Zov Tigra National Park

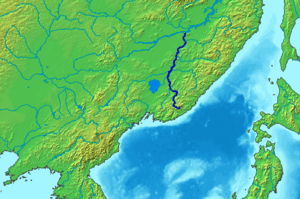

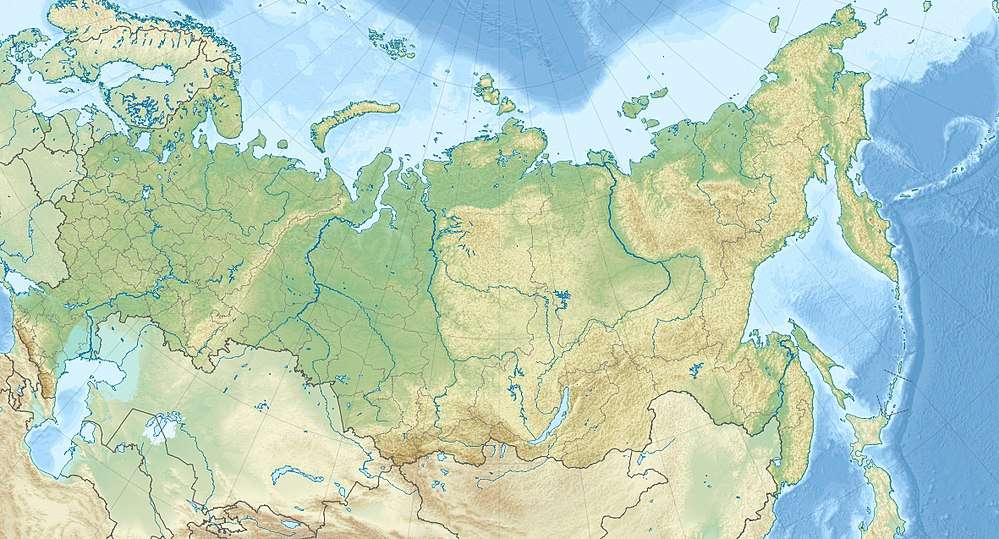

Zov Tigra National Park (Russian: Зов Тигра национальный парк Zov Tigra natsionalnyy park), (in English, "Call of the Tiger National Park", or "Roar of the Tiger") is a mountainous refuge for the endangered Amur Tiger. The park encompasses an area of 83,384 hectares (206,046 acres; 834 km2; 322 sq mi) on the southeast coast of Russia's Far East in the federal district Primorsky Krai (in English, "Maritime Region"). The park is about 100 km northeast of Vladivostok, on both the eastern and western slopes of the southern Sikhote-Alin mountain range, a range that runs north-south through the Primorsky Krai. The relatively warm waters of the Sea of Japan are to the east, the Korean peninsula to the south, and China to the West. The terrain in rugged and difficult to access, with heavily forested taiga coexisting with tropical species of animals and birds.[1] The park is relatively isolated from human development, and functions as a conservation reserve. Tourists may visit the portions of the park marked for recreation, but entry to the protected zones is only possible in the company of park rangers.

| Zov Tigra National Park | |

|---|---|

| "Roar of the Tiger" National Park Russian: Зов Тигра национальный парк | |

IUCN category II (national park) | |

Sikhote-Aline Range in Zov Tigra ("Call of the Tiger") National Park | |

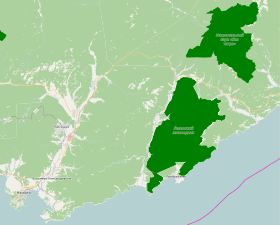

Location of Park | |

| Location | Lazovsky District of Primorsky Krai |

| Nearest city | Vladivostok |

| Coordinates | 43°35′N 134°16′E |

| Established | June 2, 2007 |

| Governing body | FGBI "Joint Directorate of Lazovsky Nature Reserve and National Park |

| Website | http://zov-tigra.lazovzap.ru/ |

Topography

The southern end of the Primorsky maritime province was not glaciated in the most recent ice age, creating conditions for high levels of biodiversity. Zov Tigra occupies the highlands at the southern end of the region, on the ridge of the Sikhote-Alin mountains. The Milogradovik River flows from the area south to the Sea of Japan, some 50 miles to the south. Flowing to the north, tributaries of the Ussuri River make their way to the Amur River basin. These rivers drop quickly in narrow canyons with rapids known for sudden floods in the Spring rainy season.

The mountains are rugged and isolated. Only a few former logging roads approach the park, and access is difficult even during the summer. The park's website notes that a logging road that appears on maps to the north is in fact often not passable, even with off-road vehicles. The mountains are medium in height, with the highest point being Mt. Cloud at 1,854 meters above sea level, and the lowest point in the river valley of 155 meters. There are 56 peaks over 1,000 meters in height.[1] On the upper Ussuri/Milogradovka is a large peatland measuring 4–6 km by 1.5–2 km (Yaklanov, p. 10),[2] Primorye's highest bog.[3]

Climate

The climate of Zov Tigra is Humid continental, warm summer subtype Humid Continental (Koppen classification Dwb). This climate is characterized by large daily and annual swings in temperature, and precipitation spread throughout the year with snow in winter.[4][5] The average temperature is -17 degrees (C) in the Winter and warms to 30 C in the July August. The northern part of the park, which includes the beginnings of the Ussuri River) is significantly colder than the southern part - 0.4 degrees (C) on average, versus the milder 2.4 degree (C) of the south. The northern sections also have less annual precipitation (539 mm) than the south (764 mm). On forested slopes, the typical snowfall in Winter is about 50 cm.[1]

Autumn in the region is clear, warm, dry and with gradually declining temperatures. This has been called the "golden Far East Autumn."[6]

Ecoregion

Zov Tigra is in the Ussuri broadleaf and mixed forests ecoregion, which covers mountainous areas above the lower Amur River and Ussuri River.[7] Such ecoregions are characterized by wide daily and annual variations in temperature, and a forest cover.[8]

The park is situated in a way that maximizes plant and animal diversity. It is at multiple meeting points: the meeting of continental and maritime zones (Eurasia and the Pacific Ocean) and the meeting of hot and cold-loving species from both temperate and sub-tropic zones (being on the 45 degree latitude line, the park is halfway between the North and South Pole). It is also a geological contact region between ancient (Achean-Proterozoic) stable base rocks to the west, and more active tectonic formations to the east in the Sea of Japan. Furthermore, it is on major migration routes of birds and other animals, and has a topography that escaped both recent glaciation and human development.[2]

The resulting diversity of habitats and isolation gives the Primorsky region the highest levels of biodiversity in Russia.

Plants

Elevation differentials between mountain peak and valley floor can exceed 1,200 meters, displaying zones of vegetation based altitude. The lowest zone, below 600 meters in the valleys and lower slopes, is a mixed forest of coniferous and broad-leafed trees. In the southern, milder areas of the park are belts of oak forest, and associated vegetation, that shows the effects of former selective logging (foot-based) and forest fires. There are no oaks in the northern, colder reaches. From 600 meters to 1100 meters is a belt of fir-spruce forests, with the trees often covered with coniferous epiphytic mosses and lichens. Above 1100 meters is a zone of subalpine shrubs and firs.[2] A zone of alpine meadows and flowers leads to bare areas at the highest peaks.[1]

Aside from these main zones, there are smaller groups of plant communities, including stands of larch forest where pine-spruce or cedar-broadleaf stands have been cleared by fire or past logging; these temporary larch communities will be succeeded by pine-deciduous and pine-spruce.

Mongolian oak in June and October

Mongolian oak in June and October- Highland areas of Zov Tigra are rugged.

In addition to the altitude zones, at any given spot the temperate forests typically have four levels above ground: a canopy of the dominant species of tree, a slightly lower layer of mature trees, a shrub layer, and an understory of grasses.[2]

Over 2,500 different species of plants have been recorded in the Primorsky region, with many of them found in Zov Tigra. In the Red Book of rare and vulnerable species of the Primorsky region, there are 343 species of vulnerable plants and 55 species of fungi.

Animals

Zov tigra was established in part to act as a "source habitat" for the recovery of the Amur Tiger and its prey base. A survey in 2012 identified four Amur tigers resident in the park, and four more visiting the protected areas frequently. The base of prey (mostly ungulates) was steady, with a census of over 1,200 Manchurian deer, 800 Roe deer, and 99 Sika deer and 189 wild boars.[9] These species make up some 85% of the Amur tiger's diet. Tigers are known as an "umbrella species" for conservation: their success in a region indicates that the species below them are in a healthy balance.[10]

- Amur Tiger

- Manchurian Deer

Far Eastern Forest Cat

Far Eastern Forest Cat

Brown bears are common in area; with a density estimated by the park administration as 0.4-0.5 per 10 km2. Lynx are found at approximately the same density. The Far Eastern Forest Cat is found in the broad-leaf and oak valleys. The critically endangered Amur Leopard has not been resident since the 1970s, but there are hopes that the growing protection level of Zov Tigra will support a return.[1]

The three main threats to the animals of Zov Tigra are poaching, forest fires, and (historically) logging. Park management, working with conservation organizations, have stepped up anti-poaching patrols and enforcement.

History

There are many archaeological sites of fortified towns and villages near the border of the park, dating to the 12th-century Jurchen Empire. These sites have not been systematically investigated.

In 2014, the administration of Zov Tigra National Park was consolidated with the 120,000 hectare Lazovsky Nature Reserve to the south. The Lazovsky Reserve extends protected coverage to the south, and is also a known habitat for Amur tigers. (There is a small area between the two that is managed by a private hunting club).[11]

Tourism

To visit the park, you must submit an application in advance. Tours of the main sights are conducted in the presence of park rangers. There are fees for services such as transportation in the park, guides, and use of guest quarters or campsites.[12]

The park is primarily oriented towards the protection of vulnerable species. The areas open to recreation tend to be narrow corridors to the main attractions, such as waterfalls and mountain peaks, but are still difficult to reach and not well developed with facilities. In 2015, due to forest fire danger, the park was temporarily closed to citizens.[13]

See also

- Protected areas of Russia

- Amur tiger

- Primorsky region

References

- "Call of the Tiger Park, Official Park Web Site". MNRE of the Russian Federation.

- P Ya Yaklanov, Managing Editor, and Belyaev EA, Bersenev YI,, Kachur AP, Curley L. Klyuyev PA, skating ALO, Kryukov VH, Pannchev AM, Romanov MT, Skrylnikov TP, Sleptsov IY, Stepanko, AA Tiunov MP, Harlamenco,PO Sharov, Shokhrin EP. "Monograph: Zov Tigra National Park," (PDF). Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology of the Russian Federation.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- A. Panichev. "CENTRAL SIKHOTE ALIN ON THE BALANCE OF ECOLOGICAL AND ECONOMIC POLICY". Pacific Institute of Geography, Far East Sciences Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Kottek, M., J. Grieser, C. Beck, B. Rudolf, and F. Rubel, 2006. "World Map of Koppen-Geiger Climate Classification Updated" (PDF). Gebrüder Borntraeger 2006. Retrieved September 14, 2019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Dataset - Koppen climate classifications". World Bank. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "Primorsky Region". Phoenix Fund.

- "Terrestrial Ecoregions". World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

- "Map of Ecoregions 2017". Resolve, using WWF data. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "Amur Tiger Conservation in Zov Tigra National Park in 2012, Russian Far East" (PDF). Phoenix Fund. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Howard Youth. "Russia's Tough Tigers". The Smithsonian Insititution. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- "Amur Leopard and Tiger Alliance, Annual Report 2013" (PDF). Amur Leopard and Tiger Alliance (ALTA). Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- "Our Services". Zov Tigra Park Website. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- "In connection with the onset of autumn fire season and the threat of forest fires NNA National Park PROHIBITED citizens visiting the national park, "Call of the Tiger" from October 28, 2015, until further notice". Zov Tigra Park Website. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

External links

- Amur Information Center, Zov Tigra National Park, Photo Gallery

- Primorye, Russia's Maritime Province, Portal. Far East Geological Laboratory

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zov Tigra National Park. |