Waiver of inadmissibility (United States)

Waiver of inadmissibility under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) is a legal remedy available to every person found to be "removable" from the United States.[1] It is statutorily linked to cancellation of removal, which is another form of relief under the INA that effectively operates parallel to waiver of inadmissibility.[2][3]

Every American (national of the United States) is manifestly and automatically qualified for waiver of inadmissibility.[4][5][6][7] Similarly, every person who has been firmly resettled in the United States as a refugee is statutorily entitled to waiver of inadmissibility.[8][9][10] All other people must request this relief by filing Form I-601 ("Application for Waiver of Grounds of Inadmissibility").[11]

Background

The INA, which was enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1952, states that "[t]he term 'alien' means any person not a citizen or national of the United States."[15] The terms "inadmissible aliens" and "deportable aliens" are synonymous,[1] which mainly refer to the INA violators among the 75 million foreign nationals who are admitted as visitors each year,[16][17] the 12 million or so illegal aliens,[18] and the INA violators among the 400,000 foreign nationals who possess the temporary protected status (TPS).[19]

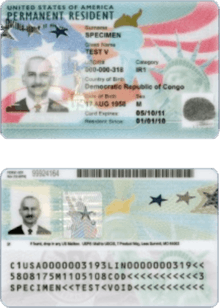

"Only aliens are subject to removal."[20] A lawful permanent resident (LPR) can either be an "alien" or a "national of the United States" (American),[12][13][14] which requires a case-by-case analysis and depends mainly on the number of continuous years he or she has spent in the United States as a green card holder (legal immigrant).[3][4][5]

U.S. Presidents and the U.S. Congress have expressly favored some "legal immigrants"[21] because they were admitted to the United States as refugees,[22][8][9][10] i.e., people who escaped from genocides and have absolutely no safe country of permanent residence other than the United States.[23] Removing such protected people from the United States constitutes a grave international crime,[24][25][26][27][28][21][29] especially if they qualify as Americans or have physically and continuously resided in the United States for at least 10 years without committing any offense that triggers removability.[4][5]

Before the 1996 enactment of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA),[30] U.S. President Bill Clinton had issued an important directive in which he expressly stated the following:

Our efforts to combat illegal immigration must not violate the privacy and civil rights of legal immigrants and U.S. citizens. Therefore, I direct the Attorney General, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and other relevant Administration officials to vigorously protect our citizens and legal immigrants from immigration-related instances of discrimination and harassment. All illegal immigration enforcement measures shall be taken with due regard for the basic human rights of individuals and in accordance with our obligations under applicable international agreements. (emphasis added).[21][31]

Waiver of inadmissibility for people who qualify as refugees or asylum seekers

An alien may be inadmissible to the United States for a variety of reasons, which are all described under paragraphs (1) to (10) of 8 U.S.C. § 1182(a).[32] In 1980, Congress and the Carter administration enacted the Refugee Act, which approved 50,000 international refugees to be firmly resettled in the United States each year.[22][33][3]

Congress had intentionally provided to every refugee a special waiver of inadmissibility under 8 U.S.C. §§ 1157(c)(3) and 1159(c), even if the refugee has been convicted of an aggravated felony or a particularly serious crime.[8][9][10] An asylum seeker may also obtain a waiver of inadmissibility pursuant to § 1159(c),[34][35][3] but an asylum seeker may be disqualified if he or she has been convicted of a particularly serious crime,[36] unless its "term of imprisonment was completed within the previous 15 years."[37]

Section 1157(c)(1) provides the following:

Subject to the numerical limitations established pursuant to subsections (a) and (b), the Attorney General may, in the Attorney General's discretion and pursuant to such regulations as the Attorney General may prescribe, admit any refugee who is not firmly resettled in any foreign country, is determined to be of special humanitarian concern to the United States, and is admissible (except as otherwise provided under paragraph (3)) as an immigrant under this chapter.[22][33]

In this regard, paragraph (3) expressly provides the following:

The provisions of paragraphs (4), (5), and (7)(A) of section 1182(a) of this title shall not be applicable to any alien seeking admission to the United States under [section 1157(c)], and the Attorney General may waive any other provision of [section 1182] . . . with respect to such an alien for humanitarian purposes, to assure family unity, or when it is otherwise in the public interest.[38][3]

The above legal finding "is consistent with one of the most basic interpretive canons, that a statute should be construed so that effect is given to all its provisions, so that no part will be inoperative or superfluous, void or insignificant."[39] It clearly demonstrates that Congress intentionally made available a special statutory and mandatory relief exclusively for refugees.[22] If Congress wanted to treat refugees the same as all other aliens, it would have repealed §§ 1157(c)(3) and 1159(c) instead of amending them in 1996 and then in 2005.[30] Under the well known Chevron doctrine, "[i]f the intent of Congress is clear, that is the end of the matter, for the court as well as the [Attorney General] must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress."[40]

Reasons for people to become inadmissible to the United States

Health related grounds

- Communicable diseases of public health significance. This currently includes Class A Tuberculosis, Chancroid, Gonorrhea, Granuloma inguinale, Lymphogranuloma venereum, Syphilis, Leprosy or any other communicable disease as determined by the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services.[41] Individuals diagnosed with these illnesses may apply for a waiver inadmissibility.[42]

- Refusal of required vaccinations

- Physical or mental disorders and associated harmful behaviors[43]

Criminal grounds

- Crimes involving moral turpitude (other than a purely political offense)[42]

- A controlled substance violation according to the laws and regulations of any country or U.S. state[42]

- Two or more summary convictions not including DUI's, Dangerous Driving or General Assault, or 1 Indictable conviction.[42]

- Prostitution and commercialized vice

- A serious criminal activity for which immunity from prosecution has been received

Security and related grounds

- Spies, saboteurs or terrorists

- Voluntary members of Communist or other totalitarian parties

- Members of Nazism

Aliens inadmissible under section 212(a)(3)(B) of the INA have

- been involved in a current or past terrorist group

- contributed finances to a current or past terrorist group

- relatives whom are or have been involved in a current or past terrorist group

- provided medical assistance to a past or current terrorist group

- been child soldiers, sex slaves, or trafficked persons forced to contribute to a current or past terrorist group

- been forced to aid a past or current terrorist group

Illegal entrants and immigration violators

There are several circumstances under which illegal entrants and immigration violators may apply for a Waiver of Inadmissibility:

- Aliens who enter the United States without being admitted or paroled at a port of entry (EWI - Entry Without Inspection) or who overstay a valid visa begin to accrue unlawful presence after the illegal entry, or the period of authorized stay expires.[44]

- Aliens who knowingly or willfully made misrepresentations or committed fraud in order to obtain an immigration benefit or benefit under the INA, may apply for a waiver of inadmissibility on Form I-601.[45]

- Aliens previously deported or given expedited removal must also file Form I-212, Application for Permission to Reapply for Admission (if eligible).[46]

- Aliens unlawfully present in the United States for an aggregate period of one (1) year who have exited the United States and re-entered without inspection (EWI) are not eligible to file Form I-601 to waive their unlawful presence.[47]

Miscellaneous grounds

- practicing polygamists

- guardians accompanying helpless aliens

- International child abductors and relatives supporting abductors

- Former U.S. citizens found by the Attorney General to have renounced citizenship for the purpose of avoiding taxation (the currently-unenforced Reed Amendment)[48][49]

Requirements for approval of waiver of inadmissibility

Unlawful presence (3/10 year bar)

- If the applicant is inadmissible because he or she has been unlawfully present in the United States for more than 180 days (3-year bar) or one year (10-year bar), they may apply for a waiver of inadmissibility.[42]

- It is important to note that an applicant MAY NOT BE ELIGIBLE to apply for waiver of inadmissibility if he or she was unlawfully present in the United States for more than one year, left the United States, then returned without being admitted or paroled (EWI).[50]

- The applicant must establish that his or her U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident spouse, parent, or the K visa petitioner would suffer extreme hardship if the application were denied.[42]

- There are special instructions for TPS and VAWA self-petitioners applying for a waiver of this ground of inadmissibility.[42]

Criminal grounds

- The applicant may apply for a waiver of inadmissibility if he or she has been found to be inadmissible for: (1) a crime involving moral turpitude (other than a purely political offense); (2) a controlled substance violation according to the laws and regulations of any country; (3) two or more summary convictions (other than DUI's dangerous driving or general assault), or one or more indictable convictions; (4) prostitution; (5) unlawful commercialized vice whether or not related to prostitution; or (6) being an alien involved in serious criminal activity, who has asserted immunity from prosecution.[42]

- The applicant must establish that he or she is inadmissible only because of participation in prostitution (including having procured others for prostitution or having received the proceeds of prostitution), but has been rehabilitated and his or her admission will not be contrary to the national welfare, safety or security of the United States;[42] OR

- At least 15 years have passed since the activity or event that made the applicant inadmissible, they have been rehabilitated and that their admission to the United States (or issuance of the immigrant visa) will not be contrary to the national welfare, safety or security of the United States;[42] OR

- The applicant's qualifying U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident spouse, son, daughter, parent or K visa petitioner would experience extreme hardship if the applicant were denied admission; OR

- The applicant is an approved VAWA (Violence Against Women Act) self-petitioner.

- The U.S. Attorney General will not favorably exercise discretion for a waiver to consent to the reapplication to the United States (or adjustment of status) in cases involving violent or dangerous crimes except in extraordinary circumstances or cases where the applicant clearly demonstrates that denial of the application would result in "exceptional and extremely unusual hardship."[51]

Fraud or misrepresentation

- If the applicant is inadmissible because he or she has sought to procure an immigration benefit by fraud or misrepresenting a material fact [INA Section 212(a)(6)(C)(i)], they may apply for a waiver of inadmissibility.[42]

- The applicant must demonstrate that his or her qualifying U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident spouse, parent or the K visa petitioner would experience extreme hardship if the applicant were denied admission or the applicant is a VAWA self-petitioner and the applicant, their U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident parent or child would experience extreme hardship if the applicant were denied admission to the U.S.[42]

Health related grounds of inadmissibility

- An applicant's petition may be approved if he or she is the spouse, parent, unmarried son or daughter, or the minor unmarried lawfully adopted child of a U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident, or of an alien who has been issued an immigrant visa, or the fiancé(e) of a U.S. citizen or the fiancé(e)'s child; or if they are a VAWA self-petitioner.[42]

- Please note that there are additional application requirements for individuals who are inadmissible due to diagnosis with Class A Tuberculosis, HIV, or a "Physical or Mental Disorder and Associated Harmful Behavior".[42][52]

- A blanket waiver of required vaccinations can be given by the civil surgeon for vaccinations that are not medically appropriate at the time of examination. Applicants with religious or moral objections to all vaccinations may submit proof and apply for a waiver.

Immigrant membership in a totalitarian party

- If the applicant is inadmissible because he or she was a member of, or affiliated with, the Communist or any other totalitarian party, they may apply for a waiver of inadmissibility.[42][53]

- A waiver may be granted for humanitarian purposes, to assure family unity, or when it is in the public interest if the applicant is the parent, spouse, son, daughter, brother or sister of a U.S. citizen, or a spouse, son or daughter of a lawful permanent resident, or the fiancé(e) of a U.S. citizen.[42] The applicant must also not be deemed a threat to the security of the United States.[42]

Alien smuggling

- If the applicant is inadmissible because he or she has engaged in alien smuggling,[54] they may apply for a Waiver of Ground of Inadmissibility on Form I-601 ONLY IF they have encouraged, induced, assisted, abetted or aided an individual who at the time of the action was their spouse, parent, son or daughter (and no other individual) to enter the United States in violation of the law.[42]

- Also, the applicant must be either: (1) a legal permanent resident who temporarily proceeded abroad, not under an order of removal, and who is otherwise admissible to the U.S. as a returning resident; or (2) seeking admission or adjustment of status as an immediate relative, a first, second or third preference immigrant, or as the fiancé(e) (or his or her children) of a U.S. citizen.[42]

- A waiver under this section may be granted for humanitarian reasons, to assure family unity, or when it is otherwise in the public interest.

Procedures

Applicants may download Form I-601 ("Application for Waiver of Grounds of Inadmissibility") from the USCIS website.[11] Depending on whether an applicant is applying for an immigrant visa or adjustment of status, Form I-601 may be filed at the consular office, USCIS office, or in the immigration court considering the immigrant visa or adjustment of status application.[11] It may also be filed with the BIA.[55] The filing fee for Form I-601 is currently $930.

See also

References

This article is mostly based on statutory and case law of the United States.

- ("The term 'removable' means—(A) in the case of an alien not admitted to the United States, that the alien is inadmissible under section 1182 of this title, or (B) in the case of an alien admitted to the United States, that the alien is deportable under section 1227 of this title."); see also Tima v. Attorney General of the U.S., ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 16-4199, p.11 (3d Cir. Sept. 6, 2018) ("Section 1227 defines '[d]eportable aliens,' a synonym for removable aliens.... So § 1227(a)(1) piggybacks on § 1182(a) by treating grounds of inadmissibility as grounds for removal as well."); Galindo v. Sessions, 897 F.3d 894, ___, No. 17-1253, p.4-5 (7th Cir. July 31, 2018).

- See, e.g., Salmoran v. Attorney General of the U.S., ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 17-2683, p.5 n.5 (3d Cir. Nov. 26, 2018) (case involving cancellation of removal after an LPR has been deported based on incorrect aggravated felony charge).

- (the subparagraph as a whole clearly implicates that wrongfully deported green card holders are permitted to reenter the United States by any means whatsoever without needing to apply for admission); accord United States v. Aguilera-Rios, 769 F.3d 626, 628-29 (9th Cir. 2014) ("[The petitioner] was convicted of a California firearms offense, removed from the United States on the basis of that conviction, and, when he returned to the country, tried and convicted of illegal reentry under 8 U.S.C. § 1326. He contends that his prior removal order was invalid because his conviction ... was not a categorical match for the Immigration and Nationality Act's ('INA') firearms offense. We agree that he was not originally removable as charged, and so could not be convicted of illegal reentry."); see also Matter of Campos-Torres, 22 I&N Dec. 1289 (BIA 2000) (en banc) (A firearms offense that renders an alien removable under section 237(a)(2)(C) of the Act, (Supp. II 1996), is not one 'referred to in section 212(a)(2)' and thus does not stop the further accrual of continuous residence or continuous physical presence for purposes of establishing eligibility for cancellation of removal."); Vartelas v. Holder, 566 U.S. 257, 262 (2012).

- Ricketts v. Att'y Gen., 897 F.3d 491 (3d Cir. 2018) ("When an alien faces removal under the Immigration and Nationality Act, one potential defense is that the alien is not an alien at all but is actually a national of the United States."); Mohammadi v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 782 F.3d 9, 15 (D.C. Cir. 2015) ("The sole such statutory provision that presently confers United States nationality upon non-citizens is 8 U.S.C. § 1408."); see also 8 U.S.C. § 1436 ("A person not a citizen who owes permanent allegiance to the United States, and who is otherwise qualified, may, if he becomes a resident of any State, be naturalized upon compliance with the applicable requirements of this subchapter...."); ("The term 'naturalization' means the conferring of [United States nationality] upon a person after birth, by any means whatsoever.") (emphasis added); Saliba v. Att’y Gen., 828 F.3d 182, 189 (3d Cir. 2016) ("Significantly, an applicant for naturalization has the burden of proving 'by a preponderance of the evidence that he or she meets all of the requirements for naturalization.'").

- Khalid v. Sessions, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 16‐3480, p.6 (2d Cir. Sept. 13, 2018) ("Khalid is a U.S. citizen and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) must terminate removal proceedings against him."); see also Jaen v. Sessions, 899 F.3d 182 (2d Cir. 2018) (case involving an American in removal proceedings); Anderson v. Holder, 673 F.3d 1089, 1092 (9th Cir. 2012) (same); Dent v. Sessions, ___ F.3d. ___, ___, No. 17-15662, p.10-11 (9th Cir. Aug. 17, 2018) ("An individual has third-party standing when [(1)] the party asserting the right has a close relationship with the person who possesses the right [and (2)] there is a hindrance to the possessor's ability to protect his own interests.") (quoting Sessions v. Morales-Santana, 582 U.S. ___, ___, 137 S.Ct. 1678, 1689 (2017)) (internal quotation marks omitted); Yith v. Nielsen, 881 F.3d 1155, 1159 (9th Cir. 2018) ("Once applicants have exhausted administrative remedies, they may appeal to a district court."); Gonzalez-Alarcon v. Macias, 884 F.3d 1266, 1270 (10th Cir. 2018); Hammond v. Sessions, No. 16-3013, p.2-3 (2d Cir. Jan. 29, 2018) ("It is undisputed that Hammond's June 2016 motion to reconsider was untimely because his removal order became final in 2003. . . . Here, reconsideration was available only under the BIA's sua sponte authority. 8 C.F.R. 1003.2(a). Despite this procedural posture, we retain jurisdiction to review Hammond's U.S. [nationality] claim."); accord Duarte-Ceri v. Holder, 630 F.3d 83, 87 (2d Cir. 2010) ("Duarte's legal claim encounters no jurisdictional obstacle because the Executive Branch has no authority to remove [Americans].").

- Finnegan, William (April 29, 2013). "The Deportation Machine". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

A citizen trapped in the system.

- Stevens, Jacqueline (June 2, 2015). "No Apologies, But Feds Pay $350K to Deported American Citizen". LexisNexis. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- Matter of H-N-, 22 I&N Dec. 1039, 1040-45 (BIA 1999) (en banc) (case of a female Cambodian-American who was convicted of a particularly serious crime but "the Immigration Judge found [her] eligible for a waiver of inadmissibility, as well as for adjustment of status, and he granted her this relief from removal."); Matter of Jean, 23 I&N Dec. 373, 381 (A.G. 2002) ("Aliens, like the respondent, who have been admitted (or conditionally admitted) into the United States as refugees can seek an adjustment of status only under INA § 209."); INA § 209(c), ("The provisions of paragraphs (4), (5), and (7)(A) of section 1182(a) of this title shall not be applicable to any alien seeking adjustment of status under this section, and the Secretary of Homeland Security or the Attorney General may waive any other provision of [section 1182] ... with respect to such an alien for humanitarian purposes, to assure family unity, or when it is otherwise in the public interest.") (emphasis added); see also Nguyen v. Chertoff, 501 F.3d 107, 109-10 (2d Cir. 2007) (petition granted of a Vietnamese-American convicted of a particularly serious crime); City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc., 473 U.S. 432, 439 (1985) ("The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment commands that ... all persons similarly situated should be treated alike.").

- Matter of J-H-J-, 26 I&N Dec. 563 (BIA 2015) (collecting court cases) ("An alien who adjusted status in the United States, and who has not entered as a lawful permanent resident, is not barred from establishing eligibility for a waiver of inadmissibility under section 212(h) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, (2012), as a result of an aggravated felony conviction.") (emphasis added); see also De Leon v. Lynch, 808 F.3d 1224, 1232 (10th Cir. 2015) ("Mr. Obregon next claims that even if he is removable, he should nevertheless have been afforded the opportunity to apply for a waiver under . Under controlling precedent from our court and the BIA's recent decision in Matter of J–H–J–, he is correct.") (emphasis added).

- "Board of Immigration Appeals". U.S. Dept. of Justice. March 16, 2018. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

BIA decisions are binding on all DHS officers and immigration judges unless modified or overruled by the Attorney General or a federal court.

See also 8 C.F.R. 1003.1(g) ("Decisions as precedents.") (eff. 2018); Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310, 362 (2010) ("Our precedent is to be respected unless the most convincing of reasons demonstrates that adherence to it puts us on a course that is sure error."); Al-Sharif v. United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, 734 F.3d 207, 212 (3d Cir. 2013) (en banc) (same); Miller v. Gammie, 335 F.3d 889, 899 (9th Cir. 2003) (en banc) (same). - 8 C.F.R. 212.7(a)(1); see also "I-601, Application for Waiver of Grounds of Inadmissibility". United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). April 11, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- "Estimates of the Lawful Permanent Resident Population in the United States: January 2014" (PDF). James Lee; Bryan Baker. U.S. Dept. of Homeland Security (DHS). June 2017. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- Stanton, Ryan (May 11, 2018). "Michigan father of 4 was nearly deported; now he's a U.S. citizen". www.mlive.com. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- Sakuma, Amanda (October 24, 2014). "Lawsuit says ICE attorney forged document to deport immigrant man". MSNBC. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- (emphasis added); see also ("The term 'national of the United States' means (A) a citizen of the United States, or (B) a person who, though not a citizen of the United States, owes permanent allegiance to the United States.") (emphasis added); Jennings v. Rodriguez, 138 S.Ct. 830, 855-56 (2018) (Justice Thomas concurring) ("The term 'or' is almost always disjunctive, that is, the [phrase]s it connects are to be given separate meanings.").

- "Destination USA: 75 million international guests visited in 2014". share.america.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- "International Visitation to the United States: A Statistical Summary of U.S. Visitation" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce. 2015. p. 2. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ("An illegal alien ... is any alien ... who is in the United States unlawfully....").

- ("Benefits and status during period of temporary protected status"); Saliba v. Att’y Gen., 828 F.3d 182 (3d Cir. 2016); see also Melissa Etehad, ed. (July 19, 2018). "The Trump administration wants more than 400,000 people to leave the U.S. Here's who they are and why". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Matter of Navas-Acosta, 23 I&N Dec. 586 (BIA 2003).

- "60 FR 7885: ANTI-DISCRIMINATION" (PDF). U.S. Government Publishing Office. February 10, 1995. p. 7888. Retrieved July 16, 2018. See also Zuniga-Perez v. Sessions, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 17-996, p.11 (2d Cir. July 25, 2018) ("The Constitution protects both citizens and non‐citizens.") (emphasis added).

- INA § 207(c), ; see also ("The term 'refugee' means (A) any person who is outside any country of such person’s nationality or, in the case of a person having no nationality, is outside any country in which such person last habitually resided, and who is unable ... to return to, and is unable ... to avail himself or herself of the protection of, that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion....") (emphasis added); Mashiri v. Ashcroft, 383 F.3d 1112, 1120 (9th Cir. 2004) ("Persecution may be emotional or psychological, as well as physical.").

- See, e.g., Matter of Izatula, 20 I&N Dec. 149, 154 (BIA 1990) ("Afghanistan is a totalitarian state under the control of the [People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan], which is kept in power by the Soviet Union."); Matter of B-, 21 I&N Dec. 66, 72 (BIA 1995) (en banc) ("We further find, however, that the past persecution suffered by the applicant was so severe that his asylum application should be granted notwithstanding the change of circumstances.").

- "Deprivation Of Rights Under Color Of Law". U.S. Department of Justice. August 6, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

Section 242 of Title 18 makes it a crime for a person acting under color of any law to willfully deprive a person of a right or privilege protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States. For the purpose of Section 242, acts under 'color of law' include acts not only done by federal, state, or local officials within their lawful authority, but also acts done beyond the bounds of that official's lawful authority, if the acts are done while the official is purporting to or pretending to act in the performance of his/her official duties. Persons acting under color of law within the meaning of this statute include police officers, prisons guards and other law enforcement officials, as well as judges, care providers in public health facilities, and others who are acting as public officials. It is not necessary that the crime be motivated by animus toward the race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status or national origin of the victim. The offense is punishable by a range of imprisonment up to a life term, or the death penalty, depending upon the circumstances of the crime, and the resulting injury, if any.

(emphasis added). - 18 U.S.C. §§ 241–249; United States v. Lanier, 520 U.S. 259, 264 (1997) ("Section 242 is a Reconstruction Era civil rights statute making it criminal to act (1) 'willfully' and (2) under color of law (3) to deprive a person of rights protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States."); United States v. Acosta, 470 F.3d 132, 136 (2d Cir. 2006); United States v. Maravilla, 907 F.2d 216 (1st Cir. 1990) (U.S. immigration officers kidnapped, robbed and murdered a visiting foreign businessman); United States v. Otherson, 637 F.2d 1276 (9th Cir. 1980), cert. denied, 454 U.S. 840 (1981), (U.S. immigration officer convicted of serious federal crimes); see also 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981–1985 et seq.; Rodriguez v. Swartz, 899 F.3d 719 (9th Cir. 2018) ("A U.S. Border Patrol agent standing on American soil shot and killed a teenage Mexican citizen who was walking down a street in Mexico."); Ziglar v. Abbasi, 582 U.S. ___ (2017) (mistreating immigration detainees); Hope v. Pelzer, 536 U.S. 730, 736-37 (2002) (mistreating prisoners).

- 18 U.S.C. § 2441 ("War crimes").

- "Article 16". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

[The United States] shall undertake to prevent in any territory under its jurisdiction other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment which do not amount to torture as defined in article I, when such acts are committed by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.

- "Chapter 11 - Foreign Policy: Senate OKs Ratification of Torture Treaty" (46th ed.). CQ Press. 1990. pp. 806–7. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

The three other reservations, also crafted with the help and approval of the Bush administration, did the following: Limited the definition of 'cruel, inhuman or degrading' treatment to cruel and unusual punishment as defined under the Fifth, Eighth and 14th Amendments to the Constitution....

(emphasis added). - Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144, 160 (1963) ("Deprivation of [nationality]—particularly American [nationality], which is one of the most valuable rights in the world today—has grave practical consequences.") (citation and internal quotation marks omitted); see also Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. 387, 395 (2012) ("Perceived mistreatment of aliens in the United States may lead to harmful reciprocal treatment of American citizens abroad.").

- Othi v. Holder, 734 F.3d 259, 264-65 (4th Cir. 2013) ("In 1996, Congress 'made major changes to immigration law' via IIRIRA. . . . These IIRIRA changes became effective on April 1, 1997.").

- Alabama v. Bozeman, 533 U.S. 146, 153 (2001) ("The word 'shall' is ordinarily the language of command.") (internal quotation marks omitted).

- ("Classes of aliens ineligible for visas or admission").

- See generally Hanna v. Holder, 740 F.3d 379 (6th Cir. 2014) (discussing firm resettlement); Matter of A-G-G-, 25 I&N Dec. 486 (BIA 2011) (same).

- "After an applicant has been granted asylum, 8 U.S.C. § 1159, governs the process by which an asylee may apply for an adjustment of citizenship status to 'permanent resident.'" Khan v. Johnson, 160 F.Supp.3d 1199, 1201-02 (C.D. Cal. 2016). "Under this section, the Secretary of Homeland Security or the Attorney General may, in their discretion, adjust to permanent resident the status of any alien granted asylum who, inter alia, has been physically present in the United States for at least one year after being granted asylum, continues to be a refugee within the meaning of section 1101(a)(42)(A), and is admissible (except as otherwise provided under subsection (c) of this section) as an immigrant under this chapter at the time of examination for adjustment of such alien." Id. (internal quotation marks and citation omitted). "Subsection (c), in turn, refers to section 1182, which defines ten categories of individuals who are ineligible for admission to the United States." Id.

- Matter of B-R-, 26 I&N Dec. 119, 122 (BIA 2013) ("The core regulatory purpose of asylum . . . is . . . to protect refugees with nowhere else to turn.") (brackets and internal quotation marks omitted).

- INA § 208(b)(2), ("Paragraph (1) shall not apply to an alien if the Attorney General determines that— ... (ii) the alien, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of the United States...."); Matter of G-G-S-, 26 I&N Dec. 339, 347 n.6 (BIA 2014); see also Nken v. Holder, 556 U.S. 418, 431 (2009) ("[W]here Congress includes particular language in one section of a statute but omits it in another section of the same Act, it is generally presumed that Congress acts intentionally and purposely in the disparate inclusion or exclusion.") (internal quotation marks omitted).

- ("The term [aggravated felony] applies to an offense described in this paragraph whether in violation of Federal or State law and applies to such an offense in violation of the law of a foreign country for which the term of imprisonment was completed within the previous 15 years.").

- (emphasis added); see also Jennings v. Rodriguez, 138 S.Ct. 830, 855-56 (2018) (Justice Thomas concurring) ("The term 'or' is almost always disjunctive, that is, the [phrase]s it connects are to be given separate meanings.").

- Rubin v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 583 U.S. ___ (2018) (Slip Opinion at 10) (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted); see also Matter of Song, 27 I&N Dec. 488, 492 (BIA 2018) ("Because the language of both the statute and the regulations is plain and unambiguous, we are bound to follow it."); Matter of Figueroa, 25 I&N Dec. 596, 598 (BIA 2011) ("When interpreting statutes and regulations, we look first to the plain meaning of the language and are required to give effect to unambiguously expressed intent. Executive intent is presumed to be expressed by the ordinary meaning of the words used. We also construe a statute or regulation to give effect to all of its provisions.") (citations omitted); Lamie v. United States Trustee, 540 U.S. 526, 534 (2004); TRW Inc. v. Andrews, 534 U.S. 19, 31 (2001) ("It is a cardinal principle of statutory construction that a statute ought, upon the whole, to be so construed that, if it can be prevented, no clause, sentence, or word shall be superfluous, void, or insignificant.") (internal quotation marks omitted); United States v. Menasche, 348 U.S. 528, 538-539 (1955) ("It is our duty to give effect, if possible, to every clause and word of a statute." (internal quotation marks omitted); NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1, 30 (1937) ("The cardinal principle of statutory construction is to save and not to destroy. We have repeatedly held that as between two possible interpretations of a statute, by one of which it would be unconstitutional and by the other valid, our plain duty is to adopt that which will save the act. Even to avoid a serious doubt the rule is the same.").

- Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 842-43 (1984).

- 42 CFR 34.2(b)

- http://www.uscis.gov/files/form/i-601instr.pdf

- INA section 212(a)(1)(A)(iii)

- INA section 212(a)(9)(B)(ii)

- INA Section 212(a)(6)(C)(i)

- http://www.uscis.gov/files/form/I-212instr.pdf

- INA section 212(a)(9)(C)(II)

- Buss, David; Hryck, David; Granwell, Alan (August 2007). "The U.S. Tax Consequences of Expatriation: Is It a Tax Planning Opportunity or a Trap for the Unwary?" (PDF). International Tax Strategies. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- "9 FAM 40.105: Notes". Foreign Affairs Manual (PDF). U.S. Department of State. 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- INA Section 212(a)(9)(C)(i)(I)

- 8 CFR 212.7(d); Meija v. Gonzales, 499 F.3d 991 (9th Cir. 2007); Samuels v. Chertoff, 550 F.3d 252 (2nd Cir. 2008)

- See also INA section 212(a)(1)(A)(iii).

- INA section 212(a)(3)(D)(iv)

- INA section 212(a)(6)(E)(i)

- 8 C.F.R. 1003.2(c)(1) ("A motion to reopen proceedings for the purpose of submitting an application for relief must be accompanied by the appropriate application for relief and all supporting documentation. . . .").