Zinapécuaro

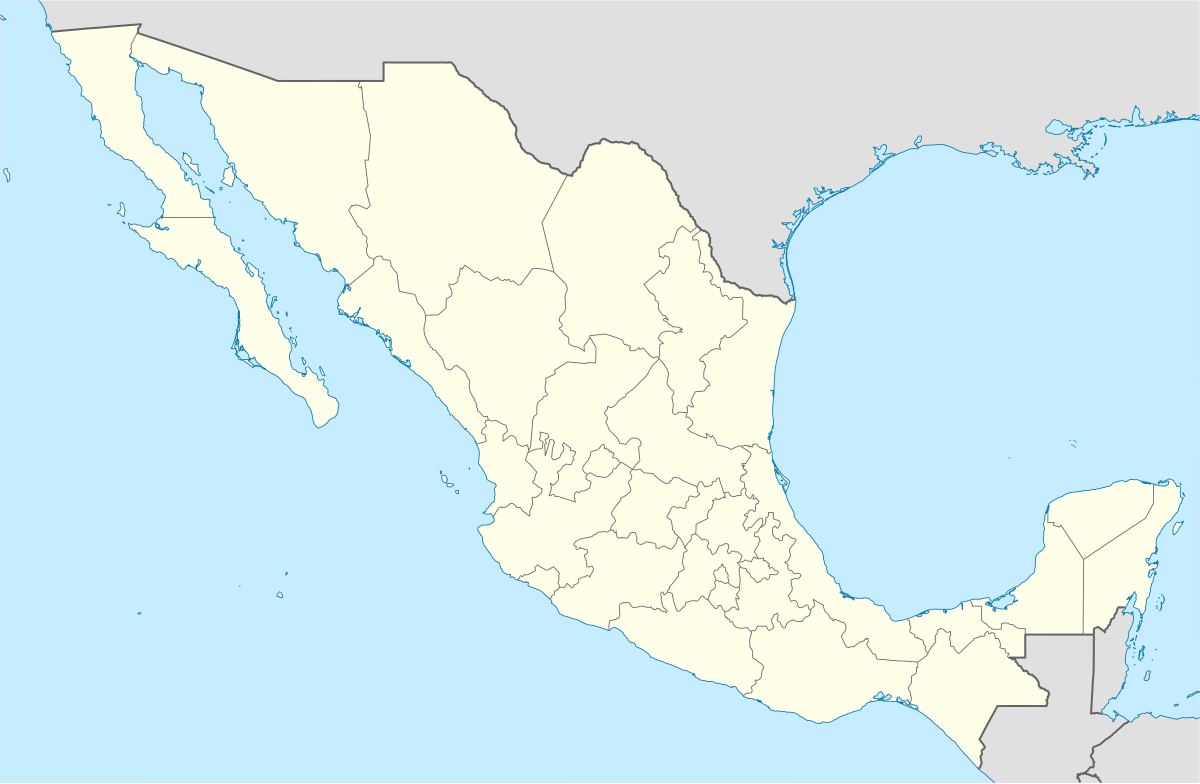

Zinapécuaro is a municipality in the Mexican state of Michoacán, located 50 kilometres (31 mi) northeast of the state capital Morelia.[2]

Zinapécuaro | |

|---|---|

Hidalgo Theatre in Zinapécuaro de Figueroa | |

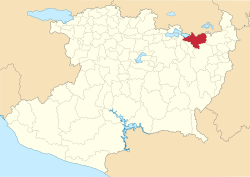

Location in Michoacán | |

Zinapécuaro Location in Mexico | |

| Coordinates: 19°51′31″N 100°49′38″W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Established | 15 March 1825 |

| Seat | Zinapécuaro de Figueroa |

| Government | |

| • President | María del Refugio Silva Durán |

| Area | |

| • Total | 598.179 km2 (230.958 sq mi) |

| Elevation [1] (of seat) | 1,887 m (6,191 ft) |

| Population (2010 Census)[3] | |

| • Total | 46,666 |

| • Estimate (2015 Intercensal Survey)[4] | 47,327 |

| • Density | 78/km2 (200/sq mi) |

| • Seat | 15,875 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (Central) |

| Postal codes | 58930–58967 |

| Area code | 451 |

| Website | Official website |

Geography

The municipality of Zinapécuaro is located in northeast Michoacán on the border with Guanajuato. In Michoacán it borders the municipalities of Álvaro Obregón to the west, Indaparapeo and Queréndaro to the southwest, Hidalgo to the southeast, and Maravatío to the east. To the north it borders the municipality of Acámbaro in Guanajuato.[3] Zinapécuaro covers an area of 598.179 square kilometres (230.958 sq mi) and comprises 1.0% of the state's area.[4]

The flat western part of the municipality lies in the Lake Cuitzeo basin. Along the basin's eastern edge are a series of hills and ridges where the municipal seat is located. The Ucareo Valley in the eastern part of the municipality comprises part of an ancient caldera, and is over 700 metres (2,300 ft) higher in elevation than Lake Cuitzeo. It is an agricultural area flanked by forested hills and ridges.[5][6]

Zinapécuaro's climate is temperate with summer rains.[2] Average annual precipitation in the municipality ranges between 700 and 1600 millimetres.[6]

| Climate data for Zinapécuaro weather station (1981–2010 averages, 1951–2010 extremes) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.0 (86.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

37.8 (100.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.0 (98.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

30.0 (86.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24.4 (75.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.9 (82.2) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.2 (84.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.7 (76.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.9 (58.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.4 (70.5) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.1 (55.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.0 (24.8) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.7 (42.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 19.1 (0.75) |

12.2 (0.48) |

4.9 (0.19) |

8.8 (0.35) |

42.1 (1.66) |

127.0 (5.00) |

216.3 (8.52) |

233.1 (9.18) |

153.2 (6.03) |

56.8 (2.24) |

14.5 (0.57) |

4.3 (0.17) |

892.3 (35.13) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 5.8 | 14.9 | 21.4 | 20.6 | 15.7 | 7.5 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 95.4 |

| Source: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional[7][8] | |||||||||||||

History

Two Purépecha words have been suggested as possible sources of the place name Zinapécuaro: tzinapo "obsidian" or tzinápecua "healing".[9] The obsidian quarries near Ucareo include one of the largest known pre-Hispanic quarries in Mesoamerica and were already exploited in the early Formative period. In the late Classic period Ucareo was the principal source of obsidian at Tula and Xochicalco, and Ucareo obsidian was distributed throughout central Mexico, Oaxaca and the northern Yucatán, being found as far away as Chichen Itza.[5] In the Postclassic period the area was controlled by the Tarascans, who built a temple there to worship Cuerauáperi, the mother goddess of Purépecha mythology.[2]

Around 1530, a Spanish settlement was founded at Zinapécuaro by the conquistador Don Luis Montañez.[2] Zinapécuaro was first incorporated on 15 March 1825 as a partido in the department of Oriente in Michoacán. It became a free municipality on 5 February 1918.[10]

Administration

The municipal government comprises a president, a councillor (Spanish: síndico), and ten trustees (regidores), six elected by relative majority and four by proportional representation. The current president of the municipality is Alejandro Correa.[2]

Demographics

In the 2010 Mexican Census, the municipality of Zinapécuaro recorded a population of 46,666 inhabitants living in 11,608 households.[11] It recorded a population of 47,327 inhabitants in the 2015 Intercensal Survey.[4]

There are 97 localities in the municipality,[1] four of which are classified as urban:

- Zinapécuaro de Figueroa, the seat of the municipality located in its west-central part, which recorded a population of 15,875 inhabitants in the 2010 Census;

- Jeráhuaro, a town located 30 kilometres (19 mi) east of the municipal seat in the Ucareo Valley, which had 2822 inhabitants in 2010;

- Ucareo, a town located 27 kilometres (17 mi) east of the municipal seat, which had 2284 inhabitants in 2010;

- Bocaneo, a town located 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) south of the municipal seat, which had 2082 inhabitants in 2010.[11][2]

Economy

Zinapécuaro's economy is largely dependent on foreign remittances.[12][13] Fruit is produced in the area around Jeráhuaro and Ucareo in the eastern part of the municipality.[2]

References

- "Sistema Nacional de Información Municipal" (in Spanish). SEGOB. 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Zinapécuaro". Enciclopedia de los Municipios y Delegaciones de México (in Spanish). INAFED. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Zinapécuaro: Datos generales". Cédulas de información municipal (in Spanish). SEDESOL. 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Panorama sociodemográfico de Michoacán de Ocampo 2015" (PDF) (in Spanish). INEGI. 2016. p. 236. ISBN 978-607-739-850-9. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Healan, Dan M. (1997). "Pre-Hispanic Quarrying in the Ucareo-Zinapecuaro Obsidian Source Area". Ancient Mesoamerica. 8 (1): 77–100. doi:10.1017/S0956536100001590.

- "Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010: Zinapécuaro, Michoacán de Ocampo" (in Spanish). INEGI. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "NORMALES CLIMATOLÓGICAS" (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "NORMALES CLIMATOLÓGICAS" (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Toponimia" (in Spanish). Government of Zinapécuaro. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Estado de Michoacán de Ocampo. División Territorial de 1810 a 1995 (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico: INEGI. 1996. pp. 59, 232–233. ISBN 970-13-1501-4.

- "Resumen municipal: Municipio de Zinapécuaro". Catálogo de Localidades (in Spanish). SEDESOL. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Paz, Fátima (11 November 2014). "70% de la economía de Zinapécuaro depende del envío de remesas familiares: alcalde". Cambio de Michoacán (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Beauregard, Luis Pablo (15 November 2016). "México teme por el futuro de sus remesas tras el triunfo de Trump". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 February 2018.