 F.3d 413, 429 (9th Cir. 2015) ("The burden of proof required for clear, unequivocal, and convincing evidence is greater than the burden of proof required for clear and convincing evidence."); Ward v. Holder, 733 F.3d 601, 604–05 (6th Cir. 2013); United States v. Thompson-Riviere, 561 F.3d 345, 349 (4th Cir. 2009) ("To convict him of this offense, the government bore the burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that (inter alia) he is an 'alien,' which means he is 'not a citizen or national of the United States,'" (citations omitted); Francis v. Gonzales, 442 F.3d 131, 138 (2d Cir. 2006); Matter of Pichardo, 21 I&N Dec. 330, 333 (BIA 1996) (en banc); Berenyi v. Immigration Director, 385 U.S. 630, 636-37 (1967) ("When the Government seeks to strip a person of [United States nationality] already acquired, or deport a resident alien and send him from our shores, it carries the heavy burden of proving its case by 'clear, unequivocal, and convincing evidence.' . . . [T]hat status, once granted, cannot lightly be taken away....") (footnotes omitted); Woodby v. INS, 385 U.S. 276, 285 (1966); Chaunt v. United States, 364 U.S. 350, 353 (1960).

- See generally United States v. Barret, ___ F.3d ___, No. 14-2641 (2d Cir. 2018); United States v. Pereira-Gomez, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 17-952, p.6 note 4 (2d Cir. 2018) (defining "crime of violence").

- Lopez v. Gonzales, 549 U.S. 47 (2006) ("The question raised is whether conduct made a felony under state law but a misdemeanor under the Controlled Substances Act is a "felony punishable under the Controlled Substances Act." . We hold it is not.") (emphasis added).

- United States v. Chapa-Garza, 243 F.3d 921, 928 (5th Cir. 2001).

- Francis v. Reno, 269 F.3d 162, 171-75 (3d Cir. 2001).

- Popal v. Gonzales, 416 F.3d 249 (3d Cir. 2005); see also Fernandez-Ruiz v. Gonzales 466 F.3d 1121, 1129 (9th Cir. 2006) (en banc); but see Singh v. Gonzales, 432 F.3d 533, 539 (3d Cir. 2006).

- Dent v. Sessions, 900 F.3d 1075, 1085 (9th Cir. 2018); see also Mateo v. Att'y Gen., 870 F.3d 228 (3d Cir. 2017) (same).

- ("Cancellation of removal for certain permanent residents"); ("Cancellation of removal and adjustment of status for certain nonpermanent residents") see also ("Any alien (including an alien crewman) in and admitted to the United States shall, ... be removed if the alien is within one or more of the following classes of [remov]able aliens:.... Any alien who at the time of ... adjustment of status was within one or more of the classes of aliens inadmissible by the law existing at such time [or] who is present in the United States in violation of th[e] [INA] or any other law of the United States, ... is [remov]able."); but see Matter of Ortega-Lopez, 27 I&N Dec. 382, 391-98 (BIA 2018) (coming to a conflicting conclusion); Matter of Velasquez-Rios, 27 I&N Dec. 470 (BIA 2018) (same).

- Gonzalez v. Secretary of DHS, 678 F.3d 254, 160-61 (3d Cir. 2012) ("Declaratory relief, in the form of a judgment regarding the lawfulness of the denial of naturalization, permits the alien a day in court, as required by § 1421(c), while not upsetting the priority of removal over naturalization established in § 1429 because it affects the record for—but not the priority of—removal proceedings, thereby preserving both congressionally mandated goals, a de novo review process and the elimination of the race to the courthouse.")

- ("A person may file an application for naturalization other than in the office of the Attorney General, and an oath of allegiance administered other than in a public ceremony before the Attorney General or a court, if the Attorney General determines that the person has an illness or other disability which... is of a nature which so incapacitates the person as to prevent him from personally appearing.") (emphasis added); see also ("The Attorney General may, in his discretion, waive a personal investigation in an individual case or in such cases or classes of cases as may be designated by him.") (emphasis added).

- "Suspected Islamic State member accused of killing police officer in Iraq arrested in Sacramento, where he settled as a refugee". Alene Tchekmedyian. Los Angeles Times. August 15, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- Perez-Guzman v. Lynch, 835 F.3d 1066, 1075 (9th Cir. 2016) ("When two statutes come into conflict, courts assume Congress intended specific provisions to prevail over more general ones....").

- Maharaj v. Ashcroft, 295 F.3d 963, 966 (9th Cir. 2002).

- "NBC Asian America Presents: Deported". NBC. March 16, 2017. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- NLRB v. SW General, Inc., 580 U.S. ___, ___, 137 S.Ct. 929, 939 (2017).

- "Board of Immigration Appeals". U.S. Dept. of Justice. March 16, 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-05.