Zimbabwe Defence Industries

Zimbabwe Defence Industries (Pvt) Ltd (ZDI) is a state-owned Zimbabwean arms manufacturing and procurement company headquartered in Harare, with a primary focus on sporting and military ammunition.[1] In the past it has also manufactured mortar rounds, land mines, and light armoured fighting vehicles such as the Gazelle FRV. During the late 1990s, ZDI was involved in brokering major arms deals between China and other African governments such as the Republic of the Congo.[2] The subsequent economic depression in Zimbabwe, as well as the collapse of the Zimbabwean dollar against major world currencies, have forced ZDI to limit its activity to exporting second-hand equipment from the Zimbabwe Defence Forces.[1] In 2014, the firm was said to be nearly bankrupt.[3]

| Public (state-owned enterprise) | |

| Industry | Arms industry |

| Predecessor | Zimbabwe Arms Manufacturing Corporation (Pty) Ltd |

| Founded | 1984 |

| Headquarters | , |

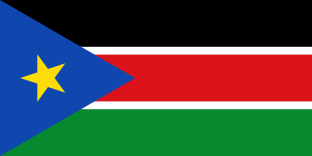

Area served | Sub-Saharan Africa |

Key people |

|

| Products | Firearms, ammunition |

History

Rhodesian arms industry

Prior to Rhodesia's internationally recognised independence as Zimbabwe in 1980, an arms embargo imposed by the United Nations limited the nation's ability to modernise its arsenal. As part of a general import substitution programme initiated during the Rhodesian Bush War, commercial vehicles were converted for military uses and several types of light ammunition manufactured.[4] Small arms such as the Kommando LDP and the Rhogun submachine guns were also produced, although primarily for civilians; most Rhodesian weaponry was designed with those unaccustomed to handling firearms in mind.[5] The local industry remained dependent on South African technical assistance to promote the export of its products and facilitate general distribution. Individual weapons were assembled by joint efforts between civilian engineers and companies that processed the raw metals. Rhodesian security forces occasionally cooperated with their South African counterparts to design equipment which could later be produced in South Africa and imported in violation of the embargo.[5]

By June 1978, Rhodesia had formed an Arms Manufacturing Corporation—based on South Africa's ARMSCOR—intended to manufacture weapons of a general nature. This corporation is believed to have manufactured copies of the Uzi in Salisbury (Harare).[5]

Formation of ZDI

Following the integration of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, weapons and ammunition shortages remained acute. Serious logistical difficulties arose from the parallel employment of Western and Soviet weaponry, which were of different gauges and calibres, often within the same battalion.[6] In August 1981, a sabotage action most likely carried out by South African Special Forces or disgruntled Rhodesian servicemen destroyed most of Zimbabwe's ammunition stocks.[6] Plans for future procurement were put on hold as the National Army (ZNA) was still demobilising troops and remained uncertain of future manpower levels or the amount of funding available for a replacement inventory. Nevertheless, senior officers in the ZNA took this opportunity to lobby for the acquisition of more weapons from domestic suppliers.[6]

Zimbabwe's intervention in the Mozambican Civil War, which culminated in the deployment of 1,000 troops into Tete Province towards the end of 1982, finally provided the impetuous for the establishment of ZDI. A state parastatal which could procure arms in a direct manner while circumventing the army's cumbersome tender process was perceived as necessary for the war effort.[7] Colonel Ian Stansfield, former Quartermaster-General and chief of the ZNA's Procurement Office, was appointed to lead the new effort.[8] Stansfield aimed to build on the once-vibrant defence industry generated by the Rhodesian Bush War. He thus contracted with the separate firms that had once manufactured armoured vehicles, munitions, and small arms during that conflict and offered them an inroad into the export market under the auspices of a united Zimbabwe Defence Industries.[8]

Rhodesian technicians had once suggested that the local production of ammunition for heavy weapons could be possible, although the absence of funds and the embargo had precluded their acquisition of the associated machinery and tooling equipment.[5] At its peak ZDI had finally achieved this goal; the company was able to manufacture mortar bombs for the ZNA's 60mm, 81mm, and 120mm mortar systems, in addition to both 7.62×51mm NATO and 7.62×39mm rounds for Western as well as Soviet rifles and machine guns.[9] During the 1980s it also marketed the Gazelle FRV, an armoured reconnaissance vehicle inspired by the Buffel, without success.[8]

Sanctions and diversification

ZDI's small arms ammunition output, once mostly exported to professional hunters in the United States, decreased considerably following Executive Order 13391 issued by President George W. Bush on 25 November 2005.[1] This added ZDI to an American sanctions list that included Zimbabwean leader Robert Mugabe and other key figures of the ruling ZANU-PF party, who were accused of violating human rights. The controversy over supplying arms to Zimbabwe has persisted as late as 2008, when South African trade unionists blocked the unloading of Chinese arms in Durban bound for Harare.[10] ZDI arranged to have the cargo rerouted, possibly through Angola, a fact insinuated to a United Nations arms consultant when he visited its Harare facilities later that June.[10]

In 2001, ZDI formed a Congolese subsidiary in conjunction with the Kinshasha-based Strategic Reserves, Congo-Duka, which is believed to oversee the illicit transfer of arms to Zimbabwe.[10] Military officials in the Democratic Republic of the Congo's procurement office have been accused of using real end-user certificates in a fraudulent manner to acquire weaponry for Congo-Duka or ZDI.[10]

During the ill-fated 2004 Equatorial Guinea coup d'état attempt, ZDI sparked controversy when it emerged that Managing Director Tshinga Dube had committed to sell a massive consignment of AK-47s, RPG-7s, PKM machine guns, and over 45,000 rounds of ammunition to British and South African mercenaries under Simon Mann.[11] Zimbabwean authorities later arrested Mann and claimed the sale had been approved as part of an elaborate sting operation. Nevertheless, the initial ease with which Mann had been able to negotiate the purchase without a licensed dealer or an end-user certificate aroused suspicion among South African investigators carrying out their own inquiry, condemning ZDI for its apparent carelessness.[12]

Zimbabwean arms exports continued to fall throughout the 2000s, with only minor sales being made to the Lord's Resistance Army, Interahamwe, and Sri Lanka.[1] This has been attributed to the relatively high cost of manufacturing in Zimbabwe, which in turn necessitates higher market prices. Consequently, ZDI-made arms and ammunition have been unable to compete with the cheaper identical products being offered by countries such as China abroad. The inflated civil service wage—which applies to ZDI workers—has also been identified as another factor slowing down output.[9] Between 2004 and 2014 Managing Director Dube presided over a methodical diversification process in an attempt to drum up revenue. In January 2005, ZDI announced its intention to take advantage of the ongoing land reform programme by managing expropriated commercial farmland on behalf of the army.[13] The company garnered headlines when it attempted to seize the farm of Roy Bennett, a white Zimbabwean member of parliament.[13] ZDI currently manages at least one farm, although others it has occupied remain neglected.[13] ZDI's next major diversification phase was in the Marange diamond fields, where it haggled the majority shares in Anjin Investments, a joint mining project between Zimbabwe and China.[3]

In May 2014, ZDI began buying and selling scrap metal from two other parastatals, Ziscosteel and Zimbabwe National Railways. This venture collapsed when it emerged that the company had failed to secure the relevant permits from the Ministry of Mines and Development.[9] A second diversification attempt, aimed at supplying food for the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, also ended abruptly when the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority accused ZDI of importing its rations without paying duties.[9] Both the Zimbabwe National Army and Zimbabwe Republic Police also defaulted on payments for ammunition due to lack of funds, and it was widely reported that ZDI could no longer pay its workers. Employees claimed they had not received their wages for seven months.[3] In response, the company sent most of its staff on forced leave.[9]

Facilities

Zimbabwe Defence Industries operates a facility in Domboshawa, known as Elphida, where it manufactures arms and munitions.[13] It is also said to own a mortar shell plant, where 155mm artillery shells, rocket launchers and hand grenades were once produced.[9] Since 2008 the main factory operated at a greatly reduced level of productivity, only offering small arms and small arms ammunition.[1] American and European Union sanctions and disinvestment, compounded by an exodus of technically skilled personnel, have badly damaged the ZDI's ability to continue manufacturing.[1] The factory machinery is antiquated and no resources are available to replace or even refurbish it.[9] ZDI still possesses a preexisting stockpile of ammunition but can no longer meet its immediate overhead costs, including raw materials. As of March 2015 Managing Director Dube confirmed that all production lines had been halted.[9]

ZDI owns at least one banana plantation, Valhalla, in Manicaland Province.[13] ZDI employees still reporting to work have complained of being used as forced labour at an unidentified company farm.[3]

Clients

Non-state entities

.svg.png)

Notes and citations

- Citations

- Southern Africa Report, p. 9.

- Demetriou, Muggah & Biddle 2002, p. 11.

- Staff 2014.

- Nelson 1982, p. 255.

- Anti-Apartheid Movement 1979, p. 37.

- Nelson 1982, p. 272.

- Hill, p. 215.

- Locke & Cooke, p. 147.

- Nkala 2015.

- Johnson-Thomas & Danssaert 2009.

- Roberts 2006, p. 151.

- Roberts 2006, p. 152.

- Wasosa 2005.

- Vines 1999, p. 145.

- Howe 2004, p. 98.

- Cock & McKenzie 1998, p. 149.

- Online sources

- Demetriou, Spyros; Muggah, Robert; Biddle, Ian (2002). "Small Arms Availability, Trade and Impacts in the Republic of Congo" (PDF). Geneva: Small Arms Survey. Retrieved 20 December 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson-Thomas, Brian; Danssaert, Peter (July 2009). "Zimbabwe - Arms and Corruption: Fuelling Human Rights Abuses" (PDF). Antwerp: International Peace Information Service. Retrieved 24 February 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Southern Africa Report, (various) (July 2011). "Zimbabwe Security Forces" (PDF). Randburg: Mopani Media. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newspaper and journal articles

- Nkala, Oscar (5 March 2015). "Zimbabwe Defence Industries should be shut down – manager". Nehanda Radio. Harare. Retrieved 24 February 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Staff, Writer (21 March 2014). "Zimbabwe Defence Industries broke". Zimbabwe Independent. Harare. Retrieved 24 February 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wasosa, Munyaradzi (28 January 2005). "ZDI admits involvement in Charleswood seizure". Zimbabwe Independent. Harare. Retrieved 24 February 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bibliography

- Anti-Apartheid Movement, (various) (1979). Fireforce Exposed: Rhodesian Security Forces and Their Role in Defending White Supremacy. London: The Anti-Apartheid Movement. ISBN 978-0900065040.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cock, Jacklyn; Mckenzie, Penny (1998). From Defence to Development: Redirecting Military Resources in South Africa. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre. ISBN 978-0889368538.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, Geoff (2003). The Battle for Zimbabwe: The Final Countdown. Cape Town: Zebra Press. ISBN 978-1868726523.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howe, Herbert (2004). Ambiguous Order: Military Forces in African States. London: Lynne Reinner Publishers. ISBN 978-1588263155.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nelson, Harold D, ed. (1983). Zimbabwe, a Country Study. Area Handbook Series (Second ed.). Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, American University. OCLC 227599708.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Locke, Peter G.; Cooke, Peter D.F. (1995). Fighting vehicles and weapons of Rhodesia, 1965-80. Wellington: P&P Publishing. ISBN 978-0473024130.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberts, Adam (2006). The Wonga Coup: Simon Mann's Plot to Seize Oil Billions in Africa. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1846682346.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vines, Alex (1999). Angola Unravels: The Rise and Fall of the Lusaka Peace Process. New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1564322333.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)